Zenker’s Diverticulum

Zenker’s Diverticulum (ZD) is an outpouching or, in effect, a hernia of the swallowing passage just above a non-relaxing cricopharyngeus muscle.

In essence, the forces of swallowing are delivered against a somewhat unyielding muscle, and this causes the wall of the swallowing passage just above the cricopharyngeus muscle (i.e., the upper esophageal sphincter) to balloon outward. Hence, unknown to many, the Zenker’s diverticulum is only the reflection of the main problem, which is cricopharyngeal dysfunction.

Treatment for ZD

Myotomy of the cricopharyngeus muscle tends to resolve symptoms, even though the Zenker’s diverticulum is left in place and not removed.

Photo Essays of Zenkers Diverticulum

Zenker’s diverticulum (1 of 4)

Zenker’s diverticulum (1 of 4)

Saliva from Zenker’s sac (2 of 4)

Saliva from Zenker’s sac (2 of 4)

More saliva (3 of 4)

More saliva (3 of 4)

Forced to re-swallow (4 of 4)

Forced to re-swallow (4 of 4)

Example 2

Zenker’s diverticulum (1 of 3)

Zenker’s diverticulum (1 of 3)

Postcricoid area (2 of 3)

Postcricoid area (2 of 3)

Hypopharynx (3 of 3)

Hypopharynx (3 of 3)

Post-swallow Return of Saliva into the Hypopharynx

This man began to experience solid food lodgment a few years earlier, along with gurgling noises every time he swallows. Even on an initial examination, Zenker’s diverticulum can be strongly suspected based on the findings of the videoendoscopic swallow study (VESS). Upon review of a videofluoroscopic swallow study (VFSS), a Zenker’s diverticulum is indeed the explanation for the findings below, which went away completely (return of saliva, gurgling noises, and food lodgment) after myotomy.

Pooling of saliva (1 of 4)

Pooling of saliva (1 of 4)

Saliva disappears after swallow (2 of 2)

Saliva disappears after swallow (2 of 2)

Saliva begins to return (3 of 3)

Saliva begins to return (3 of 3)

Saliva is ejected upwards from Zenker’s sac (4 of 4)

Saliva is ejected upwards from Zenker’s sac (4 of 4)

Reflux Into Hypopharynx, Characteristic of Cricopharyngeal Dysfunction

Reflux into hypopharynx (1 of 3)

Reflux into hypopharynx (1 of 3)

Water flows into the swallowing crescent (2 of 3)

Water flows into the swallowing crescent (2 of 3)

Larynx opens up (3 of 3)

Larynx opens up (3 of 3)

