Cricopharyngeal Myotomy (CPM)

Cricopharyngeal myotomy (CPM) is a procedure in which the cricopharyngeus muscle, which makes a “ring” around the upper esophagus, is divided or cut across in order to break its grip. This is done in cases where this cricopharyngeus muscle (i.e., the upper esophageal sphincter) fails to relax when one swallows (antegrade cricopharyngeal dysfunction [A-CPD]), resulting in a functional obstruction. CPM leaves the muscle open all the time, and allows the person to resume swallowing relatively normally.

In a percentage of those with cricopharyngeus muscle non-relaxation, the continual high pressures of swallowing may eventually cause a “hernia” in the swallowing passage called a Zenker’s diverticulum.

CPM Procedure

CPM is accomplished under general anesthesia, in one of two ways: The preferred, newer methodology, is performed endoscopically. Using this method, a hollow, lighted “tube”—called an esophagoscope—is inserted into the throat and upper esophagus to examine the area and plan the next step. Then, a special laser scope is placed in the upper esophagus. A microscope permits a magnified, brightly-lit view of the offending ring of muscle.

The laser is used to divide the muscle and break its “grip.” If a Zenker’s sac is apparent, it is “marsupialized,” which means that its opening is widened in order to be sure the sac doesn’t retain food, but instead empties its contents directly into the esophagus.

Depending upon patient and surgical issues, a suction drain may be placed within the upper esophagus and brought out through the nose. A second small tube for feeding may also be placed through the nose, and down into the stomach. When placed, both tubes are removed the morning following surgery.

If a clear view cannot be achieved during esophagoscopy due to difficult patient anatomy (e.g., jaws won’t open well, small lower jaw, short neck, large upper teeth), then we return to a more traditional approach through an incision on the lower left neck. In this case, the muscle is divided from outside in. Depending on a number of issues, an associated Zenker’s diverticulum may or may not be removed at the same time.

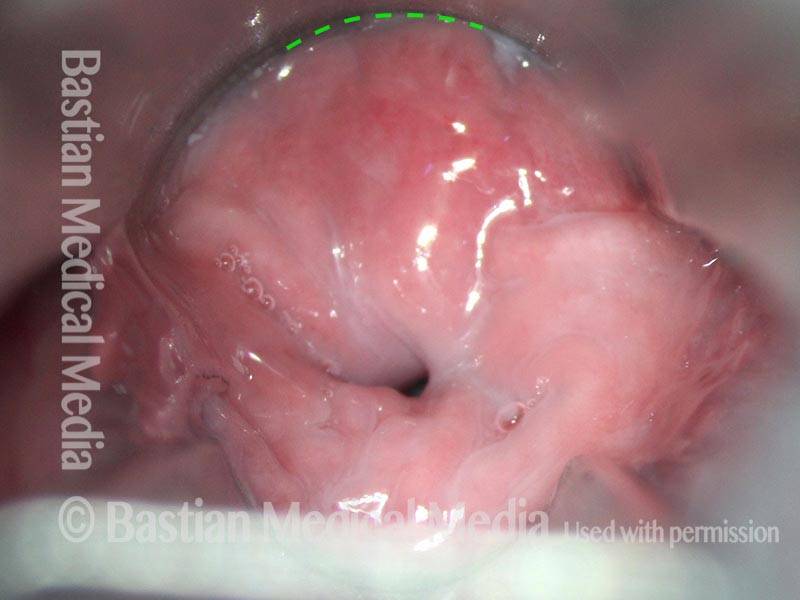

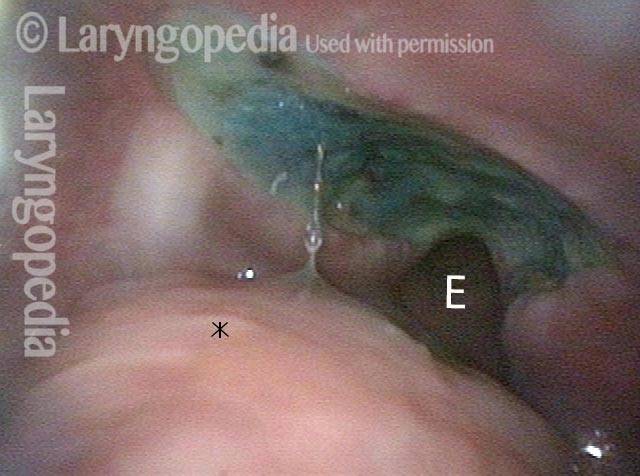

Cricopharyngeal myotomy (1 of 7)

Cricopharyngeal myotomy (1 of 7)

