Vocal Polyps:

An Actress’ Polyp Before and Hours After Surgical Removal

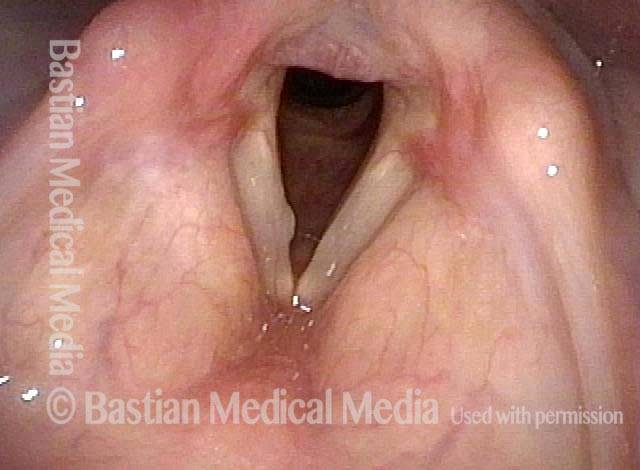

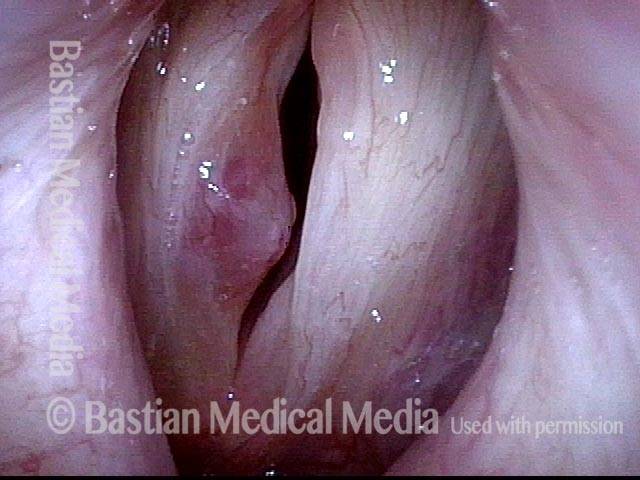

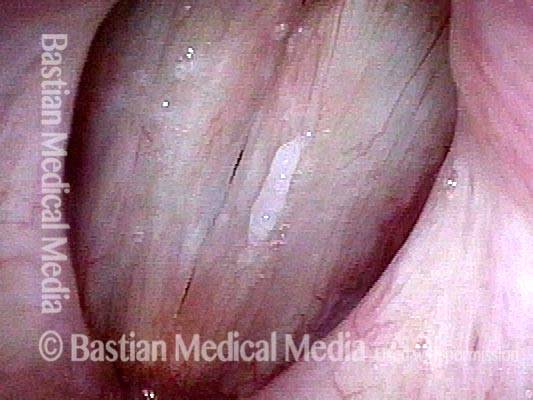

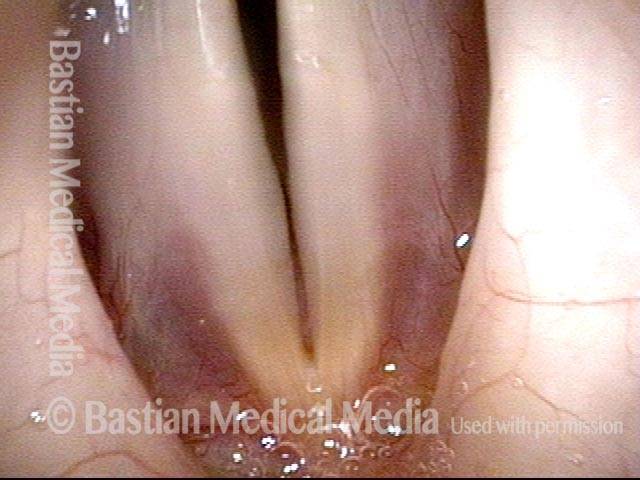

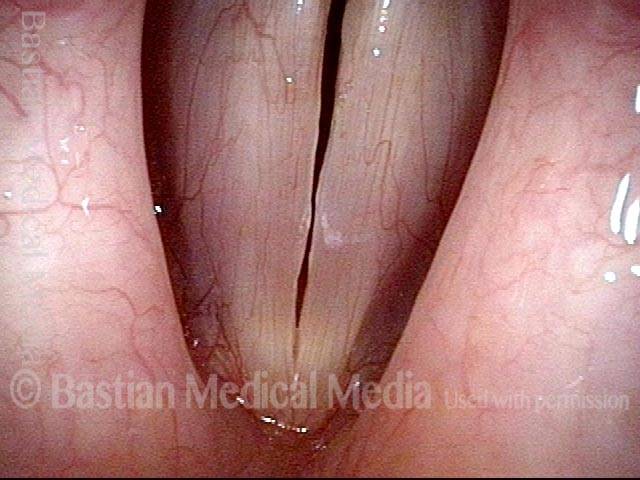

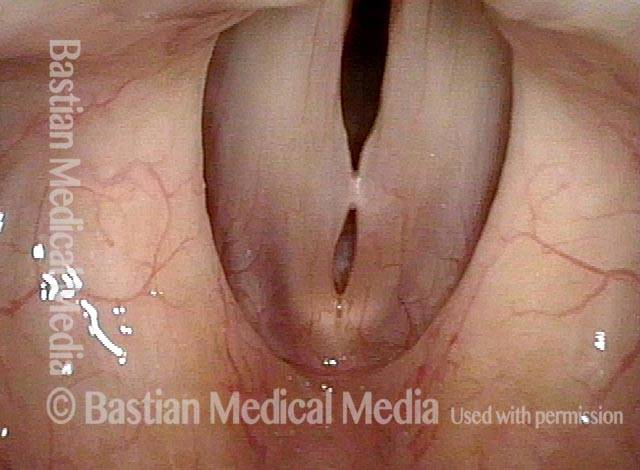

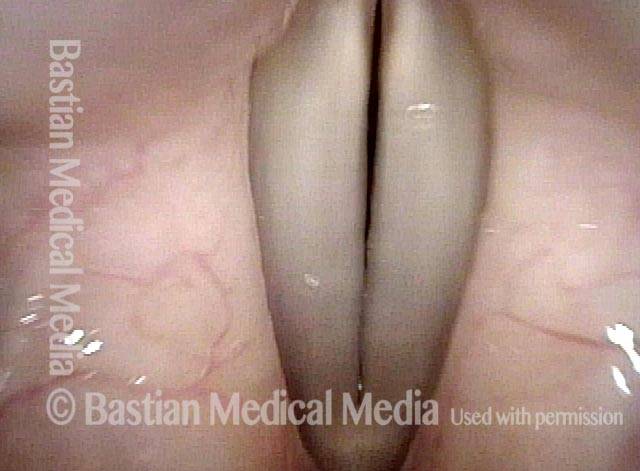

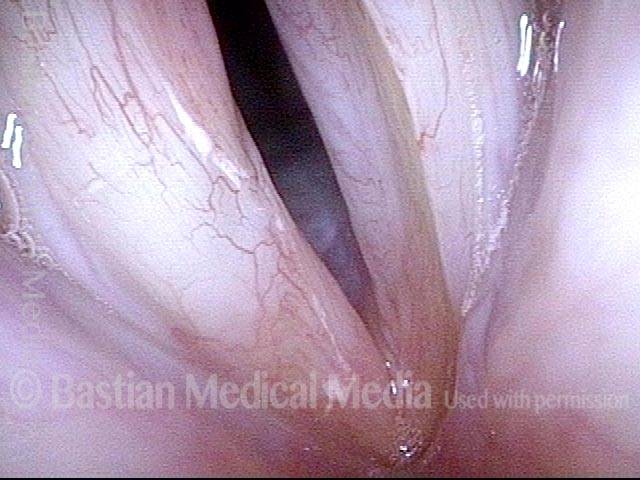

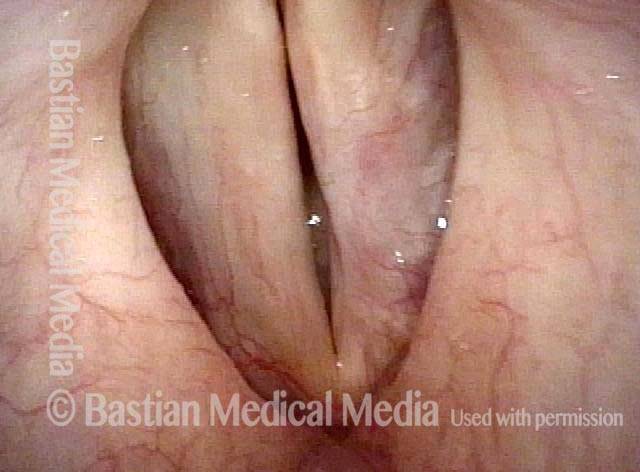

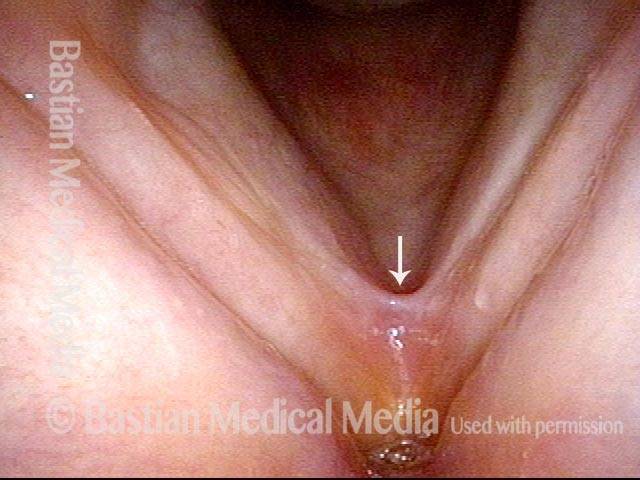

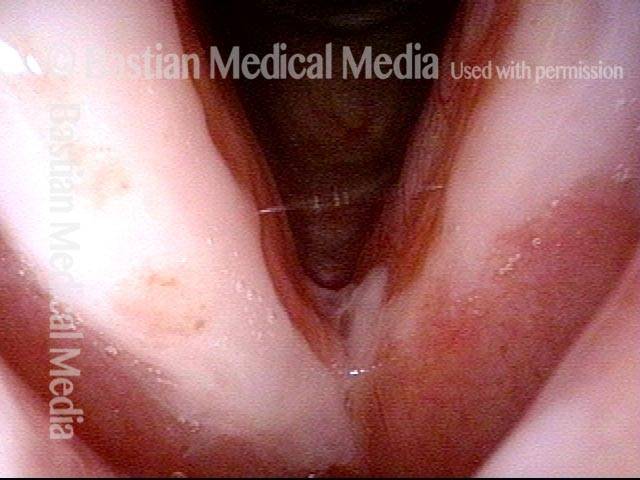

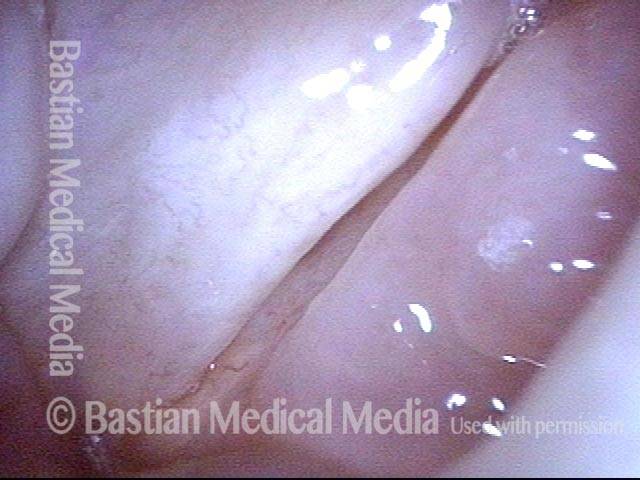

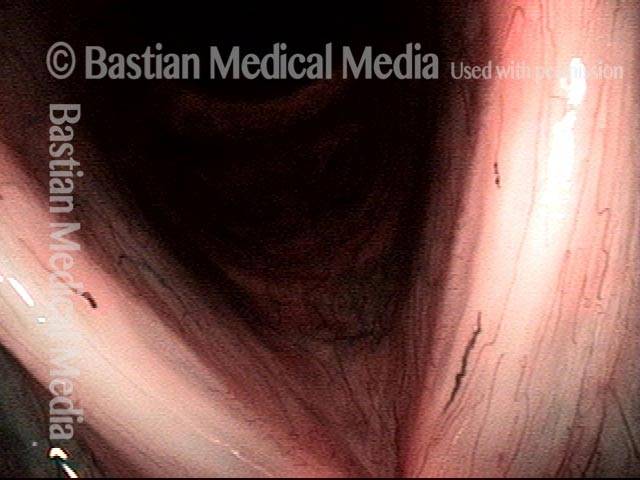

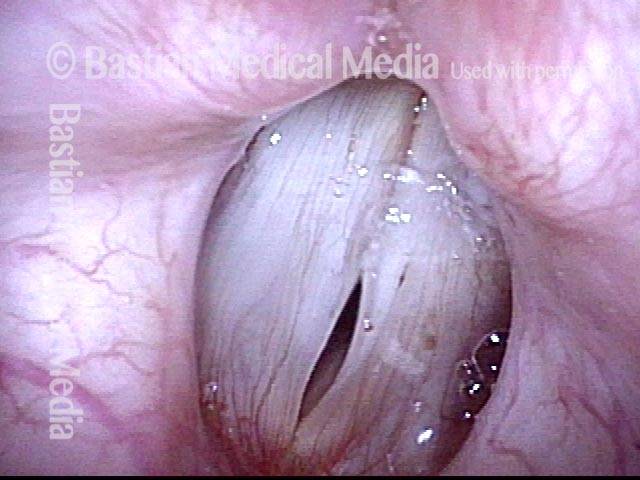

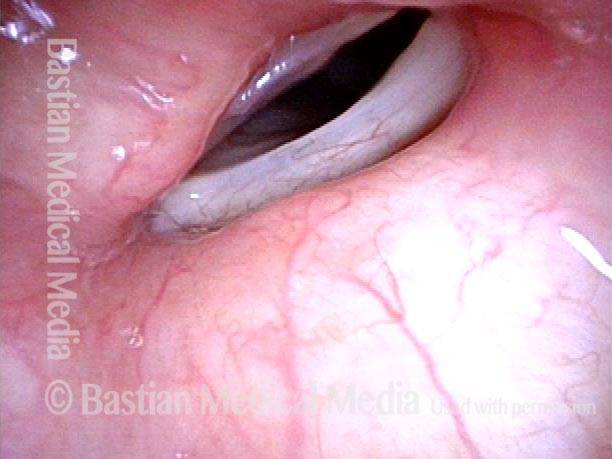

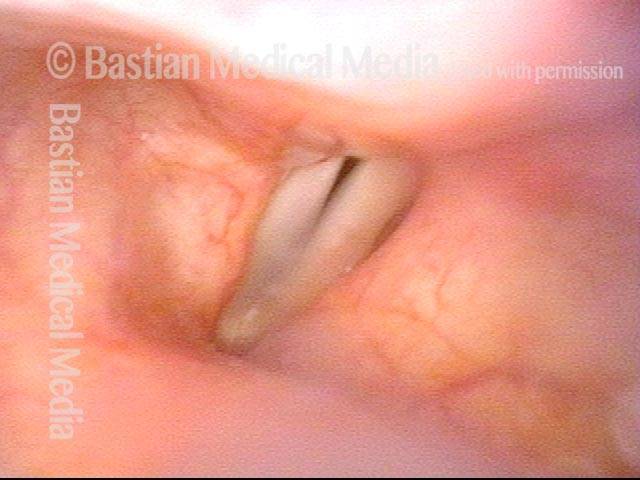

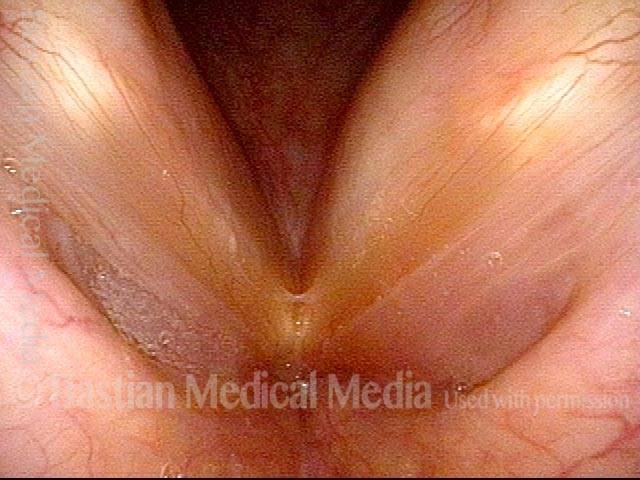

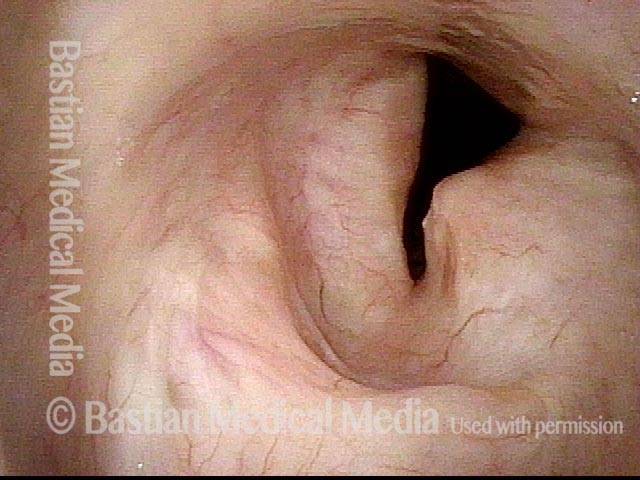

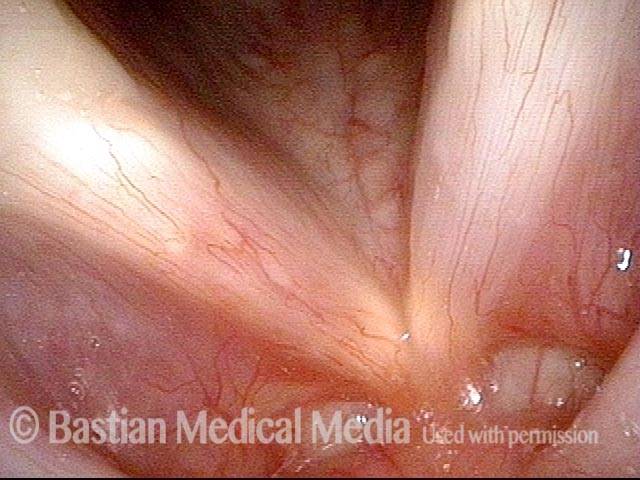

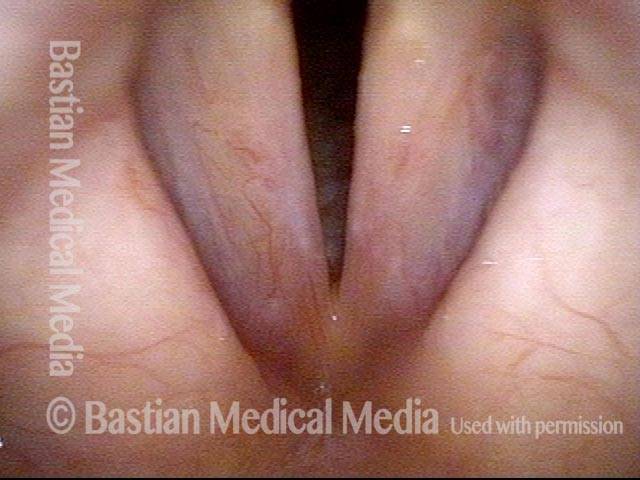

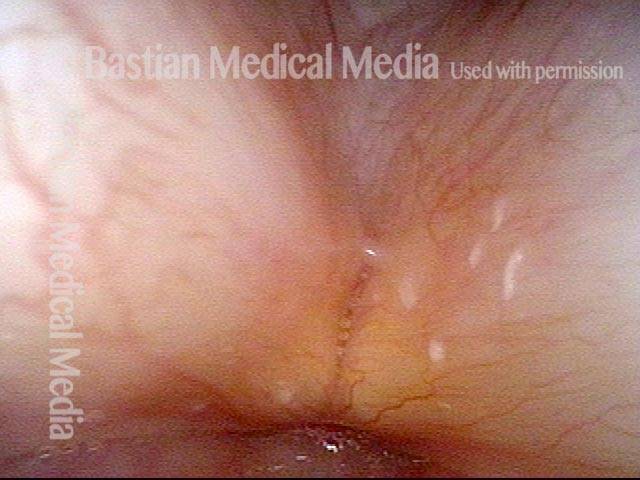

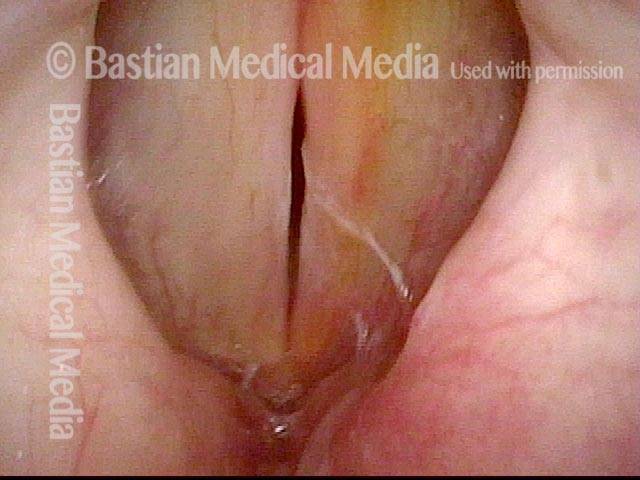

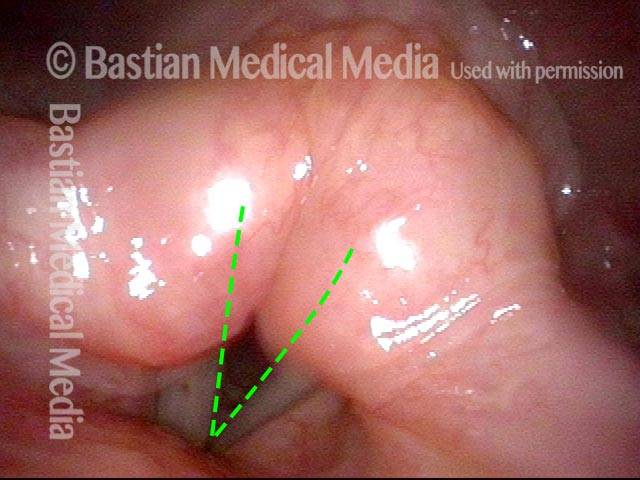

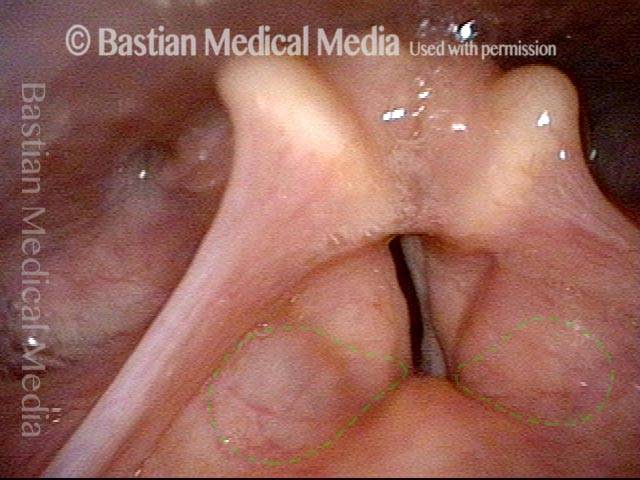

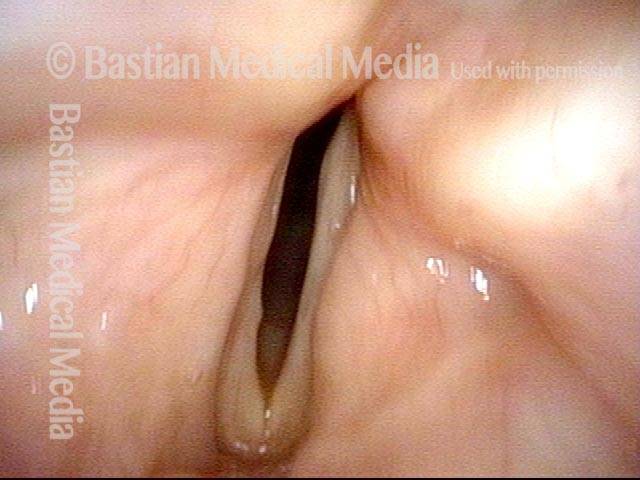

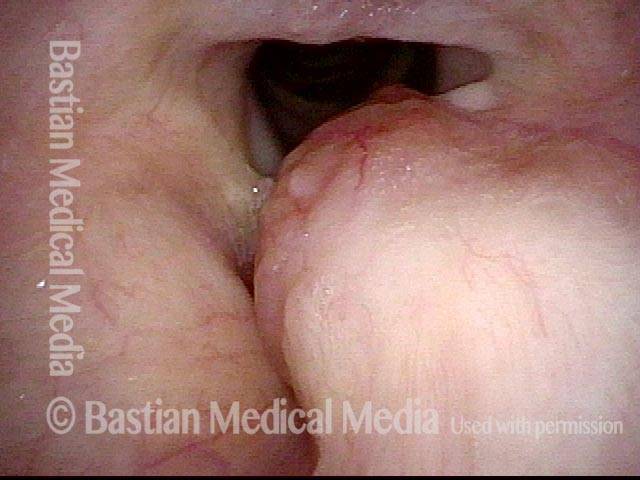

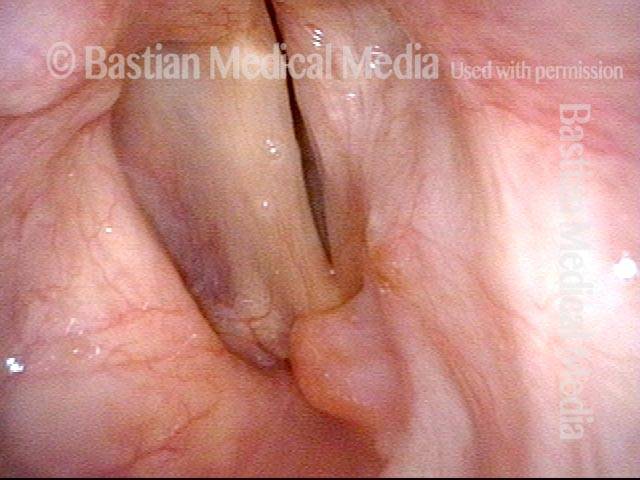

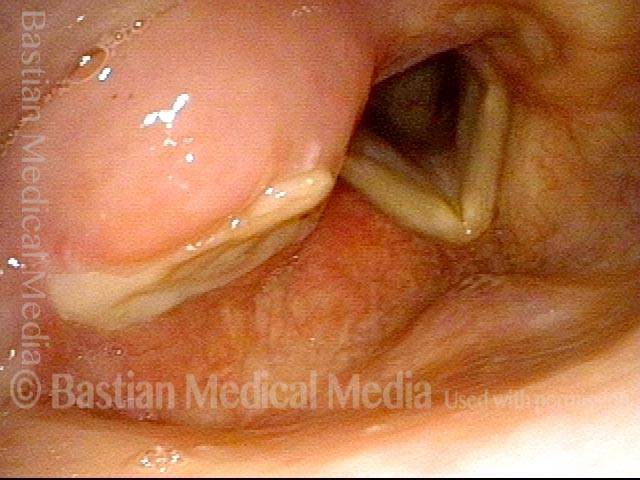

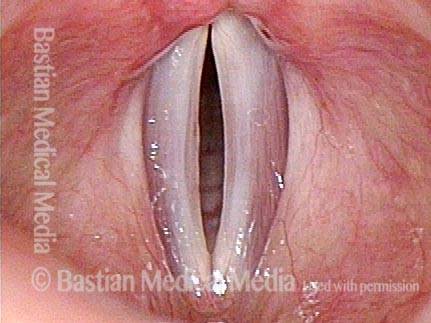

Vocal cord polyp (1 of 8)

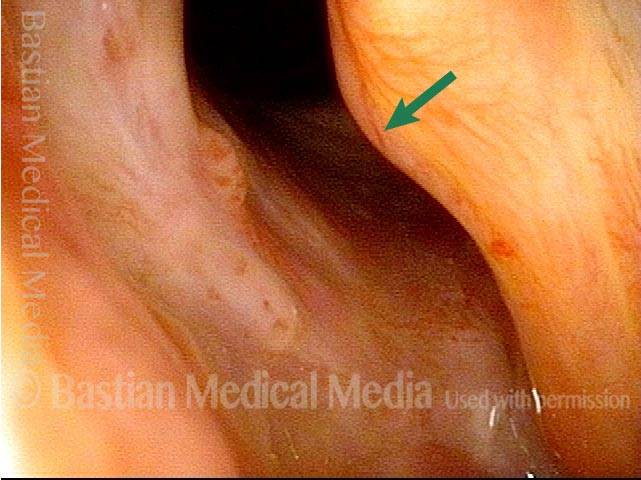

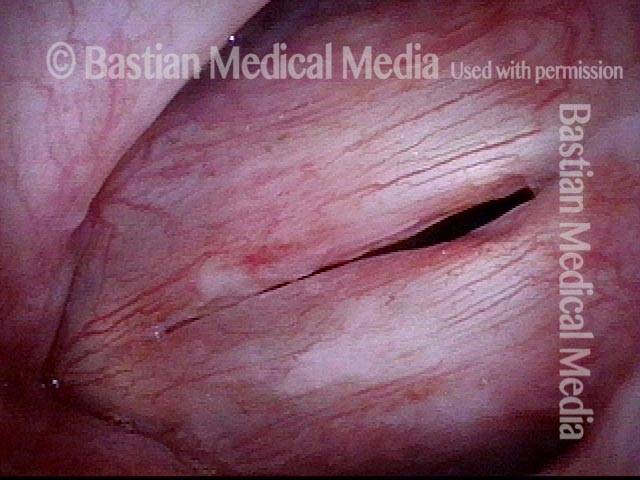

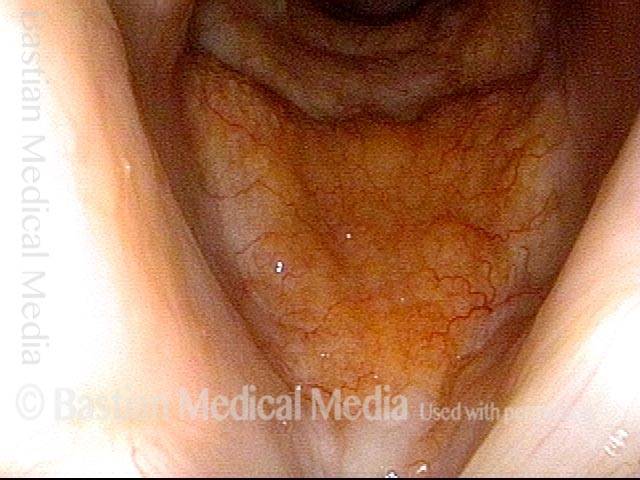

Musical theater actress with chronic hoarseness due to this right vocal cord polyp (left of photo), first identified a year earlier and unresponsive to speech therapy.

Vocal cord polyp (1 of 8)

Musical theater actress with chronic hoarseness due to this right vocal cord polyp (left of photo), first identified a year earlier and unresponsive to speech therapy.

