Sensory Neuropathic Cough (SNC)

When coughing doesn’t stop.

Sensory Neuropathic Cough (SNC) is a chronic cough disorder that is thought to have a neurogenic cause.

SNC1 is also sometimes referred to as a cough caused by “laryngeal sensory neuropathy,” or is sometimes grouped within the more general category of “refractory chronic cough.”

Symptoms of Sensory Neuropathic Cough

A person with SNC may cough dozens to hundreds of times per day, often also waking up at night to cough. A few of these daily coughing attacks may become violent and last 30 seconds to several minutes. The person’s eyes may tear up and the nose may run; the person may gag or throw up; the person may leak urine, or worse; a few of our patients have even broken one or more ribs during a violent coughing attack.

A key characteristic of SNC is that a coughing attack is typically, though not always, preceded by an abrupt sensation in the throat; this sensation may be described as a “tickle,” a “sudden dry patch,” “like inhaling a powdered doughnut,” “dripping mucus,” or something else.

Possible Explanation for SNC

SNC is thought to be a relative to neuralgia, like post-herpetic neuralgia (persistent pain long after an outbreak of shingles has resolved), or even diabetic neuropathy (“I feel bees stinging my feet”), except that the sensations felt by SNC patients are not painful. With SNC, it may be that the nerve endings in a person’s throat have become damaged, so that they “misfire” and cause this cough-provoking tickling or similar sensations.

Treatment for SNC

Many individuals with SNC have found relief through use of a neuralgia medication, such as amitriptyline 2, desipramine 3, gabapentin 4, pregabalin, oxcarbazepine, and others. These kinds of medications may help to reduce or abolish a person’s coughing by diminishing the nerve-ending “misfires” caused by SNC.

In our experience, patients sometimes need to work through more than one of these neuralgia medication options, at varying dosage levels, before they arrive at a satisfactory degree of relief. Another treatment option that can be tried is capsaicin5. For more about treatment, see our second video (SNC: Medications) below.

What causes SNC?

Nobody knows for certain what causes SNC. We have a number of patients whose SNC began soon after a shingles outbreak in the throat. Others began to cough not long after thyroidectomy or other neck surgery. A very large number describe the beginning soon after an upper respiratory infection–usually a memorable one.

Suppose we could prove that SNC/ laryngospasm was caused by a viral injury. In that case, it would not be seen as a continuing infection, but instead as a chronic neural injury. Think, for example, of the post-herpetic neuralgia that can be permanent after a shingles (herpes zoster) outbreak. Treating with antivirals, say a few months after the infection and after the neural injury had occurred would not be expected to heal the damaged nerve endings. Or an extreme example just to send the point home: If a person lost an arm due to the “flesh-eating” streptococcus, treating for streptococcus a month after the loss of the arm (and resolution of the infection) would not restore the arm.

Viruses often seem to have a kind of “tropism.” Ever notice how some upper respiratory infections spread through a family, and seem to have highly similar effects? Everyone starts with scratchy throat, then the nose runs, then the cough starts. Etc. One solution could be a “virus” shared by three family members that had similar effects on all of them. If sensory neuropathic cough were in fact a virus-induced neural injury, then it would be possible that more than one member of a family could develop SNC. It is interesting that I have many patients whose mother, or sister, etc. also have SNC. Did they share a virus? Or is it a genetic “susceptibility” in families?

How do I find a doctor for SNC?

Call the otolaryngology (ENT) department of a nearby university or other large medical center. Ask to speak to the triage nurse. Ask that nurse if there are one or more doctors there who have a special interest in neurological coughing. You may need to make a few different phone calls to find a doctor in your area known to have this particular interest.

If you can’t find any such doctors, you might also try calling the pulmonary departments of nearby universities or large medical centers. Or, alternatively, you might simply share the information you found about sensory neuropathic cough with your primary care physician and ask, “Could I please try low-dose amitriptyline?”

As a last resort, you would of course also be welcome to come to our office in the Chicago area. After that first visit, Dr. Bastian would (if your diagnosis is indeed sensory neuropathic cough) be able to manage your treatment from a distance. But of course, for most people it’s not possible to travel so far.

Table of Contents

Tags

Audio · Chronic cough · Cough · Coughing disorders · Disorders · Photos · Sensory Neuropathic Cough (SNC) · Videos

Audio Examples of SNC

Photos of SNC

A collection of photo essays demonstrating SNC in various patients.Bruising from Sensory Neuropathic Cough

Closer view of bruise (2 of 2)

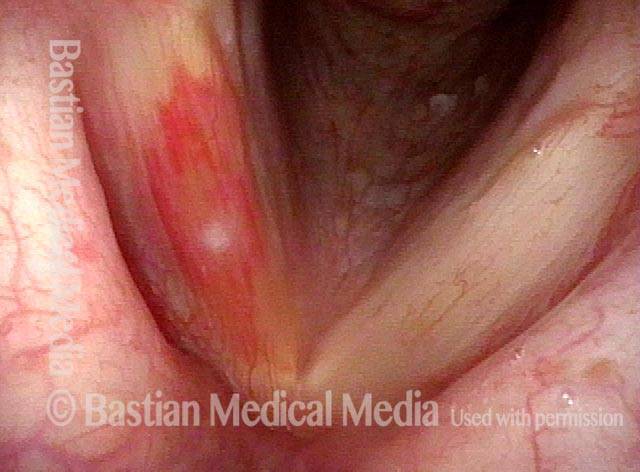

Bruise caused by violent coughing (1 of 2)