Videoendoscopic View of Zenker’s Sac Opening and Cricopharyngeus Bar

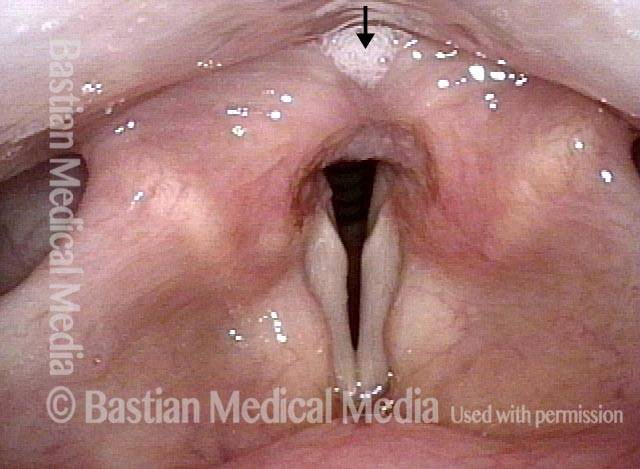

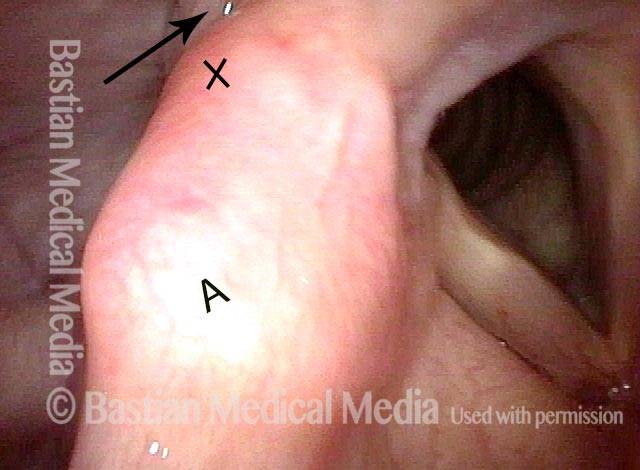

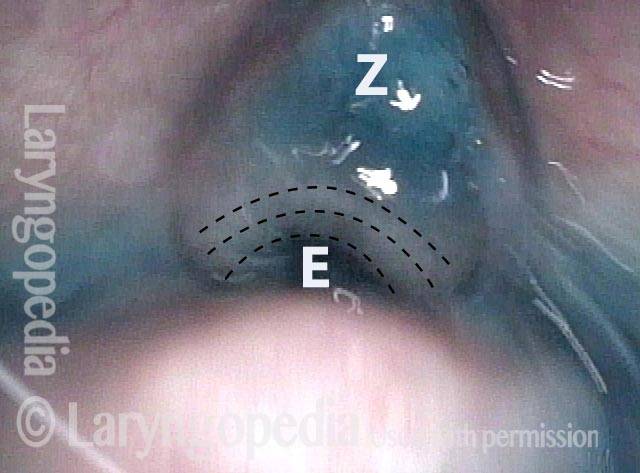

Orientation (1 of 4)

Orientation (1 of 4)

