Botox Placement for Treatment of Spasmodic Dysphonia in the “Fortress Larynx”

Introduction

Spasmodic dysphonia (SD) is what happens to the capabilities, limitations, and aberrations (vocal phenomenology) of the voice as the result of a rare neurological disorder called laryngeal dystonia. The prefix dys- essentially means “abnormal.” And so dystonia (abnormal tone in laryngeal muscles) causes dysphonia (abnormal sound of the voice).

Treatment for SD

While numerous treatments have been proposed and published for spasmodic dysphonia, a mainstay treatment continues to be injections of botulinum toxin into the tiny muscles of the larynx, between two and five times per year, with the commonest interval being every 4 months, or three times per year.

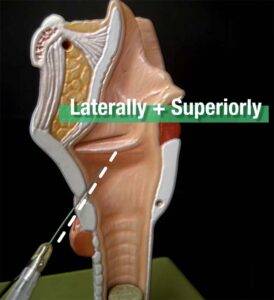

Botulinum toxin is most commonly delivered percutaneously under electromyographic guidance. The EMG needle is passed through the cricothyroid membrane (video example 🎥) and then angled laterally and superiorly to reach the vocal cord and the thyroarytenoid muscle that inhabits the cord.

When necessary, botulinum toxin can instead be delivered per-orally, using a video-endoscopic approach in the video endoscopy laboratory. Other “last resort” methods include injection through the thyroid cartilage; and rarely, using an oblique angulation from just above the margin of the thyroid cartilage in a downward direction.

Treatment in a Fortress Larynx

On occasion, none of these techniques for placement of the medication is possible. Consider the “perfect storm” circumstance of someone with more than one of the following:

- A powerful gag reflex who cannot tolerate the endoscopic method in an outpatient setting under topical anesthesia alone;

- Anatomical limitation like a fused cricothyroid space after prior trauma or surgery that prevents traditional cricothyroid membrane puncture and EMG guidance;

- The additional anatomical liability of unusually low larynx placement in the neck, such that the cricothyroid space is at or below the sternal notch;

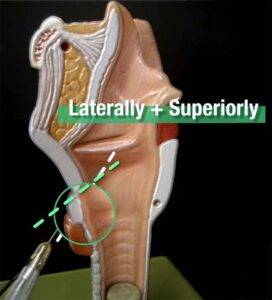

- An exceedingly narrow cricothyroid membrane with cricoid arch projecting much farther anteriorly than the inferior border of the thyroid cartilage, limiting ability to angle the EMG needle superiorly;

- Complete ossification of the thyroid cartilage making a (last-resort) injection through it and into the vocal cord muscle impossible.

To restate the difficulties caused by the above scenarios: the needle may not be angulated sufficiently superiorly to reach the thyroarytenoid muscle, even after creating a curve or bend in the needle.

If this individual also had major ossification of the thyroid cartilage, then injection via the trans-thyroid cartilage method becomes impossible. If such a person also has an unusually “tall” larynx, then reaching the vocal cord from the upper rim of the thyroid cartilage also becomes impossible.

In the author’s lifetime caseload of approximately 1500 patients, two male patients have fulfilled enough of these difficulties to make their injections unusually difficult for both the clinician and these patients because of repeated probing and searching with the needle in the face of anatomical impediments.

Furthermore, while “high quality” injections in the population as a whole should provide reasonably consistent and predictable results time after time, these two patients’results were quite variable due to the extreme difficulty targeting, and frequent “miss” of the muscles.

Description of a Solution to this Targeted Problem

In both cases, what initially seemed an extreme solution to the problem dramatically improved the ability to target laryngeal musculature. The patients were taken to the operating room in order to drill out large windows in the thyroid cartilage, purely to facilitate subsequent botulinum toxin injection. Under local infiltration anesthesia, a small incision was made in a skin crease, measuring 3 cm in length. The incision was carried through subcutaneous tissues to the level of the strap muscles. Strap muscles were dissected laterally to reveal the inferior third of each thyroid ala approaching the inferior border.

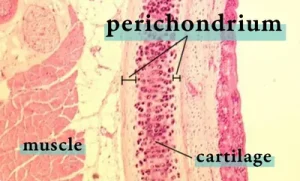

The external perichondrium was removed overlying a proposed cartilage window measuring approximately 8 x 16 mm. The reason for removal of external perichondrium was to reduce the likelihood of chondroneogenesis with sufficient calcification to again stop needle passage through the surgical window to the thyroarytenoid muscle.

The external perichondrium was removed overlying a proposed cartilage window measuring approximately 8 x 16 mm. The reason for removal of external perichondrium was to reduce the likelihood of chondroneogenesis with sufficient calcification to again stop needle passage through the surgical window to the thyroarytenoid muscle.

A 2 mm cutting bur was then used to drill away the thyroid cartilage completely overlying this large window. Inner perichondrium was carefully dissected from underlying thyroarytenoid muscle and also removed, again to avoid the problem of chondroneogenesis. The wound was then closed in layers and the patient discharged to home.

Conclusion

In the several years subsequent to this simple outpatient procedure, both patients have been injected at 4 month intervals, each time with far less discomfort and with far more consistent and beneficial results than was possible before the operative procedure.

It should be noted that in spite of the maneuvers described above to prevent chondroneogenesis, there is either dense scar or possibly some partial chondroneogenesis that creates a significant resistance to needle passage in one of the patients. It is not enough, however, to prevent successful injection.

Share this article

Table of Contents

Botox Injection Into the “Fortress Larynx” for SD

High quality Botox shots for spasmodic dysphonia (SD) can be defined as:

- Available on demand;

- Accomplished efficiently and with minimal discomfort;

- Providing consistent results.

Numbers 2 & 3 can be difficult to impossible when the patient has a “fortress larynx.“ In this video, we define this problem and a possible solution…