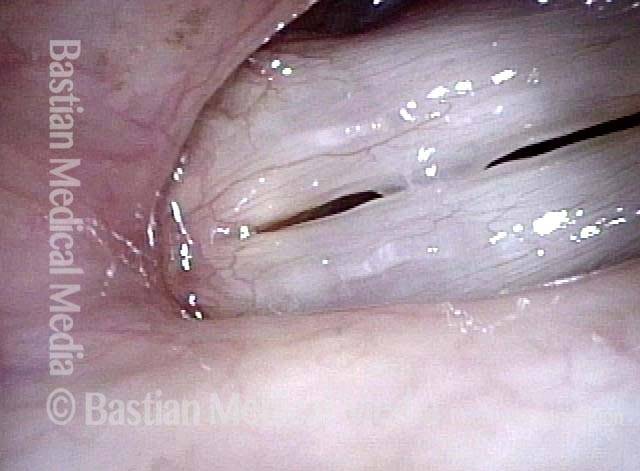

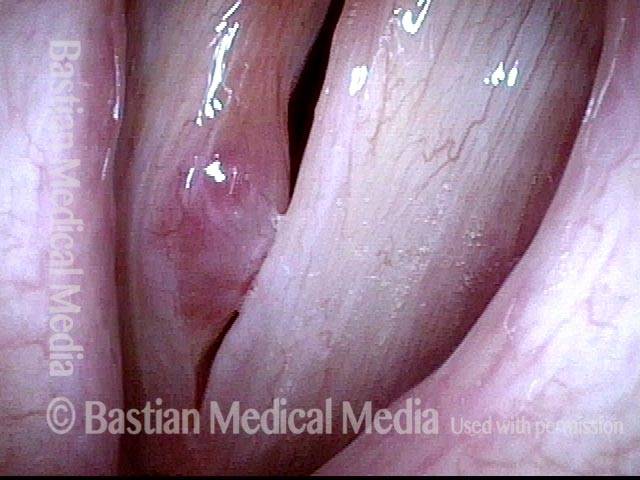

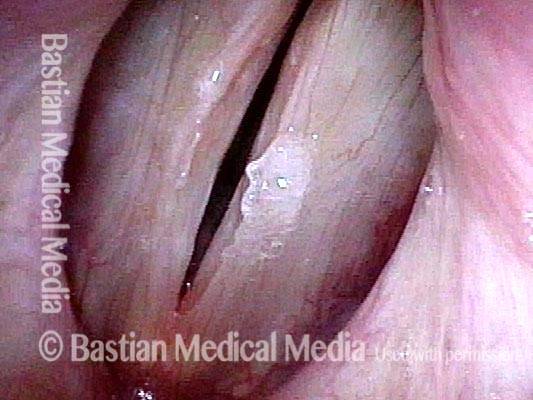

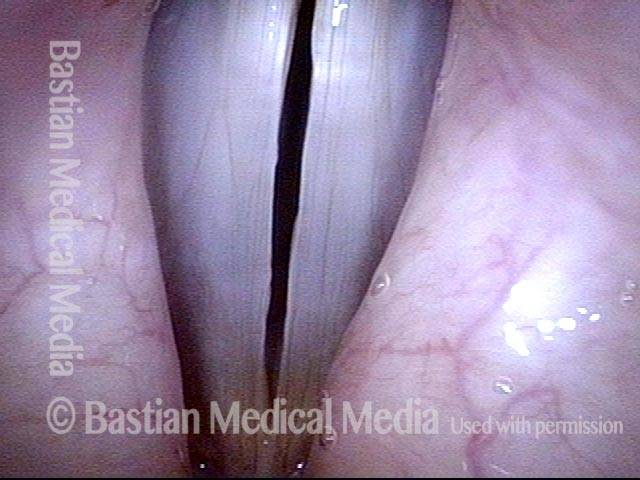

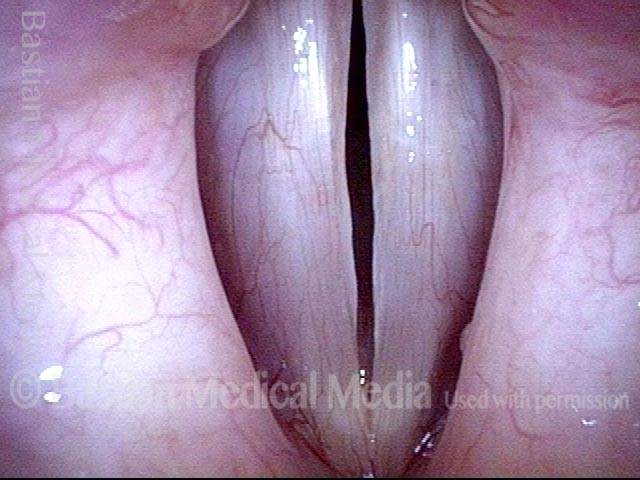

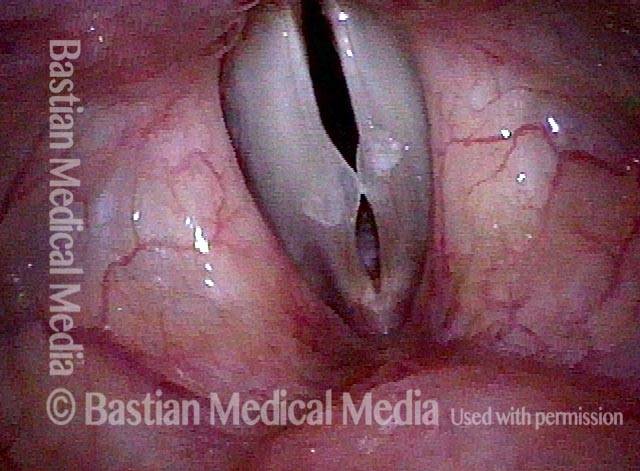

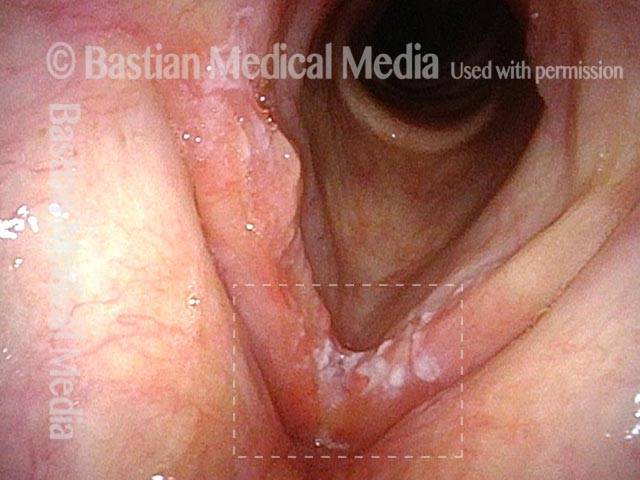

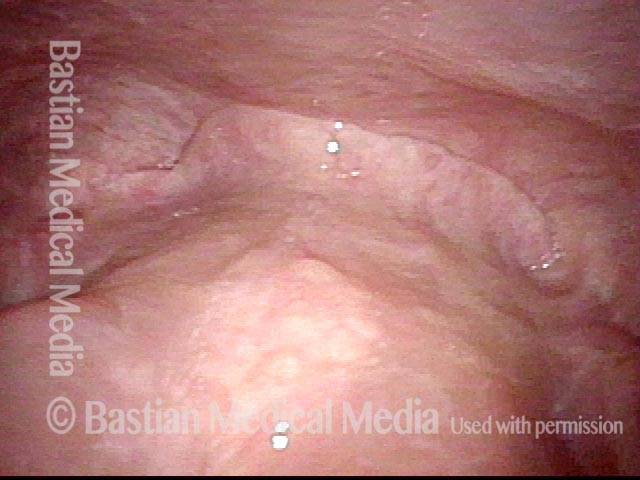

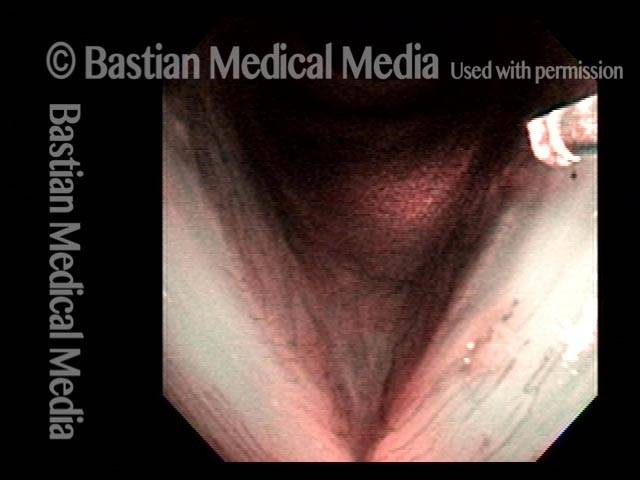

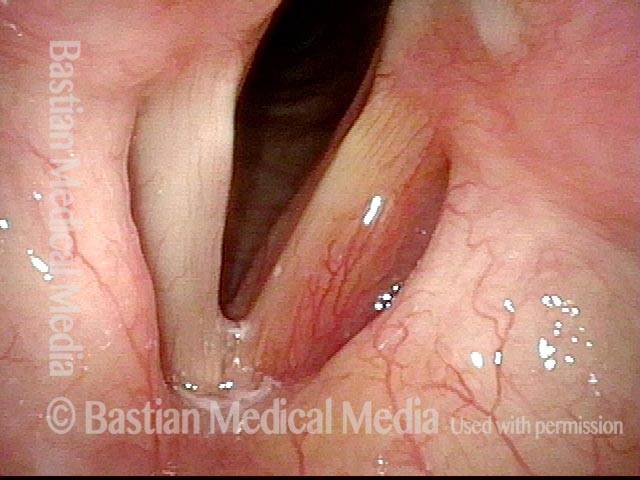

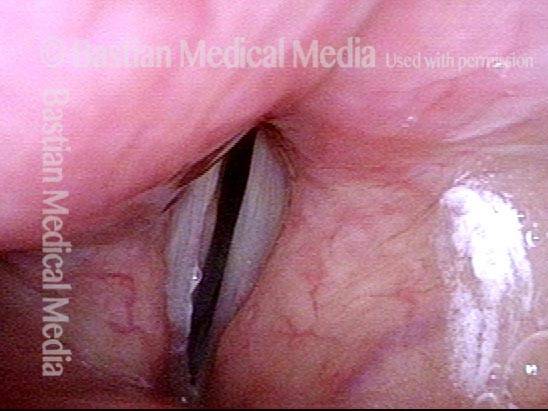

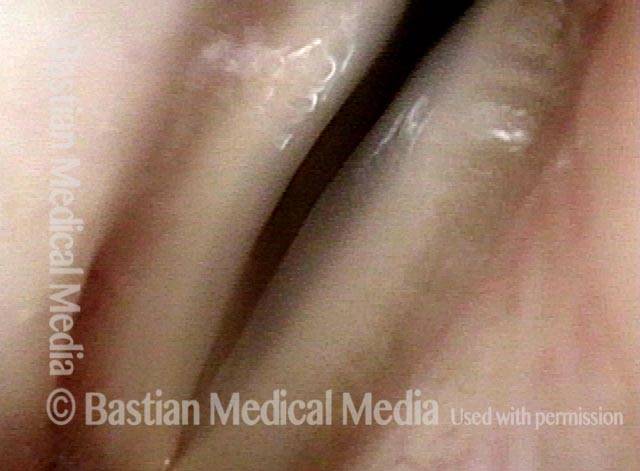

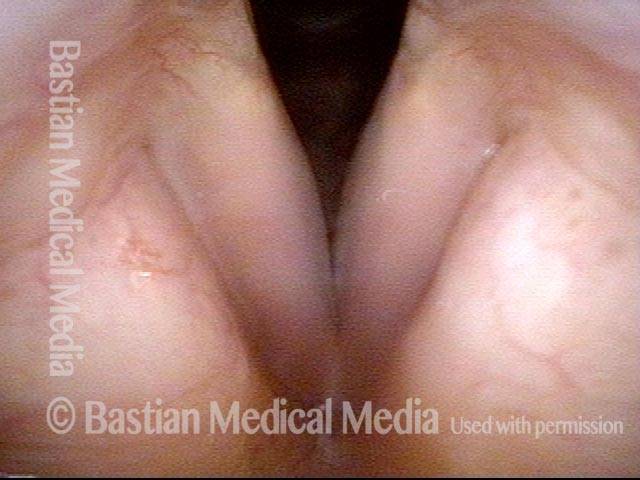

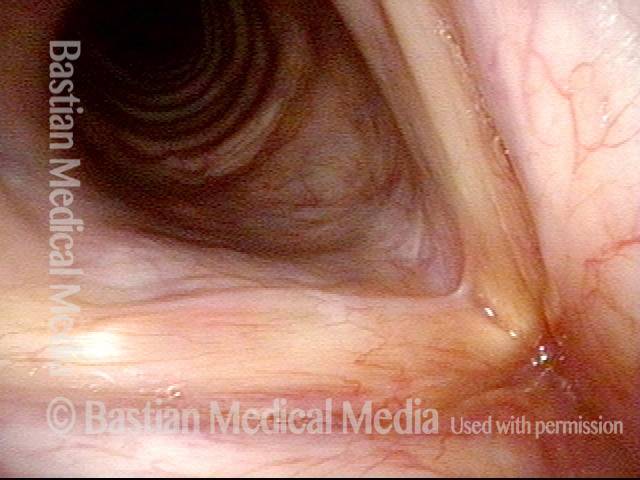

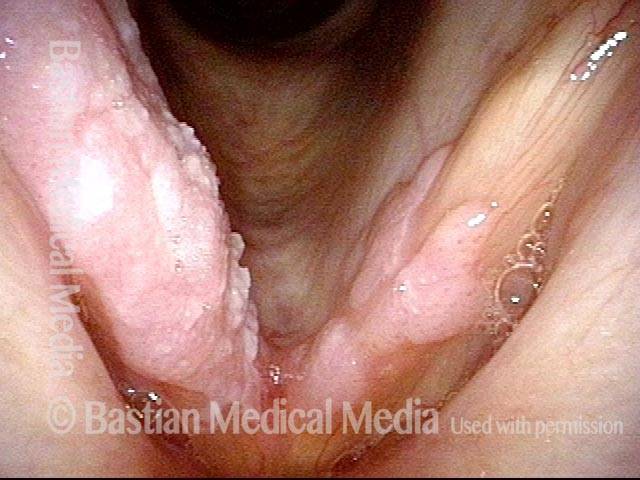

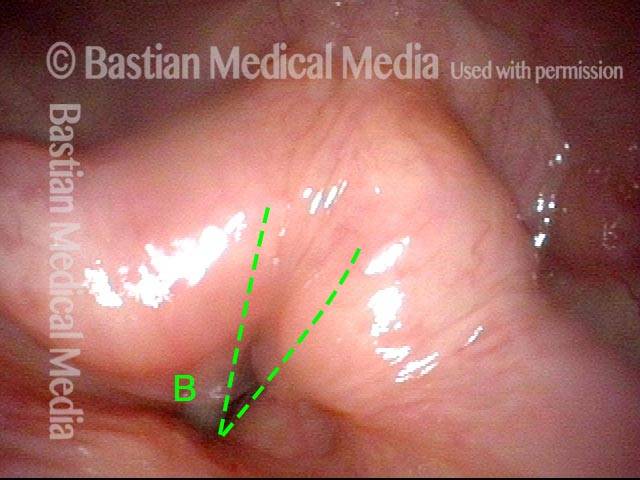

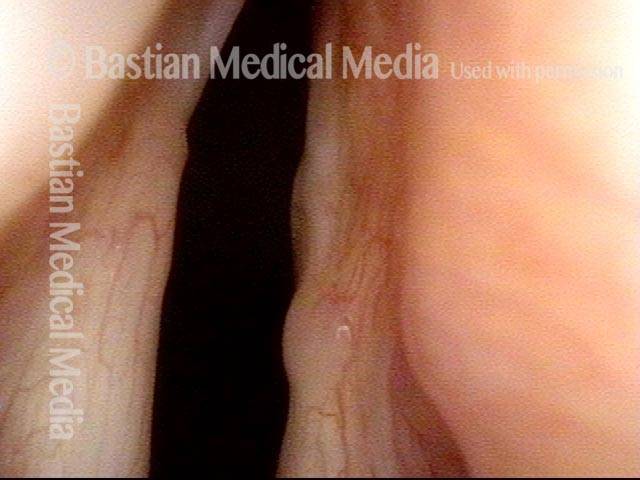

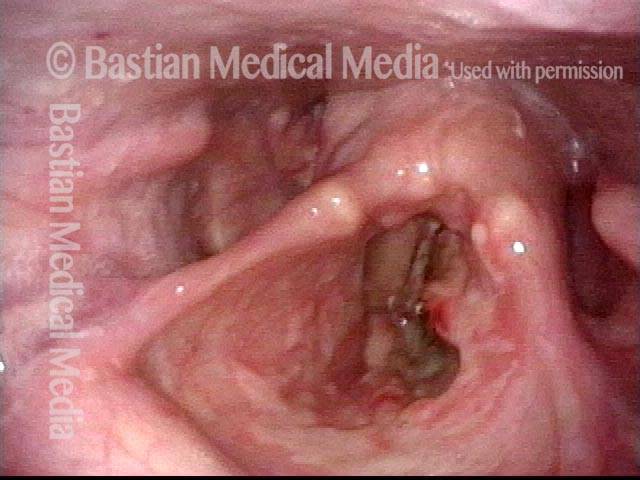

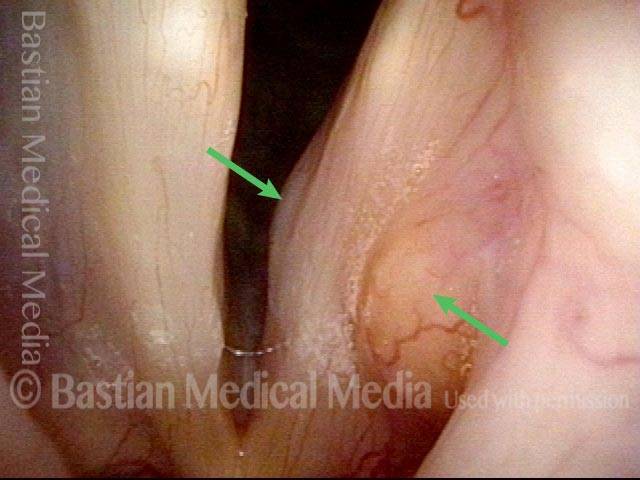

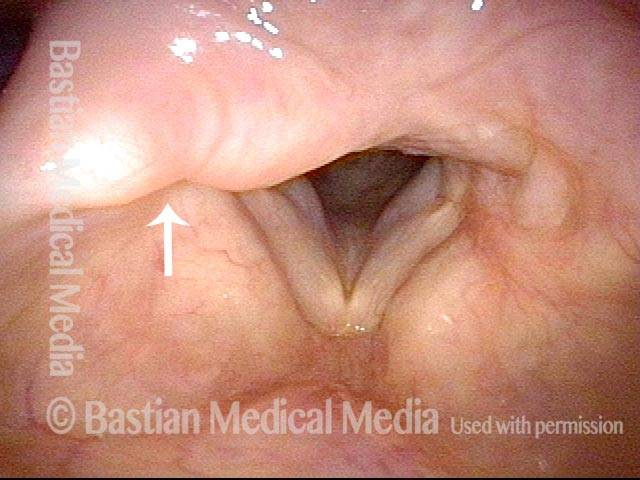

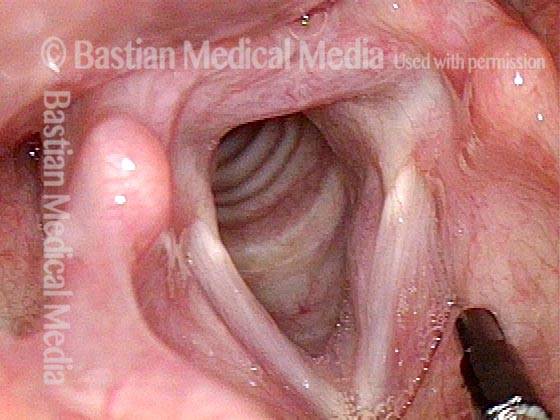

Closer view (2 of 8)

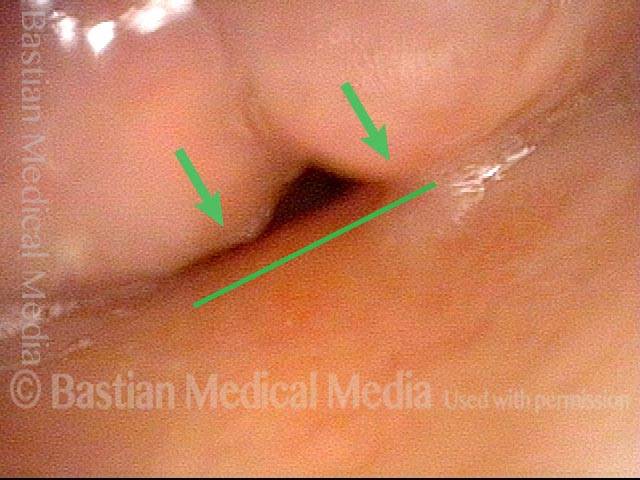

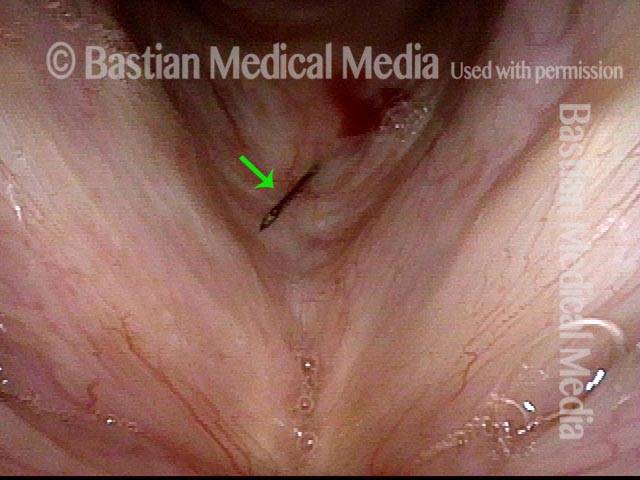

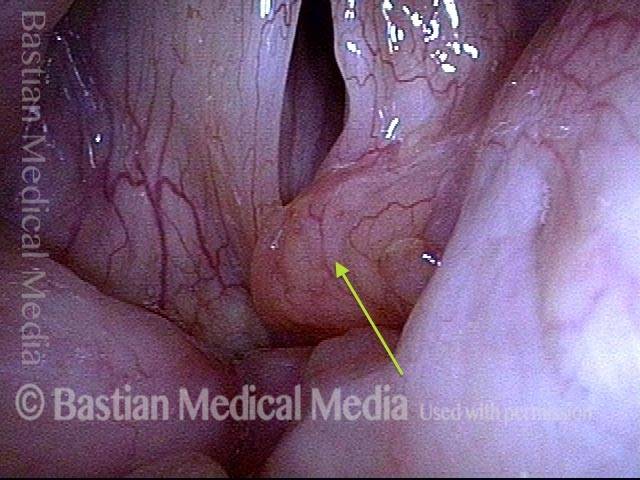

Magnified view shows small elevation of the left cord (right of photo) as well.

Closer view (2 of 8)

Magnified view shows small elevation of the left cord (right of photo) as well.