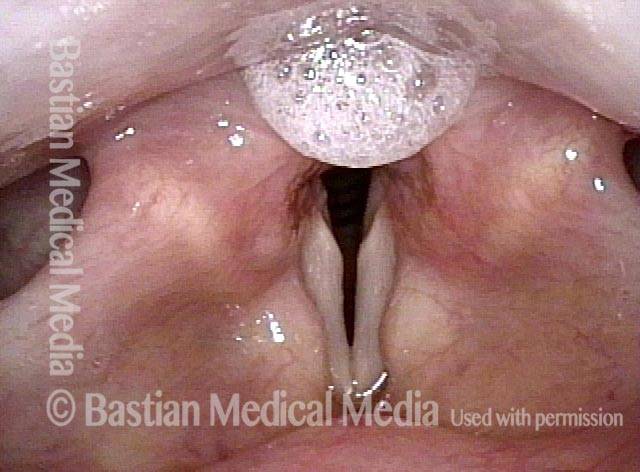

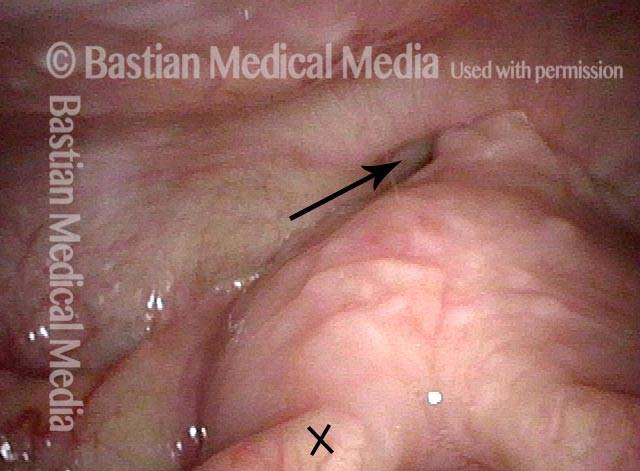

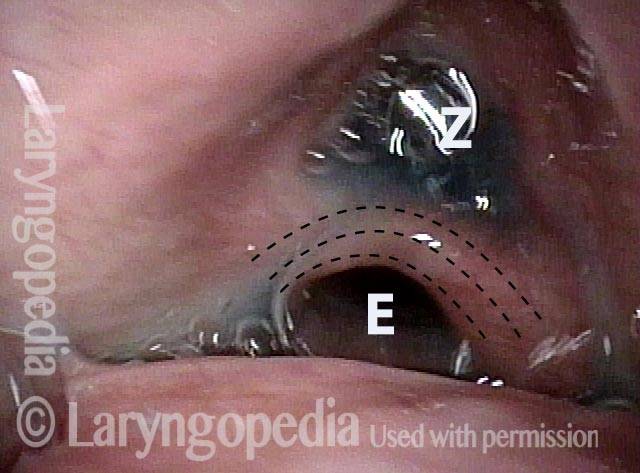

View into post-arytenoid and post-cricoid area (2 of 4)

View into post-arytenoid and post-cricoid area (2 of 4)

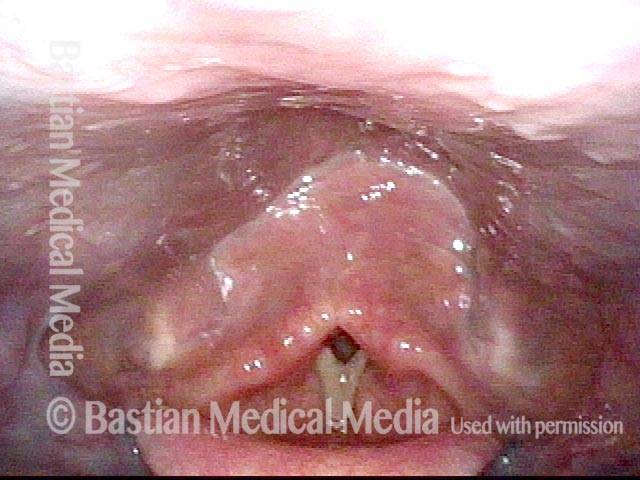

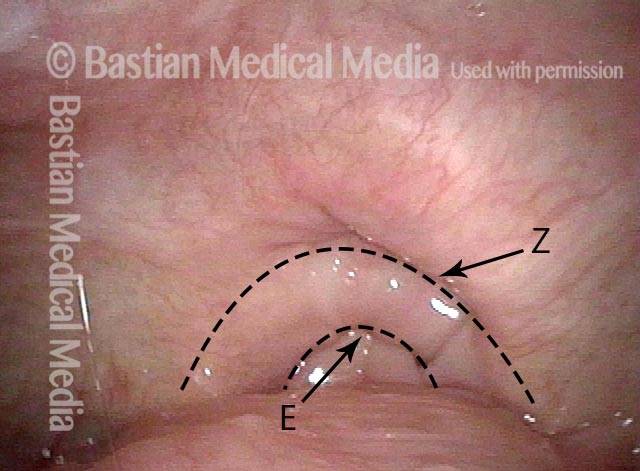

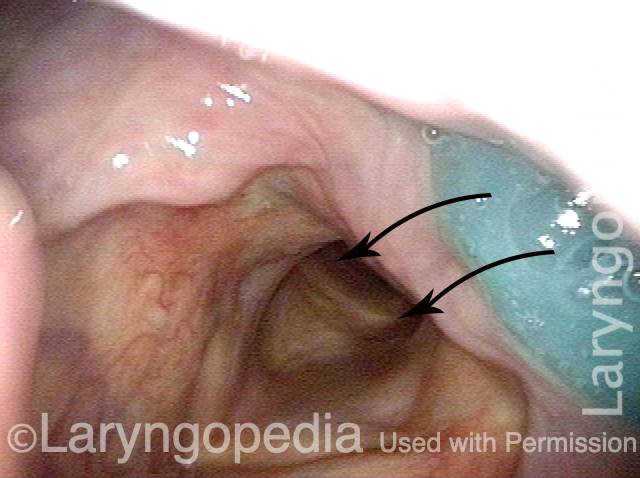

Esophageal and Zenker sac openings (3 of 4)