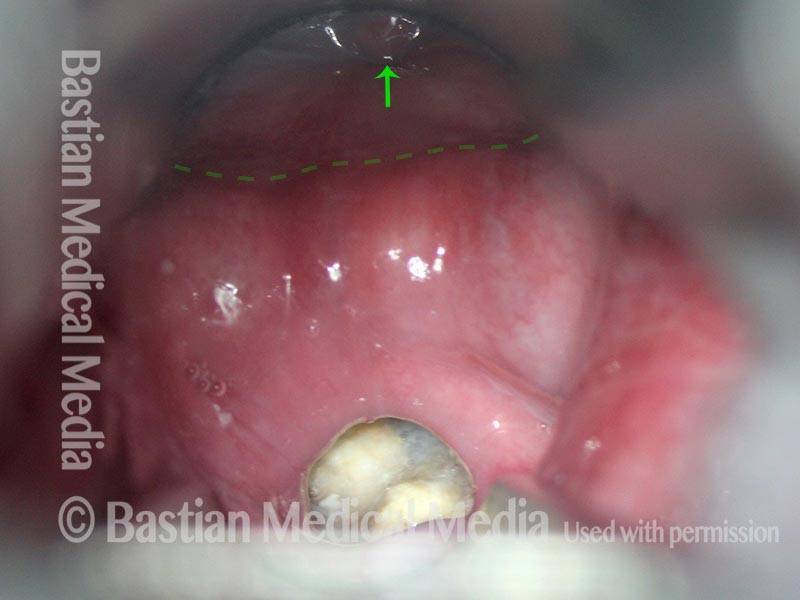

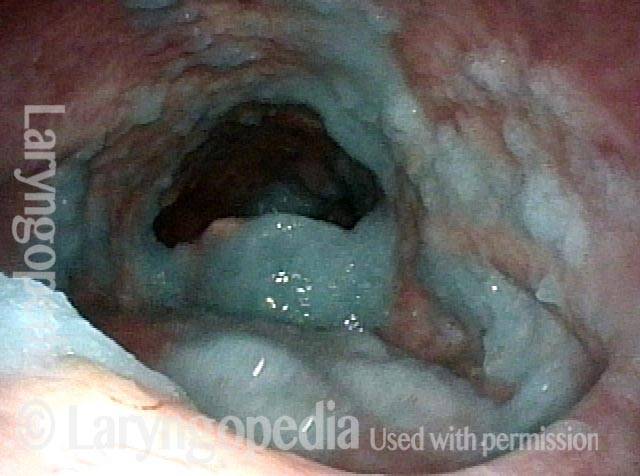

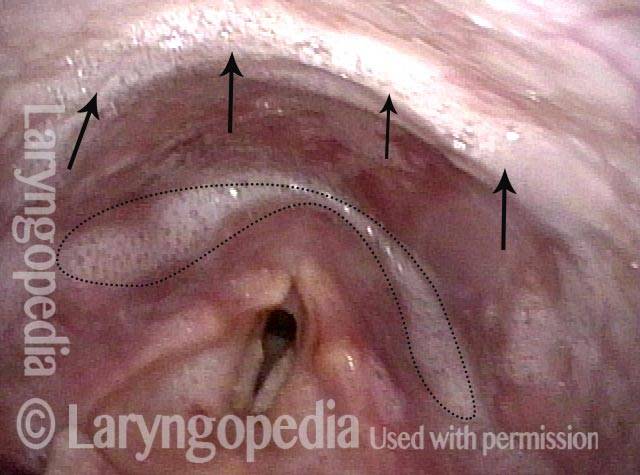

Cricopharyngeal myotomy (2 of 7)

Cricopharyngeal myotomy (2 of 7)

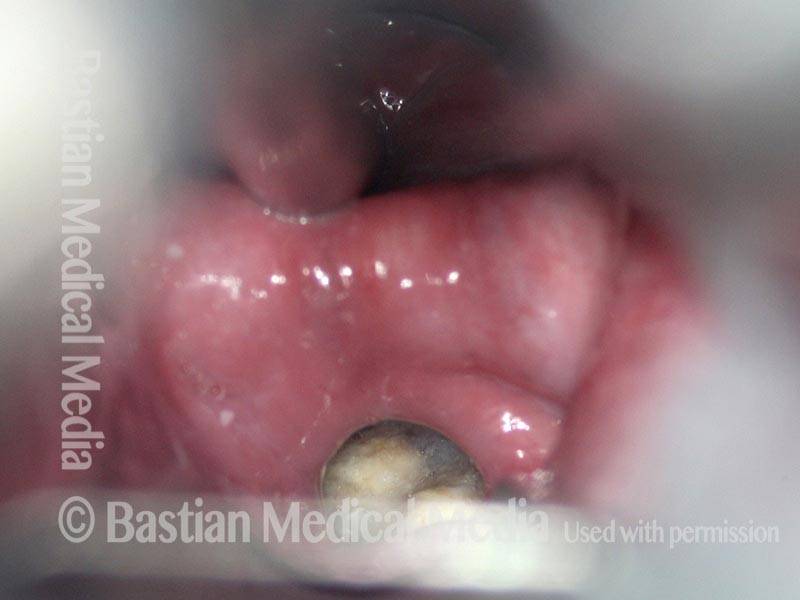

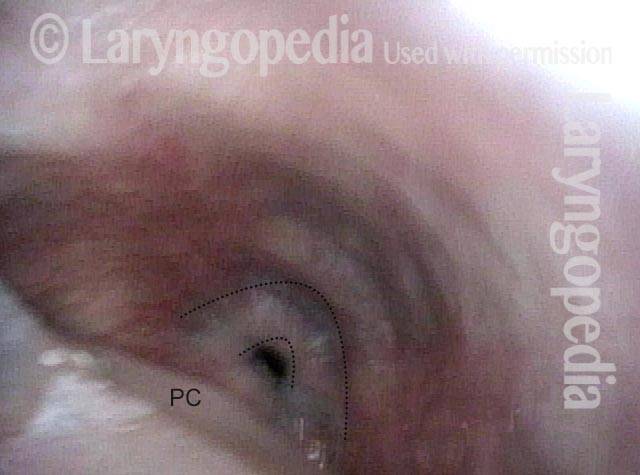

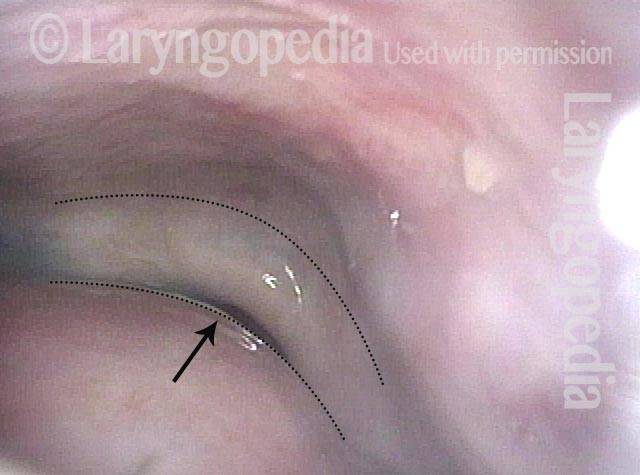

Cricopharyngeal myotomy (3 of 7)