Bruise caused by violent coughing (1 of 2)

Closer view of bruise (2 of 2)

Example 2

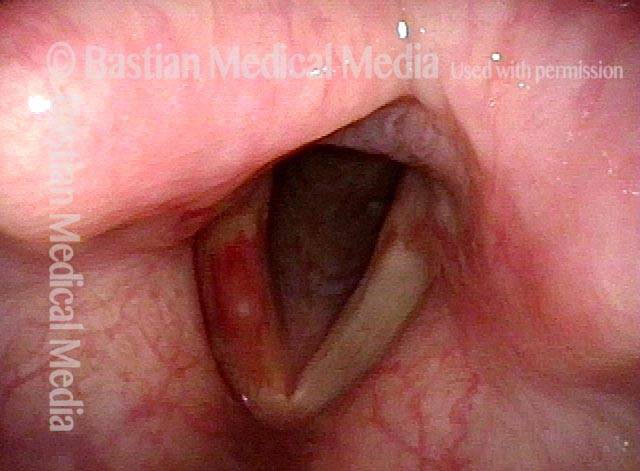

Bruise from coughing (1 of 3)

Bruise from coughing (1 of 3)

Pre-phonatory instant (2 of 3)

Pre-phonatory instant (2 of 3)

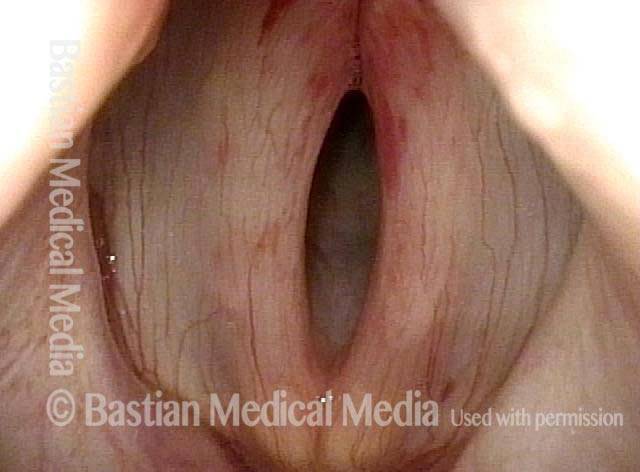

Phonation (3 of 3)

Phonation (3 of 3)

Example 3

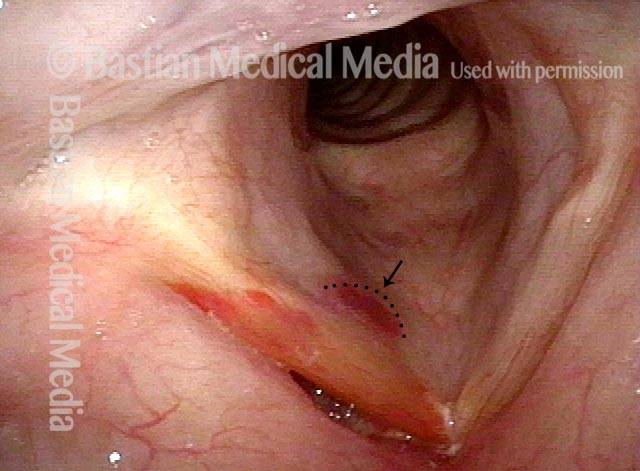

Bruising from SNC (1 of 1)

Bruising from SNC (1 of 1)

Hemoptysis

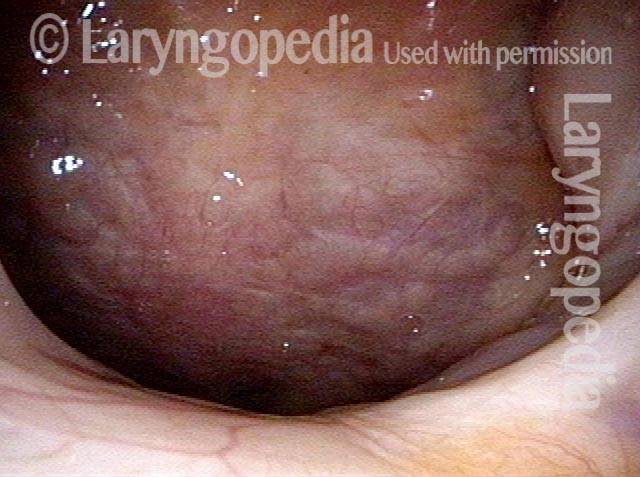

SNC patient (1 of 6)

