Amyloidosis is a disorder caused by deposition of immunoglobulin-like proteinaceous material into one or more organs of the body. This disease process can be described as either primary or secondary.

Secondary Amyloidosis

In secondary amyloidosis, abnormal B cells (part of the white blood cell family) overproduce these proteins, which are then deposited throughout the body: in heart muscle, tongue, gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, etc. An example of a disease causing secondary amyloidosis is multiple myeloma, a blood disease.

Primary Amyloidosis

An example of primary amyloidosis is when the deposits are found only in a single organ or location. This seems to be the case when amyloidosis affects the larynx.

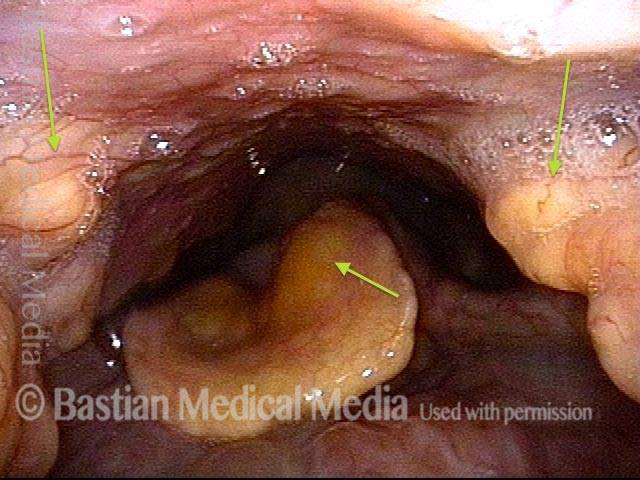

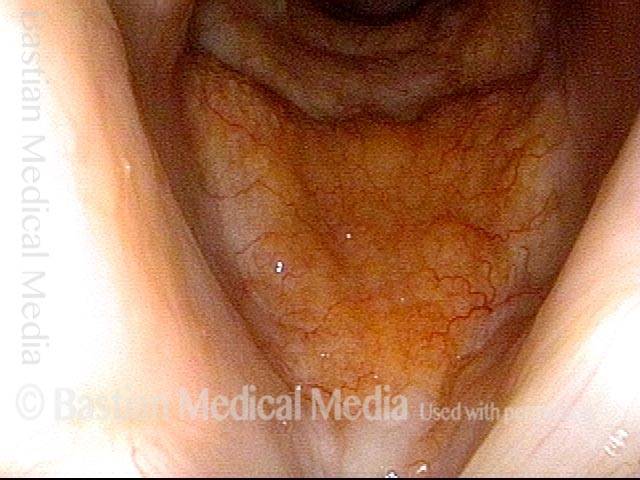

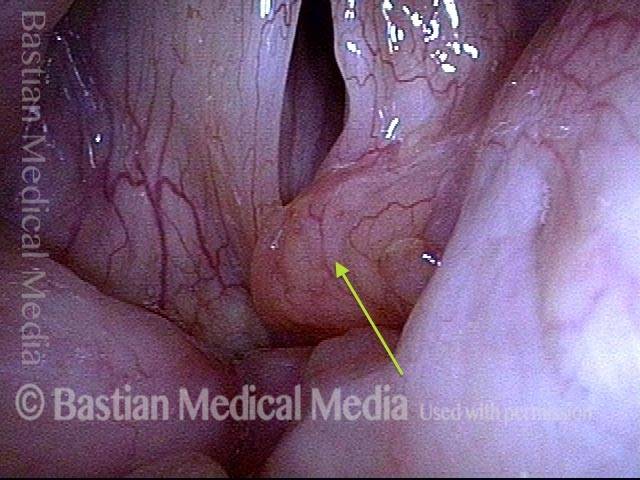

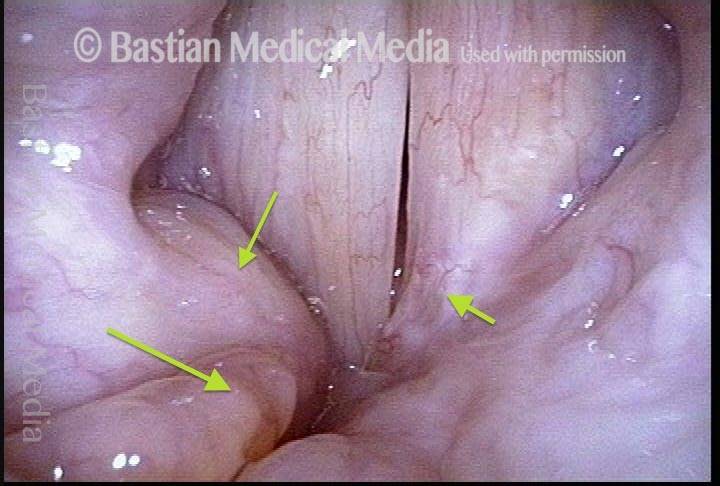

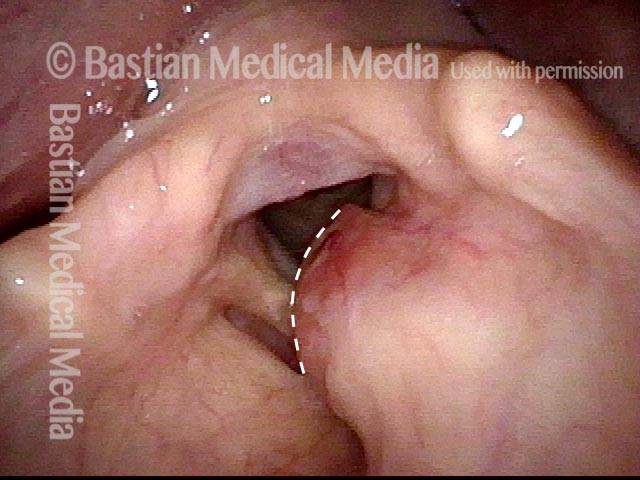

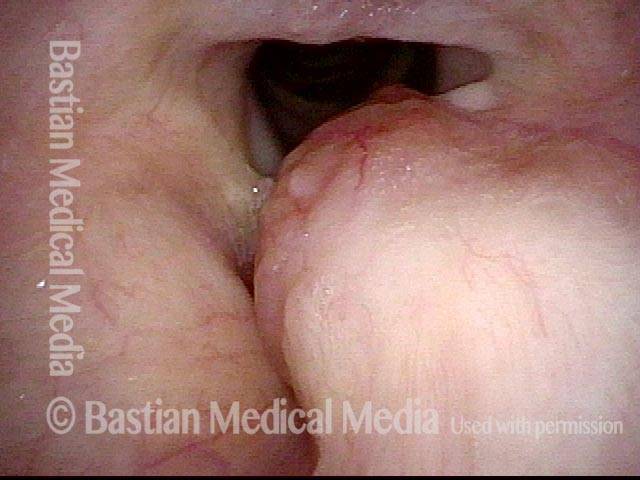

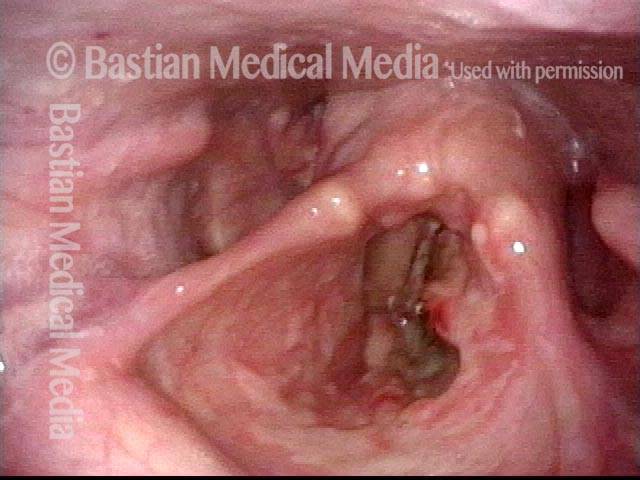

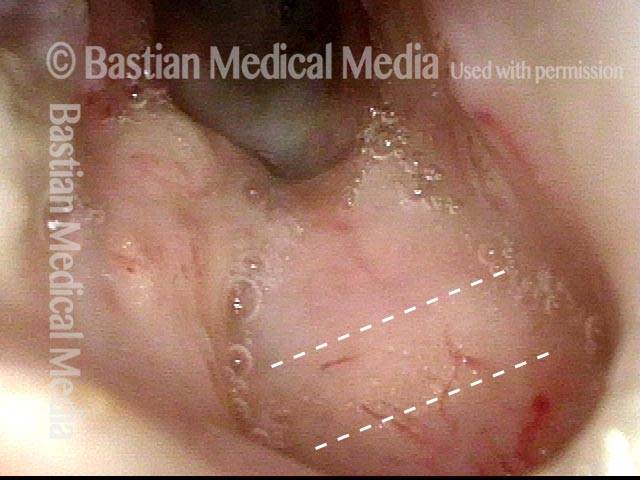

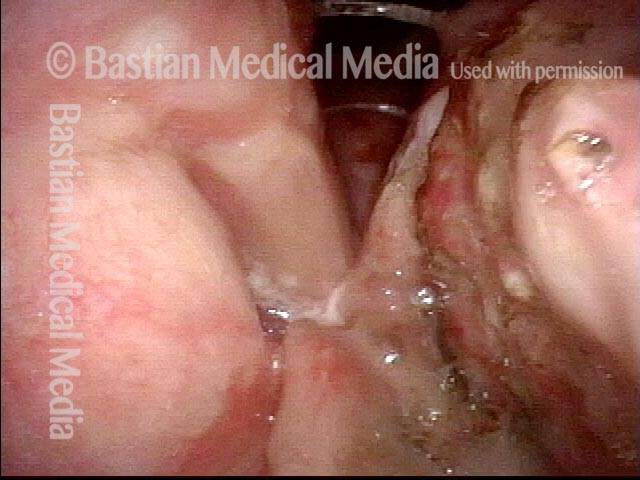

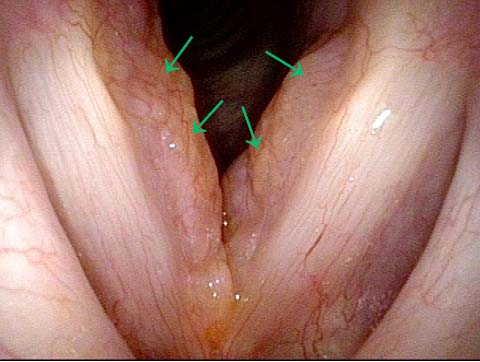