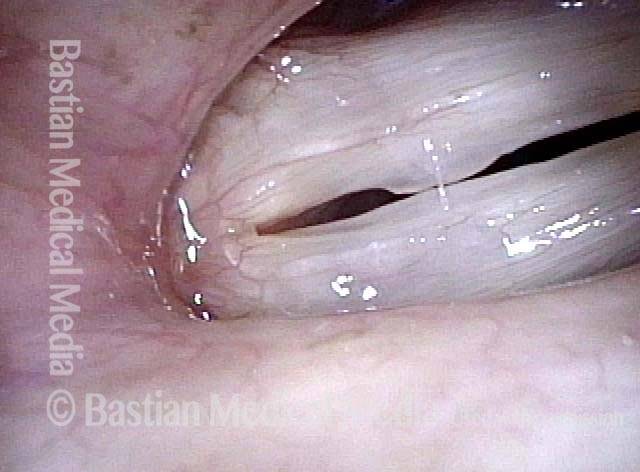

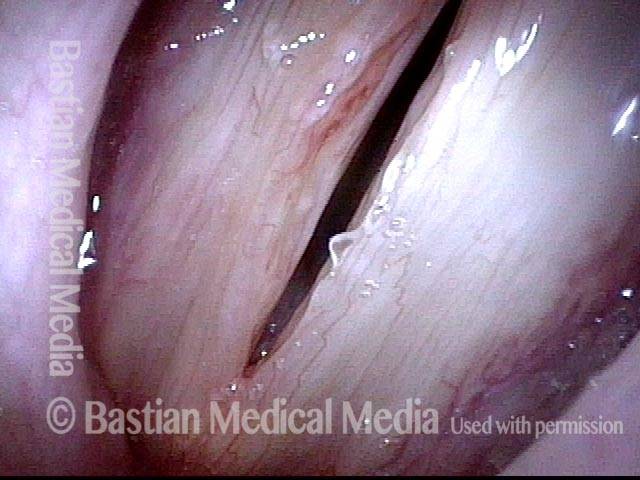

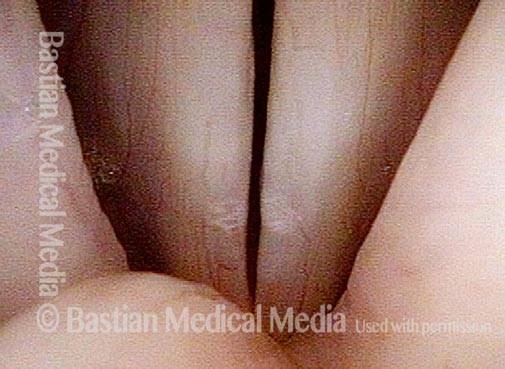

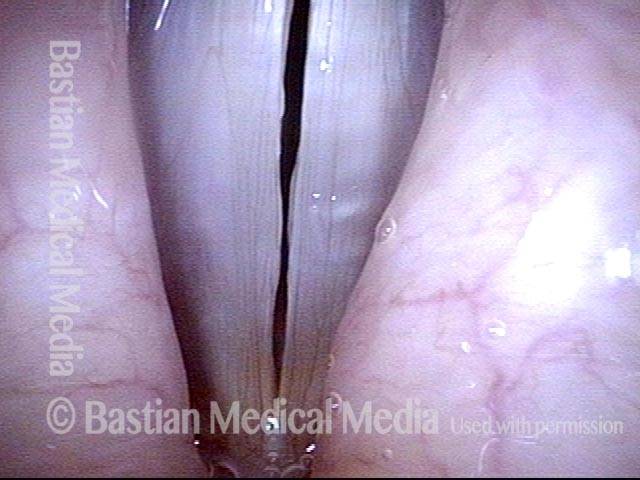

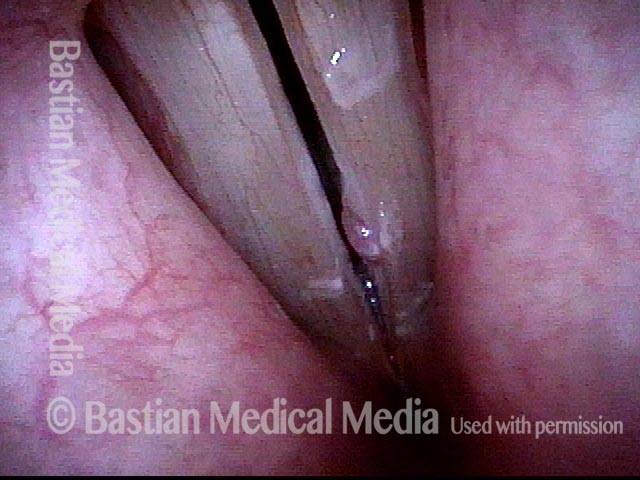

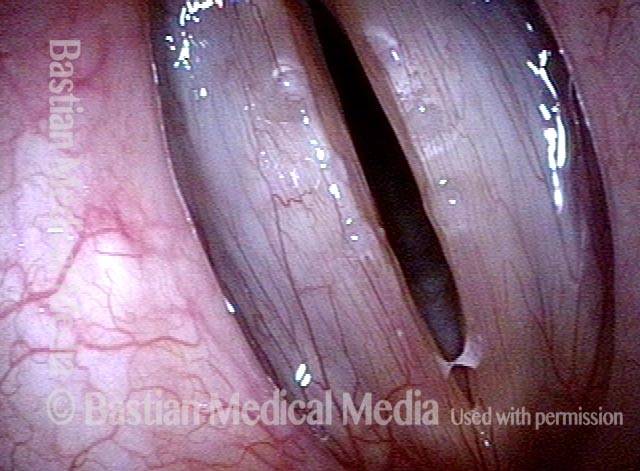

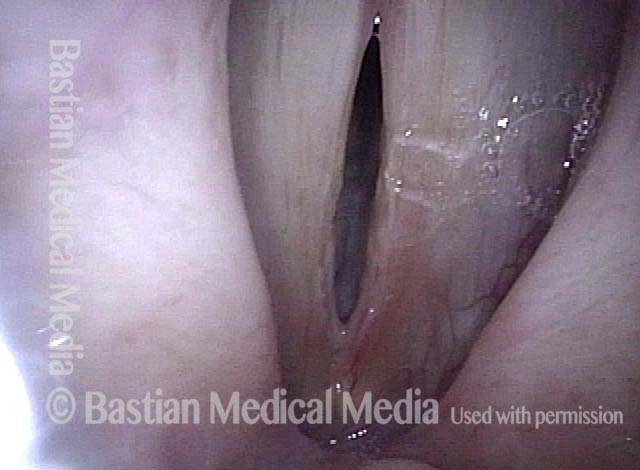

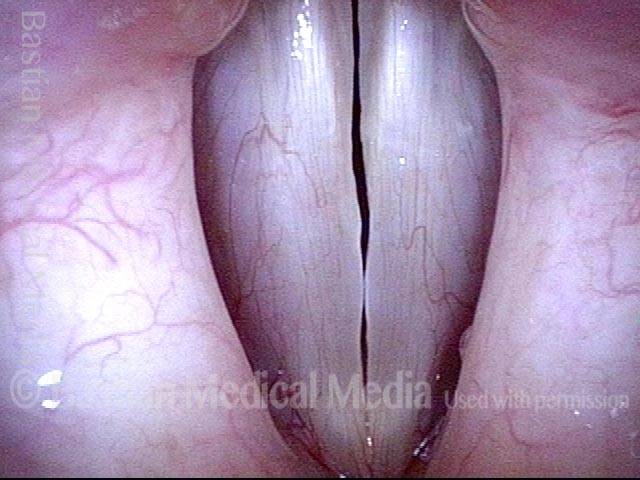

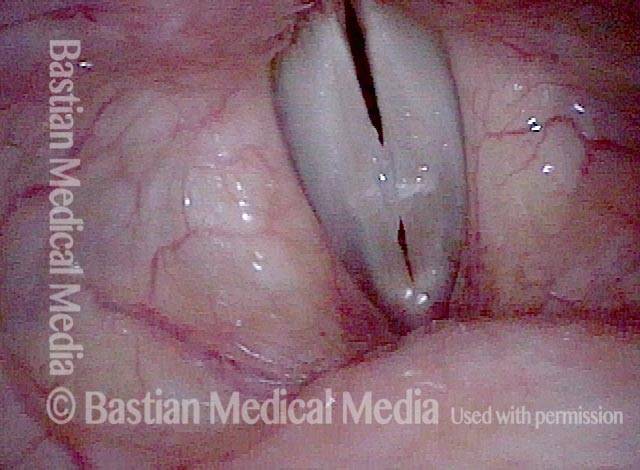

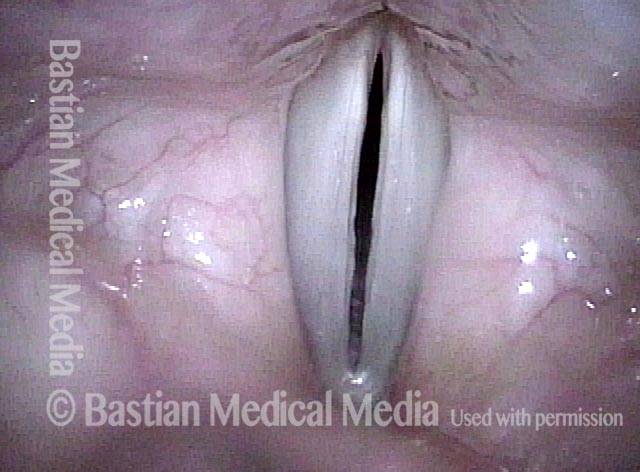

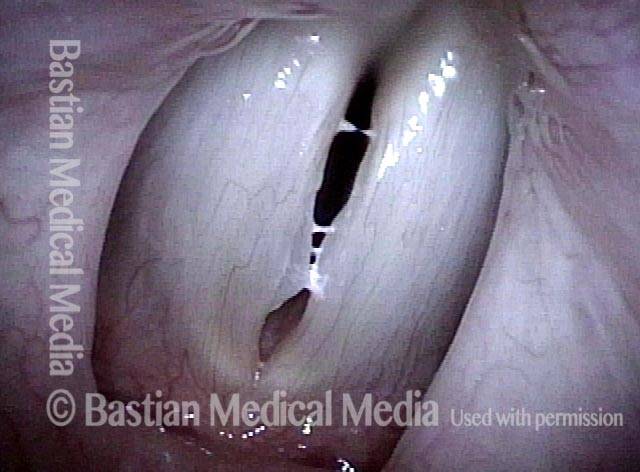

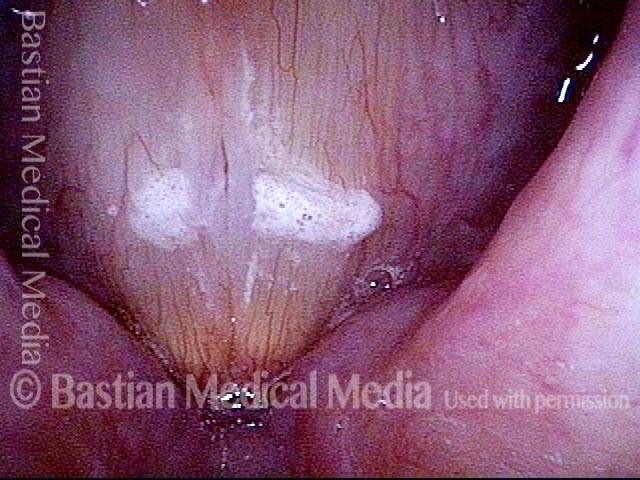

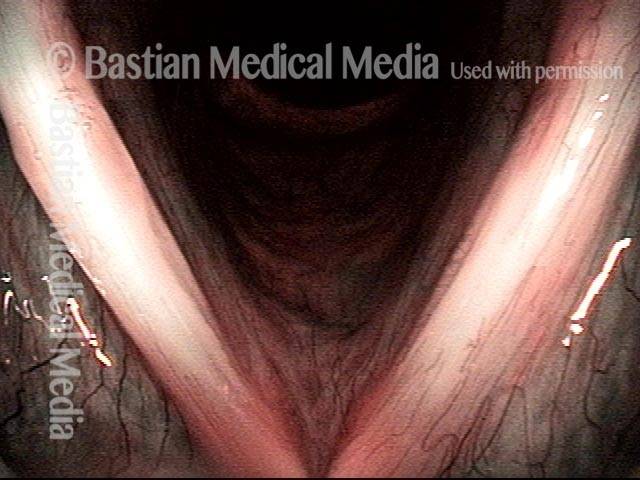

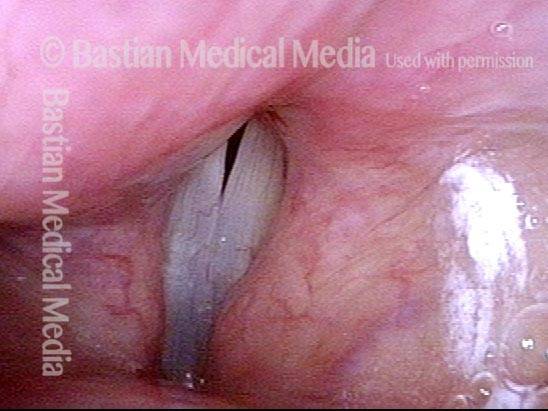

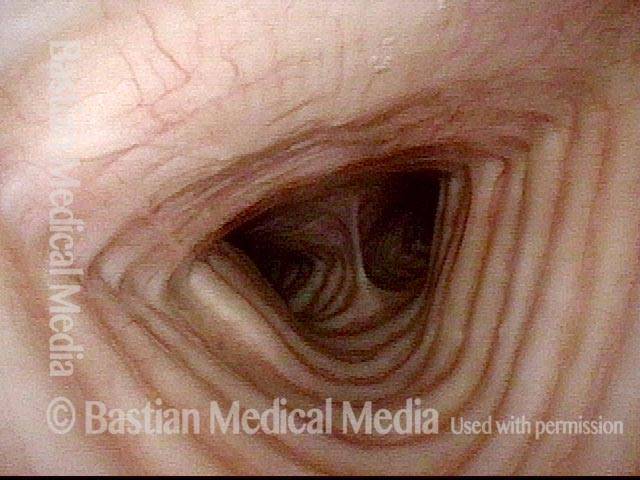

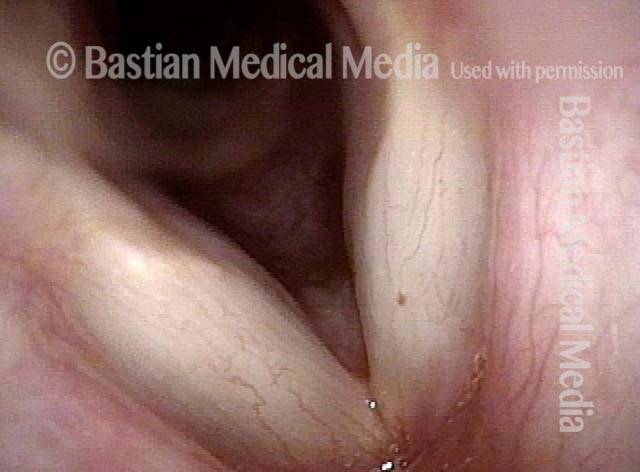

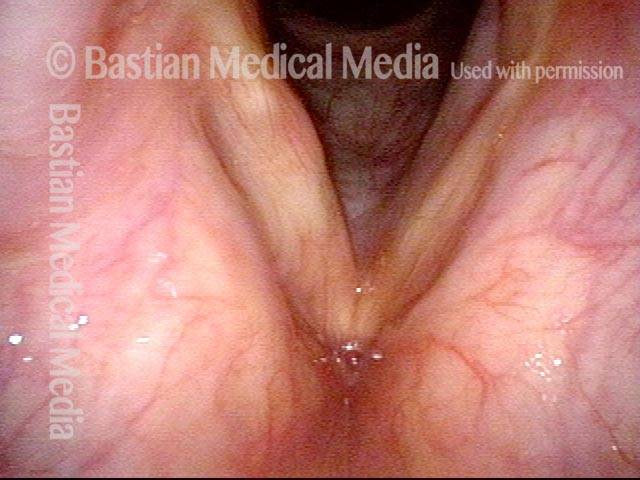

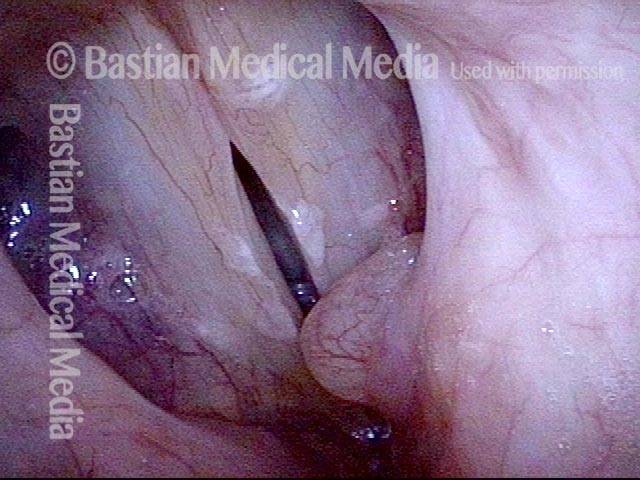

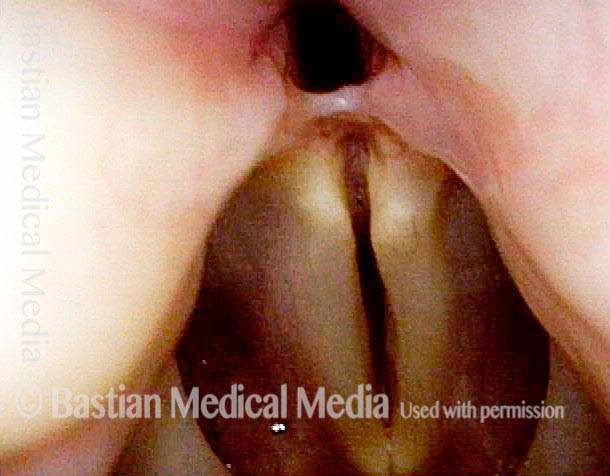

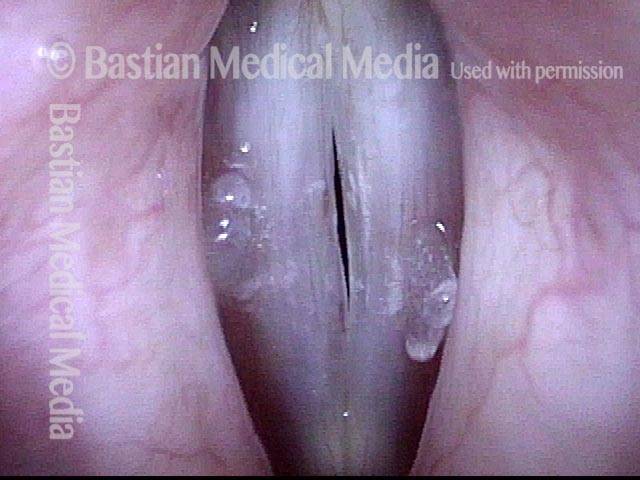

Closed phase (3 of 8)

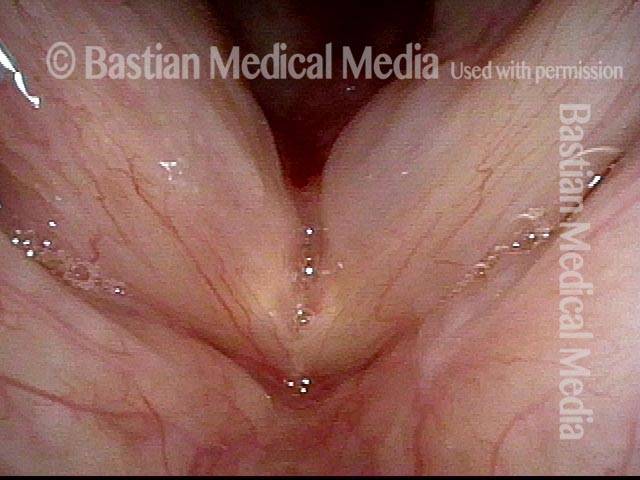

Closed phase of vibration (strobe light) at B flat 5 (932 Hz).

Closed phase (3 of 8)

Closed phase of vibration (strobe light) at B flat 5 (932 Hz).