Esophageal and Zenker sac openings (3 of 4)

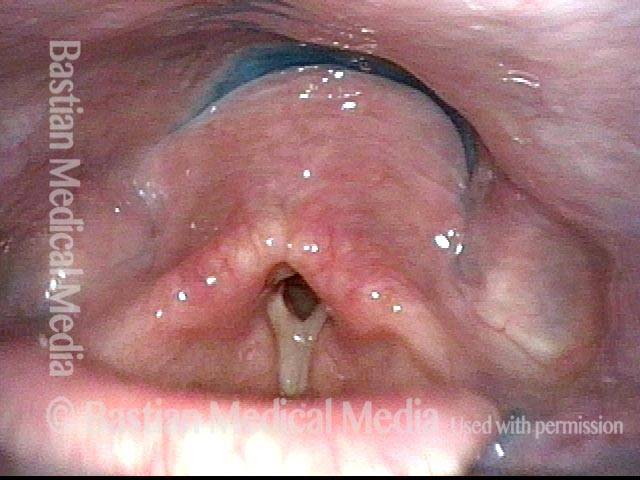

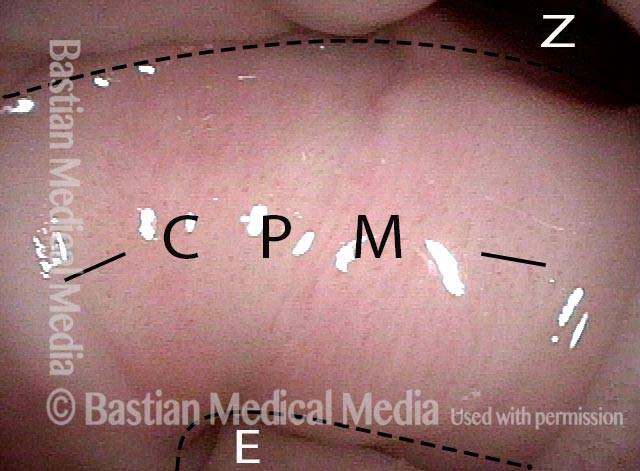

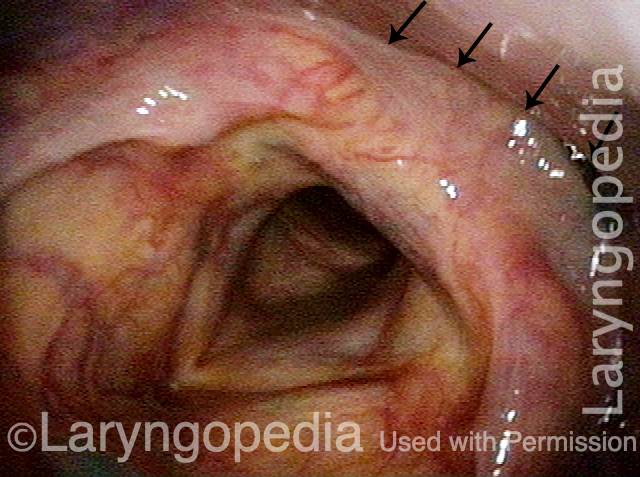

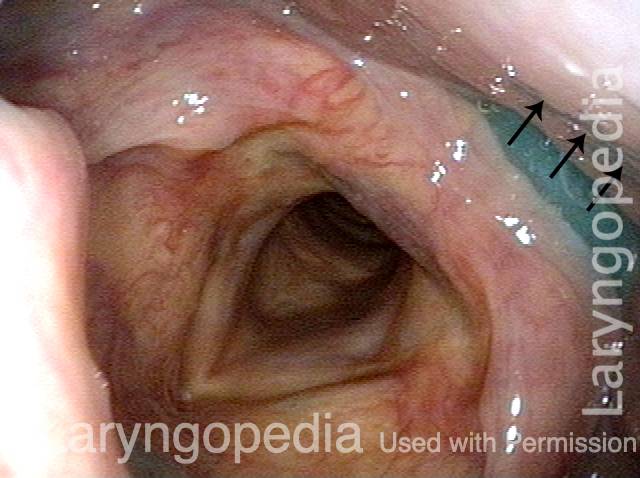

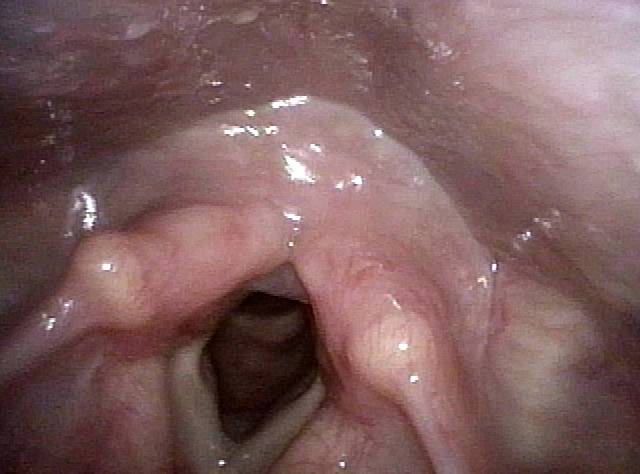

Cricopharyngeus muscle bar (4 of 4)

Cricopharyngeus muscle bar (4 of 4)

Cricopharyngeus Non-Relaxation and Zenker’s Sac Seen During VESS

Immediately after swallow (1 of 4)

Immediately after swallow (1 of 4)

One second later (2 of 4

One second later (2 of 4

Un-relaxed cricopharyngeus muscle (3 of 4)

Un-relaxed cricopharyngeus muscle (3 of 4)

More water (4 of 4)

More water (4 of 4)

Zenker’s Diverticulum Returns Its Contents Upwards to the Throat After Each Swallow

VESS (1 of 3)

VESS (1 of 3)

Swallowing Crescent (2 of 3)

Swallowing Crescent (2 of 3)

Applesauce spills into airway (3 of 3)

Applesauce spills into airway (3 of 3)