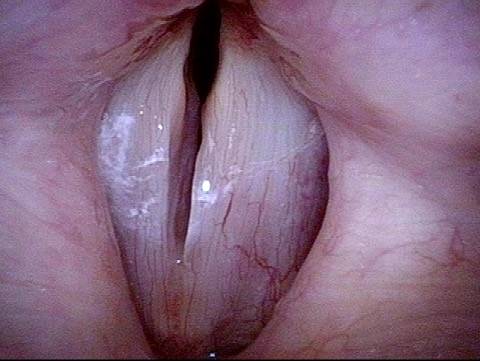

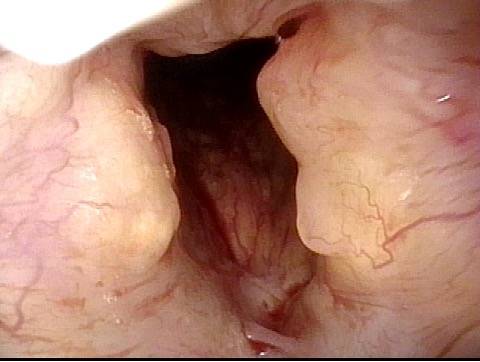

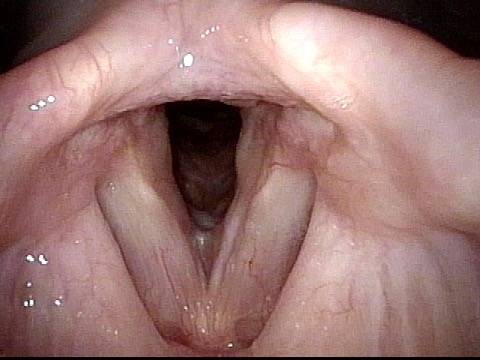

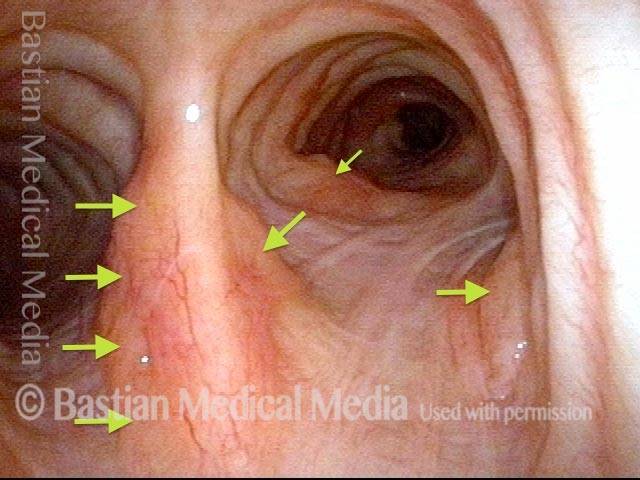

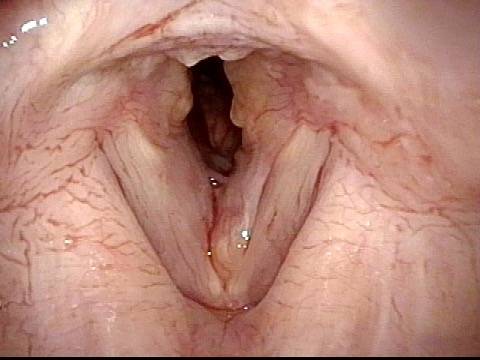

Amyloidosis in the Larynx

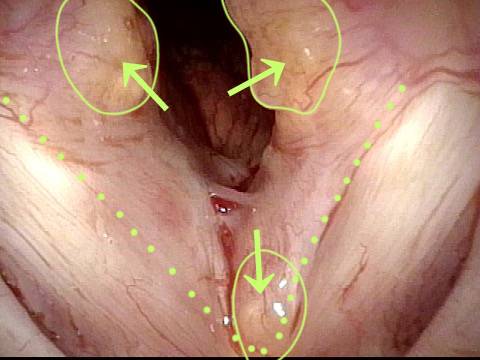

In laryngeal amyloidosis, the deposits seem to be localized either just to the larynx, or to the larynx and pharynx. One sees what looks like yellowish candle wax within the tissues. The amyloid deposits are quite firm, and when biopsied, there is little bleeding.

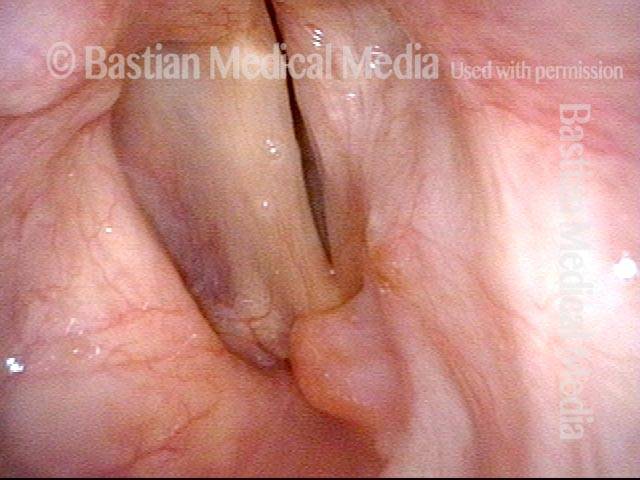

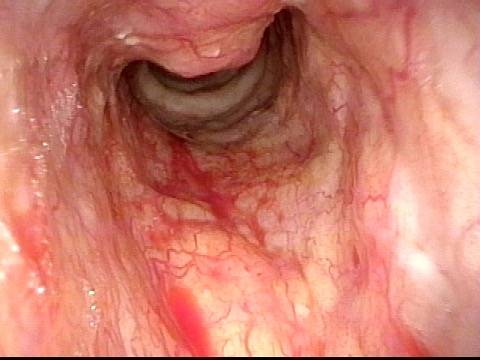

Treatment for Laryngeal Amyloidosis

Because of their infiltrative nature, amyloid deposits typically cannot all be dissected out of the larynx; instead, then, an operating physician will aim to debulk the deposits in areas where they impair breathing or the voice. That is, when deposits are widespread in the larynx, there does not seem to be any point in removing them except in locations where removal will improve function. Often, repeated procedures are required over many years’ time, though occasionally the condition seems to stop progressing.