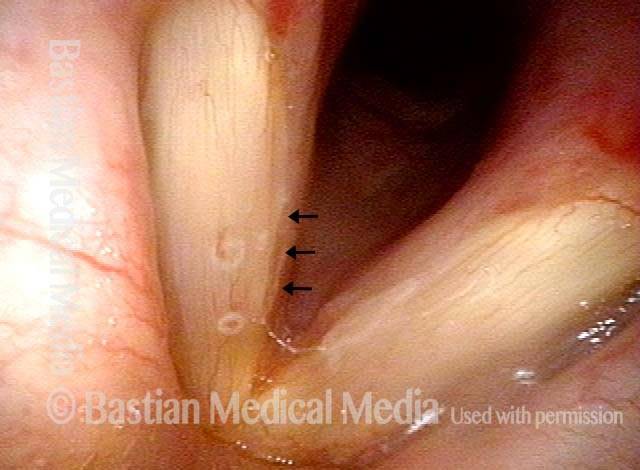

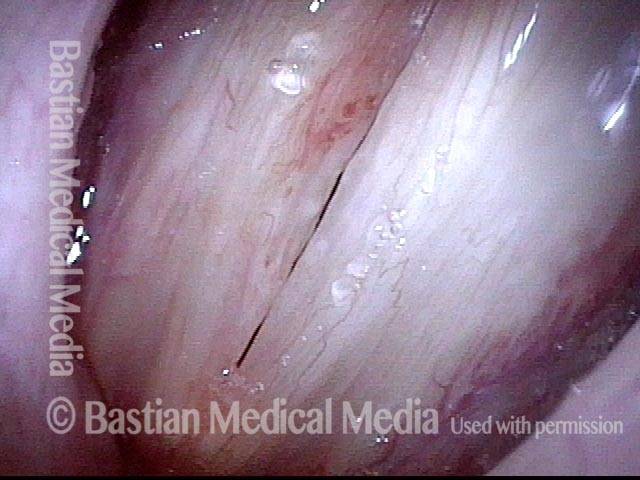

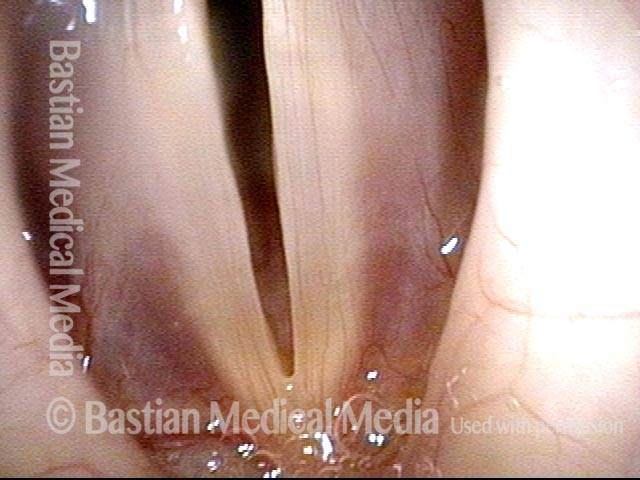

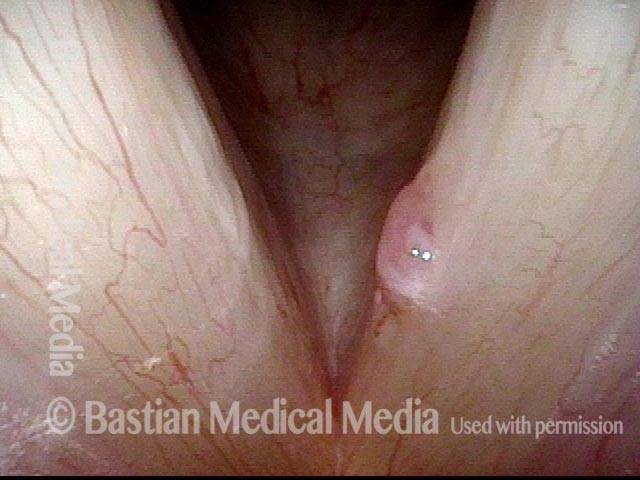

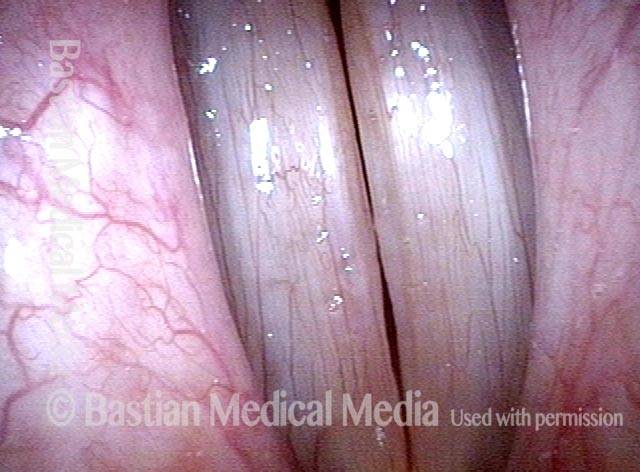

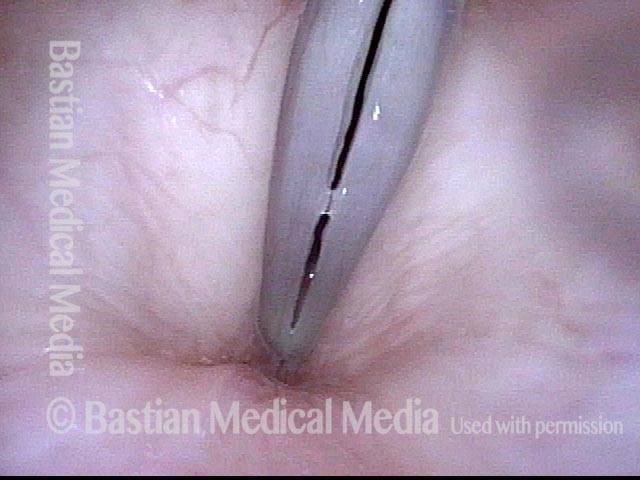

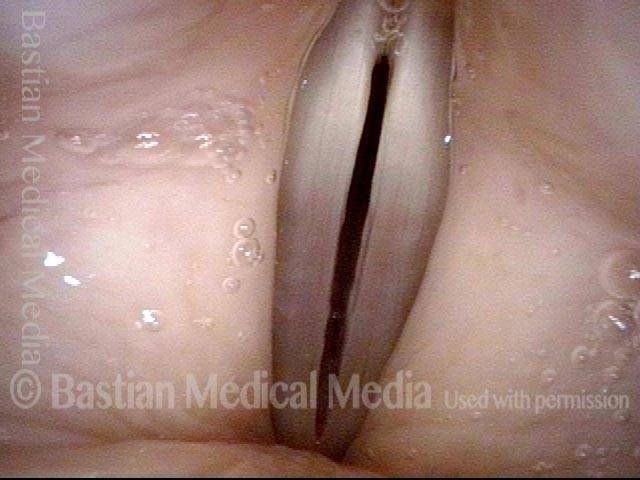

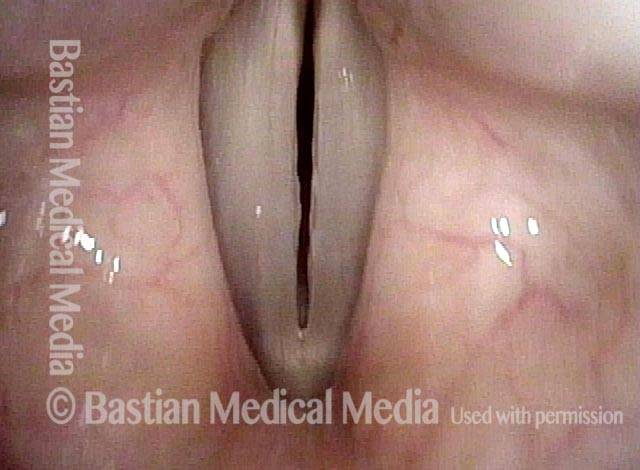

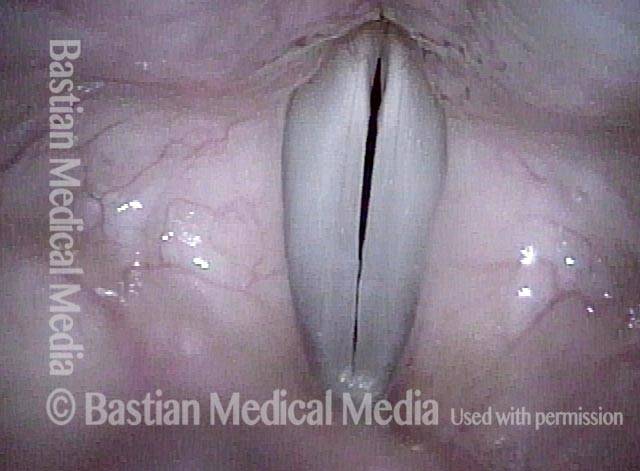

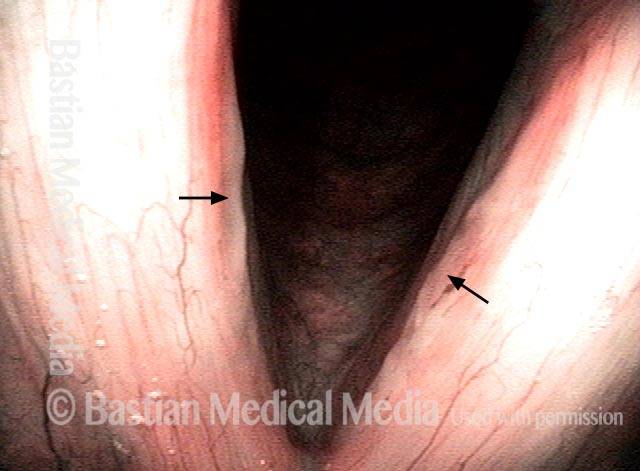

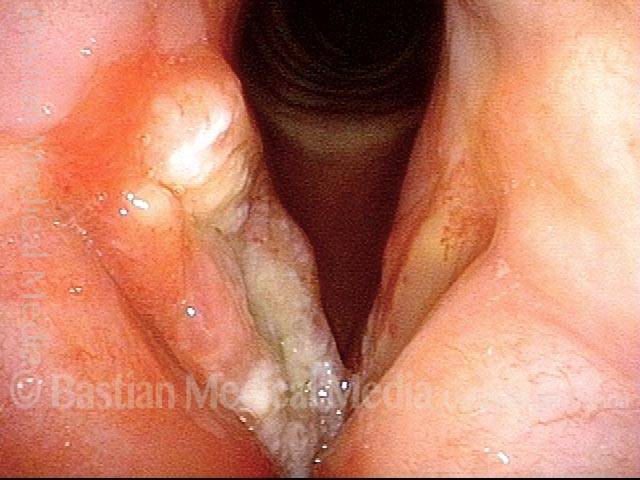

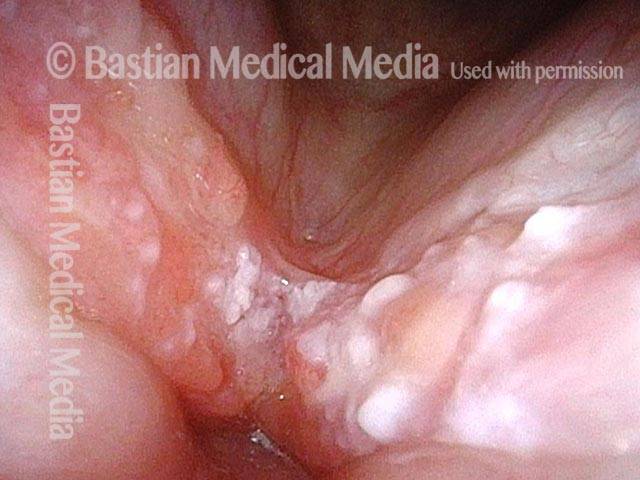

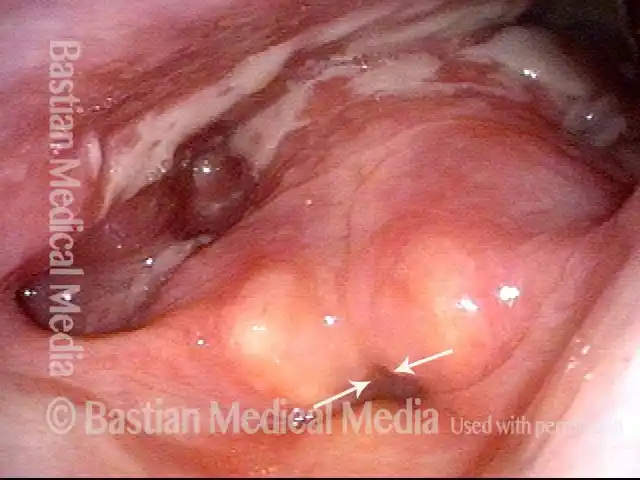

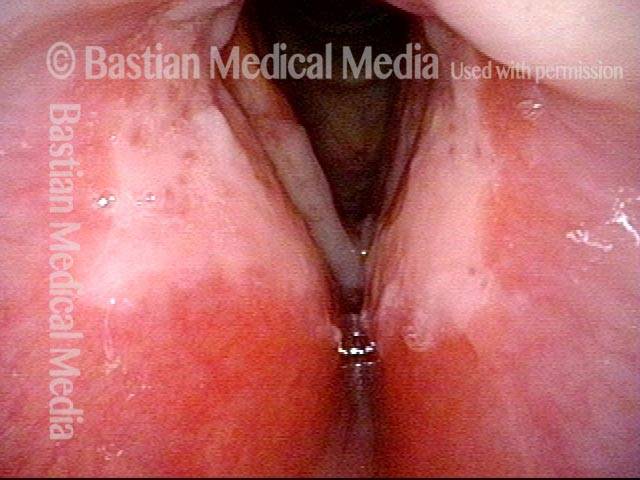

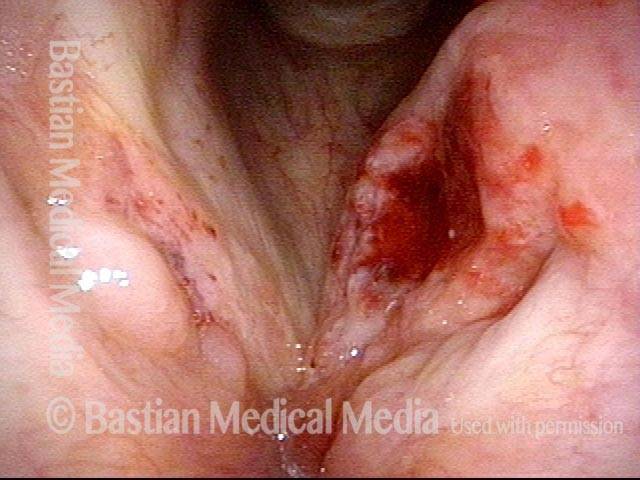

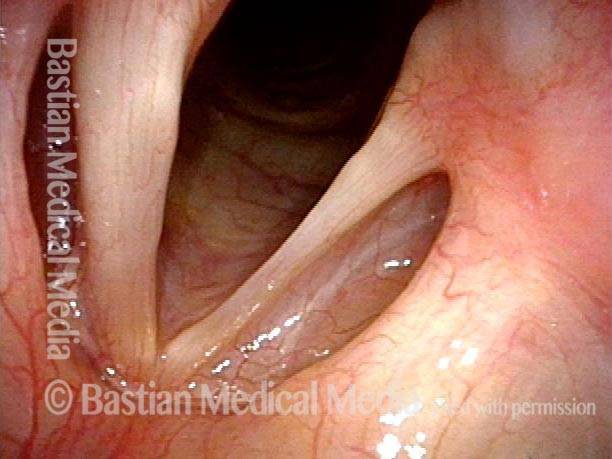

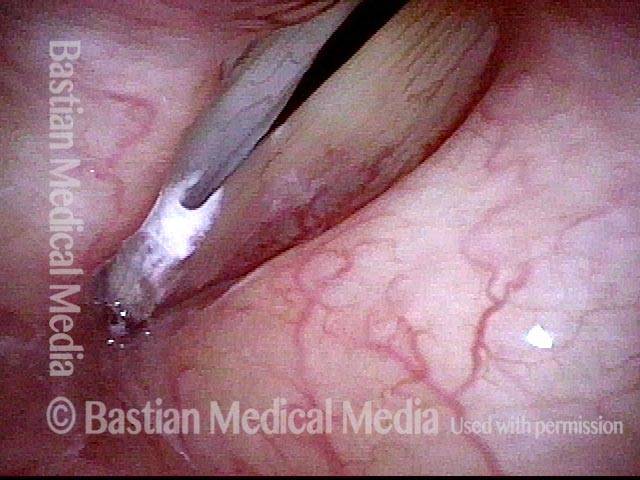

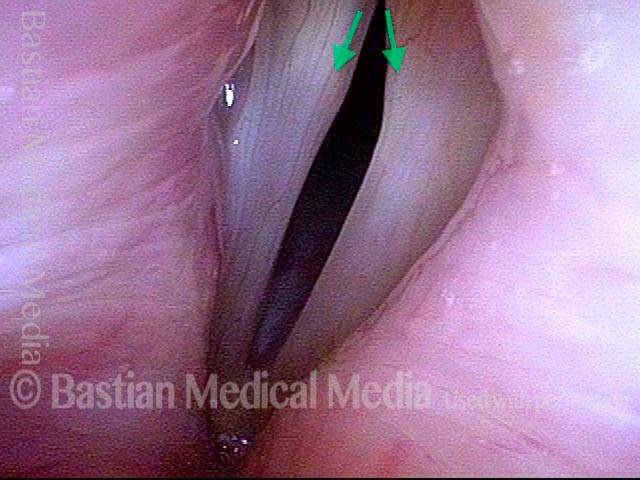

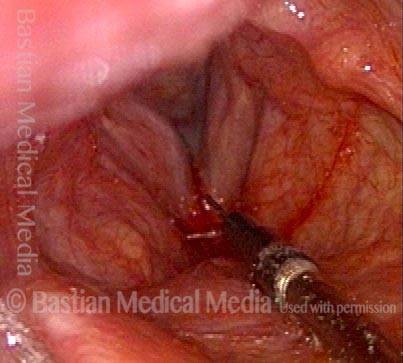

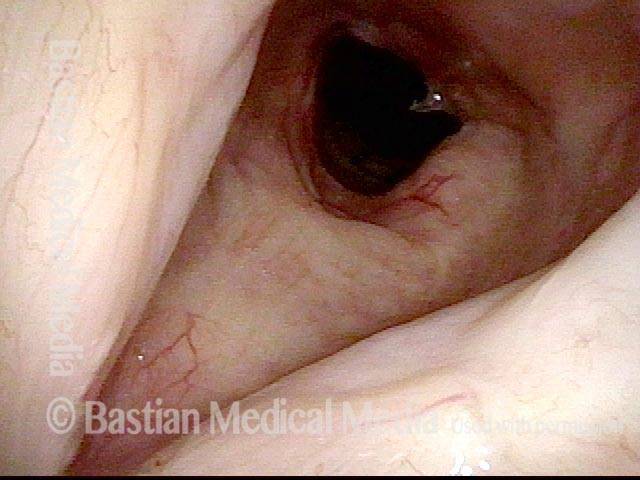

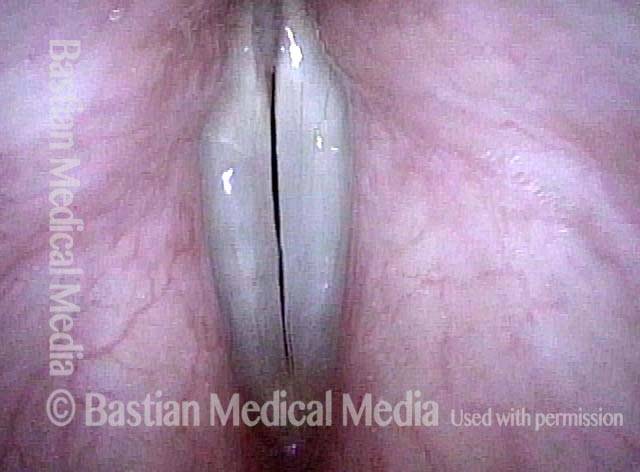

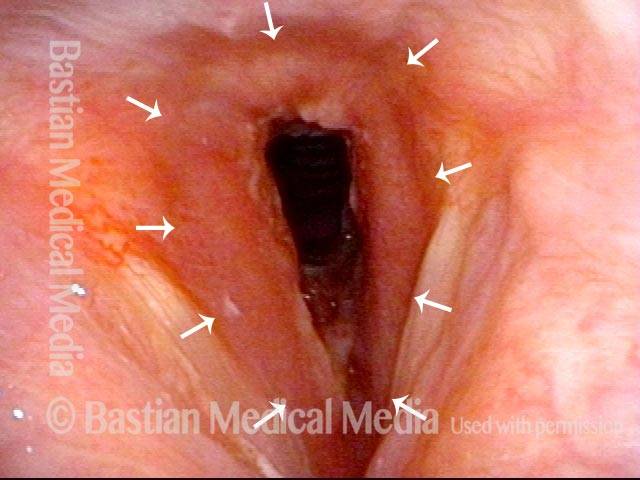

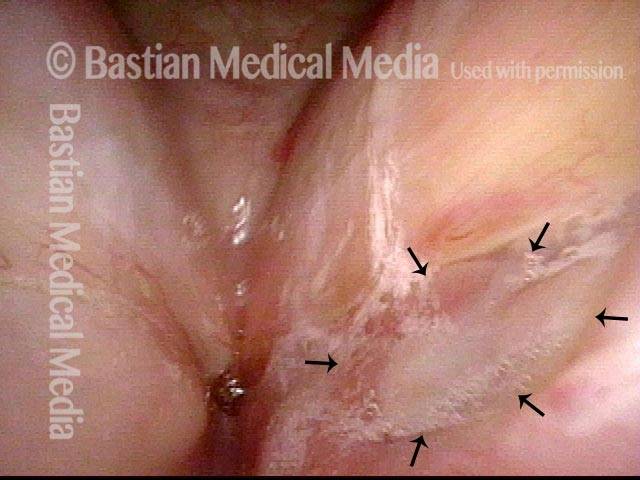

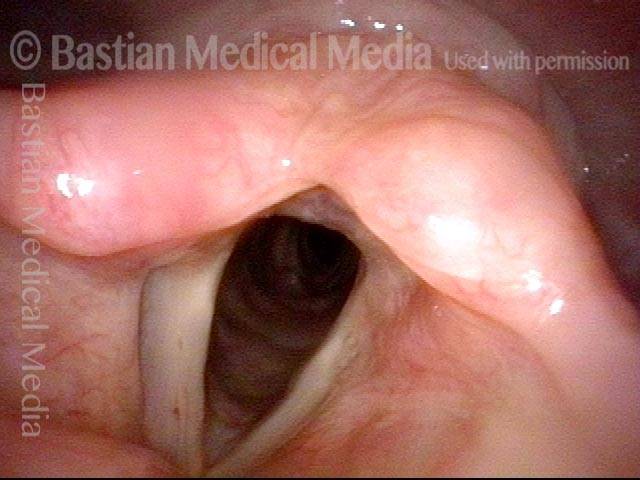

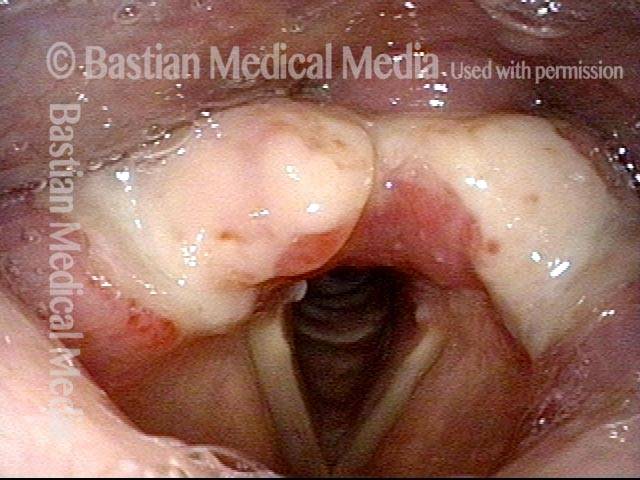

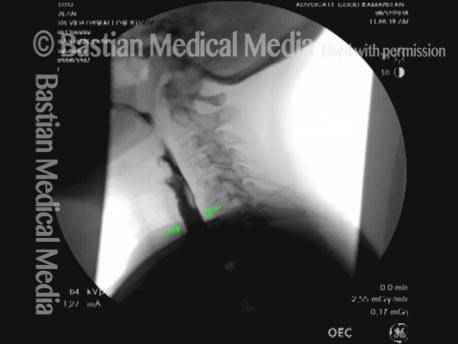

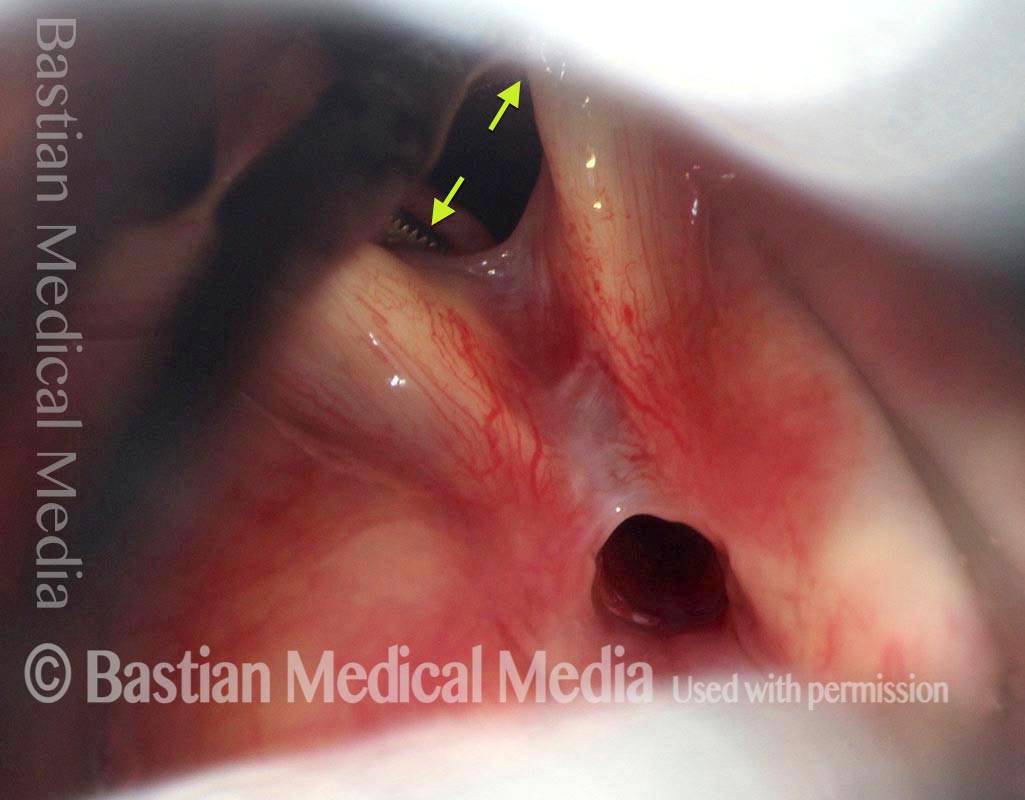

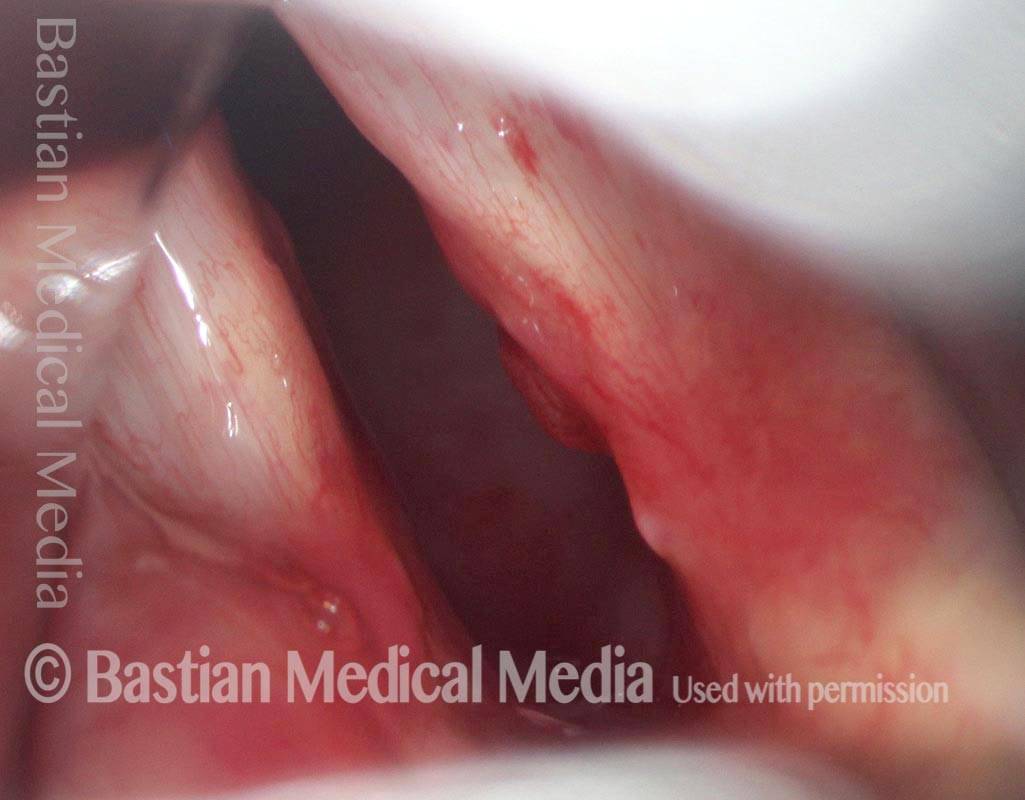

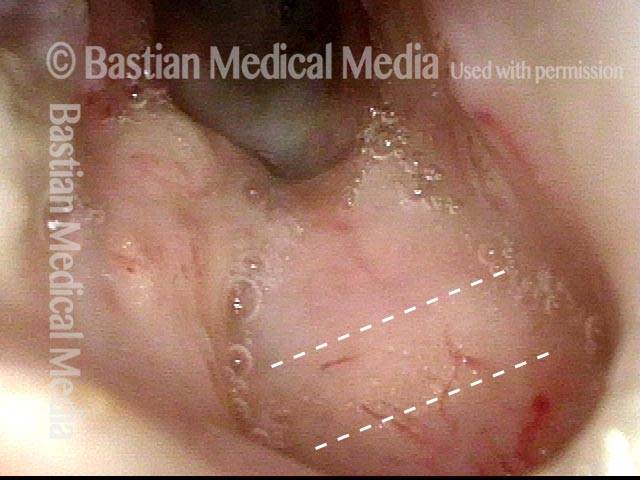

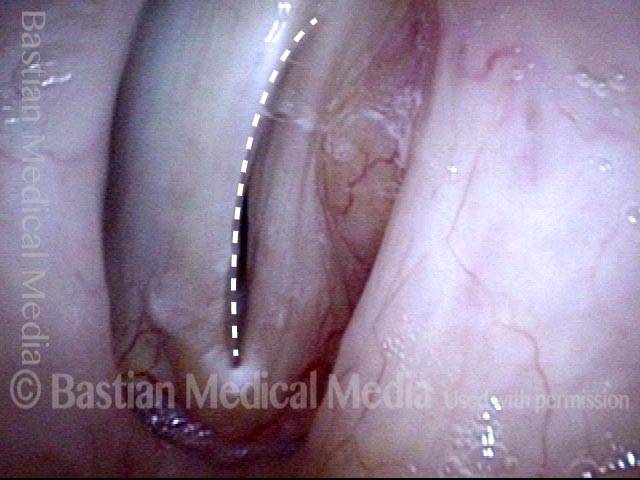

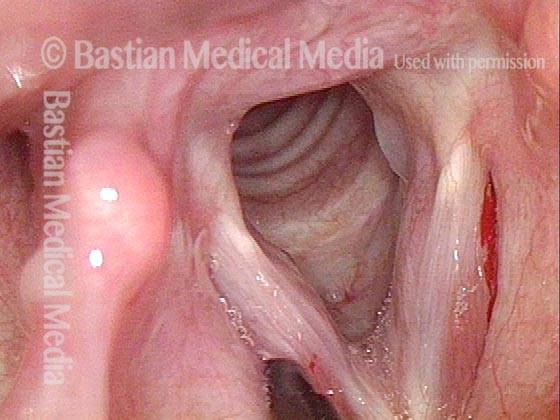

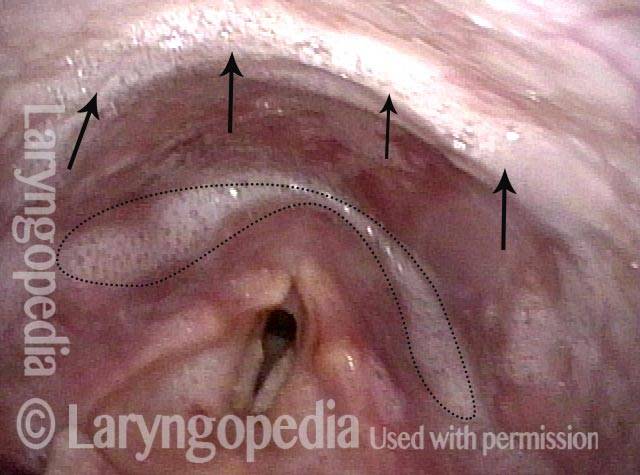

24 hours post surgery (5 of 8)

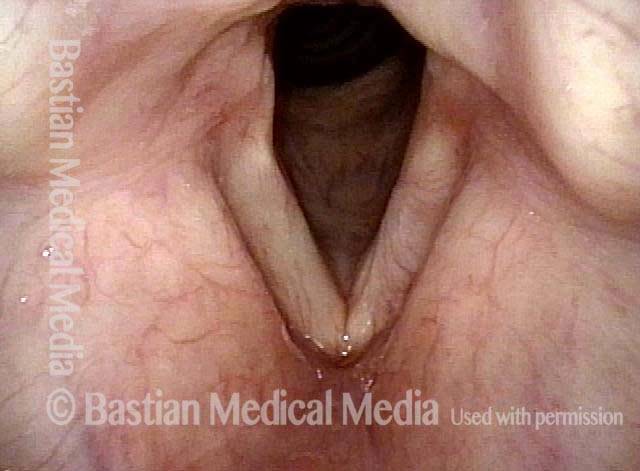

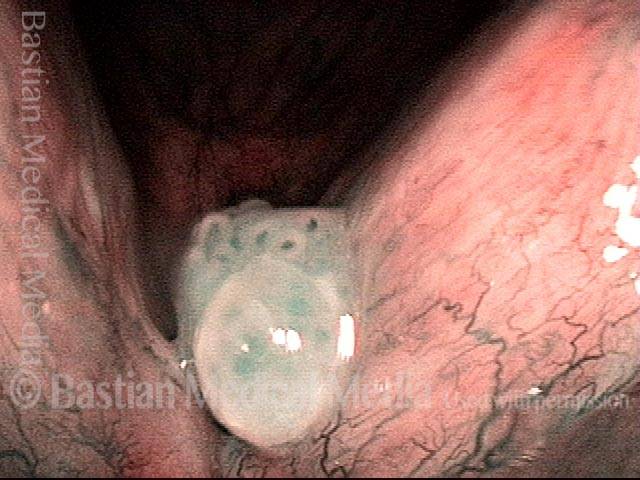

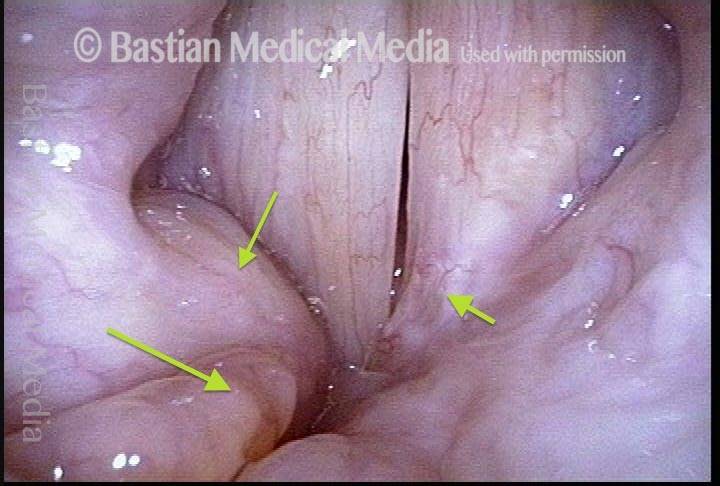

The next day, only a few hours after surgical removal. Note slight bruising from the endotracheal tube (long arrows), and small dots where a laser impact was used to interrupt flow in a prominent capillary (short arrows).

24 hours post surgery (5 of 8)

The next day, only a few hours after surgical removal. Note slight bruising from the endotracheal tube (long arrows), and small dots where a laser impact was used to interrupt flow in a prominent capillary (short arrows).

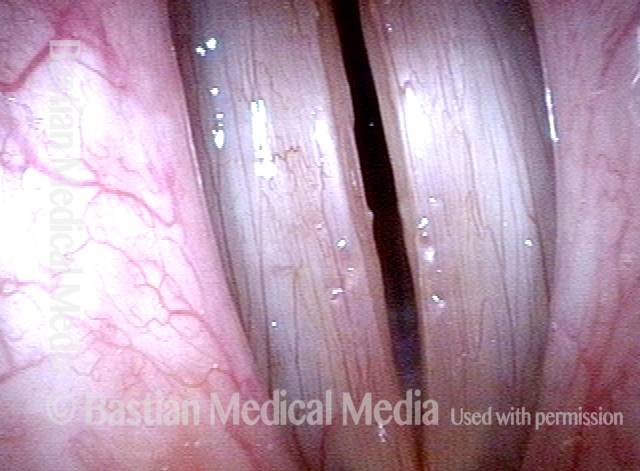

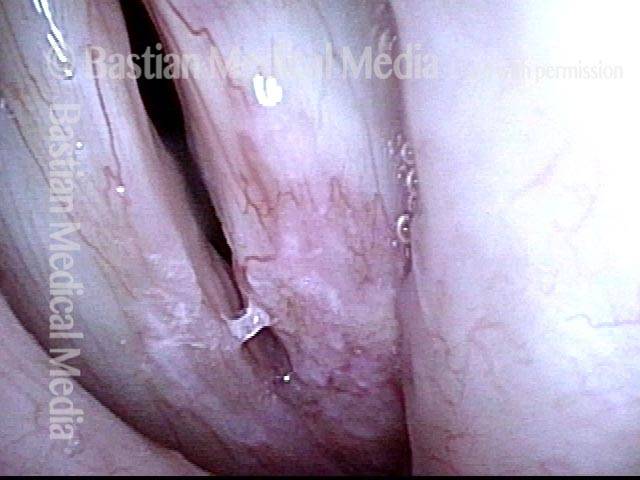

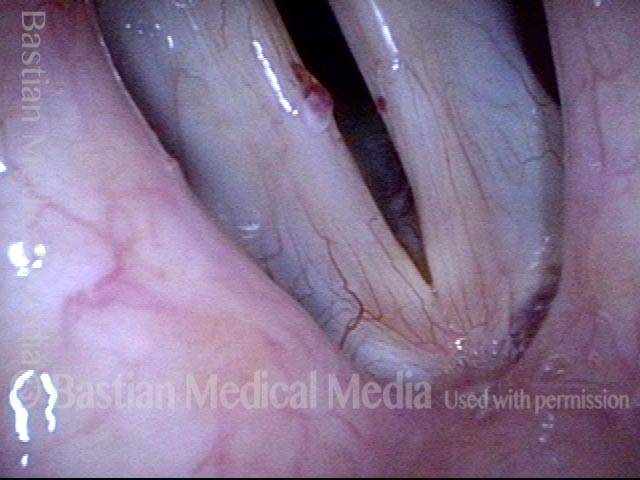

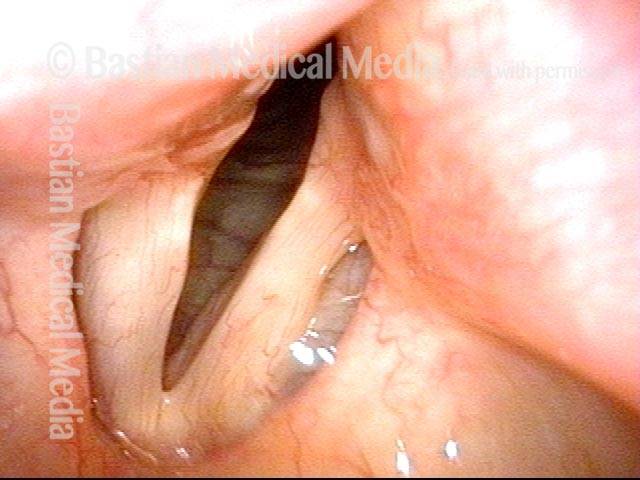

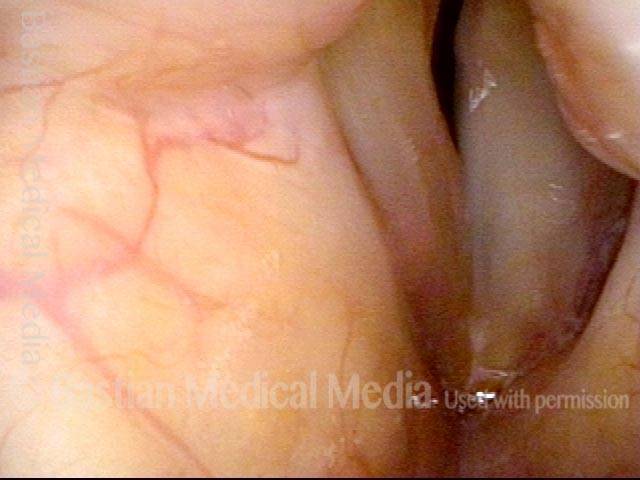

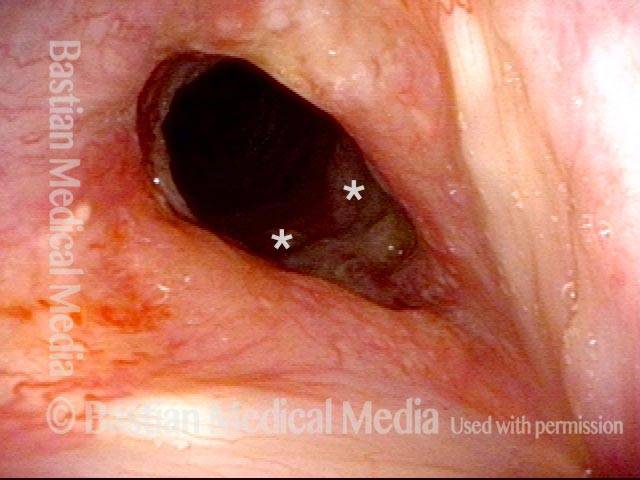

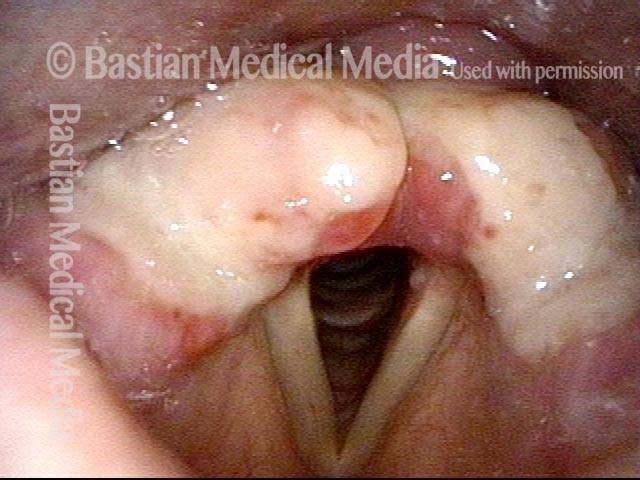

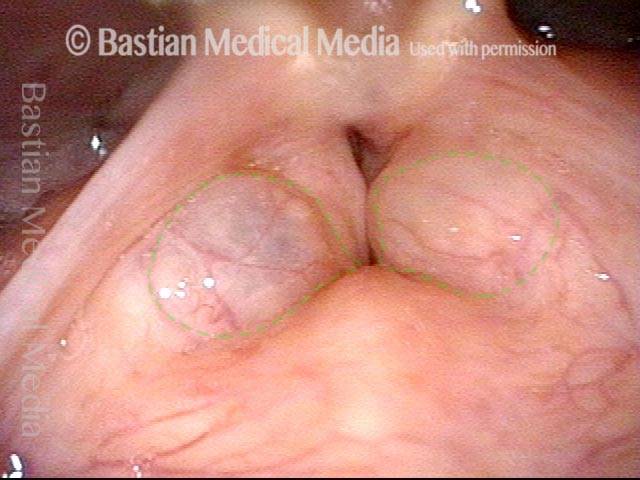

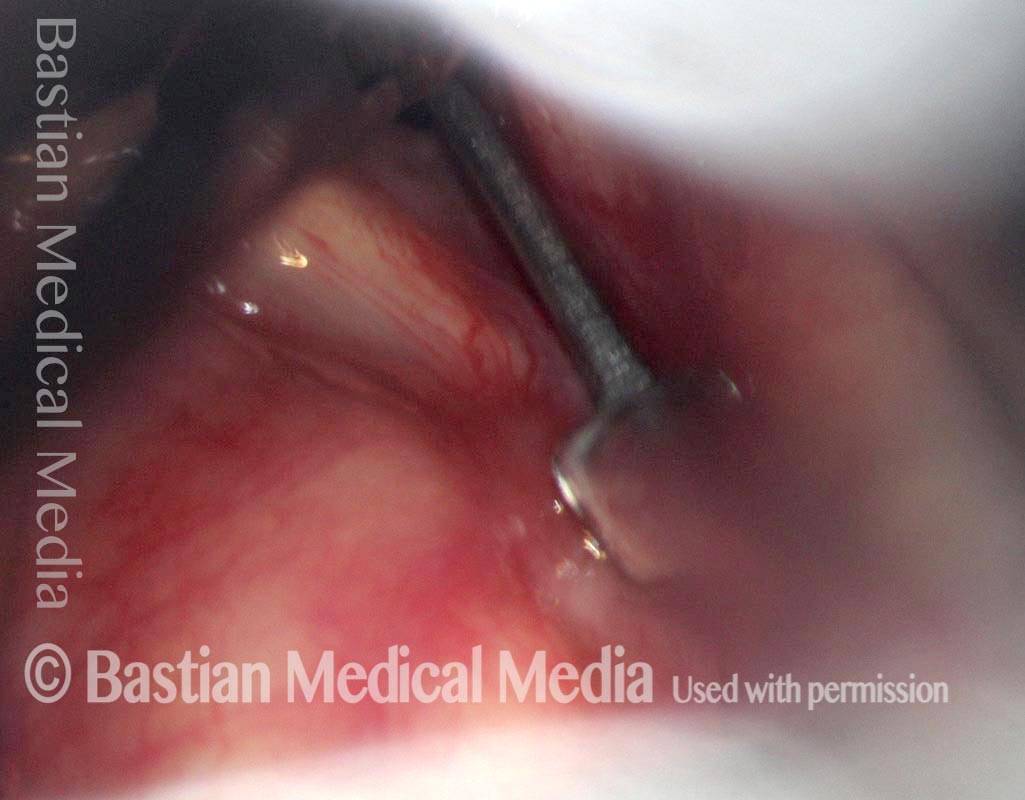

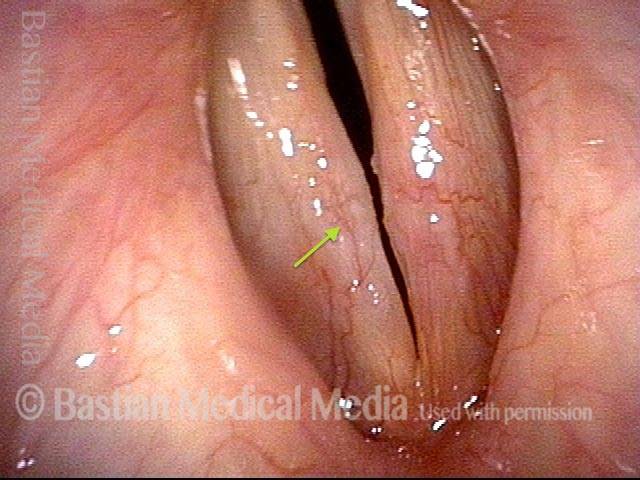

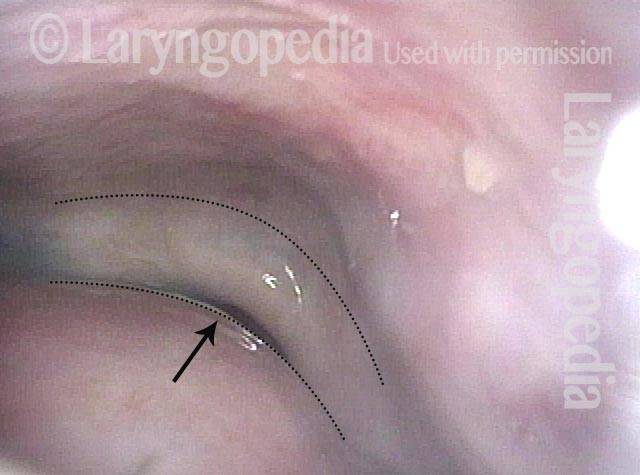

Primary “wound” (6 of 8)

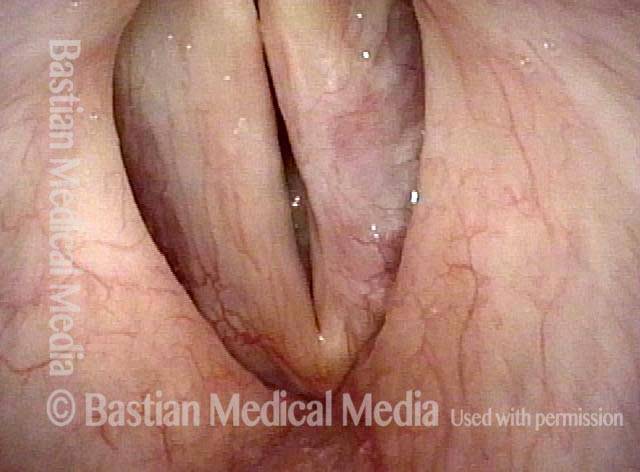

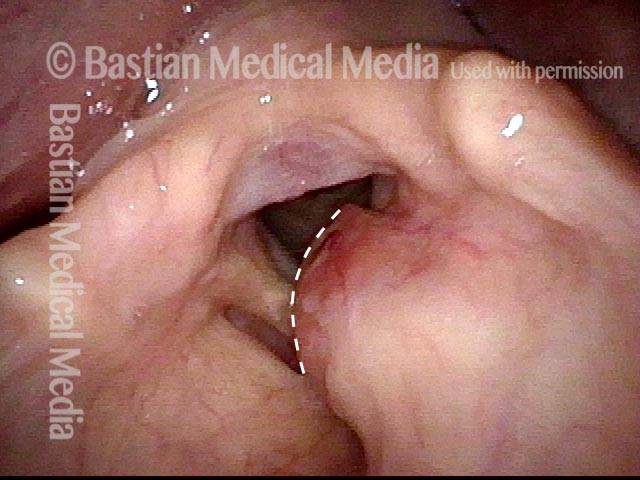

Magnified view. Primary “wound” from polyp removal is at the arrows. Edema of the opposite side is from minimal trimming on that side.

Primary “wound” (6 of 8)

Magnified view. Primary “wound” from polyp removal is at the arrows. Edema of the opposite side is from minimal trimming on that side.

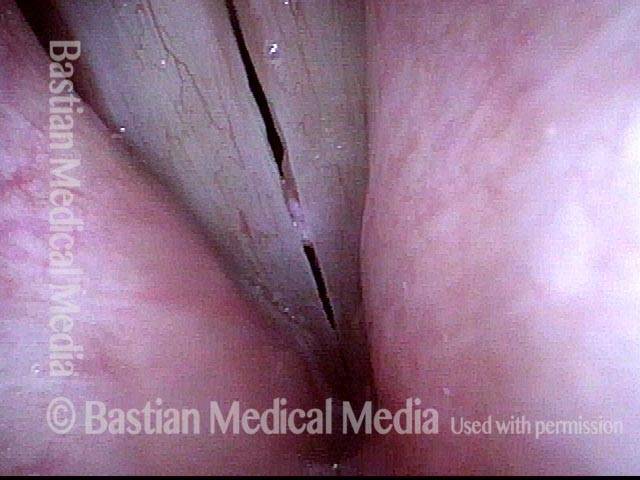

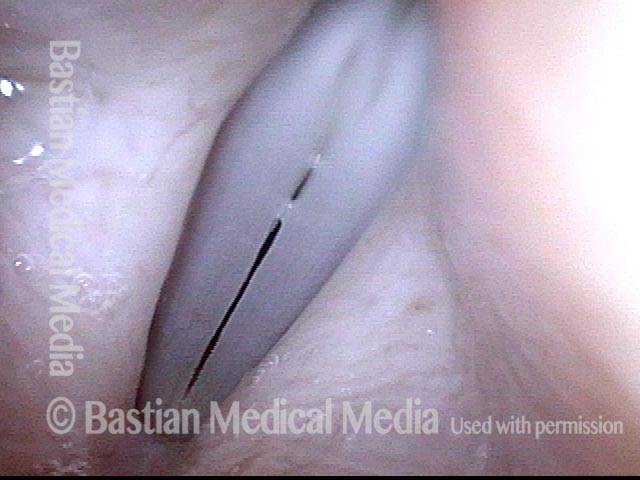

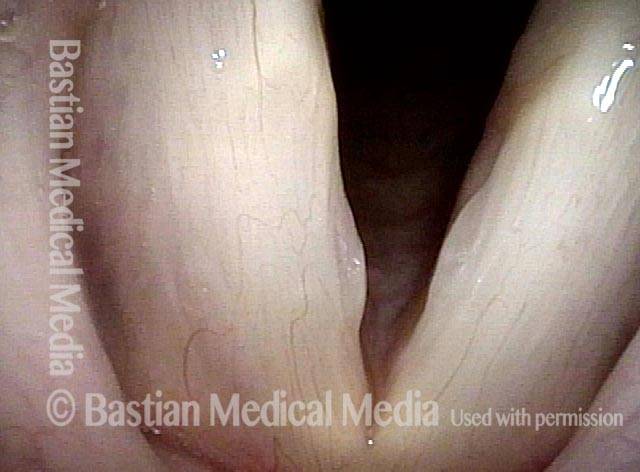

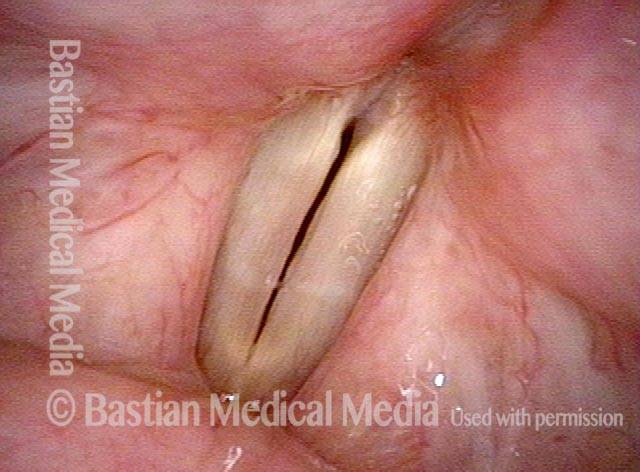

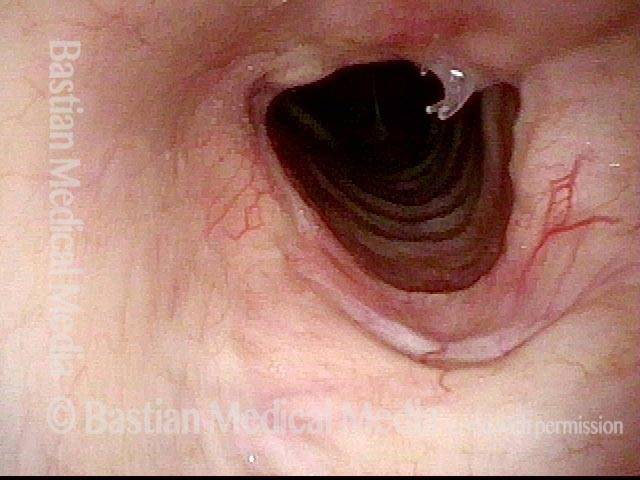

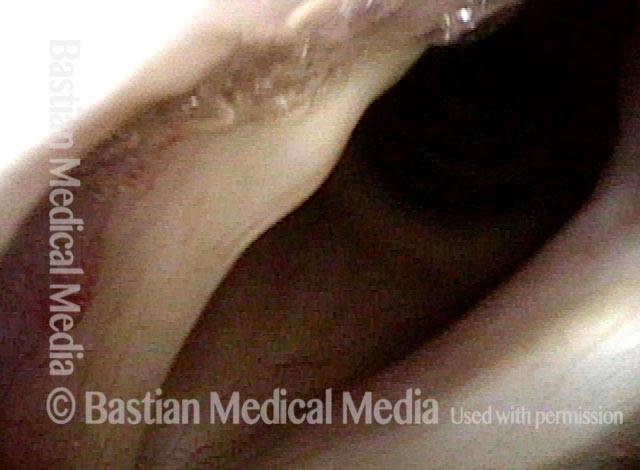

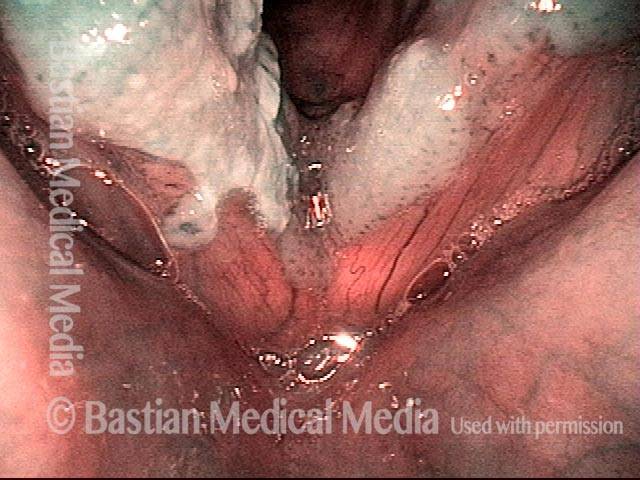

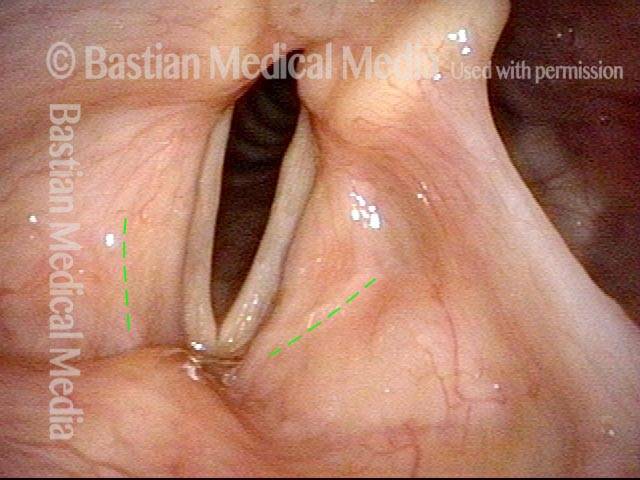

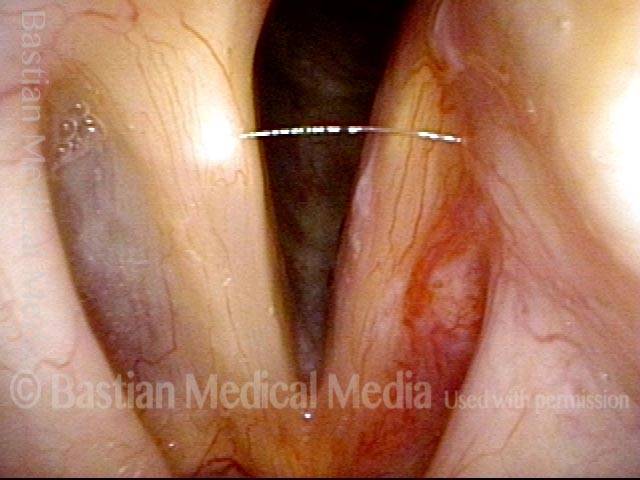

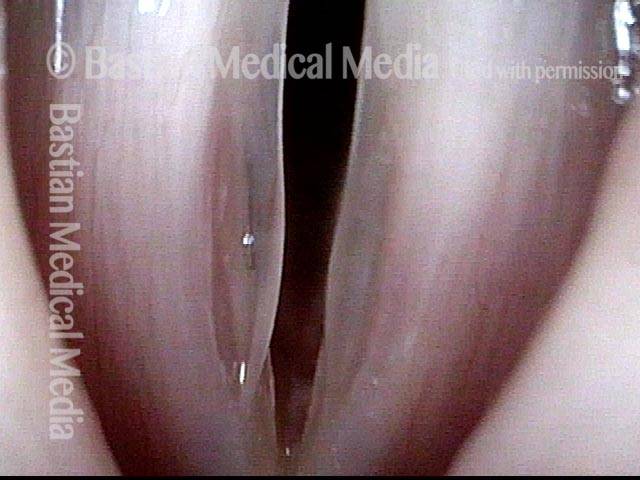

Closed phase (7 of 8)

Closed phase of vibration, strobe light, at D5 (587 Hz). Increased mucus is from endotracheal tube and surgical manipulation just hours earlier.