Cricopharyngeal myotomy (3 of 7)

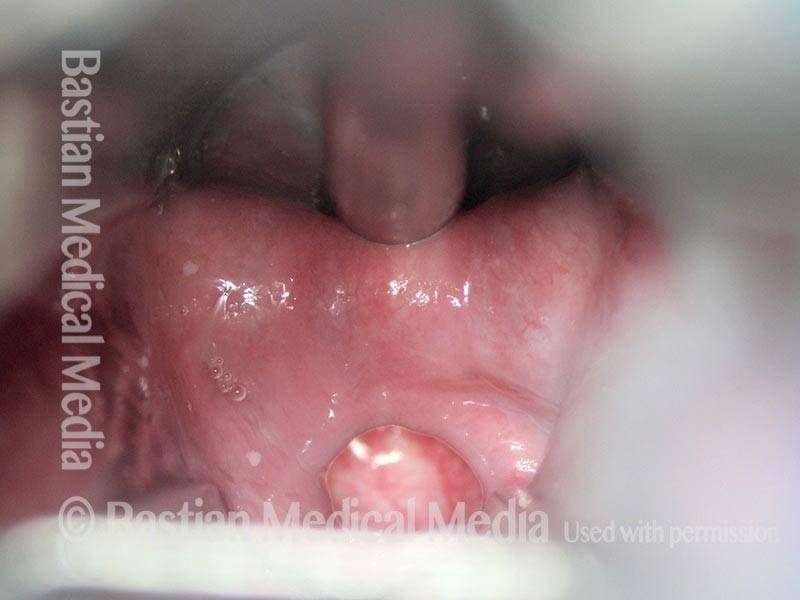

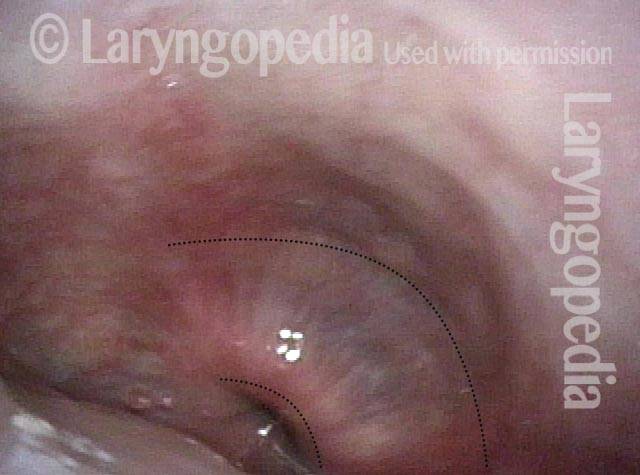

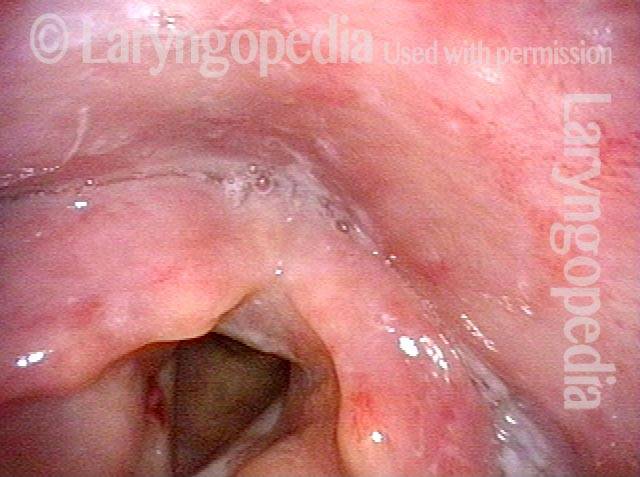

Cricopharyngeal myotomy (4 of 7)

Cricopharyngeal myotomy (4 of 7)

Cricopharyngeal myotomy (5 of 7)

Cricopharyngeal myotomy (5 of 7)

Cricopharyngeal myotomy (6 of 7)

Cricopharyngeal myotomy (6 of 7)

Cricopharyngeal myotomy (7 of 7)

Cricopharyngeal myotomy (7 of 7)

Success rate of CPM

The success rate can vary according to the degree to which the person is an ideal candidate for this surgery. When solid food dysphagia is the main symptom, and when x-ray studies show non-relaxation of the muscle, the procedure can dramatically restore the individual’s ability to swallow.

Patient satisfaction with the results is routinely very high. “I can eat anything I want again,” is frequently-heard after surgery. Once in awhile an individual has more than one swallowing deficit, of which CPMD is only one. In this case, swallowing may be better, but still not perfect after CPM.

Risks of CPM

Unless you have significant health issues, risks added together are very small. Risks may include:

- A drug reaction, heart problem, etc., during general anesthesia.

- Dental trauma—e.g., chipped, scratched, broken, or dislodged tooth.

- If surgery is done within the esophagus there is a small risk of a special, potentially severe infection called mediastinitis. (We’ve not seen this problem with a BVI total of an estimated 120 CPM surgeries).

- If the surgery is done through a neck incision, there is an added small risk of temporary—or rarely, permanent—paralysis of one vocal fold, which is managed in a relatively straightforward manner.

- The final “risk” or outcome is that the doctor cannot guarantee the precise degree of improvement—whether the result will be “good,” “very good,” or “spectacular.” That depends to large degree on the precise components of the original problem; as the doctor tends to know these before surgery, he or she can usually make a reasonably reliable estimate of the expected improvement.

What to expect post-CPM

After surgery, patients return home either later the day of surgery, or the morning after, with rare exception. Of course, a family member or friend must do the driving. Most individuals have minimal anesthesia after-effects. Nausea, for example, has become relatively uncommon.

Pain medication consists of either Tylenol or Tylenol with Codeine, barring allergy or sensitivity. Water may be swallowed immediately after surgery.