Post-swallow Hypopharyngeal Reflux (Zenker’s Diverticulum): VESS vs. VFSS

VESS (1 of 7)

VESS (1 of 7)

Reflux (2 of 7)

Reflux (2 of 7)

Post-swallow (3 of 7)

Post-swallow (3 of 7)

Reflux of cracker (4 of 7)

Reflux of cracker (4 of 7)

VFSS (5 of 7)

VFSS (5 of 7)

X-Ray (6 of 7)

X-Ray (6 of 7)

Continued reflux (7 of 7)

Continued reflux (7 of 7)

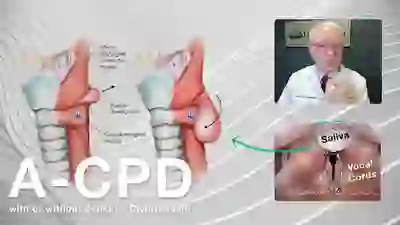

A-CPD with or without Zenker’s Diverticulum

A small percentage of (mostly) older people develop a progressive but treatable swallowing disorder called antegrade cricopharyngeal dysfunction (A-CPD). They have difficulty initially with solid foods and pills.

As the months and years pass, the tendency for food to lodge in the throat gradually increases. Eventually, they must limit their diets to softer and “easier” things more and more like “baby food.” Special focus is placed on an effective endoscopic (through the mouth) laser procedure: cricopharyngeal myotomy.