Closed phase (7 of 8)

Closed phase of vibration, strobe light, at D5 (587 Hz). Increased mucus is from endotracheal tube and surgical manipulation just hours earlier.

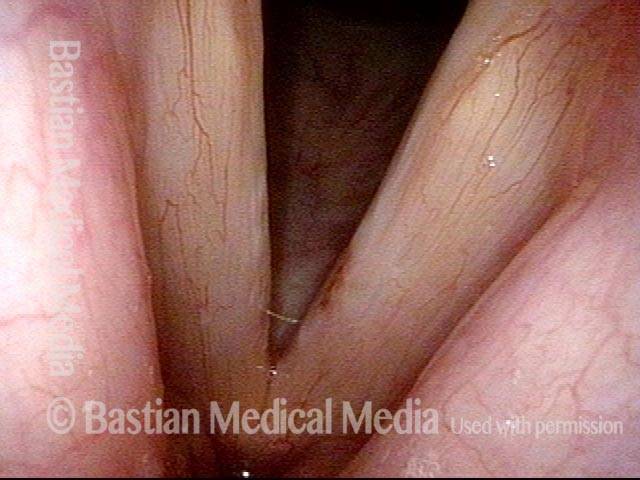

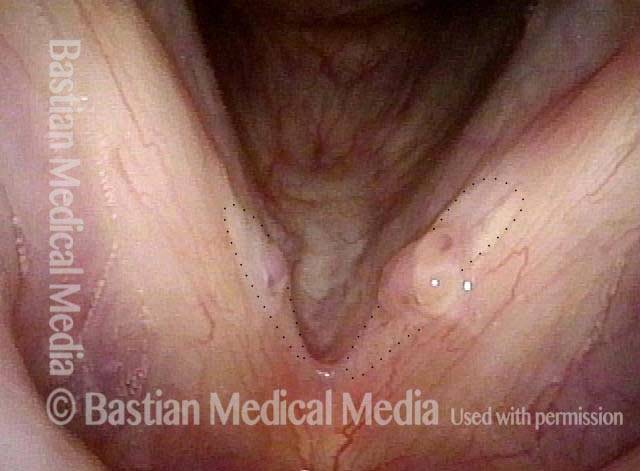

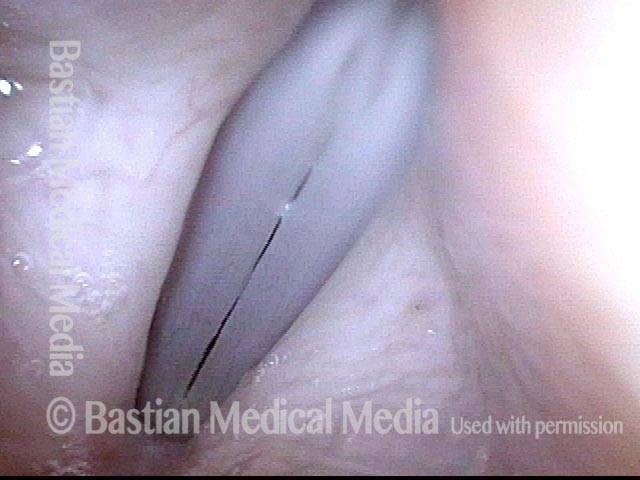

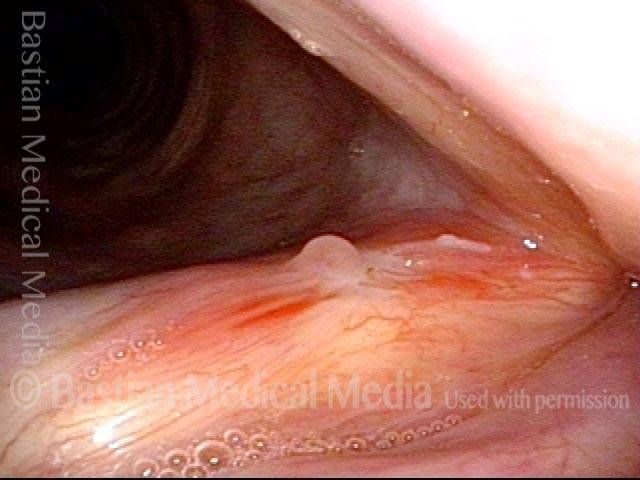

Open phase (8 of 8)

Open phase, at same pitch. Subtle irregularities will “iron out” within over time. Voice is already much better (tested briefly because the patient is within the four days of voice rest, and then will gradually increase amounts of voice use for the subsequent month).

Open phase (8 of 8)

Open phase, at same pitch. Subtle irregularities will “iron out” within over time. Voice is already much better (tested briefly because the patient is within the four days of voice rest, and then will gradually increase amounts of voice use for the subsequent month).

Hemorrhagic Polyp, before and after Surgery

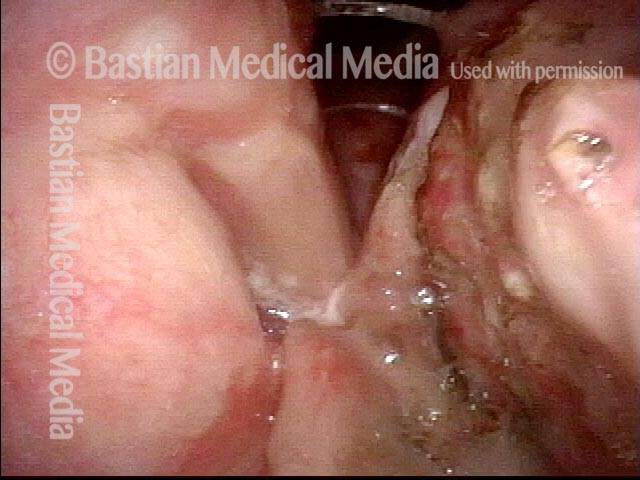

Hemorrhagic polyp (1 of 8)

Standard light, close-up view of a hemorrhagic polyp of the vocal cord.

Hemorrhagic polyp (1 of 8)

Standard light, close-up view of a hemorrhagic polyp of the vocal cord.

Hemorrhagic polyp (2 of 8)

Strobe light, open phase of vibration.

Hemorrhagic polyp (2 of 8)

Strobe light, open phase of vibration.

Hemorrhagic polyp (3 of 8)

Strobe light, closed phase of vibration.

Hemorrhagic polyp (3 of 8)

Strobe light, closed phase of vibration.

Hemorrhagic polyp: 1 week after surgery (4 of 8)

Same patient, one week after surgical removal of the polyp, standard light.

Hemorrhagic polyp: 1 week after surgery (4 of 8)

Same patient, one week after surgical removal of the polyp, standard light.

Hemorrhagic polyp: 1 week after surgery (5 of 8)

Strobe light, open phase of vibration. Compare with photo 2. Note here that the vibratory amplitude of both cords is the same, showing that the operated cord remains flexible.

Hemorrhagic polyp: 1 week after surgery (5 of 8)

Strobe light, open phase of vibration. Compare with photo 2. Note here that the vibratory amplitude of both cords is the same, showing that the operated cord remains flexible.

Hemorrhagic polyp: 1 week after surgery (6 of 8)

Strobe light, closed phase of vibration. Compare with photo 3; the vocal cords now match much better during voicing, and the voice is completely normalized.

Hemorrhagic polyp: 1 week after surgery (6 of 8)

Strobe light, closed phase of vibration. Compare with photo 3; the vocal cords now match much better during voicing, and the voice is completely normalized.

Hemorrhagic polyp: 7 months after surgery (7 of 8)

Seven months later. Strobe light, closed phase of vibration. The patient feels his voice is normal, and swelling checks don't indicate any impairment.

Hemorrhagic polyp: 7 months after surgery (7 of 8)

Seven months later. Strobe light, closed phase of vibration. The patient feels his voice is normal, and swelling checks don't indicate any impairment.

Hemorrhagic polyp: 7 months after surgery (8 of 8)

Strobe light, open phase of vibration.

Hemorrhagic polyp: 7 months after surgery (8 of 8)

Strobe light, open phase of vibration.

Vocal Polyp, Before and After Surgery

Vocal polyp (1 of 2)

Chronic polyp on the right vocal cord (left of image), with ectatic capillaries, unresponsive to voice rest and therapy.

Vocal polyp (1 of 2)

Chronic polyp on the right vocal cord (left of image), with ectatic capillaries, unresponsive to voice rest and therapy.

Vocal polyp, surgically removed (2 of 2)

Seven weeks after surgical removal and spot coagulation of ectatic capillaries. The margins of the vocal cords now match, and capillaries are normalized. Mucosal vibration is preserved to the highest reaches of the singing range. At this pre-phonatory instant, one can see that muscle memory is keeping the vocal cords slightly apart, suggesting the need for additional speech therapy.

Vocal polyp, surgically removed (2 of 2)

Seven weeks after surgical removal and spot coagulation of ectatic capillaries. The margins of the vocal cords now match, and capillaries are normalized. Mucosal vibration is preserved to the highest reaches of the singing range. At this pre-phonatory instant, one can see that muscle memory is keeping the vocal cords slightly apart, suggesting the need for additional speech therapy.

Vocal polyp (1 of 6)

Prephonatory instant, standard light. The space between the vocal cords is larger than necessary to accommodate the polyp (right of image) and low-profile elevation (left of image).

Vocal polyp (1 of 6)

Prephonatory instant, standard light. The space between the vocal cords is larger than necessary to accommodate the polyp (right of image) and low-profile elevation (left of image).

Vocal polyp (2 of 6)

Phonation with blurring, standard light.

Vocal polyp (2 of 6)

Phonation with blurring, standard light.

Vocal polyp, surgically removed (3 of 6)

Six days after surgical removal. Prephonatory instant, standard light. Compare with photo 1. The patient continues to position vocal cords in a surprisingly separated position, as though the ghosts of the swellings remain. We call this “gap memory” or “posture memory,” though it is a manifestation as well of muscular tension dysphonia.

Vocal polyp, surgically removed (3 of 6)

Six days after surgical removal. Prephonatory instant, standard light. Compare with photo 1. The patient continues to position vocal cords in a surprisingly separated position, as though the ghosts of the swellings remain. We call this “gap memory” or “posture memory,” though it is a manifestation as well of muscular tension dysphonia.

Vocal polyp, surgically removed (4 of 6)

Phonation with blurring, standard light. Compare with photo 2.

Vocal polyp, surgically removed (4 of 6)

Phonation with blurring, standard light. Compare with photo 2.

Vocal polyp, surgically removed (5 of 6)

Phonation, strobe light, open phase of vibration, at high G# (~831 Hz), just below A5. Even at this high pitch, both cords oscillate out to a full lateral excursion.

Vocal polyp, surgically removed (5 of 6)

Phonation, strobe light, open phase of vibration, at high G# (~831 Hz), just below A5. Even at this high pitch, both cords oscillate out to a full lateral excursion.

Vocal polyp, surgically removed (6 of 6)

Phonation, strobe light, closed phase of vibration, also at high G#. Since the patient is only six days postop, mild residual swelling is still present. More importantly, note that this “closed” vibration phase is not in fact fully closed, as further evidence of the patient’s “gap memory” and muscular tension dysphonia. Singing voice-qualified speech therapy and work with a singing teacher will address this.

Vocal polyp, surgically removed (6 of 6)

Phonation, strobe light, closed phase of vibration, also at high G#. Since the patient is only six days postop, mild residual swelling is still present. More importantly, note that this “closed” vibration phase is not in fact fully closed, as further evidence of the patient’s “gap memory” and muscular tension dysphonia. Singing voice-qualified speech therapy and work with a singing teacher will address this.

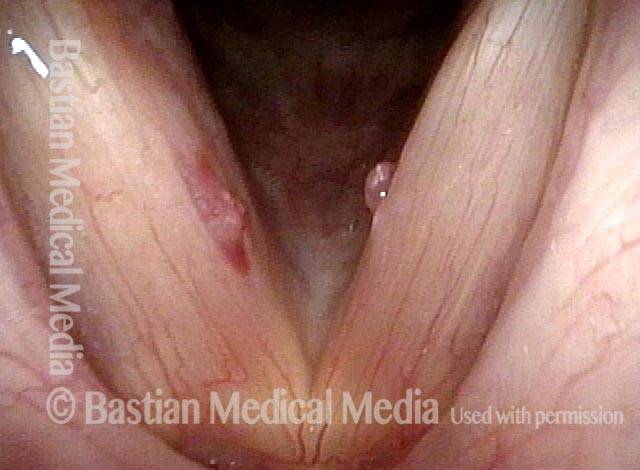

Vocal polyp (1 of 6)

An operatic baritone has a chronic left vocal cord polyp (right of image), and small contact reaction, right cord.

Vocal polyp (1 of 6)

An operatic baritone has a chronic left vocal cord polyp (right of image), and small contact reaction, right cord.

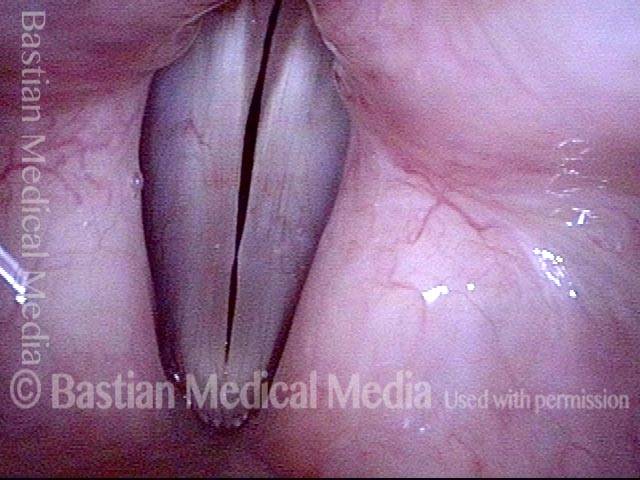

Vocal polyp (2 of 6)

Phonation, open phase of vibration, upper middle voice, showing obvious margin elevation of the left cord (right of image). Voice is hoarse.

Vocal polyp (2 of 6)

Phonation, open phase of vibration, upper middle voice, showing obvious margin elevation of the left cord (right of image). Voice is hoarse.

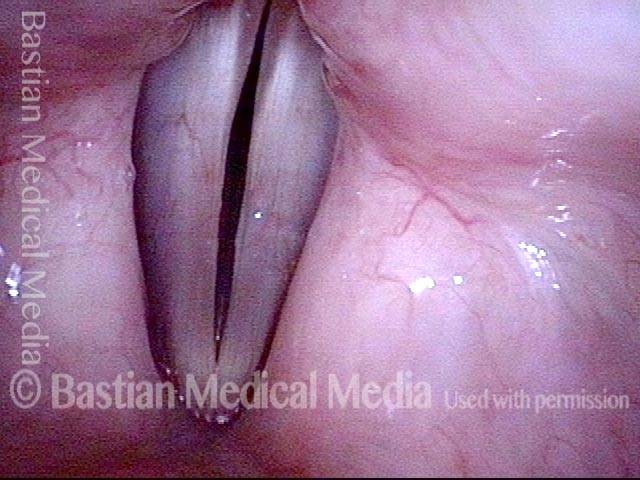

Vocal polyp (3 of 6)

Maximum closed phase of vibration, showing polyp-induced gap, causing air wasting and hoarse voice quality.

Vocal polyp (3 of 6)

Maximum closed phase of vibration, showing polyp-induced gap, causing air wasting and hoarse voice quality.

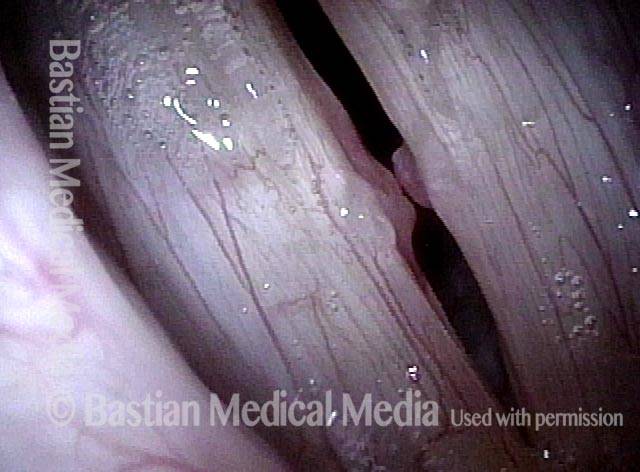

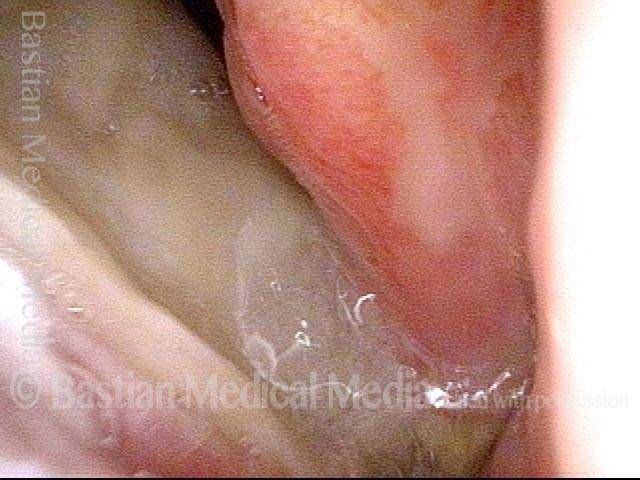

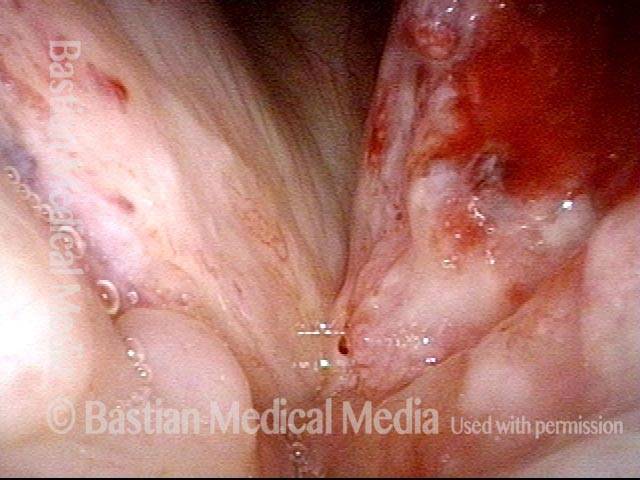

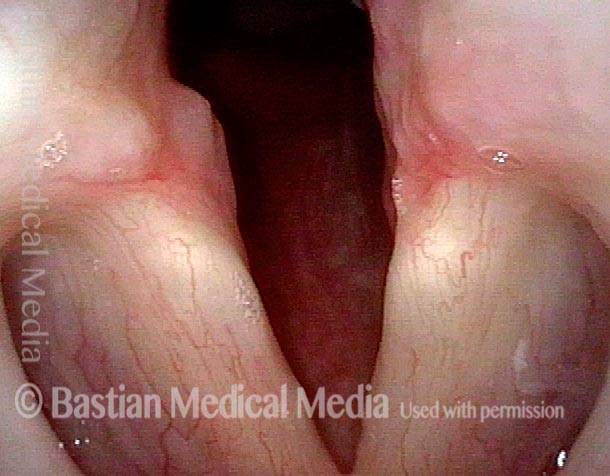

Vocal polyp, surgically removed (4 of 6)

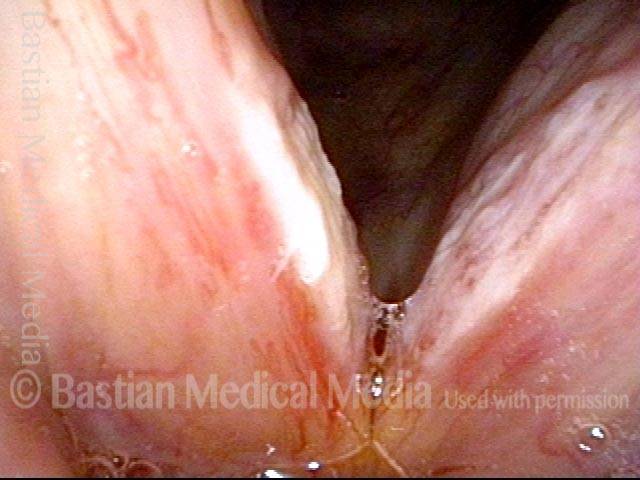

Sixth day after microlaryngoscopic removal of the polyp. Note the red, 2-millimeter “wound” where the polyp was removed.

Vocal polyp, surgically removed (4 of 6)

Sixth day after microlaryngoscopic removal of the polyp. Note the red, 2-millimeter “wound” where the polyp was removed.

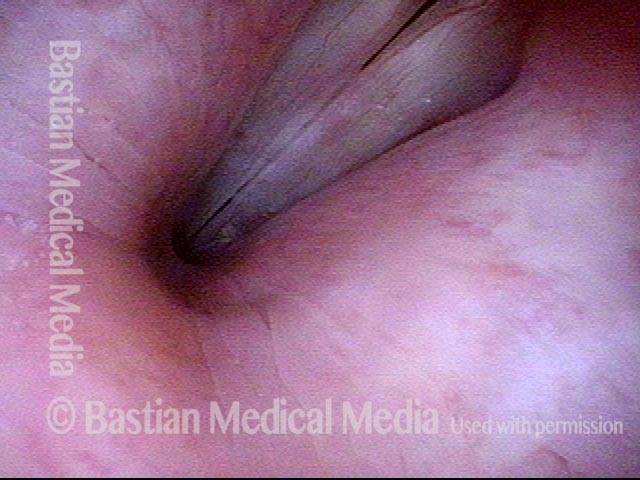

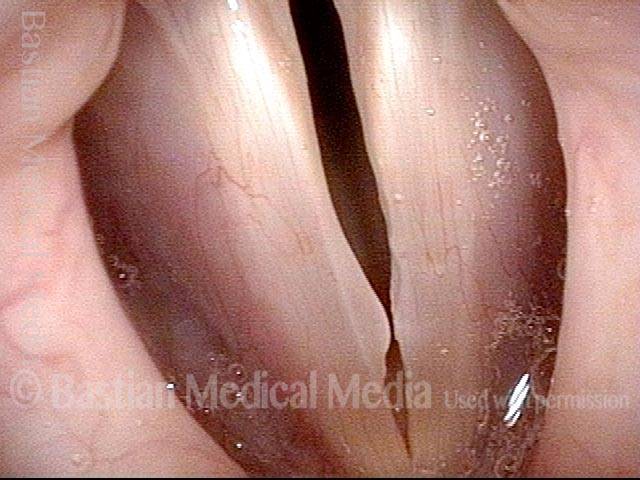

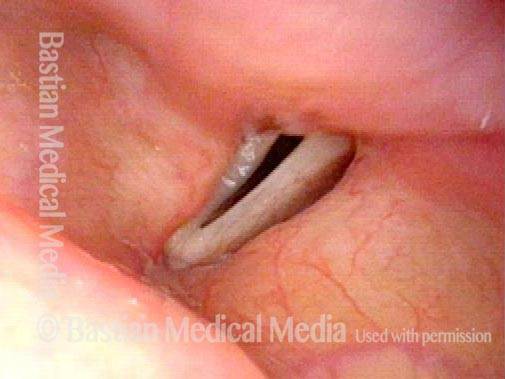

Vocal polyp, surgically removed (5 of 6)

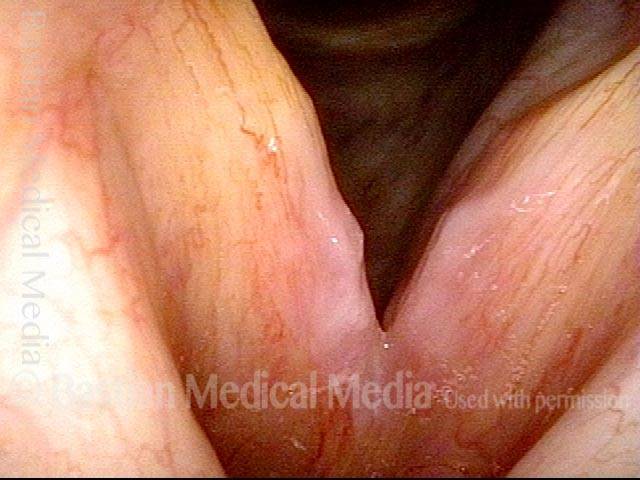

At extremely high falsetto, open phase of vibration, showing uniform width of glottic chink. Voice is normal, even at this revealing, high pitch.

Vocal polyp, surgically removed (5 of 6)

At extremely high falsetto, open phase of vibration, showing uniform width of glottic chink. Voice is normal, even at this revealing, high pitch.

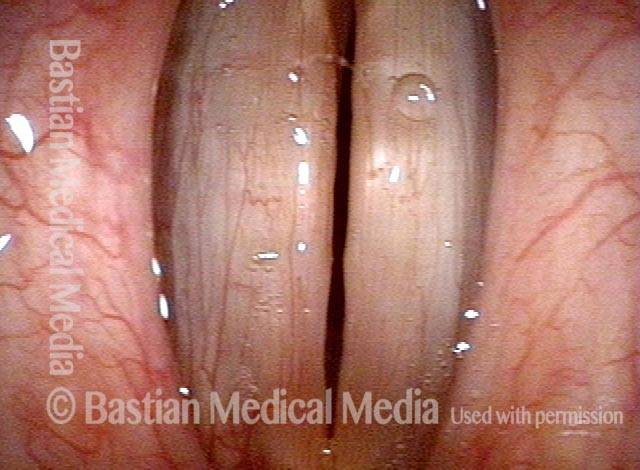

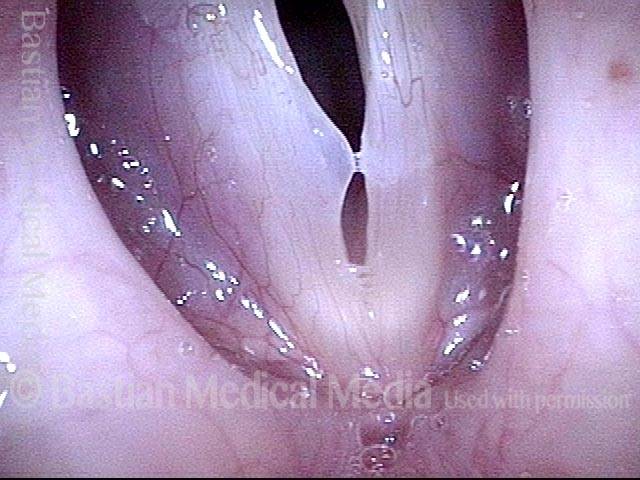

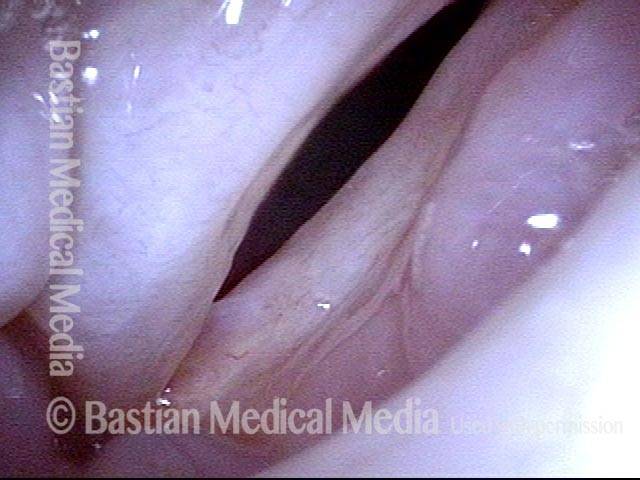

Vocal polyp, surgically removed (6 of 6)

Closed phase of vibration, high falsetto, shows equal vibratory amplitude on both sides (no stiffness) and excellent match of the cords.

Vocal polyp, surgically removed (6 of 6)

Closed phase of vibration, high falsetto, shows equal vibratory amplitude on both sides (no stiffness) and excellent match of the cords.

Pre-op and very early Post-op Mucosal Match and Flexibility in Male Singer

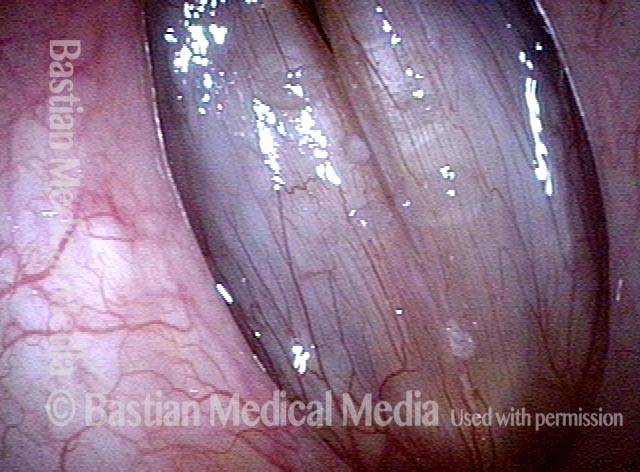

Bilateral chronic injuries (1 of 8)

Young music teacher and choral director with chronic hoarseness for more than a year. Note bilateral chronic injuries, and also recent bruise of the right cord (left of photo).

Bilateral chronic injuries (1 of 8)

Young music teacher and choral director with chronic hoarseness for more than a year. Note bilateral chronic injuries, and also recent bruise of the right cord (left of photo).

Closeup of injuries (2 of 8)

Closeup of injuries and their "refusal" to let the cords approximate, when attempting (unsuccessfully) to sing a high pitch.

Closeup of injuries (2 of 8)

Closeup of injuries and their "refusal" to let the cords approximate, when attempting (unsuccessfully) to sing a high pitch.

Post microsurgery (3 of 8)

7 days after vocal cord microsurgery, the voice can already pass for normal quality and capability. Compare with photo 1.

Post microsurgery (3 of 8)

7 days after vocal cord microsurgery, the voice can already pass for normal quality and capability. Compare with photo 1.

Prephonatory instant (4 of 8)

Prephonatory instant at high pitch, showing that the match of the cords is already markedly restored. The tiny elevation will disappear with further healing.

Prephonatory instant (4 of 8)

Prephonatory instant at high pitch, showing that the match of the cords is already markedly restored. The tiny elevation will disappear with further healing.

Closed phase, A-flat 3 (5 of 8)

Closed phase of vibration at A-flat 3 (208 Hz), seen under strobe light.

Closed phase, A-flat 3 (5 of 8)

Closed phase of vibration at A-flat 3 (208 Hz), seen under strobe light.

Open phase (6 of 8)

This open phase shows what is equally important: that both cords display equal vibratory flexibility; that is, there is no stiffness or scarring.

Open phase (6 of 8)

This open phase shows what is equally important: that both cords display equal vibratory flexibility; that is, there is no stiffness or scarring.

Dramatically improved match (7 of 8)

This man also has clear, normal falsetto voice: closed phase of vibration at A-flat 4 (415 Hz), again showing dramatically improved match.

Dramatically improved match (7 of 8)

This man also has clear, normal falsetto voice: closed phase of vibration at A-flat 4 (415 Hz), again showing dramatically improved match.

Equal mucosal flexibility (8 of 8)

Again more important is evidence of equal mucosal flexibility between the two sides, as seen in this open phase of vibration, at the same pitch.