The first five days, diet should consist of liquids and very soft foods. Water is always the last thing swallowed after every “meal,” to “rinse out” the area of surgery. Some find that salty or acidic food / liquids will burn the area of surgery.

Occasionally the teeth feel a little sore and loose, especially the upper central incisors.

A-CPD, before, during, and after Myotomy.

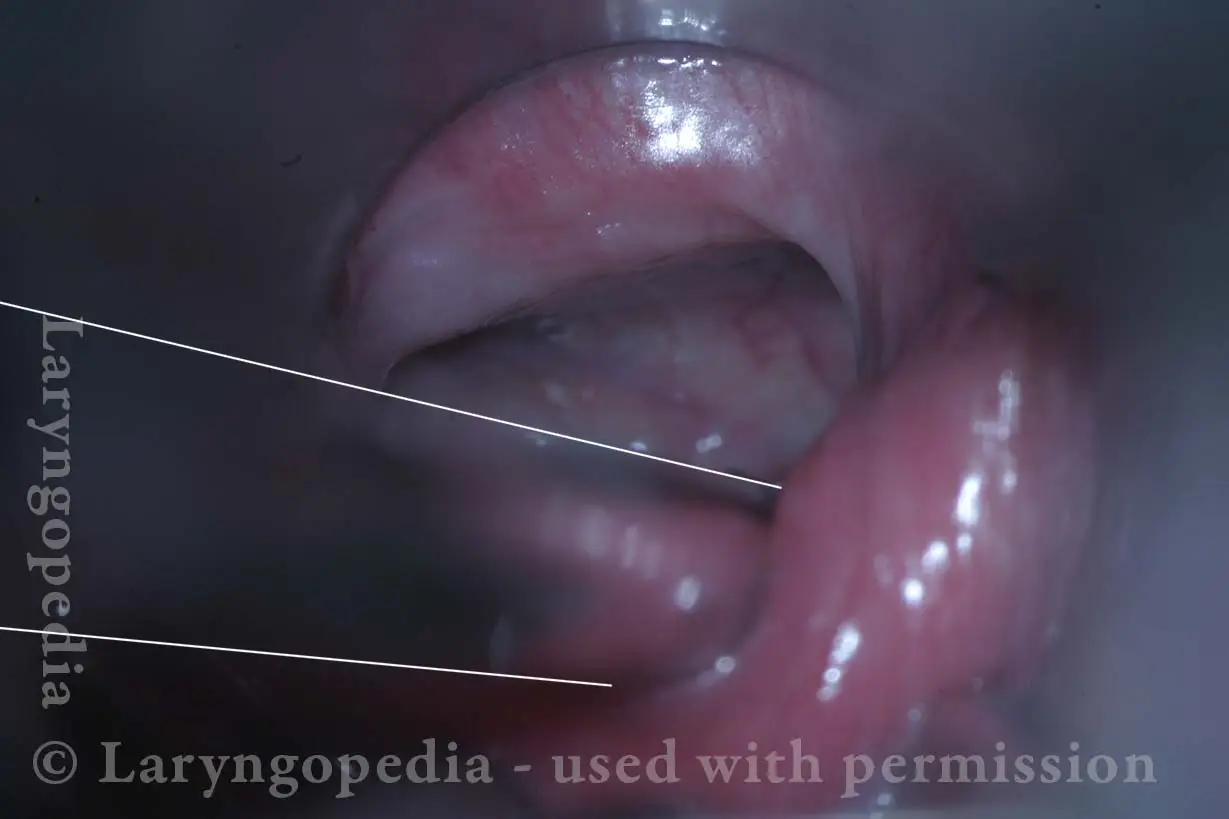

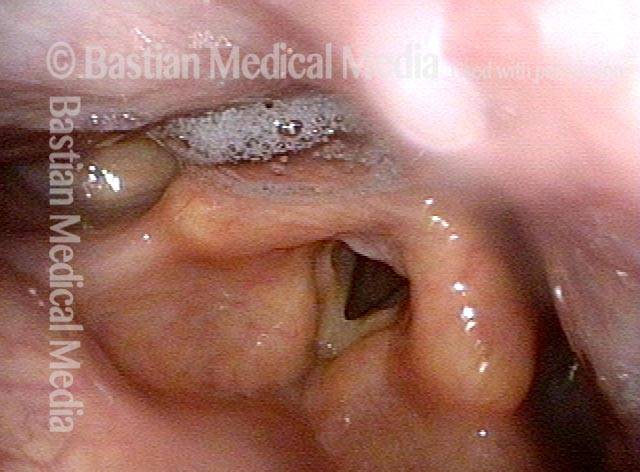

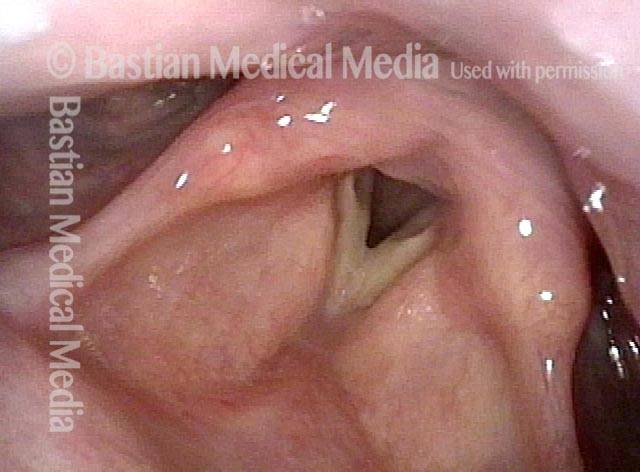

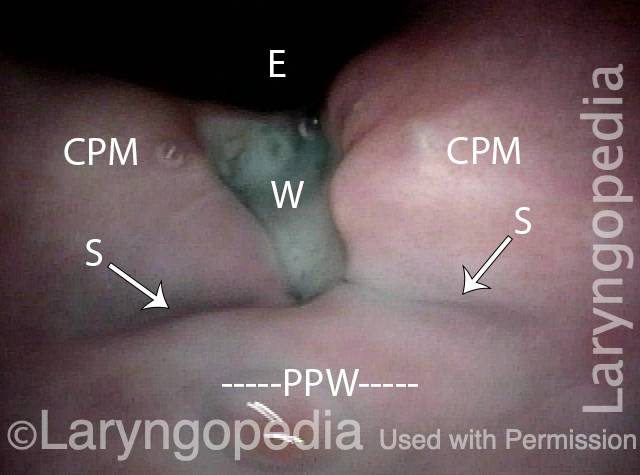

Non-relaxing cricopharyngeus muscle (1 of 4)