SNC patient (1 of 6)

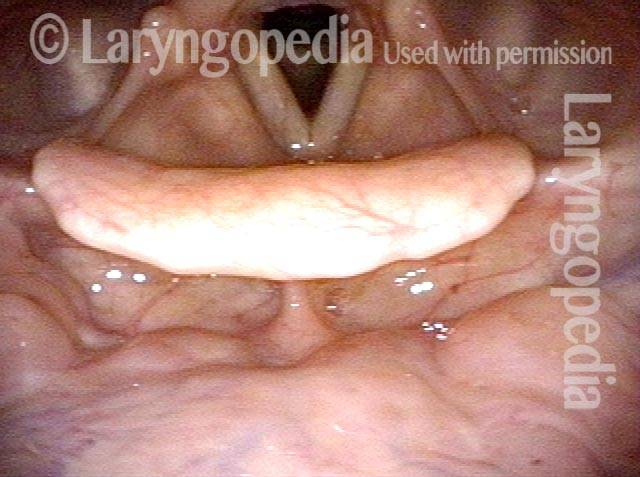

Panoramic view (2 of 6)

Panoramic view (2 of 6)

Lidocaine (3 of 6)

Lidocaine (3 of 6)

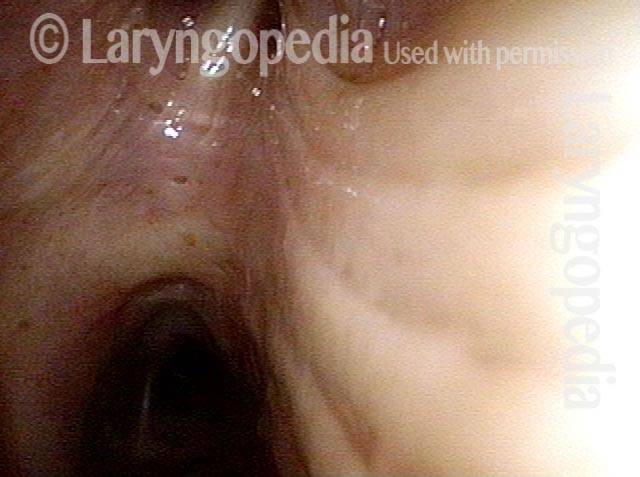

Carina (4 of 6)

Carina (4 of 6)

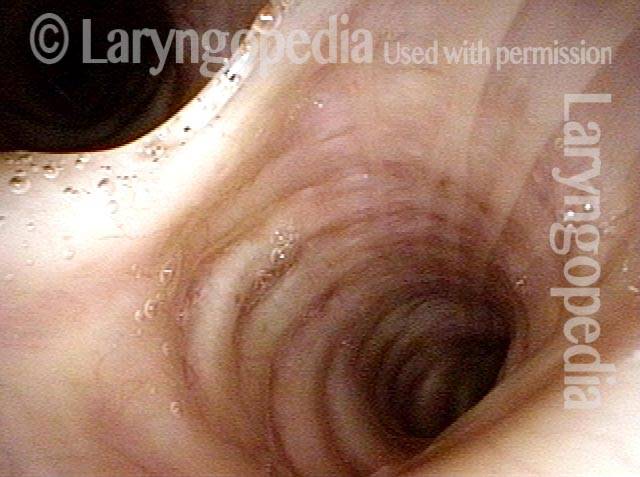

Right mainstem bronchus (5 of 6)

Right mainstem bronchus (5 of 6)

Left mainstem bronchus (6 of 6)

Left mainstem bronchus (6 of 6)

Videos about SNC

SNC, Part I: Coughing That Won’t Go Away

Sensory neuropathic cough is a chronic cough condition that does not respond to the usual treatments. Many individuals who have been coughing for years find relief from treatment with “neuralgia” medications.

SNC Part II: Medications

Dr. Bastian continues from SNC, Part I and introduces potential medications to treat sensory neuropathic cough.

Still Coughing After COVID?

In this video, Dr. Robert W. Bastian explains three explanations for coughing in the context of Covid-19 infection, with emphasis on the potential for sensory neuropathic cough (Phase 3).

Phantom Phlegm!!

Patients with Sensory Neuropathic Cough (SNC) comment on feeling mucus drip down their throats, but often…it isn’t there!Share this entry

Additional Resources

View additional information about SNC on our website:

Journal Entries

Sensory Neuropathic Cough Need Not Be a Diagnosis of Exclusion

Treatment for Sensory Neuropathic Cough

Medical Jadedness and Treatment of Sensory Neuropathic Cough

A Trail to Sensory Neuropathic Cough

The Use of Capsaicin for Sensory Neuropathic Cough

Still Coughing After COVID-19?

When Mucus Seems to Be Causing Your Cough or Throat Clearing – But Isn’t

SNC Publications

Hoesli RC, Wingo ML, Wajsberg B, Bastian RW. Topical capsaicin for the treatment of sensory neuropathic cough. OTO Open 2021; 5: 2473974X211065668.