Equal mucosal flexibility (8 of 8)

Again more important is evidence of equal mucosal flexibility between the two sides, as seen in this open phase of vibration, at the same pitch.

For more info: Vocal polyps

Vocal Nodules:

Fibrosis as a Base to Nodules, Before and After Surgery

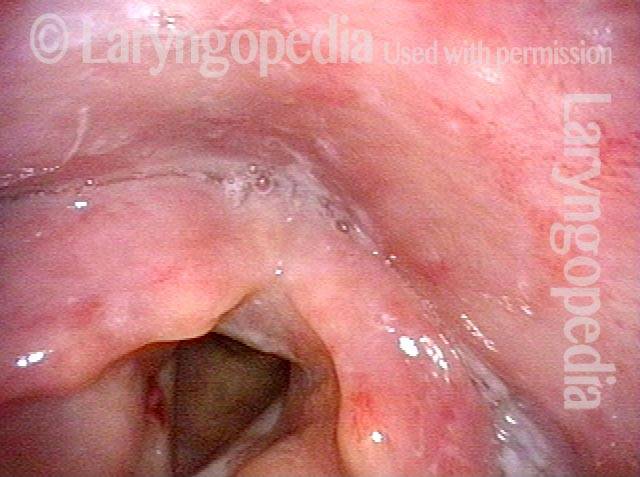

Bilateral polypoid nodules (1 of 8)

Fibrosis as a Base to Nodules, Before and After Surgery

Bilateral polypoid nodules (1 of 8)

Fibrosis as a Base to Nodules, Before and After Surgery

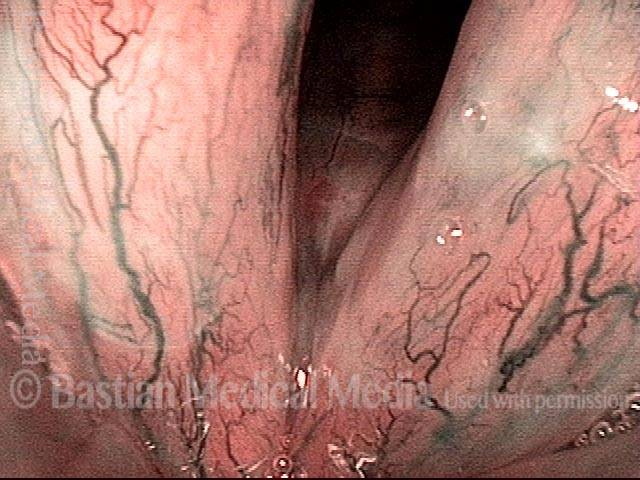

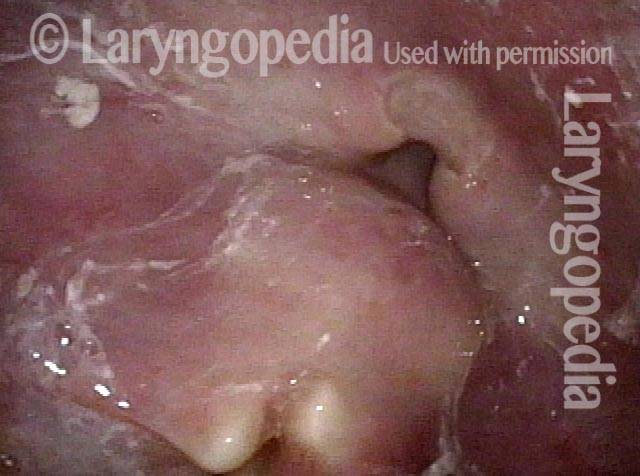

Narrow-band lighting (2 of 8)

At greater magnification, and also under narrow-band light. The area of fibrosis is more clearly seen, now without the dotted lines.

Narrow-band lighting (2 of 8)

At greater magnification, and also under narrow-band light. The area of fibrosis is more clearly seen, now without the dotted lines.

Closed phase (3 of 8)

Closed phase of vibration at ~A4 (440 Hz), as seen under strobe light.

Closed phase (3 of 8)

Closed phase of vibration at ~A4 (440 Hz), as seen under strobe light.

Open phase (4 of 8)

Open phase of vibration also at ~ A4.

Open phase (4 of 8)

Open phase of vibration also at ~ A4.

Two weeks after surgery (5 of 8)

Less than two weeks after surgical removal of the polyps. The faint white zone of margin fibrosis is again seen. Compare with photo 1.

Two weeks after surgery (5 of 8)

Less than two weeks after surgical removal of the polyps. The faint white zone of margin fibrosis is again seen. Compare with photo 1.

Phonation (6 of 8)

Phonation under standard light shows that vocal cord margins now match, and both margins blur; suggesting vibratory flexibility.

Phonation (6 of 8)

Phonation under standard light shows that vocal cord margins now match, and both margins blur; suggesting vibratory flexibility.

Margin fibrosis (7 of 8)

Closed phase of vibration, at ~ A4 (440 Hz), as seen under strobe light. Margin fibrosis seen best here, indicated by the black dotted line. Compare with photo 3.

Margin fibrosis (7 of 8)

Closed phase of vibration, at ~ A4 (440 Hz), as seen under strobe light. Margin fibrosis seen best here, indicated by the black dotted line. Compare with photo 3.

Open phase (8 of 8)

Open phase of vibration. The same pitch (A4) reveals excellent vibratory flexibility and equal amplitude (lateral excursion) of vibration. Compare with photo 4.

Open phase (8 of 8)

Open phase of vibration. The same pitch (A4) reveals excellent vibratory flexibility and equal amplitude (lateral excursion) of vibration. Compare with photo 4.

Vocal Nodules, Before and After Surgery

Vocal nodules (1 of 6)

Strobe light, phonation, open phase of vibration, at the pitch D5 (~587 Hz). There are vocal nodules on both vocal cords, of very long duration, even after voice rest and speech therapy. Compare with photos 3 and 5.

Vocal nodules (1 of 6)

Strobe light, phonation, open phase of vibration, at the pitch D5 (~587 Hz). There are vocal nodules on both vocal cords, of very long duration, even after voice rest and speech therapy. Compare with photos 3 and 5.

Breathy voice (2 of 6)

Same as photo 1, but during the closed phase of vibration. The nodules keep the vocal cords from coming together completely (as seen here), making the patient’s voice breathy. Compare with photos 4 and 6.

Breathy voice (2 of 6)

Same as photo 1, but during the closed phase of vibration. The nodules keep the vocal cords from coming together completely (as seen here), making the patient’s voice breathy. Compare with photos 4 and 6.

1 week after surgery (3 of 6)

One week after surgical removal of the vocal nodules. Strobe light, phonation, open phase of vibration, at the pitch B5 (~988 Hz). (The small “blob” seen at the midpoint of the cords is just incidental mucus.)

1 week after surgery (3 of 6)

One week after surgical removal of the vocal nodules. Strobe light, phonation, open phase of vibration, at the pitch B5 (~988 Hz). (The small “blob” seen at the midpoint of the cords is just incidental mucus.)

Closed phase (4 of 6)

Same as photo 3, but during the closed phase of vibration.

Closed phase (4 of 6)

Same as photo 3, but during the closed phase of vibration.

7 weeks after surgery (5 of 6)

Seven weeks after surgical removal of the nodules. Strobe light, phonation, open phase of vibration, at the pitch C#6 (~1109 Hz). (Incidental mucus is obscuring the posterior end of the vocal cords.)

7 weeks after surgery (5 of 6)

Seven weeks after surgical removal of the nodules. Strobe light, phonation, open phase of vibration, at the pitch C#6 (~1109 Hz). (Incidental mucus is obscuring the posterior end of the vocal cords.)

7 weeks after surgery (6 of 6)

Same as photo 5, but during the closed phase of vibration. Voice is no longer breathy, and the upper range has been restored.

7 weeks after surgery (6 of 6)

Same as photo 5, but during the closed phase of vibration. Voice is no longer breathy, and the upper range has been restored.

Vocal nodules (1 of 10)

Vocal nodules under standard light. Note asymmetry in size.

Vocal nodules (1 of 10)

Vocal nodules under standard light. Note asymmetry in size.

Prephonatory instant (2 of 10)

Prephonatory instant, standard light.

Prephonatory instant (2 of 10)

Prephonatory instant, standard light.

Translucency (3 of 10)

Closed phase of vibration, with notable translucency of the right vocal cord (left of image), which is often a predictor of chronicity and only partial response to speech (voice) therapy.

Translucency (3 of 10)

Closed phase of vibration, with notable translucency of the right vocal cord (left of image), which is often a predictor of chronicity and only partial response to speech (voice) therapy.

Open phase (4 of 10)

Open phase of vibration, strobe light.

Open phase (4 of 10)

Open phase of vibration, strobe light.

1 week after surgery (5 of 10)

A week after vocal cord microsurgery, standard light.

1 week after surgery (5 of 10)

A week after vocal cord microsurgery, standard light.

1 week after surgery (6 of 10)

Open phase of vibration, strobe light.

1 week after surgery (6 of 10)

Open phase of vibration, strobe light.

1 week after surgery (7 of 10)

Closed phase of vibration, strobe light, showing tiny margin elevations, bilaterally.

1 week after surgery (7 of 10)

Closed phase of vibration, strobe light, showing tiny margin elevations, bilaterally.

Vocal nodules: 10 weeks after surgery (8 of 10)

Prephonatory instant shows recurrent swelling due to persistent vocal overuse, despite careful preoperative preparation for surgery by a voice-qualified speech pathologist. Patients must know “we are only operating on your vocal cords, not your personality, occupation, friend group, social life, etc.”

Vocal nodules: 10 weeks after surgery (8 of 10)

Prephonatory instant shows recurrent swelling due to persistent vocal overuse, despite careful preoperative preparation for surgery by a voice-qualified speech pathologist. Patients must know “we are only operating on your vocal cords, not your personality, occupation, friend group, social life, etc.”

10 weeks after surgery (9 of 10)

Open phase of vibration, strobe light.

10 weeks after surgery (9 of 10)

Open phase of vibration, strobe light.

10 weeks after surgery (10 of 10)

Closed phase of vibration, strobe light. The “original equipment” capabilities of the voice early after successful vocal cord microsurgery (above) have been diminished, but capabilities remain markedly better than they were with the original lesions.

10 weeks after surgery (10 of 10)

Closed phase of vibration, strobe light. The “original equipment” capabilities of the voice early after successful vocal cord microsurgery (above) have been diminished, but capabilities remain markedly better than they were with the original lesions.

Vocal nodules (1 of 4)

Vocal nodules, moderately large, seen with cords in abducted (breathing) position.

Vocal nodules (1 of 4)

Vocal nodules, moderately large, seen with cords in abducted (breathing) position.

Phonation (2 of 4)

Phonation, showing early contact of the nodules, and large gaps anterior and posterior to the nodules.

Phonation (2 of 4)

Phonation, showing early contact of the nodules, and large gaps anterior and posterior to the nodules.

After surgery (3 of 4)

Phonatory position, after surgical removal. Note the straightened vocal cord margins.

After surgery (3 of 4)

Phonatory position, after surgical removal. Note the straightened vocal cord margins.

After surgery (4 of 4)

Breathing position, also post-surgery.

After surgery (4 of 4)

Breathing position, also post-surgery.

Pre-and 1 Week Post-removal Vocal Nodules

Vocal nodules (1 of 8)

Semi-professional high soprano with grossly impaired upper voice due to polypoid (fusiform) vocal nodule.

Vocal nodules (1 of 8)

Semi-professional high soprano with grossly impaired upper voice due to polypoid (fusiform) vocal nodule.

Muscular tension dysphonia (2 of 8)

Phonatory view shows a degree of muscular tension dysphonia (separated vocal processes), too.

Muscular tension dysphonia (2 of 8)

Phonatory view shows a degree of muscular tension dysphonia (separated vocal processes), too.

Open phase (3 of 8)

Nearly open phase under strobe light at B4 (494 Hz).

Open phase (3 of 8)

Nearly open phase under strobe light at B4 (494 Hz).

Closed phase (4 of 8)

Closed phase of vibration, aslo at B4.

Closed phase (4 of 8)

Closed phase of vibration, aslo at B4.

Post-op, one week (5 of 8)

A week after surgical removal of the nodules, at the prephonatory instant, D5, showing margin irregularity.

Post-op, one week (5 of 8)

A week after surgical removal of the nodules, at the prephonatory instant, D5, showing margin irregularity.

Phonation (6 of 8)

Phonation, with vibratory blur under standard light.

Phonation (6 of 8)

Phonation, with vibratory blur under standard light.

Open phase (7 of 8)

Open phase of vibration (strobe light), at D5 (587 Hz). Irregular margins will iron out across time.

Open phase (7 of 8)

Open phase of vibration (strobe light), at D5 (587 Hz). Irregular margins will iron out across time.

Closed phase (8 of 8)

At closed phase of vibration, also at D5. Note excellent match, bilaterally equal vibratory excursions, and partial correction of the MTD posterior commissure gap.

Closed phase (8 of 8)

At closed phase of vibration, also at D5. Note excellent match, bilaterally equal vibratory excursions, and partial correction of the MTD posterior commissure gap.

Vocal Nodule Postop Irregularity yet Match and Flexibility

Large vocal nodules (1 of 8)

Bilateral large vocal nodules in band singer that does close harmony musical styles.

Large vocal nodules (1 of 8)

Bilateral large vocal nodules in band singer that does close harmony musical styles.

Narrow band light (2 of 8)

Now under narrow band light to accentuate the vascular pattern.

Narrow band light (2 of 8)

Now under narrow band light to accentuate the vascular pattern.

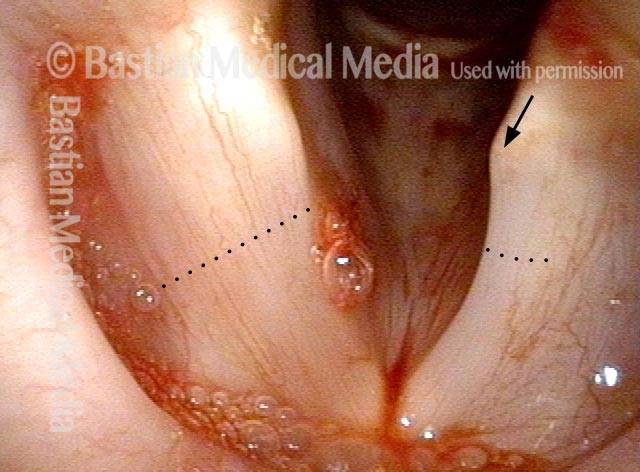

One week after surgery (5 of 8)

A week after surgery, the “wounds” measure about 3mm long (at arrows).

One week after surgery (5 of 8)

A week after surgery, the “wounds” measure about 3mm long (at arrows).

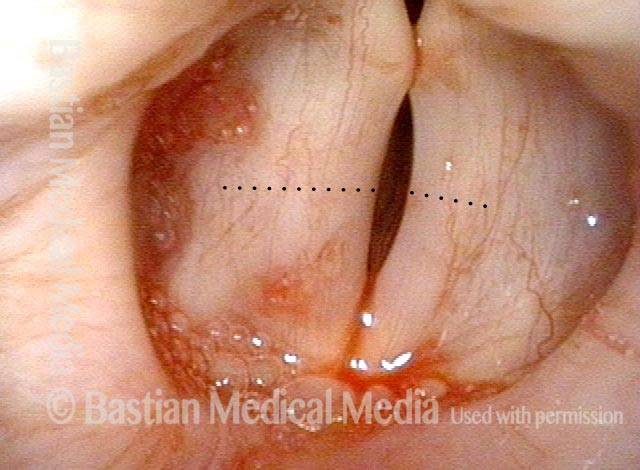

Prephonatory instant (6 of 8)

Prephonatory instant, standard light, at C#5 (554 Hz).

Prephonatory instant (6 of 8)

Prephonatory instant, standard light, at C#5 (554 Hz).

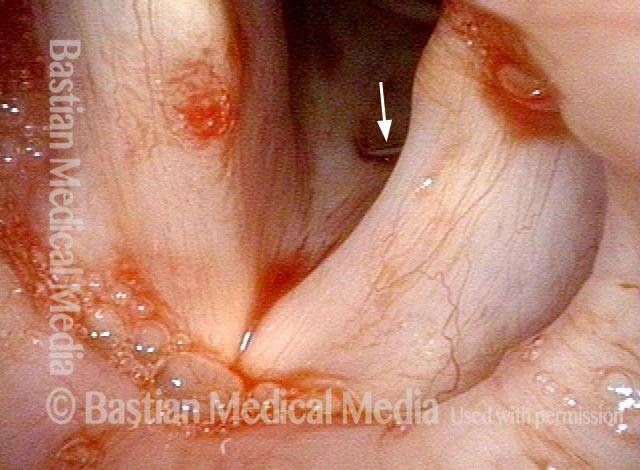

Open phase (7 of 8)

Open phase of vibration at E5 (659 Hz). Voice is markedly improved.

Open phase (7 of 8)

Open phase of vibration at E5 (659 Hz). Voice is markedly improved.

For more info: Vocal nodules

Cancer:

Vocal Cord Cancer, before and after Surgery

Vocal cord cancer (1 of 4)

Squamous cell carcinoma, right vocal cord (left of image), standard light.

Vocal cord cancer (1 of 4)

Squamous cell carcinoma, right vocal cord (left of image), standard light.

Vocal cord cancer, 1 week after surgery (2 of 4)

One week after laser excision. See irregular granulation especially at lower margin of excision.

Vocal cord cancer, 1 week after surgery (2 of 4)

One week after laser excision. See irregular granulation especially at lower margin of excision.

Vocal cord cancer, 1 month after surgery (3 of 4)

Approximately one month after excision, healing progressing.

Vocal cord cancer, 1 month after surgery (3 of 4)

Approximately one month after excision, healing progressing.

Vocal cord cancer, after complete healing (4 of 4)

After complete healing, patient has a voice that passes for normal. Under strobe light, right cord oscillates well except at very high vocal pitch. Note, however, the mild pseudo-bowing of the right cord due to tissue loss, and that there is a mucosal wave on the left, but not on the right.

Vocal cord cancer, after complete healing (4 of 4)

After complete healing, patient has a voice that passes for normal. Under strobe light, right cord oscillates well except at very high vocal pitch. Note, however, the mild pseudo-bowing of the right cord due to tissue loss, and that there is a mucosal wave on the left, but not on the right.

Vocal cord cancer (1 of 8)

Patient from elsewhere, first seen 9 months after radiotherapy, with obvious persistent right vocal cord cancer.

Vocal cord cancer (1 of 8)

Patient from elsewhere, first seen 9 months after radiotherapy, with obvious persistent right vocal cord cancer.

Vocal cord cancer (2 of 8)

Closer view, during phonation, showing deep ulceration and rolled upper and lower border of cancer.

Vocal cord cancer (2 of 8)

Closer view, during phonation, showing deep ulceration and rolled upper and lower border of cancer.

Vocal cord cancer, 1 week after surgery (3 of 8)

One week after aggressive cordectomy, right, including down to inner perichondrium of thyroid cartilage.

Vocal cord cancer, 1 week after surgery (3 of 8)

One week after aggressive cordectomy, right, including down to inner perichondrium of thyroid cartilage.

Vocal cord cancer, 1 week after surgery (4 of 8)

Phonation, showing that the left vocal cord now has no “partner” against which to vibrate, and this explains the marked breathiness.

Vocal cord cancer, 1 week after surgery (4 of 8)

Phonation, showing that the left vocal cord now has no “partner” against which to vibrate, and this explains the marked breathiness.

Vocal cord cancer, 7 weeks after surgery (5 of 8)

Nearly complete healing after complete cordectomy right vocal cord. Only residual granulation.

Vocal cord cancer, 7 weeks after surgery (5 of 8)

Nearly complete healing after complete cordectomy right vocal cord. Only residual granulation.

Vocal cord cancer, 7 weeks after surgery (6 of 8)

Closer view of defect. Thin mucosa covers inner surface of thyroid cartilage, and residual exposed cartilage, not yet healed over with mucosa, at arrow.

Vocal cord cancer, 7 weeks after surgery (6 of 8)

Closer view of defect. Thin mucosa covers inner surface of thyroid cartilage, and residual exposed cartilage, not yet healed over with mucosa, at arrow.

Vocal cord cancer, 7 weeks after surgery (7 of 8)

At maximum phonatory adduction. Note that the left vocal process is turned medially (arrow), signifying maximum adductory “effort” of that side. There is no right vocal cord, and hence there is no possibility of glottic voice.

Vocal cord cancer, 7 weeks after surgery (7 of 8)

At maximum phonatory adduction. Note that the left vocal process is turned medially (arrow), signifying maximum adductory “effort” of that side. There is no right vocal cord, and hence there is no possibility of glottic voice.

Vocal cord cancer, 7 weeks after surgery (8 of 8)

Vibration of the arytenoid apices (arrows) against the petiole of the epiglottis (line), providing a rough, voice serviceable for quiet conversation, but highly limited in noisy surroundings.

Vocal cord cancer, 7 weeks after surgery (8 of 8)

Vibration of the arytenoid apices (arrows) against the petiole of the epiglottis (line), providing a rough, voice serviceable for quiet conversation, but highly limited in noisy surroundings.

Scarring after Cancer Treatment but with very Good Voice

Post laser excision (1 of 4)

Ten years after laser excision of a left vocal cord (right of photo) cancer, viewed from a distance. Voice has been extremely serviceable, if slightly husky.

Post laser excision (1 of 4)

Ten years after laser excision of a left vocal cord (right of photo) cancer, viewed from a distance. Voice has been extremely serviceable, if slightly husky.

Prephonatory instant (2 of 4)

Closer visualization at the prephonatory instant. Now the pseudobowing of the left cord (from tissue loss is easily seen.

Prephonatory instant (2 of 4)

Closer visualization at the prephonatory instant. Now the pseudobowing of the left cord (from tissue loss is easily seen.

Phonation (3 of 4)

Making voice, the faint blurring of the right cord margin (left of photo), but non-vibrating left cord (right of photo) can be more easily appreciated.

Phonation (3 of 4)

Making voice, the faint blurring of the right cord margin (left of photo), but non-vibrating left cord (right of photo) can be more easily appreciated.

Close-up view (4 of 4)

At very close range, medial-to-lateral capillary reorientation—typical of superficial cordectomy after healing.

Close-up view (4 of 4)

At very close range, medial-to-lateral capillary reorientation—typical of superficial cordectomy after healing.

Vocal Cord Cancer, before, during, and after Radiation

Vocal cord cancer (1 of 8)

Superficial cancer involving both vocal cords. This is stage 1 disease (T1B). The greatest bulk is on the right posterior cord (left of image), but the majority of both cords is involved with at least superficial disease. A faint dotted rectangle indicates the zoomed-in area seen in photo 2.

Vocal cord cancer (1 of 8)

Superficial cancer involving both vocal cords. This is stage 1 disease (T1B). The greatest bulk is on the right posterior cord (left of image), but the majority of both cords is involved with at least superficial disease. A faint dotted rectangle indicates the zoomed-in area seen in photo 2.

Vocal cord cancer (2 of 8)

Close-up view of only the anterior half of the cords. Notice the irregular surface, and areas of leukoplakia within this squamous cell carcinoma.

Vocal cord cancer (2 of 8)

Close-up view of only the anterior half of the cords. Notice the irregular surface, and areas of leukoplakia within this squamous cell carcinoma.

Vocal cord cancer, during radiation (3 of 8)

Just over midway through radiation treatment. One can see that the tumor is melting away.

Vocal cord cancer, during radiation (3 of 8)

Just over midway through radiation treatment. One can see that the tumor is melting away.

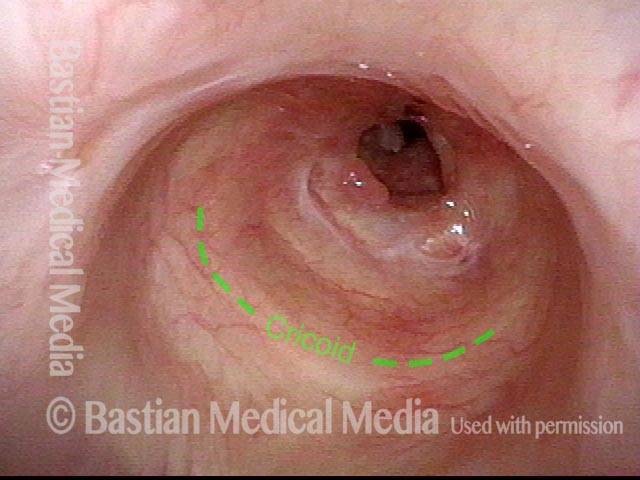

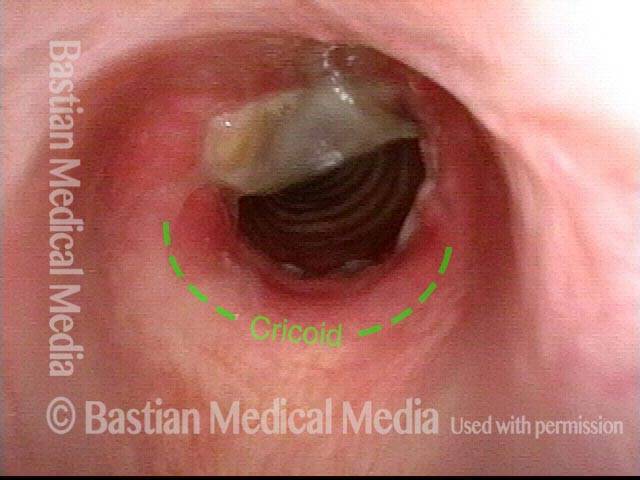

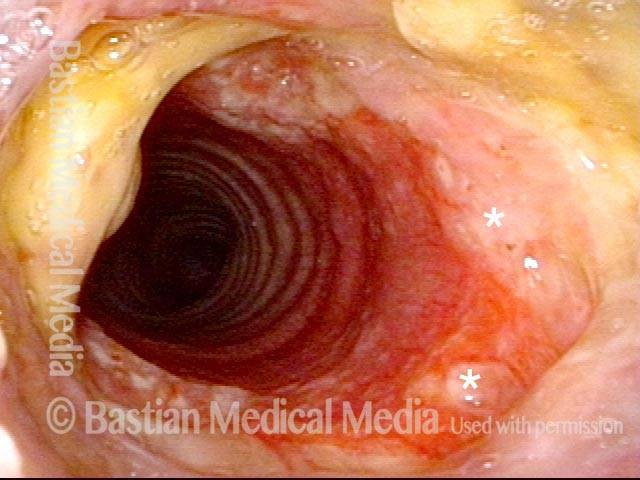

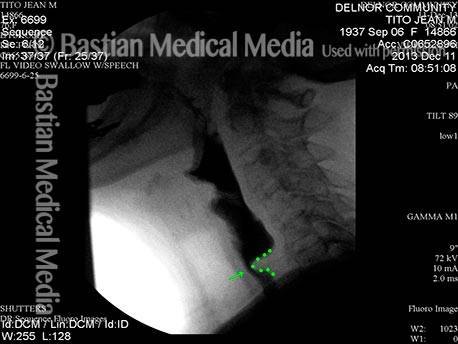

Vocal cord cancer, during radiation (4 of 8)

Postcricoid / hypopharyngeal mucositis. In this view, the patient is performing a so-called trumpet maneuver to splay open the lower throat. The radiation delivered to the vocal cords (which inhabit the airway but are hidden here due to the momentary constriction of the laryngeal vestibule, at arrows) also causes superficial ulceration of the swallowing passage (upper half of the photo), directly behind the vocal cords. On occasion, if tissue reaction and mucositis are much more severe than seen here, a stricture can form, requiring dilation.

Vocal cord cancer, during radiation (4 of 8)

Postcricoid / hypopharyngeal mucositis. In this view, the patient is performing a so-called trumpet maneuver to splay open the lower throat. The radiation delivered to the vocal cords (which inhabit the airway but are hidden here due to the momentary constriction of the laryngeal vestibule, at arrows) also causes superficial ulceration of the swallowing passage (upper half of the photo), directly behind the vocal cords. On occasion, if tissue reaction and mucositis are much more severe than seen here, a stricture can form, requiring dilation.

Vocal cord cancer, 2 months after radiation (5 of 8)

Two months after radiation is complete, showing that the tumor is gone, and the mucositis has resolved. There is a small anterior commissure web (at arrow) just below the free margin of the cords. The patient’s voice can nevertheless pass for normal.

Vocal cord cancer, 2 months after radiation (5 of 8)

Two months after radiation is complete, showing that the tumor is gone, and the mucositis has resolved. There is a small anterior commissure web (at arrow) just below the free margin of the cords. The patient’s voice can nevertheless pass for normal.

Vocal cord cancer, 4 months after radiation (6 of 8)

Now four months after the end of radiation. Close-up view of the postcricoid / hypopharynx regions (compare with photo 4 in this series). Mucositis here is resolved as well, and there is no stricture.

Vocal cord cancer, 4 months after radiation (6 of 8)

Now four months after the end of radiation. Close-up view of the postcricoid / hypopharynx regions (compare with photo 4 in this series). Mucositis here is resolved as well, and there is no stricture.

Vocal cord cancer, 6 months after radiation (7 of 8)

Now six months after the end of radiation. Strobe illumination, open phase of vibration. Note that the contours of the vocal cords are not perfectly normal, even though voice is very good.

Vocal cord cancer, 6 months after radiation (7 of 8)

Now six months after the end of radiation. Strobe illumination, open phase of vibration. Note that the contours of the vocal cords are not perfectly normal, even though voice is very good.

Vocal cord cancer, 6 months after radiation (8 of 8)

Strobe illumination, nearly closed phase of vibration. Oscillatory flexibility is preserved, but the vocal cord margins are not perfectly straight.

Vocal cord cancer, 6 months after radiation (8 of 8)

Strobe illumination, nearly closed phase of vibration. Oscillatory flexibility is preserved, but the vocal cord margins are not perfectly straight.

Vocal Cord Cancer, before and after Radiotherapy

Vocal cord cancer (1 of 7)

A 66-year-old man who complains of hoarseness. He smoked a pack a day for 50 years but quit five years ago. Note here the fullness and irregular contour especially of the left vocal cord ( right of photo). A biopsy confirmed this was cancer.

Vocal cord cancer (1 of 7)

A 66-year-old man who complains of hoarseness. He smoked a pack a day for 50 years but quit five years ago. Note here the fullness and irregular contour especially of the left vocal cord ( right of photo). A biopsy confirmed this was cancer.

Vocal cord cancer (2 of 7)

At closer range, scattered leukoplakia and stippled vascular markings (suggestive of HPV effect, but HPV tested negative).

Vocal cord cancer (2 of 7)

At closer range, scattered leukoplakia and stippled vascular markings (suggestive of HPV effect, but HPV tested negative).

Vocal cord cancer, 3 weeks after radiotherapy (4 of 7)

Same patient, three weeks after the end of full-course radiotherapy. Distant view shows radiation-induced mucositis on the false and true cords, seen as areas of white, superficial ulceration. General redness is also a radiation effect.

Vocal cord cancer, 3 weeks after radiotherapy (4 of 7)

Same patient, three weeks after the end of full-course radiotherapy. Distant view shows radiation-induced mucositis on the false and true cords, seen as areas of white, superficial ulceration. General redness is also a radiation effect.

Vocal cord cancer, 3 weeks after radiotherapy (5 of 7)

Closer view, showing that the main tumor of the left vocal cord (again, right of photo) has melted away. Note that the mucositis is generalized, and not necessarily focal to the area of tumor sloughing.

Vocal cord cancer, 3 weeks after radiotherapy (5 of 7)

Closer view, showing that the main tumor of the left vocal cord (again, right of photo) has melted away. Note that the mucositis is generalized, and not necessarily focal to the area of tumor sloughing.

Vocal cord cancer, 2 months after radiotherapy (6 of 7)

Same patient, now two months after the end of radiotherapy. All of the visible tumor is gone, and voice is very good. Small anterior web. Compare with photo 1 of this series.

Vocal cord cancer, 2 months after radiotherapy (6 of 7)

Same patient, now two months after the end of radiotherapy. All of the visible tumor is gone, and voice is very good. Small anterior web. Compare with photo 1 of this series.

Vocal cord cancer, 2 months after radiotherapy (7 of 7)

Phonation. Compare with photo 3 of this series.

Vocal cord cancer, 2 months after radiotherapy (7 of 7)

Phonation. Compare with photo 3 of this series.

Cancer, HPV Subtype 16, Before and After Radiation

Cancer: HPV Subtype 16 (1 of 5)

Cancer, in a patient with HPV subtype 16. The divot and blood seen on the left vocal cord (right of image) are the result of a biopsy performed elsewhere (not by BVI physician) earlier the same day as this examination.

Cancer: HPV Subtype 16 (1 of 5)

Cancer, in a patient with HPV subtype 16. The divot and blood seen on the left vocal cord (right of image) are the result of a biopsy performed elsewhere (not by BVI physician) earlier the same day as this examination.

Cancer: HPV Subtype 16, after radiation therapy (3 of 5)

Six weeks after the end of radiation therapy, the tumor is no longer seen. However, part of the left cord (right of image) is missing, due to sloughing of the tumor that had eaten away part of the cord’s normal tissue.

Cancer: HPV Subtype 16, after radiation therapy (3 of 5)

Six weeks after the end of radiation therapy, the tumor is no longer seen. However, part of the left cord (right of image) is missing, due to sloughing of the tumor that had eaten away part of the cord’s normal tissue.

Cancer: HPV Subtype 16, after radiation therapy (4 of 5)

Phonation. Strobe light, open phase of vibration, shows that the margin of the left cord (right of image) is at a lower level than the right’s, due to loss of some of the bulk of the cord where the tumor died and sloughed away.