Non-relaxing cricopharyngeus muscle (1 of 4)

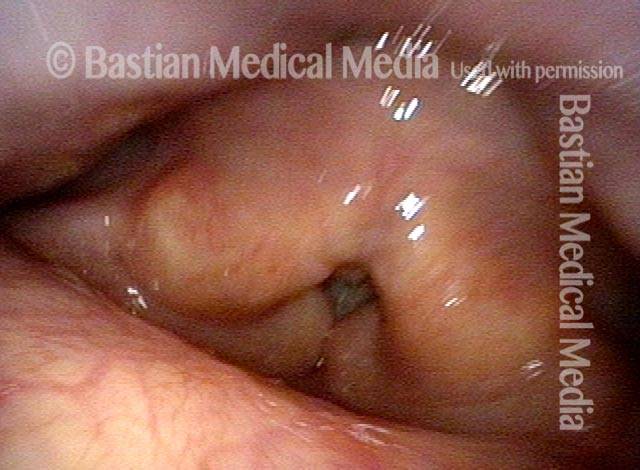

Opening the esophageal orifice (2 of 4)

Opening the esophageal orifice (2 of 4)

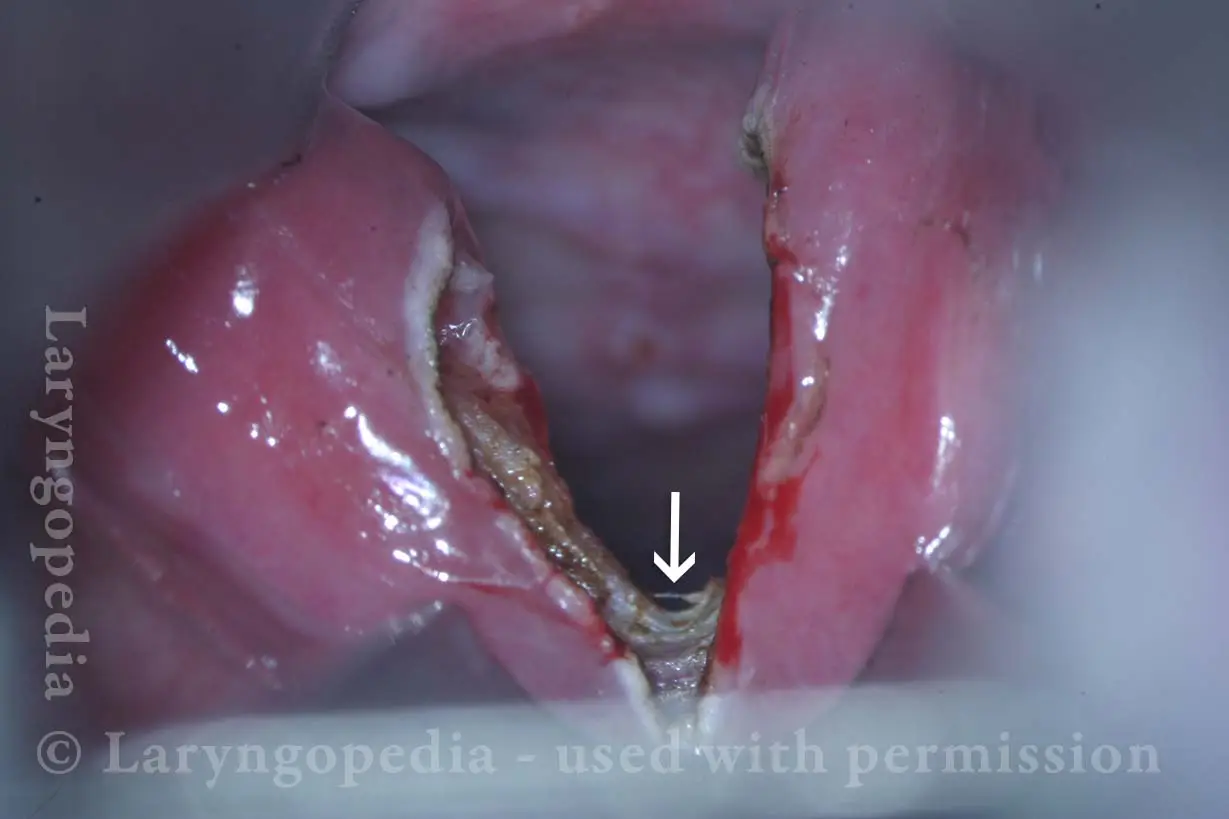

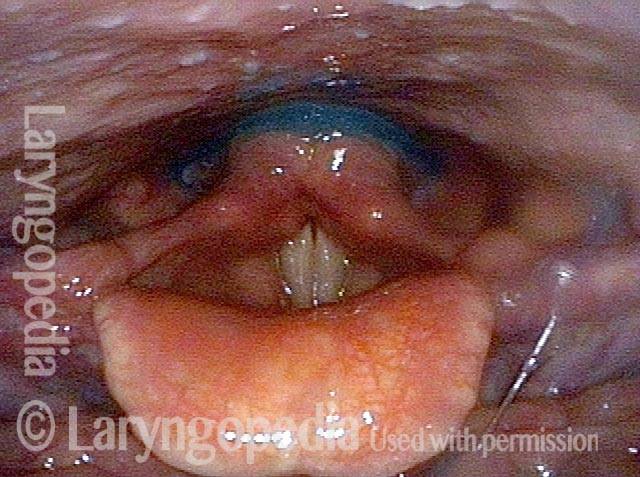

Laser cricopharyngeus myotomy (3 of 4)

