The term “long-haulers” has been used to refer to persons with lingering systemic symptoms after successful initial recovery from Covid-19. Symptoms such as coughing, fatigue, loss of taste and smell, brain fog, etc. occur weeks or months after first falling ill. Even some whose bout with Covid-19 seemed mild can experience this “long-haul” phenomenon. For more, here’s a link to a CDC publication describing this scenario before the words “long-haul” were attached to this syndrome.

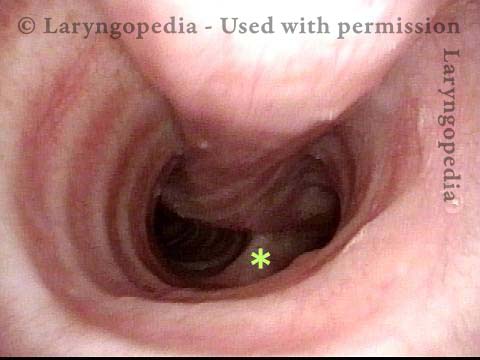

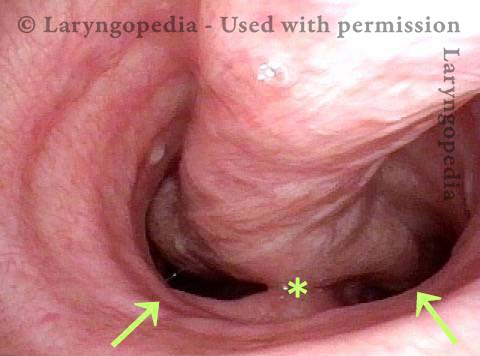

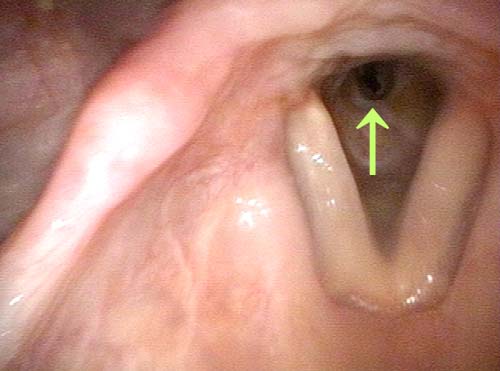

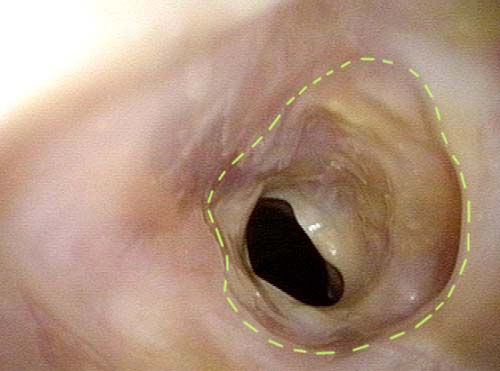

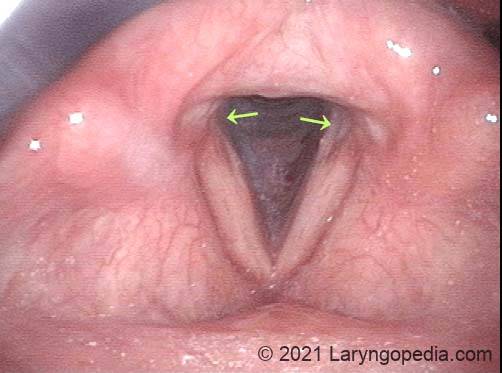

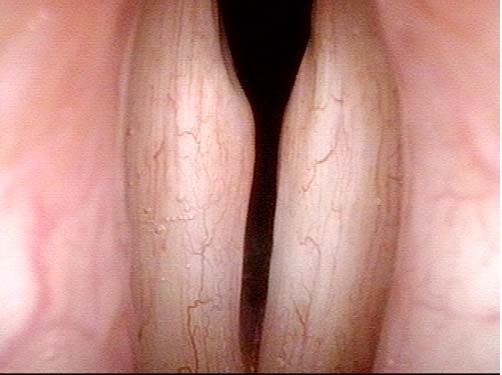

Laryngologists are now seeing patients weeks or months after their recovery from severe Covid-19 infection that required hospitalization and intubation/ventilation. These patients seem to be presenting primarily for chronic breathing and voice complaints. We are finding what could be called “long-haul” injuries from the breathing tube used while they were on ventilators. These injuries can be unavoidable when it is necessary to leave these breathing tubes in place for days to weeks due to grave illness. Such injuries in non-Covid patients are documented on Laryngopedia (see, for example: Intubation injury – Laryngopedia). Below are photos showing tracheal stenosis (narrowing), and post-intubation phonatory (voice) insufficiency, in “long-haul” breathing tube injury Covid-19 patients.