Cancer: HPV Subtype 16, after radiation therapy (4 of 5)

Phonation. Strobe light, open phase of vibration, shows that the margin of the left cord (right of image) is at a lower level than the right’s, due to loss of some of the bulk of the cord where the tumor died and sloughed away.

Cancer: HPV Subtype 16, after radiation therapy (5 of 5)

Strobe light, closed phase of vibration. The more normal right cord (left of image) unsuccessfully attempts to reach the left cord’s residual upper surface mucosa. Voice is functional but hoarse.

Cancer: HPV Subtype 16, after radiation therapy (5 of 5)

Strobe light, closed phase of vibration. The more normal right cord (left of image) unsuccessfully attempts to reach the left cord’s residual upper surface mucosa. Voice is functional but hoarse.

Pre-and 1 Week Post-removal Vocal Nodules

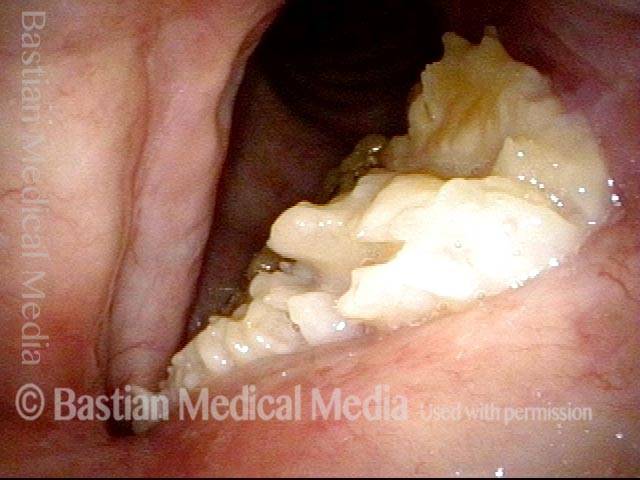

Verrucous carcinoma (1 of 5)

Verrucous carcinoma, left vocal cord, persistent after radiotherapy elsewhere, in a patient unable to undergo general anesthesia due to severe lung disease.

Verrucous carcinoma (1 of 5)

Verrucous carcinoma, left vocal cord, persistent after radiotherapy elsewhere, in a patient unable to undergo general anesthesia due to severe lung disease.

During voicing (2 of 5)

Can be seen even during voicing.

During voicing (2 of 5)

Can be seen even during voicing.

After laser treatment (3 of 5)

After several Thulium Laser ablations, using topical and injected local anesthesia, with patient sitting in examination chair, thereby avoiding general anesthesia.

After laser treatment (3 of 5)

After several Thulium Laser ablations, using topical and injected local anesthesia, with patient sitting in examination chair, thereby avoiding general anesthesia.

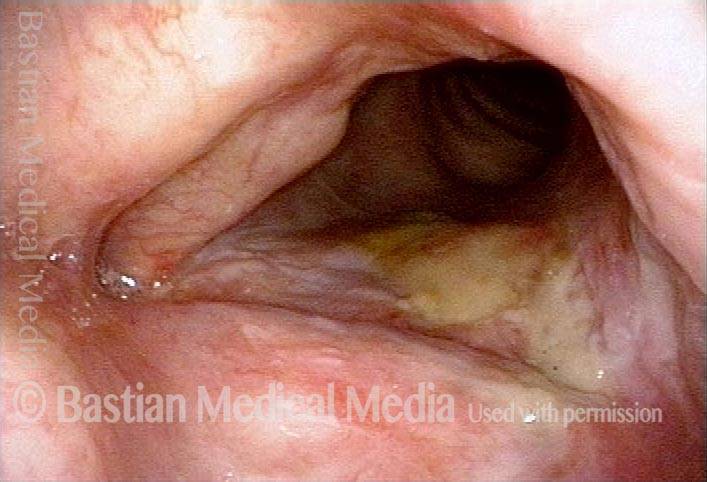

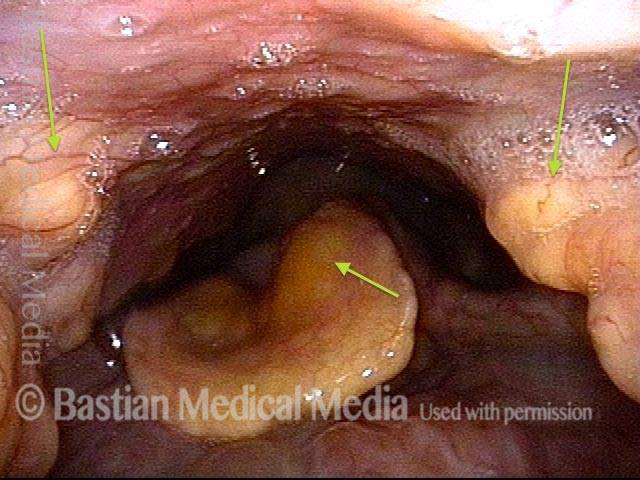

Mucus remains several weeks after laser treatment (4 of 5)

Approximately six weeks later, durable resolution of tumor. Yellow material is mucus.

Mucus remains several weeks after laser treatment (4 of 5)

Approximately six weeks later, durable resolution of tumor. Yellow material is mucus.

Much improvement several weeks after laser treatment (5 of 5)

During voicing. Arytenoid moves, but much of membranous vocal cord has been ablated as intended.

Much improvement several weeks after laser treatment (5 of 5)

During voicing. Arytenoid moves, but much of membranous vocal cord has been ablated as intended.

For more info: Cancer

Capillary Ectasia:

Capillary Ectasia, before and after Laser Coagulation

Capillary ectasia (1 of 7)

Abducted, breathing position, standard light. This is a vascular abnormality and not a polyp. We use the term “capillary lake.”

Capillary ectasia (1 of 7)

Abducted, breathing position, standard light. This is a vascular abnormality and not a polyp. We use the term “capillary lake.”

Capillary ectasia (2 of 7)

Pre-phonatory instant, standard light.

Capillary ectasia (2 of 7)

Pre-phonatory instant, standard light.

Capillary ectasia (3 of 7)

Strobe light, open phase of vibration. Mucus is consistent with the patient’s known acid reflux laryngitis.

Capillary ectasia (3 of 7)

Strobe light, open phase of vibration. Mucus is consistent with the patient’s known acid reflux laryngitis.

Closed phase (4 of 7)

Strobe light, closed phase of vibration.

Closed phase (4 of 7)

Strobe light, closed phase of vibration.

Capillary ectasia, after laser coagulation (5 of 7)

Abducted breathing position, standard light, some weeks after pulsed-KTP laser coagulation of the dilated capillaries, which are no longer visible.

Capillary ectasia, after laser coagulation (5 of 7)

Abducted breathing position, standard light, some weeks after pulsed-KTP laser coagulation of the dilated capillaries, which are no longer visible.

Capillary ectasia, after laser coagulation (6 of 7)

Same view, but under narrow-band illumination.

Capillary ectasia, after laser coagulation (6 of 7)

Same view, but under narrow-band illumination.

After laser coagulation (7 of 7)

Prephonatory instant, narrow-band illumination.

After laser coagulation (7 of 7)

Prephonatory instant, narrow-band illumination.

Capillary ectasia (1 of 3)

Bilateral capillary ectasia, made to stand out with the help of narrow-band illumination.

Capillary ectasia (1 of 3)

Bilateral capillary ectasia, made to stand out with the help of narrow-band illumination.

Capillary ectasia, right after laser coagulation (2 of 3)

At the conclusion of pulsed-KTP laser coagulation, performed in a videoendoscopy procedure room with patient awake and sitting in a chair.

Capillary ectasia, right after laser coagulation (2 of 3)

At the conclusion of pulsed-KTP laser coagulation, performed in a videoendoscopy procedure room with patient awake and sitting in a chair.

Capillary ectasia, 6 weeks after laser coagulation (3 of 3)

Six weeks later; the capillaries have vanished, as expected.

Capillary ectasia, 6 weeks after laser coagulation (3 of 3)

Six weeks later; the capillaries have vanished, as expected.

Capillary Ectasia and Hemorrhagic Polyp, before and after Treatment

Capillary ectasia and hemorrhagic polyp (1 of 4)

Open phase of vibration, strobe light.

Capillary ectasia and hemorrhagic polyp (1 of 4)

Open phase of vibration, strobe light.

Capillary ectasia and hemorrhagic polyp (2 of 4)

Partially closed phase of vibration, strobe light.

Capillary ectasia and hemorrhagic polyp (2 of 4)

Partially closed phase of vibration, strobe light.

Capillary ectasia and hemorrhagic polyp, after treatment (3 of 4)

Abducted breathing position after vocal cord microsurgery, standard light. Note that the right cord is normalized, the capillary ectasia on the left is smaller, but persists in spite of spot-coagulation. A simple pulsed-KTP laser procedure in the videoendoscopy procedure room abolished this residual lesion.

Capillary ectasia and hemorrhagic polyp, after treatment (3 of 4)

Abducted breathing position after vocal cord microsurgery, standard light. Note that the right cord is normalized, the capillary ectasia on the left is smaller, but persists in spite of spot-coagulation. A simple pulsed-KTP laser procedure in the videoendoscopy procedure room abolished this residual lesion.

Capillary ectasia and hemorrhagic polyp, after treatment (4 of 4)

Pre-phonatory instant, standard light, showing excellent match. Oscillatory ability entirely normal into extreme upper range in this professional singer.

Capillary ectasia and hemorrhagic polyp, after treatment (4 of 4)

Pre-phonatory instant, standard light, showing excellent match. Oscillatory ability entirely normal into extreme upper range in this professional singer.

For more info: Capillary ectasia

RRP:

Papillomas, HPV Subtype 11, before and after Removal

Papillomas: HPV Subtype 11 (1 of 4)

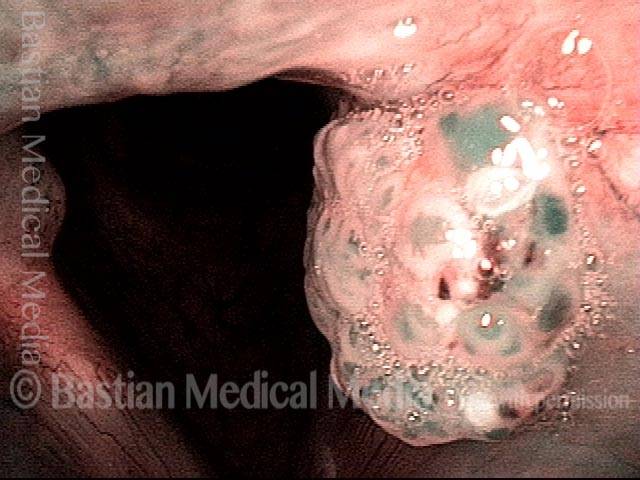

Papillomas at posterior vocal cords, with left side (right of image) much larger than right. This patient has HPV subtype 11.

Papillomas: HPV Subtype 11 (1 of 4)

Papillomas at posterior vocal cords, with left side (right of image) much larger than right. This patient has HPV subtype 11.

Papillomas: HPV Subtype 11 (2 of 4)

Closer view, under narrow band illumination, which accentuates the vascular pattern.

Papillomas: HPV Subtype 11 (2 of 4)

Closer view, under narrow band illumination, which accentuates the vascular pattern.

Papillomas, removed: HPV Subtype 11 (3 of 4)

Two weeks after microsurgical removal, cidofovir injection, and return of normal voice.

Papillomas, removed: HPV Subtype 11 (3 of 4)

Two weeks after microsurgical removal, cidofovir injection, and return of normal voice.

Papillomas, removed: HPV Subtype 11 (4 of 4)

Closer view of left posterior vocal cord, narrow band illumination. Notice that there are a few dot-like vascular marks. These are typical of HPV effect, and may presage recurrence.

Papillomas, removed: HPV Subtype 11 (4 of 4)

Closer view of left posterior vocal cord, narrow band illumination. Notice that there are a few dot-like vascular marks. These are typical of HPV effect, and may presage recurrence.

Lesions and Papillomas of HPV, Before and After Removal and Adjuvant Injection

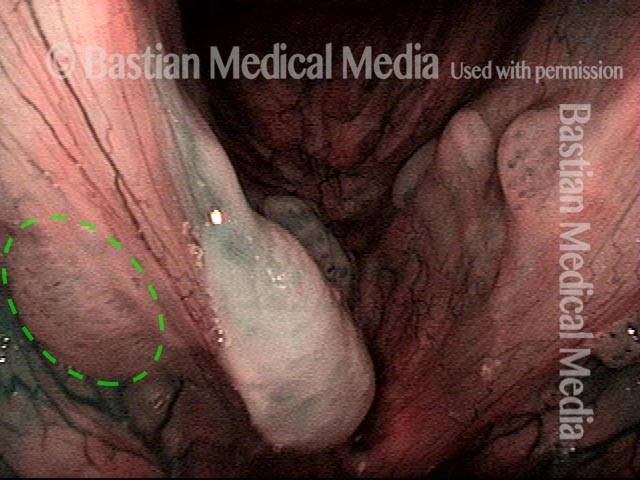

Lesions and papillomas of HPV subtype? (1 of 8)

At initial diagnosis, as yet untyped for HPV. Multi-focal lesions on both vocal cords.

Lesions and papillomas of HPV subtype? (1 of 8)

At initial diagnosis, as yet untyped for HPV. Multi-focal lesions on both vocal cords.

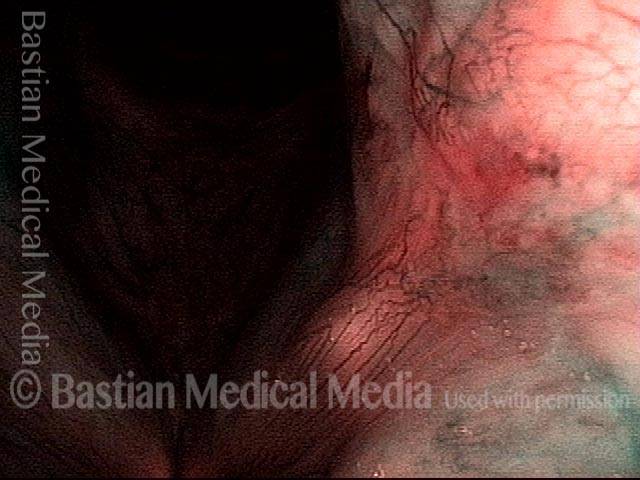

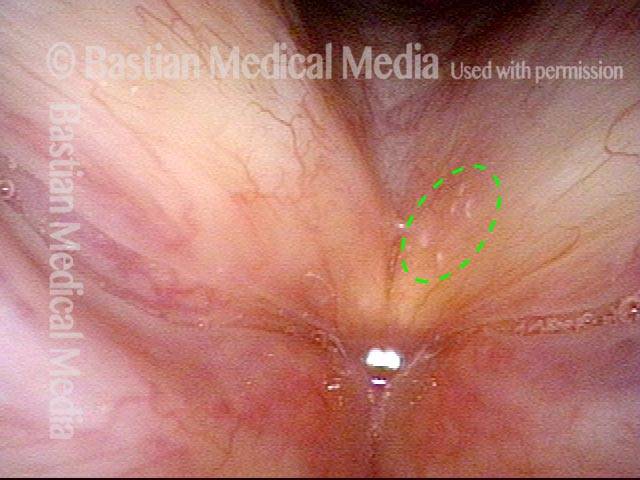

Subtle lesion (2 of 8)

Narrow-band illumination and a different viewing angle better reveal the more subtle lesion on the upper surface of the right cord (dotted circle).

Subtle lesion (2 of 8)

Narrow-band illumination and a different viewing angle better reveal the more subtle lesion on the upper surface of the right cord (dotted circle).

Open phase (3 of 8)

Strobe light, open phase of vibration, showing mismatch.

Open phase (3 of 8)

Strobe light, open phase of vibration, showing mismatch.

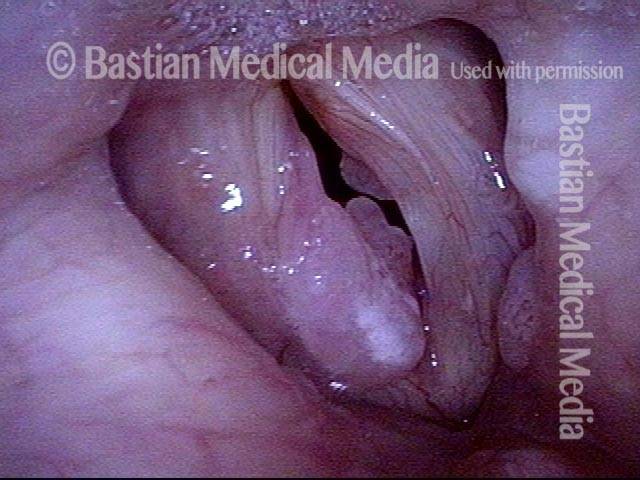

1 week after removal (4 of 8)

One week after removal of papillomas, voice is dramatically restored. Strobe light, open phase of vibration. Compare with photo 3.

1 week after removal (4 of 8)

One week after removal of papillomas, voice is dramatically restored. Strobe light, open phase of vibration. Compare with photo 3.

1 week after removal (5 of 8)

Strobe illumination, closed phase. Even in falsetto, oscillatory ability is preserved due to the precise and superficial removal of the papillomas.

1 week after removal (5 of 8)

Strobe illumination, closed phase. Even in falsetto, oscillatory ability is preserved due to the precise and superficial removal of the papillomas.

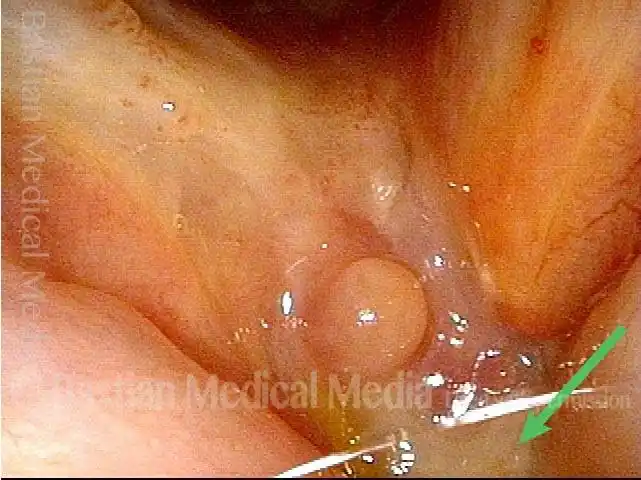

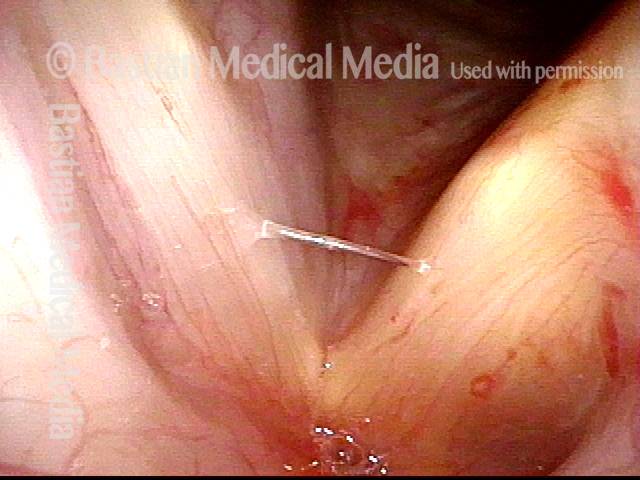

Injecting adjuvant (6 of 8)

At three weeks after removal, the patient regards his voice as normal. The patient has neither lesion nor vascular change to suggest any residual or recurrent lesion. Needle in photo (arrow) positioned to inject adjuvant medication in attempt to prevent recurrence. This procedure is done in a voice lab under topical anesthesia, not the operating room.

Injecting adjuvant (6 of 8)

At three weeks after removal, the patient regards his voice as normal. The patient has neither lesion nor vascular change to suggest any residual or recurrent lesion. Needle in photo (arrow) positioned to inject adjuvant medication in attempt to prevent recurrence. This procedure is done in a voice lab under topical anesthesia, not the operating room.

After injecting adjuvant (7 of 8)

After both cords have been “inflated” with adjuvant medication. Note the convex, slightly blanched vocal cord margins, due to superficial infiltration of the medication.

After injecting adjuvant (7 of 8)

After both cords have been “inflated” with adjuvant medication. Note the convex, slightly blanched vocal cord margins, due to superficial infiltration of the medication.

After final adjuvant injection (8 of 8)

Nearly a month later, immediately after the third and final adjuvant injection (hence the blood below the vocal cords). The patient again regarded his voice as completely normal. No sign at this early point of recurrence of papillomas or other HPV lesions. Patients with focal disease as seen in photo 1 of this series not infrequently go into long-term remission or “cure,” though it may be impossible to discern the relative roles of surgery, adjuvants, and the patient’s immune system.

After final adjuvant injection (8 of 8)

Nearly a month later, immediately after the third and final adjuvant injection (hence the blood below the vocal cords). The patient again regarded his voice as completely normal. No sign at this early point of recurrence of papillomas or other HPV lesions. Patients with focal disease as seen in photo 1 of this series not infrequently go into long-term remission or “cure,” though it may be impossible to discern the relative roles of surgery, adjuvants, and the patient’s immune system.

Papillomas, HPV Subtype 6, before and after Removal

Papillomas: HPV Subtype 6 (1 of 4)

Papilloma, left vocal cord (right of image), standard light. Voice is grossly hoarse. This patient has HPV subtype 6.

Papillomas: HPV Subtype 6 (1 of 4)

Papilloma, left vocal cord (right of image), standard light. Voice is grossly hoarse. This patient has HPV subtype 6.

Papillomas: HPV Subtype 6 (2 of 4)

Same lesion, under narrow band illumination.

Papillomas: HPV Subtype 6 (2 of 4)

Same lesion, under narrow band illumination.

Papillomas, removed: HPV Subtype 6 (3 of 4)

After removal and cidofovir injection, normalized larynx. Voice is normal.

Papillomas, removed: HPV Subtype 6 (3 of 4)

After removal and cidofovir injection, normalized larynx. Voice is normal.

Papillomas, removed: HPV Subtype 6 (4 of 4)

Same view, under narrow band illumination.

Papillomas, removed: HPV Subtype 6 (4 of 4)

Same view, under narrow band illumination.

For more info: Recurrent Respiratory Papillomatosis

Vocal Cord Paralysis/paresis:

TA-only Paresis before and after Voice Gel Injection

TA weakness, intact LCA + PCA (1 of 5)

TA weakness indicated by bowed margin and “spaghetti-linguini” difference between the cords. Medial turning of vocal process (arrow) suggests intact LCA; abducted position suggests intact PCA function. Blood is from cricothyroid membrane puncture to instill topical anesthesia.

TA weakness, intact LCA + PCA (1 of 5)

TA weakness indicated by bowed margin and “spaghetti-linguini” difference between the cords. Medial turning of vocal process (arrow) suggests intact LCA; abducted position suggests intact PCA function. Blood is from cricothyroid membrane puncture to instill topical anesthesia.

Prephonatory instant (2 of 5)

Before voice gel injection at prephonatory instant. Wasting of left cord (right of photo), and capacious ventricle on the left (right of photo) clearly evident.

Prephonatory instant (2 of 5)

Before voice gel injection at prephonatory instant. Wasting of left cord (right of photo), and capacious ventricle on the left (right of photo) clearly evident.

Gel injection (3 of 5)

At beginning of voice gel injection (needle at white arrow).

Gel injection (3 of 5)

At beginning of voice gel injection (needle at white arrow).

Straight vocal cord margin (4 of 5)

At conclusion of voice gel, note straight left cord margin (right of photo). Compare with photos 1 and 3.

Straight vocal cord margin (4 of 5)

At conclusion of voice gel, note straight left cord margin (right of photo). Compare with photos 1 and 3.

Phonation (5 of 5)

Phonation after injection complete. Voice dramatically strengthened. Compare with photo 2.

Phonation (5 of 5)

Phonation after injection complete. Voice dramatically strengthened. Compare with photo 2.

Paresis, TA-only: before and after an Implant

Paresis, TA-only (1 of 5)

During abducted breathing position, note the atrophy of the left cord (right of image), mild margin convexity, and the capacious ventricle (at bottom-right), all of which indicate TA paresis. The cord abducts fully, demonstrating intact PCA fuction. LCA function cannot be determined in this view.

Paresis, TA-only (1 of 5)

During abducted breathing position, note the atrophy of the left cord (right of image), mild margin convexity, and the capacious ventricle (at bottom-right), all of which indicate TA paresis. The cord abducts fully, demonstrating intact PCA fuction. LCA function cannot be determined in this view.

Paresis, TA-only (2 of 5)

Adducted position for phonation, with phonatory blurring as seen under standard light. LCA appears to be functioning, as indicated by the strict anterior-posterior direction of the left vocal process (right of image), just the same as for the right. This accounts for quite good approximation of the cords. The ventricle again appears capacious (dotted oval). Based upon these first two photos, we can surmise that this is a TA-only paresis.

Paresis, TA-only (2 of 5)

Adducted position for phonation, with phonatory blurring as seen under standard light. LCA appears to be functioning, as indicated by the strict anterior-posterior direction of the left vocal process (right of image), just the same as for the right. This accounts for quite good approximation of the cords. The ventricle again appears capacious (dotted oval). Based upon these first two photos, we can surmise that this is a TA-only paresis.

Paresis, TA-only (3 of 5)

Under strobe light, showing increased amplitude of vibration of the left cord (right of image). This finding suggests in yet another way that the TA muscle is paralyzed.

Paresis, TA-only (3 of 5)

Under strobe light, showing increased amplitude of vibration of the left cord (right of image). This finding suggests in yet another way that the TA muscle is paralyzed.

Paresis, TA-only: after implant is placed (4 of 5)

After placement of an implant into the left cord (right of image). Note the bulging of that cord and straightening of the cord's margin, and also that the ventricle on that side no longer appears capacious. Compare with photo 1.

Paresis, TA-only: after implant is placed (4 of 5)

After placement of an implant into the left cord (right of image). Note the bulging of that cord and straightening of the cord's margin, and also that the ventricle on that side no longer appears capacious. Compare with photo 1.

Paresis, TA-only: after implant is placed (5 of 5)

Under strobe illumination. Note that the lateral excursion of both cords is the same, since the left cord (right of image) is now less flaccid. Compare with photo 3

Paresis, TA-only: after implant is placed (5 of 5)

Under strobe illumination. Note that the lateral excursion of both cords is the same, since the left cord (right of image) is now less flaccid. Compare with photo 3

Vocal Cord Paralysis, Before and After Medialization

Vocal cord paralysis: before medialization (1 of 12)

A classic example of “spaghetti-linguine” vocal cords, here in breathing position. The “linguine” cord (left of image) is normal; the “spaghetti” cord (right of image) is paralyzed, likely since birth. On the paralyzed side, notice the deep and broad ventricle, mild bowing of the margin of the cord, and reduced width of the upper surface of the cord (“spaghetti”-like), as compared with the non-paralyzed side.

Vocal cord paralysis: before medialization (1 of 12)

A classic example of “spaghetti-linguine” vocal cords, here in breathing position. The “linguine” cord (left of image) is normal; the “spaghetti” cord (right of image) is paralyzed, likely since birth. On the paralyzed side, notice the deep and broad ventricle, mild bowing of the margin of the cord, and reduced width of the upper surface of the cord (“spaghetti”-like), as compared with the non-paralyzed side.

Vocal cord paralysis: before medialization (2 of 12)

Phonation, more distant view, under standard light. Notice the considerable gap between the vocal cords. This gap correlates with the patient’s weak and air-wasting voice quality.

Vocal cord paralysis: before medialization (2 of 12)

Phonation, more distant view, under standard light. Notice the considerable gap between the vocal cords. This gap correlates with the patient’s weak and air-wasting voice quality.

Vocal cord paralysis: before medialization (3 of 12)

Open phase of vibration, under strobe light. The paralyzed cord (right of image) has a much increased amplitude (lateral or outward excursion) and exaggerated bowing, due to its flaccidity.

Vocal cord paralysis: before medialization (3 of 12)

Open phase of vibration, under strobe light. The paralyzed cord (right of image) has a much increased amplitude (lateral or outward excursion) and exaggerated bowing, due to its flaccidity.

Vocal cord paralysis: before medialization (4 of 12)

“Closed” phase of vibration, which is of course not closed at all, because the paralyzed cord (right of image) cannot come fully to the midline.

Vocal cord paralysis: before medialization (4 of 12)

“Closed” phase of vibration, which is of course not closed at all, because the paralyzed cord (right of image) cannot come fully to the midline.

Vocal cord paralysis: 1 week after medialization (5 of 12)

One week after surgical medialization of the paralyzed cord (right of image), using a silastic implant buried deeply within the cord. Notice that the ventricle is no longer capacious, and the free margin is no longer bowed. Furthermore, in contrast with photo 1 of this series, the “spaghetti-linguine” description of these vocal cords is no longer apt.

Vocal cord paralysis: 1 week after medialization (5 of 12)

One week after surgical medialization of the paralyzed cord (right of image), using a silastic implant buried deeply within the cord. Notice that the ventricle is no longer capacious, and the free margin is no longer bowed. Furthermore, in contrast with photo 1 of this series, the “spaghetti-linguine” description of these vocal cords is no longer apt.

Vocal cord paralysis: 1 week after medialization (6 of 12)

Phonation, under standard light. The gap between the cords is no longer seen (compare with photo 2), and the patient's spontaneous speaking voice sounds normal. She can recruit loudness effectively without any luffing or observable weakness.

Vocal cord paralysis: 1 week after medialization (6 of 12)

Phonation, under standard light. The gap between the cords is no longer seen (compare with photo 2), and the patient's spontaneous speaking voice sounds normal. She can recruit loudness effectively without any luffing or observable weakness.

Vocal cord paralysis: 1 week after medialization (7 of 12)

Open phase of vibration, under strobe light. The lateral or outward excursion of the paralyzed cord (right of image) is now similar to that of the non-paralyzed cord. Compare with photo 3.

Vocal cord paralysis: 1 week after medialization (7 of 12)

Open phase of vibration, under strobe light. The lateral or outward excursion of the paralyzed cord (right of image) is now similar to that of the non-paralyzed cord. Compare with photo 3.

Vocal cord paralysis: 1 week after medialization (8 of 12)

The closed phase of vibration is much more closed than preoperatively. Compare with photo 4.

Vocal cord paralysis: 1 week after medialization (8 of 12)

The closed phase of vibration is much more closed than preoperatively. Compare with photo 4.

Vocal cord paralysis: 5 months after medialization (9 of 12)

Five months after medialization. Compare this partially abducted position with photos 1 and 5 of this series.

Vocal cord paralysis: 5 months after medialization (9 of 12)

Five months after medialization. Compare this partially abducted position with photos 1 and 5 of this series.

Vocal cord paralysis: 5 months after medialization (10 of 12)

Phonation, under standard light, showing vibratory blur. Compare with photos 2 and 6 of this series.

Vocal cord paralysis: 5 months after medialization (10 of 12)

Phonation, under standard light, showing vibratory blur. Compare with photos 2 and 6 of this series.

Vocal cord paralysis: 5 months after medialization (11 of 12)

Open phase of vibration, under strobe light. As in photo 7 of this series, and in contrast to photo 3, the implant does not permit the paralyzed cord (right of image) to “buckle” laterally, or outward. If anything, the vibratory excursion of the non-paralyzed (and un-implanted) cord is greater than that of the paralyzed, implanted cord.

Vocal cord paralysis: 5 months after medialization (11 of 12)

Open phase of vibration, under strobe light. As in photo 7 of this series, and in contrast to photo 3, the implant does not permit the paralyzed cord (right of image) to “buckle” laterally, or outward. If anything, the vibratory excursion of the non-paralyzed (and un-implanted) cord is greater than that of the paralyzed, implanted cord.

Vocal cord paralysis: 5 months after medialization (12 of 12

The closed phase of vibration is now virtually normal, similar to photo 8 and in contrast with photo 4.

Vocal cord paralysis: 5 months after medialization (12 of 12

The closed phase of vibration is now virtually normal, similar to photo 8 and in contrast with photo 4.

Paresis, TA + LCA, before and after Placement of an Implant

Paresis, TA + LCA (1 of 6)

Distant view shows lesser normal-appearing abduction left cord (right of image) during breathing, suggesting that the left posterior cricoarytenoid muscle is working. Note the lesser bulk of the left vocal cord as compared with the right, although this is subtle at this viewing distance.

Paresis, TA + LCA (1 of 6)

Distant view shows lesser normal-appearing abduction left cord (right of image) during breathing, suggesting that the left posterior cricoarytenoid muscle is working. Note the lesser bulk of the left vocal cord as compared with the right, although this is subtle at this viewing distance.

Paresis, TA + LCA (2 of 6)

At closer range, still in breathing position, one can see more easily the “linguine” of the right vocal cord (left of image) compared with the “spaghetti” and slight bowing of the left. These findings correlate with left thyroarytenoid (TA) muscle weakness and atrophy.

Paresis, TA + LCA (2 of 6)

At closer range, still in breathing position, one can see more easily the “linguine” of the right vocal cord (left of image) compared with the “spaghetti” and slight bowing of the left. These findings correlate with left thyroarytenoid (TA) muscle weakness and atrophy.

Paresis, TA + LCA (3 of 6)

In phonatory position under strobe light, the bowing of the left cord (right of image) is more evident, as is the lateral turning of the left vocal process, consistent with weakness of the left lateral cricoarytenoid (LCA) muscle. Lines denote the direction each vocal process is pointing.

Paresis, TA + LCA (3 of 6)

In phonatory position under strobe light, the bowing of the left cord (right of image) is more evident, as is the lateral turning of the left vocal process, consistent with weakness of the left lateral cricoarytenoid (LCA) muscle. Lines denote the direction each vocal process is pointing.