Laser cricopharyngeus myotomy (3 of 4)

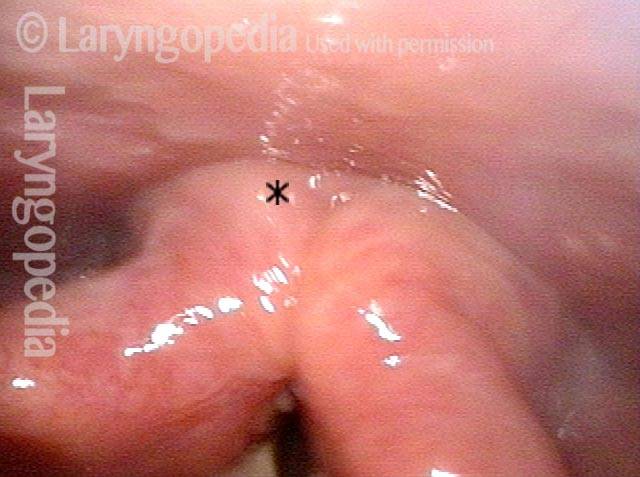

Cricopharyngeus myotomy nearly complete (4 of 4)

Cricopharyngeus myotomy nearly complete (4 of 4)

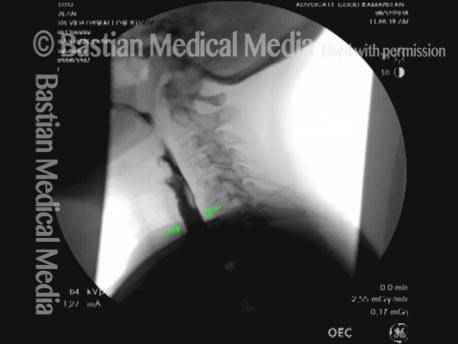

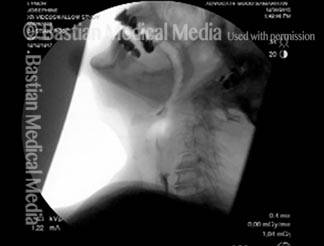

A-CPD X-ray, before and after Myotomy

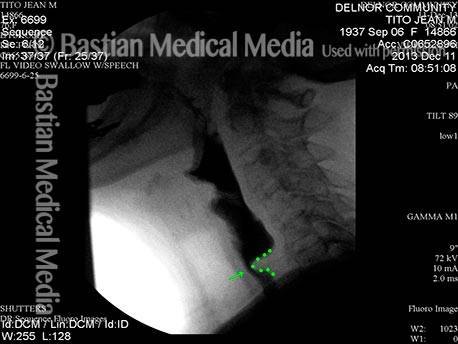

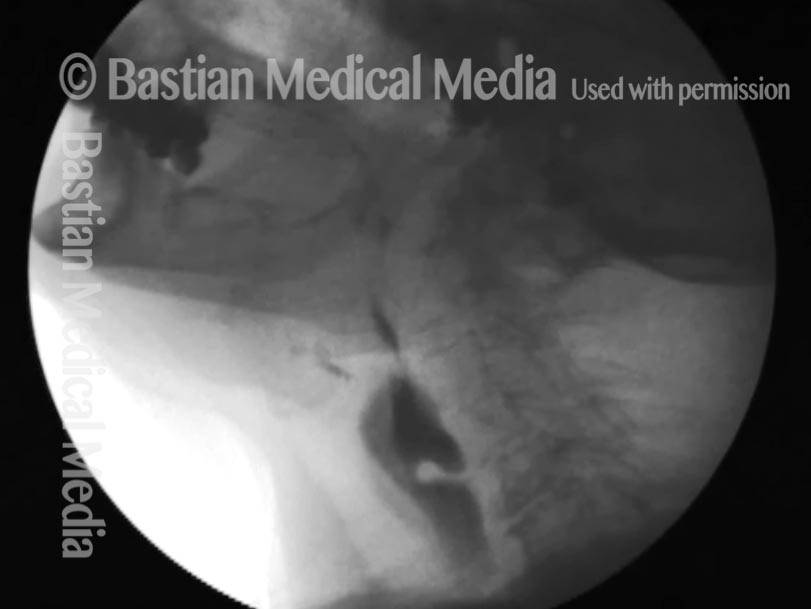

Cricopharyngeal dysfunction: before myotomy (1 of 2)

Cricopharyngeal dysfunction: before myotomy (1 of 2)

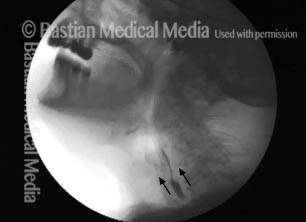

Cricopharyngeal dysfunction: after myotomy, resolved (2 of 2)

Cricopharyngeal dysfunction: after myotomy, resolved (2 of 2)

Example 2

Cricopharyngeal dysfunction: before myotomy (1 of 2)

Cricopharyngeal dysfunction: before myotomy (1 of 2)

Cricopharyngeal dysfunction: after myotomy, resolved (1 of 2)

Cricopharyngeal dysfunction: after myotomy, resolved (1 of 2)

Example 3

Cricopharyngeal dysfunction: before myotomy (1 of 2)

Cricopharyngeal dysfunction: before myotomy (1 of 2)

Cricopharyngeal dysfunction: after myotomy (2 of 2)

Cricopharyngeal dysfunction: after myotomy (2 of 2)

Cricopharyngeus Myotomy for Recreational Eating and Management of Saliva

Panormaic view, post CPM (1 of 4)

Panormaic view, post CPM (1 of 4)

Trumpet maneuver (2 of 4)

Trumpet maneuver (2 of 4)

Closer view (3 of 4)

Closer view (3 of 4)

Well-managed saliva (4 of 4)

Well-managed saliva (4 of 4)

98 year-old before and after Myotomy

Immediately after swallowing (1 of 10)

Immediately after swallowing (1 of 10)

Zenker’s (2 of 10)

Zenker’s (2 of 10)

Dysphagia (3 of 10)

Dysphagia (3 of 10)

Residue from Zenker’s (4 of 10)

Residue from Zenker’s (4 of 10)

X-ray showing Zenker’s (5 of 10)

X-ray showing Zenker’s (5 of 10)

Moments later (6 of 10)

Moments later (6 of 10)

After myotomy (7 of 10)

After myotomy (7 of 10)

No residue (8 of 10)

No residue (8 of 10)

Zenker’s gone (9 of 10)

Zenker’s gone (9 of 10)

No barium in hypopharynx (10 of 10)

No barium in hypopharynx (10 of 10)

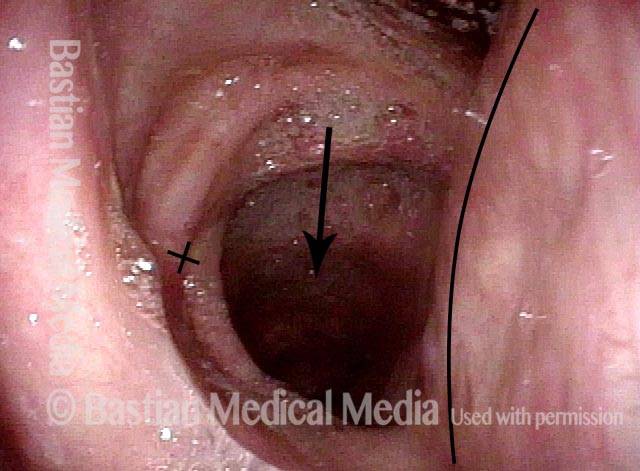

Great View of Fresh Cricopharyngeus Myotomy Surgical Wound

CPM dysfunction (1 of 4)

CPM dysfunction (1 of 4)

VFSS six years later (2 of 4)

VFSS six years later (2 of 4)

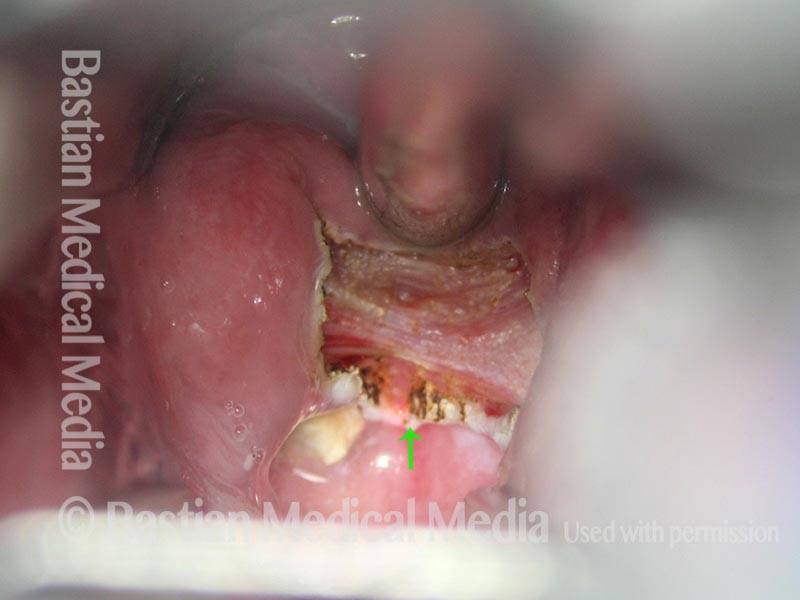

Five days post-op (3 of 4)

Five days post-op (3 of 4)

Cervical esopagus (4 of 4)

Cervical esopagus (4 of 4)

Bolus Stream before and after Cricopharyngeus Myotomy

Pre-myotomy (1 of 2)

Pre-myotomy (1 of 2)

Post-myotomy (2 of 2)

Post-myotomy (2 of 2)

VESS Findings after Radiotherapy

Narrowed pharyngeal wall (1 of 7)

Narrowed pharyngeal wall (1 of 7)

Swallowing applesauce (2 of 7)

Swallowing applesauce (2 of 7)

After sipping water (3 of 7)

After sipping water (3 of 7)

Gravity aiding in swallowing (4 of 7)

Gravity aiding in swallowing (4 of 7)

Lifting larynx (5 of 7)

Lifting larynx (5 of 7)

A closer look (6 of 7)

A closer look (6 of 7)

Gravity aiding again in swallowing (7 of 7)

Gravity aiding again in swallowing (7 of 7)

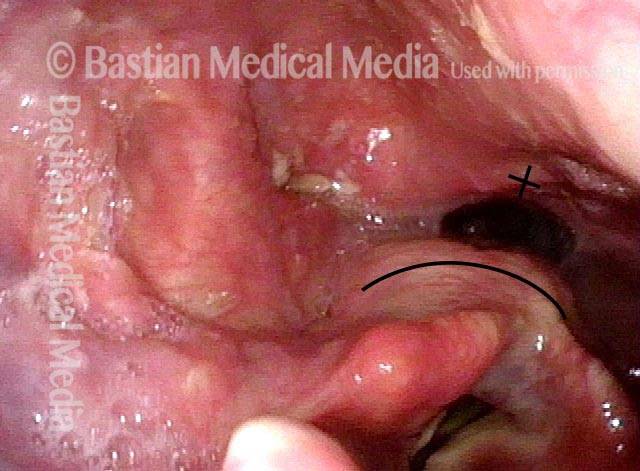

The Evolution of a Cricopharyngeus Myotomy Wound

Difficulty swallowing solid foods (1 of 8)

Difficulty swallowing solid foods (1 of 8)