Paresis, TA + LCA: 1 week after implant is placed (4 of 6)

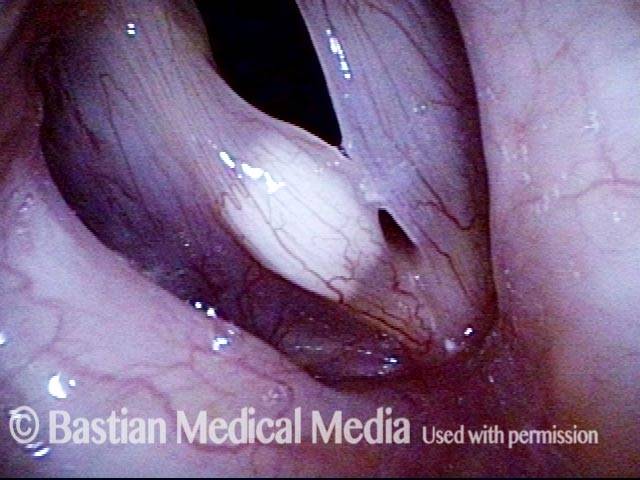

One week after placement of a large silastic implant into the left vocal cord (right of image). Notice the temporary eversion of the left ventricle, almost simulating a large polyp.

Paresis, TA + LCA: 1 week after implant is placed (4 of 6)

One week after placement of a large silastic implant into the left vocal cord (right of image). Notice the temporary eversion of the left ventricle, almost simulating a large polyp.

Paresis, TA + LCA: 3 months after implant is placed (5 of 6)

A few months later, fullness of left vocal cord (right of image) remains, but eversion / edema of ventricular mucosa has resolved. Compare with image 1.

Paresis, TA + LCA: 3 months after implant is placed (5 of 6)

A few months later, fullness of left vocal cord (right of image) remains, but eversion / edema of ventricular mucosa has resolved. Compare with image 1.

Paresis, TA + LCA: 3 months after implant is placed (6 of 6)

During phonation, much better closure (with markedly improved voice) but still slightly lateral turning of the left vocal process (right of image). Compare with image 3.

Paresis, TA + LCA: 3 months after implant is placed (6 of 6)

During phonation, much better closure (with markedly improved voice) but still slightly lateral turning of the left vocal process (right of image). Compare with image 3.

Paresis, TA + LCA, before and after Injection of Voice Gel

Paresis, TA + LCA (1 of 5)

Right vocal cord paresis (left of image). Note marked atrophy as compared with the left cord. Highly lateralized position denotes some persistent action of the right posterior cricoarytenoid muscle.

Paresis, TA + LCA (1 of 5)

Right vocal cord paresis (left of image). Note marked atrophy as compared with the left cord. Highly lateralized position denotes some persistent action of the right posterior cricoarytenoid muscle.

Paresis, TA + LCA (2 of 5)

Initiation of phonation. Note medical turning off left vocal process of arytenoid (right of image), and absent movement of the right vocal cord. Neither thyroarytenoid nor lateral cricoarytenoid muscles are innervated.

Paresis, TA + LCA (2 of 5)

Initiation of phonation. Note medical turning off left vocal process of arytenoid (right of image), and absent movement of the right vocal cord. Neither thyroarytenoid nor lateral cricoarytenoid muscles are innervated.

Paresis, TA + LCA: voice gel injection (3 of 5)

Immediately following injection of right vocal cord (left of image) with voice gel, with patient in videoendoscopy room chair, under topical anesthesia. Note bulging of right vocal cord.

Paresis, TA + LCA: voice gel injection (3 of 5)

Immediately following injection of right vocal cord (left of image) with voice gel, with patient in videoendoscopy room chair, under topical anesthesia. Note bulging of right vocal cord.

Paresis, TA + LCA: 1 month after voice gel injection (4 of 5)

A month later, showing plumping up of the right vocal cord (left of image) with voice gel. Vocal cord continues to abduct fully, due to functioning posterior branch of recurrent nerve, which innervates the posterior cricoarytenoid muscle.

Paresis, TA + LCA: 1 month after voice gel injection (4 of 5)

A month later, showing plumping up of the right vocal cord (left of image) with voice gel. Vocal cord continues to abduct fully, due to functioning posterior branch of recurrent nerve, which innervates the posterior cricoarytenoid muscle.

Paresis, TA + LCA: 1 month after voice gel injection (5 of 5)

Phonation. There is some movement to the midline due to the bilaterally innervated interarytenoid muscle. The lateral cricoarytenoid muscle is paralyzed, as seen in lateral turning of the vocal process. Voice is dramatically improved as compared with pre-injection. The voice gel will be expected to gradually absorb over three to nine months, during which time the anterior branch of the recurrent nerve may recover its function.

Paresis, TA + LCA: 1 month after voice gel injection (5 of 5)

Phonation. There is some movement to the midline due to the bilaterally innervated interarytenoid muscle. The lateral cricoarytenoid muscle is paralyzed, as seen in lateral turning of the vocal process. Voice is dramatically improved as compared with pre-injection. The voice gel will be expected to gradually absorb over three to nine months, during which time the anterior branch of the recurrent nerve may recover its function.

Voice Gel Injection for Vocal Cord Paralysis

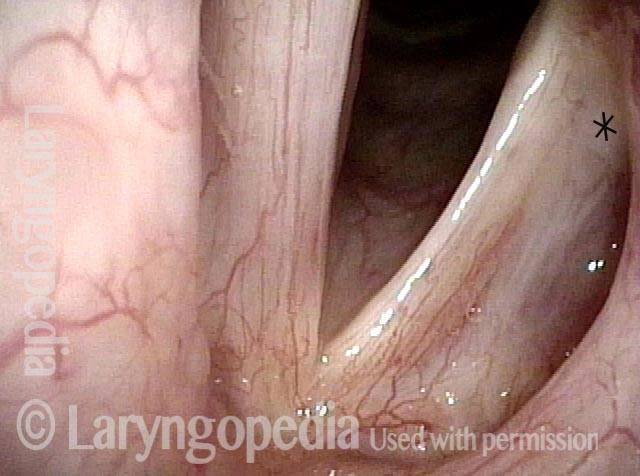

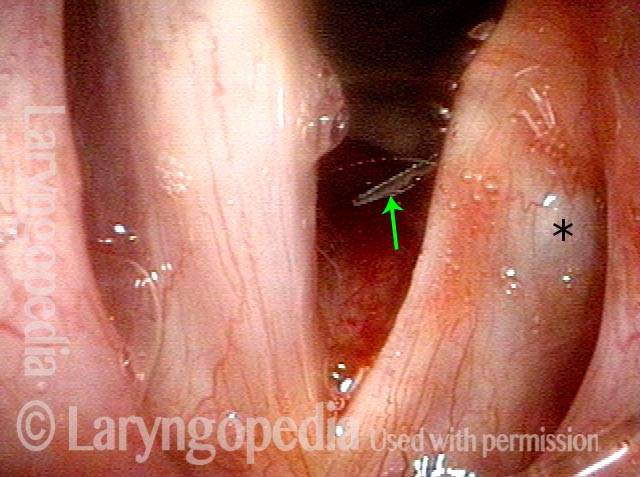

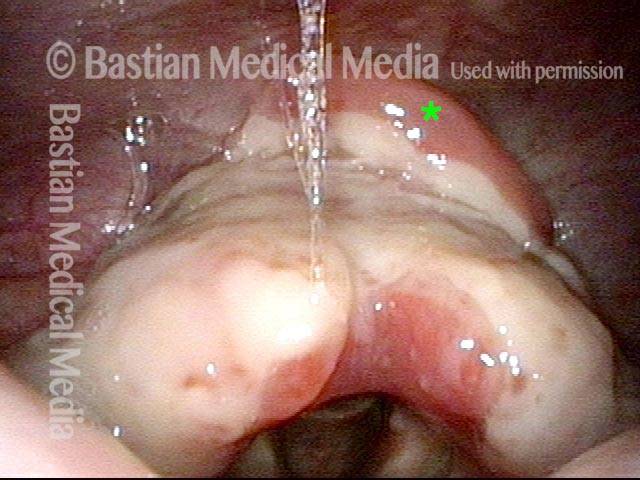

Left vocal cord paralysis (1 of 4)

This photo shows left vocal cord paralysis in the breathing position. Note the margin bowing, “spaghetti-linguini” difference in bulk, and capacious ventricle. Note: the * is for comparison with photo 3.

Left vocal cord paralysis (1 of 4)

This photo shows left vocal cord paralysis in the breathing position. Note the margin bowing, “spaghetti-linguini” difference in bulk, and capacious ventricle. Note: the * is for comparison with photo 3.

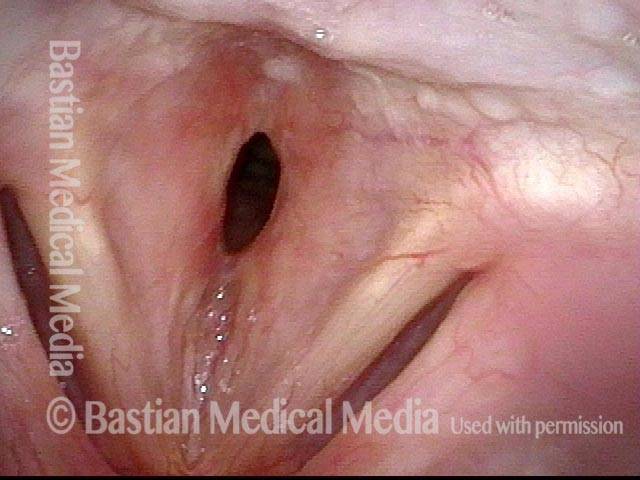

Voice-making position (2 of 4)

Here the paralysis is shown in the voice-making position. Note the lateral buckling of the left vocal cord (right of photo). This flaccidity and the gap between the vocal cords explain the patient’s breathy (air-wasting) voice quality.

Voice-making position (2 of 4)

Here the paralysis is shown in the voice-making position. Note the lateral buckling of the left vocal cord (right of photo). This flaccidity and the gap between the vocal cords explain the patient’s breathy (air-wasting) voice quality.

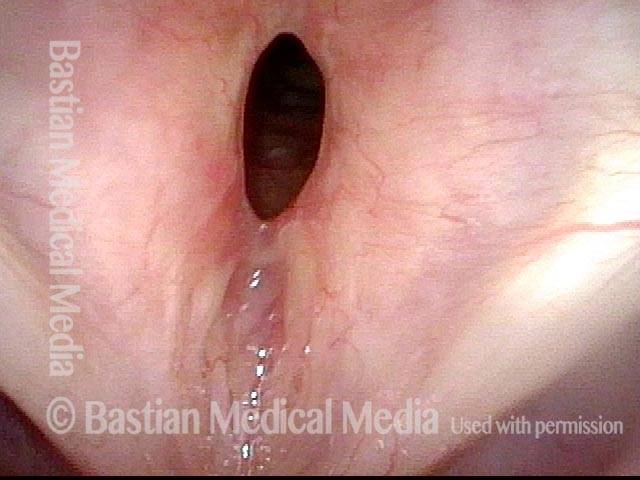

Voice gel injection (3 of 4)

This is the same patient at the beginning of voice gel injection. Needle at arrow coming from subglottis upwards and laterally. At * one can see the beginning of bulging in the posterior ventricle. The vocal cord also looks slightly shifted towards the midline. Compare with photo 1.

Voice gel injection (3 of 4)

This is the same patient at the beginning of voice gel injection. Needle at arrow coming from subglottis upwards and laterally. At * one can see the beginning of bulging in the posterior ventricle. The vocal cord also looks slightly shifted towards the midline. Compare with photo 1.

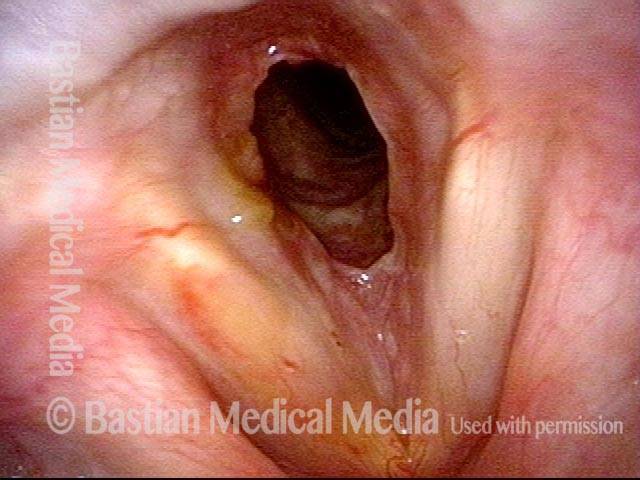

After voice gel injection (4 of 4)

Voice-making position after voice gel injection is complete and bulge in ventricle at * is more evident. Closure is much better; the voice is dramatically stronger and the air-wasting quality much less. Compare with photo 2.

After voice gel injection (4 of 4)

Voice-making position after voice gel injection is complete and bulge in ventricle at * is more evident. Closure is much better; the voice is dramatically stronger and the air-wasting quality much less. Compare with photo 2.

For more info: Paralysis or Paresis

Stenosis:

Subglottic Stenosis, before and after Dilation

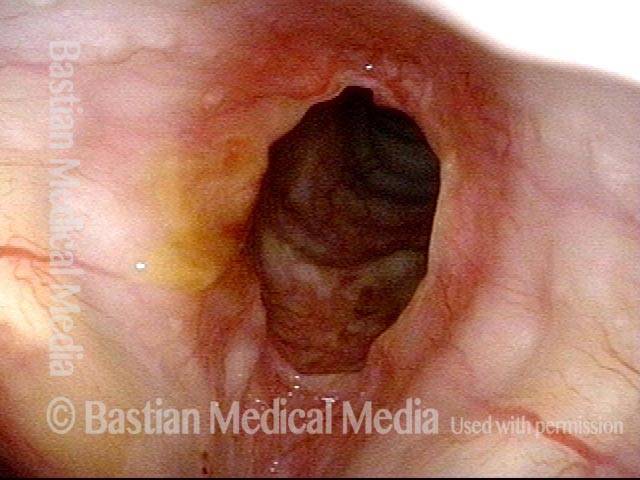

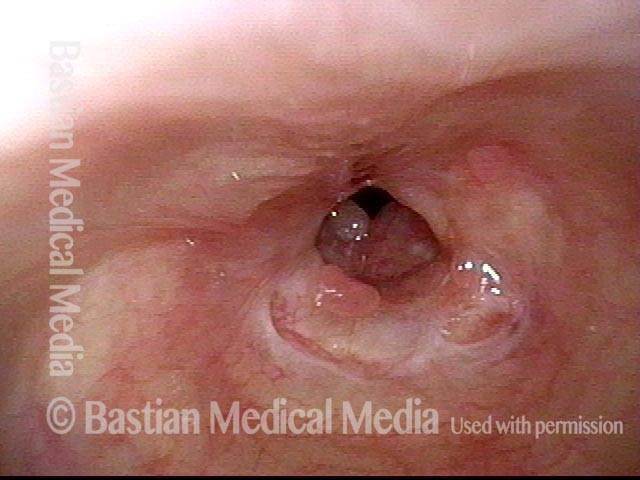

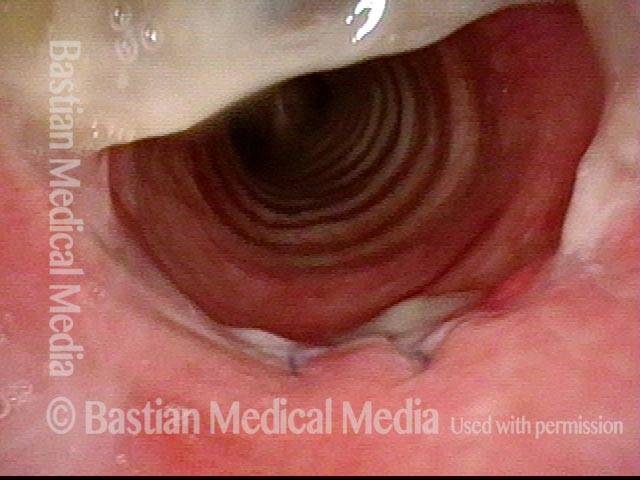

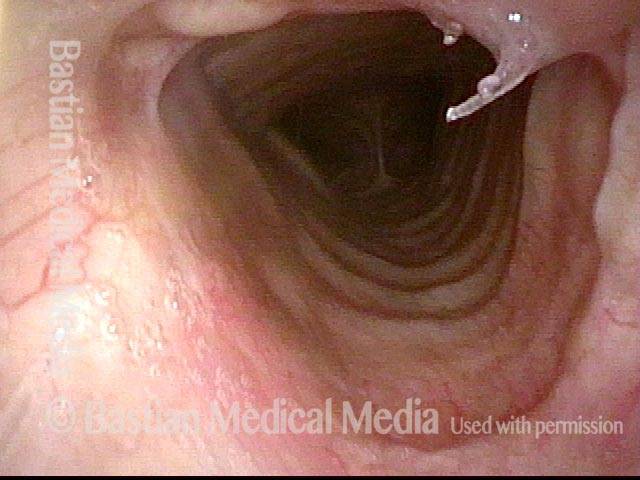

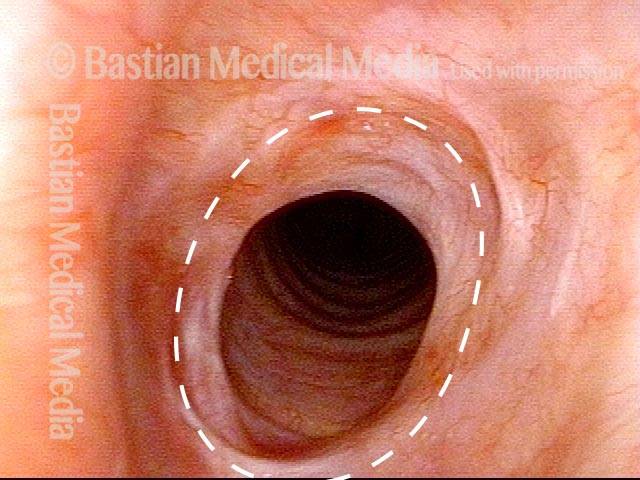

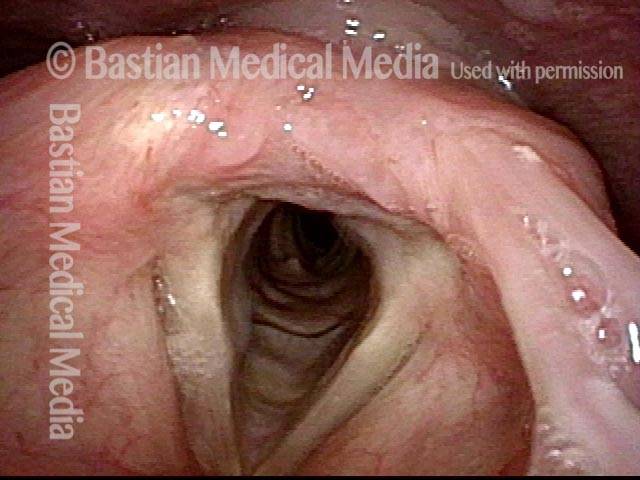

Subglottic stenosis (1 of 5)

Middle-aged woman with unexplained shortness of breath and noisy breathing, due to this idiopathic inflammatory and very high subglottic stenosis. The patient initially declined dilation due to her anxiety. She also had granularity of the nasal septum and a positive ANCA profile for Wegener’s granulomatosis.

Subglottic stenosis (1 of 5)

Middle-aged woman with unexplained shortness of breath and noisy breathing, due to this idiopathic inflammatory and very high subglottic stenosis. The patient initially declined dilation due to her anxiety. She also had granularity of the nasal septum and a positive ANCA profile for Wegener’s granulomatosis.

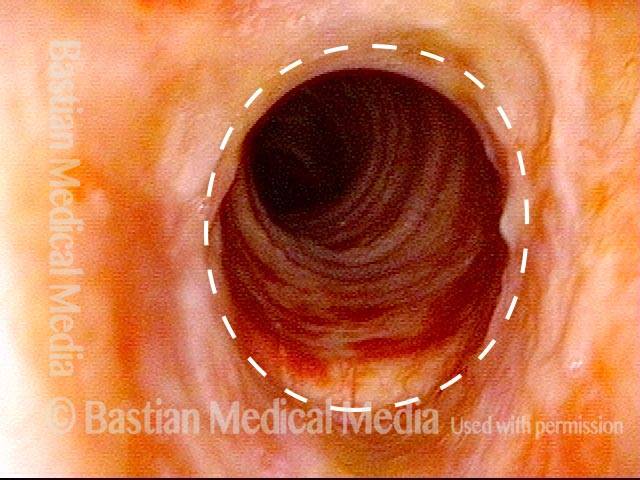

Subglottic stenosis, worsened (2 of 5)

Five months later, the symptoms became intolerable, and the stenosis was noted to be slightly narrower and with a greater posterior component. The patient agreed to dilation.

Subglottic stenosis, worsened (2 of 5)

Five months later, the symptoms became intolerable, and the stenosis was noted to be slightly narrower and with a greater posterior component. The patient agreed to dilation.

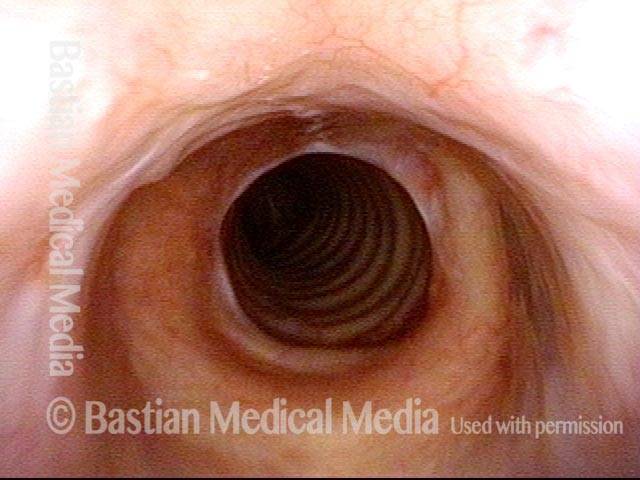

Subglottic stenosis, worsened (3 of 5)

Same exam as photo 2; this close-up view shows more clearly the inflammatory nature of this stenosis.

Subglottic stenosis, worsened (3 of 5)

Same exam as photo 2; this close-up view shows more clearly the inflammatory nature of this stenosis.

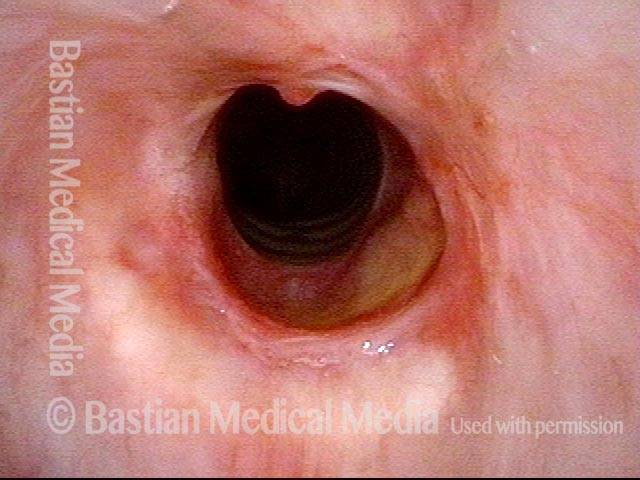

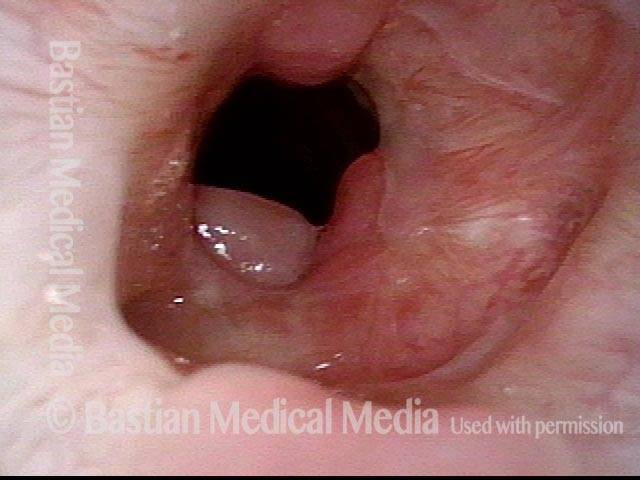

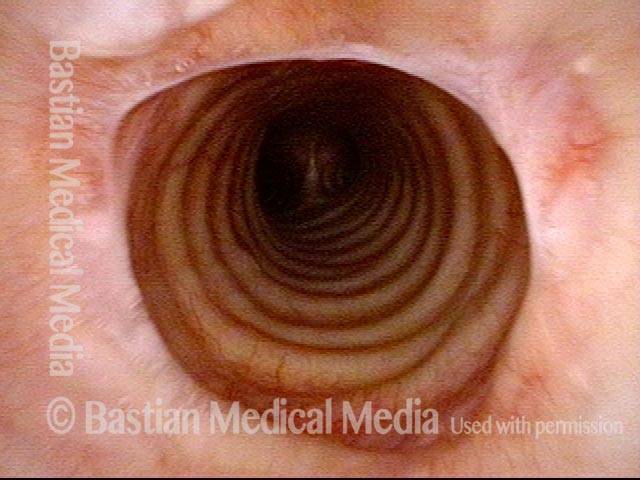

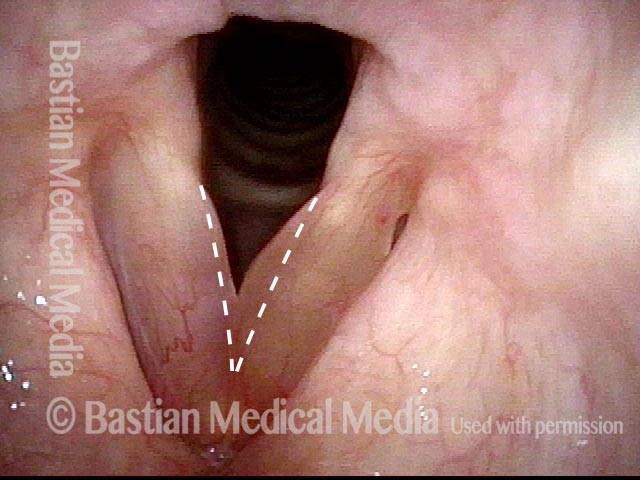

Subglottic stenosis, after dilation (4 of 5)

Five days after outpatient dilation, triamcinolone injection, and topical mitomycin C application. The patient’s symptoms have vanished, the harsh inspiratory noise is no longer heard, and the size of the airway, though still not normal, is more than doubled. Compare with photo 2 of this series.

Subglottic stenosis, after dilation (4 of 5)

Five days after outpatient dilation, triamcinolone injection, and topical mitomycin C application. The patient’s symptoms have vanished, the harsh inspiratory noise is no longer heard, and the size of the airway, though still not normal, is more than doubled. Compare with photo 2 of this series.

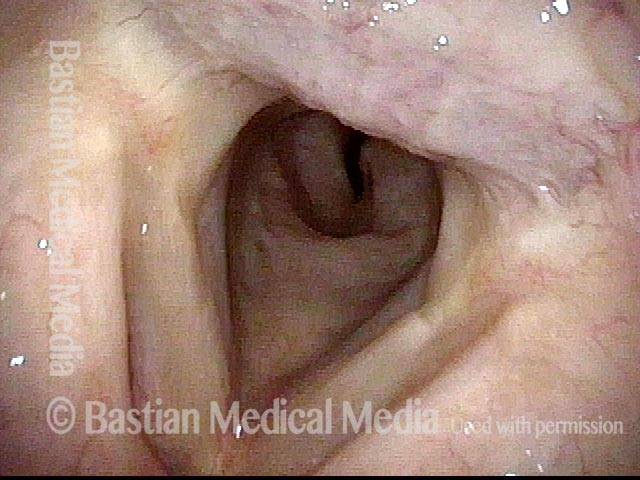

Subglottic stenosis, after dilation (5 of 5)

Same exam as photo 4, close-up view. Intensification of the inflammatory changes of this stenosis are expected so early after dilation. Compare size of the stenosis with photo 3 of this series.

Subglottic stenosis, after dilation (5 of 5)

Same exam as photo 4, close-up view. Intensification of the inflammatory changes of this stenosis are expected so early after dilation. Compare size of the stenosis with photo 3 of this series.

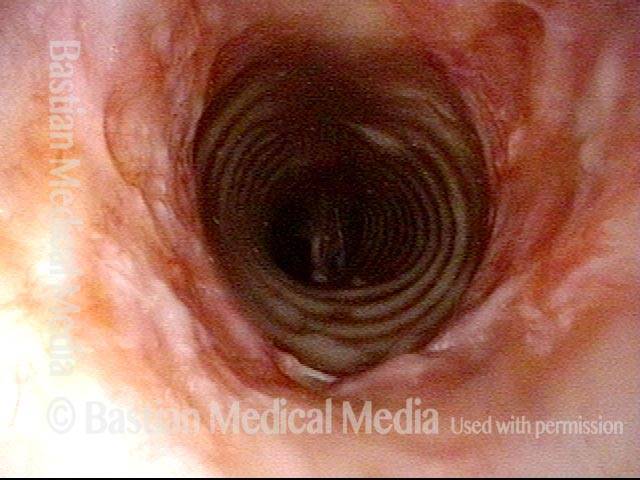

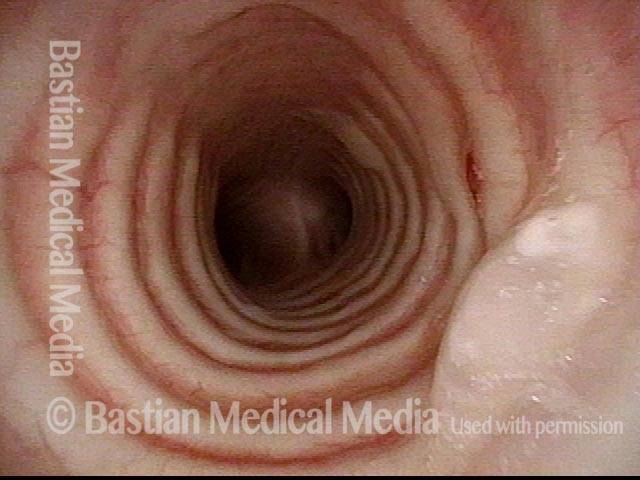

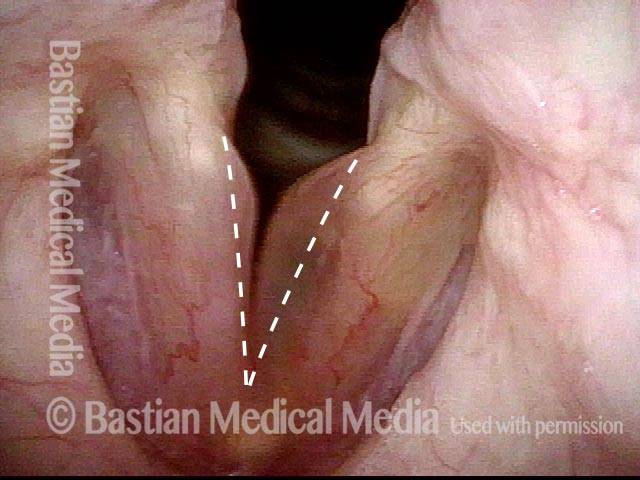

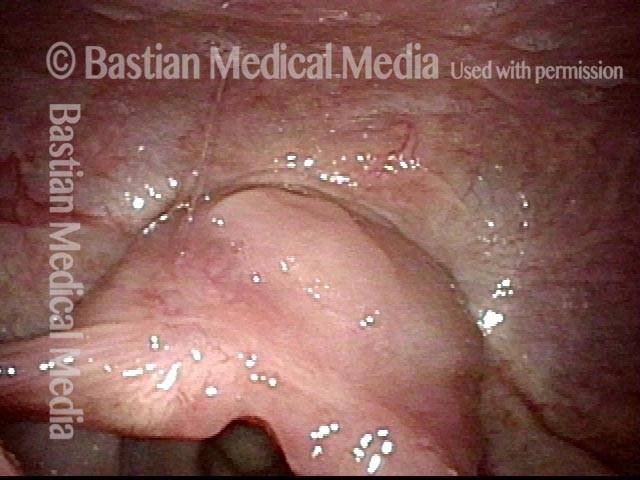

Subglottic stenosis, before dilation (1 of 2)

This individual has undergone at least a dozen prior dilations, each of which provides dramatic relief from noisy breathing and exercise intolerance. Here the patient is halfway to needing re-dilation, due to the typical inflammatory stenosis that is seen. Compare with photo 2.

Subglottic stenosis, before dilation (1 of 2)

This individual has undergone at least a dozen prior dilations, each of which provides dramatic relief from noisy breathing and exercise intolerance. Here the patient is halfway to needing re-dilation, due to the typical inflammatory stenosis that is seen. Compare with photo 2.

Subglottic stenosis, after dilation (2 of 2)

One week after one of this patient's dilations (with Kenalog injection and topical Mitomycin C), showing a dramatic widening of her airway; compare with photo 1. After a number of years, inflammatory lesions such as this sometimes "burn out," and the interval between dilations increases.

Subglottic stenosis, after dilation (2 of 2)

One week after one of this patient's dilations (with Kenalog injection and topical Mitomycin C), showing a dramatic widening of her airway; compare with photo 1. After a number of years, inflammatory lesions such as this sometimes "burn out," and the interval between dilations increases.

Tracheal Stenosis, before and after Tracheal Resection and Primary Reanastomosis