Pooled saliva (2 of 8)

Pooled saliva (2 of 8)

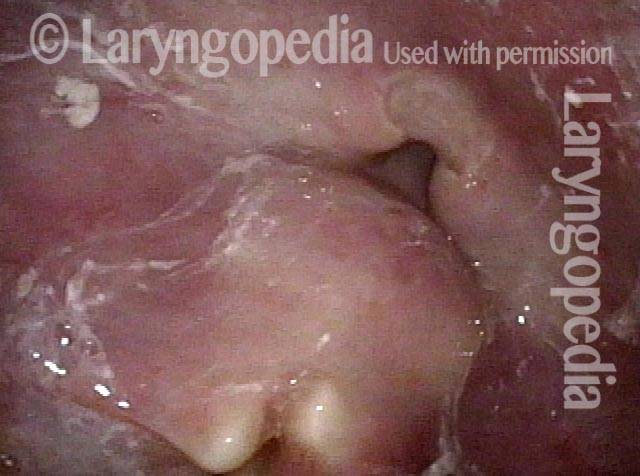

Muscle bulge (3 of 8)

Muscle bulge (3 of 8)

Residue in swallow crescent (4 of 8)

Residue in swallow crescent (4 of 8)

Three weeks later (5 of 8)

Three weeks later (5 of 8)

Residual “wound” (6 of 8)

Residual “wound” (6 of 8)

Three months post-op (7 of 8)

Three months post-op (7 of 8)

At close range (8 of 8)

At close range (8 of 8)

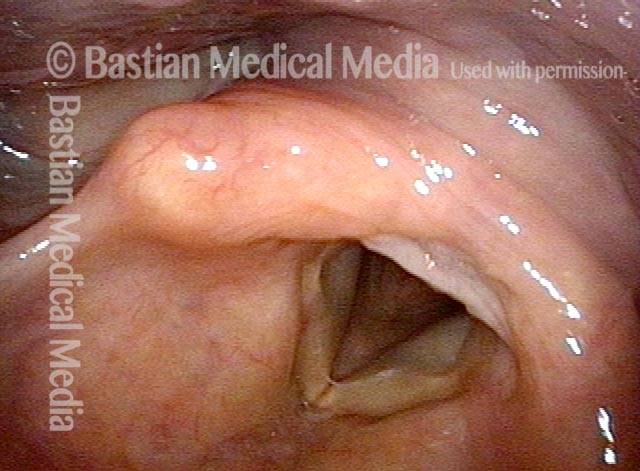

Zenker’s Diverticulum a Week after Cricopharyngeus Myotomy

Zenker’s Sac (1 of 3)

Zenker’s Sac (1 of 3)

Zenker’s Sac (2 of 3)

Zenker’s Sac (2 of 3)

Zenker’s Sac (3 of 3)

Zenker’s Sac (3 of 3)

Share this article

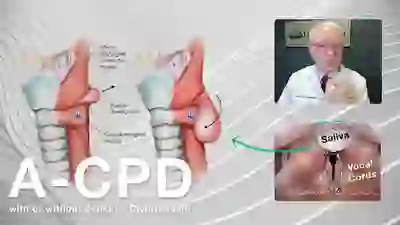

A-CPD Can Be Treated with Cricopharyngeal Myotomy

A small percentage of (mostly) older people develop a progressive but treatable swallowing disorder called antegrade cricopharyngeal dysfunction (A-CPD). They have difficulty initially with solid foods and pills.

As the months and years pass, the tendency for food to lodge in the throat gradually increases. Eventually, they must limit their diets to softer and “easier” things more and more like “baby food.” Special focus is placed on an effective endoscopic (through the mouth) laser procedure: cricopharyngeal myotomy.

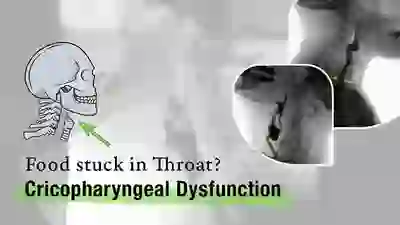

Cricopharyngeal Dysfunction: Before and After CPM

This video shows x-rays of barium passing through the throat, first with a narrowed area caused by a non-relaxing upper esophageal sphincter (cricopharyngeus muscle), and then after laser division (myotomy) of this muscle.

Preoperatively, food and pills were getting stuck at the level of the mid-neck, and the person was eating mostly soft foods. After the myotomy, the patient could again swallow meat, pizza, pills, etc. without difficulty.

Swallowing Trouble 101

This video gives an overview of how swallowing works, how it can sometimes go wrong (presbyphagia or A-CPD), and possible ways to treat those problems (swallowing therapy or cricopharyngeal myotomy).

What if my teeth feel loose after CPM?

Refrain from wiggling them, or from biting into tough foods until they tighten back up on their own. Most often this takes a week or so.

When should I see my doctor after the procedure?

About six weeks after surgery a video-fluoroscopic swallowing study (VFSS) is scheduled to compare with the one you had before surgery.

You bring a videotape copy of that study with you to a postoperative visit with your surgeon later the same day the VFSS was done.

What post-op symptoms would require immediate attention?

All of the following are very unlikely, but they are:

- Inability to swallow liquids.

- Chest or back pain increasing in severity from the time of surgery.

- Fever or chills.

- Anything else at all that causes you concern!

How will I know in advance which way the surgery will be done?

Candidates for CPM should agree to both methods. That way, the surgeon can attempt his or her preferred method from within the esophagus. If that method is not possible, they will switch to CPM through a neck incision.

Most people want to know when they leave the operating room if the problem will have been addressed, “one way or the other.”

If dysphagia occurs years after surgery, can CPM be performed again?

The 2 primary explanations I have encountered in a large series:

- The prior surgeon did not perform a complete myotomy, and/or;

- It is now many years later, the individual is truly elderly, and having trouble not with the sphincter but with the vigor of the propulsive side of swallowing.