Injury, typically to the posterior part of both vocal cords, caused by an endotracheal tube1. An endotracheal tube may be used briefly during general anesthesia for surgery, but may be in place for much longer in persons suffering respiratory failure or neurological injury. When severe, the hallmark vocal phenomenology of intubation injury is breathy-pressed phonation.

Breathing Tube Injury may Correlate with Side of Mouth

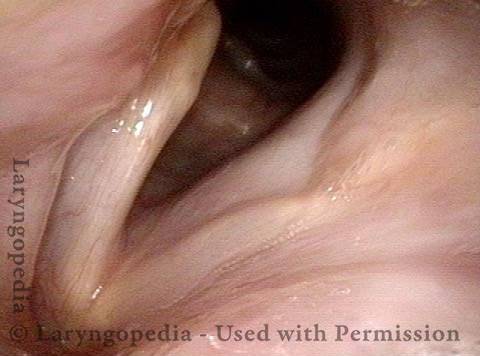

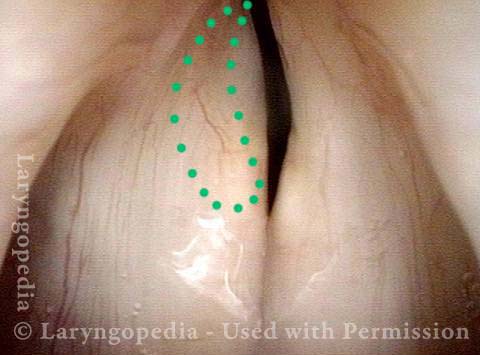

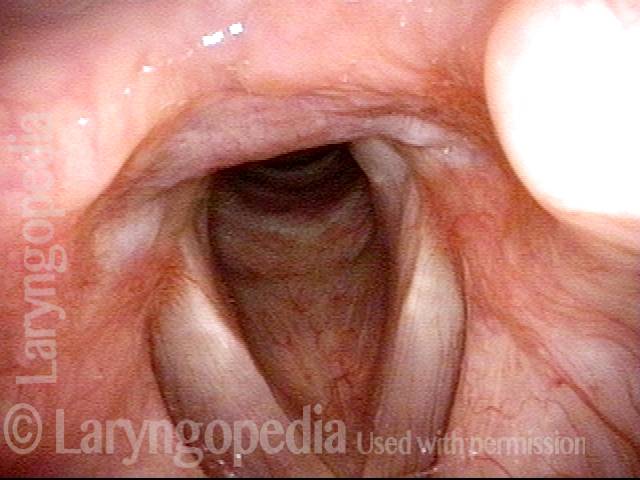

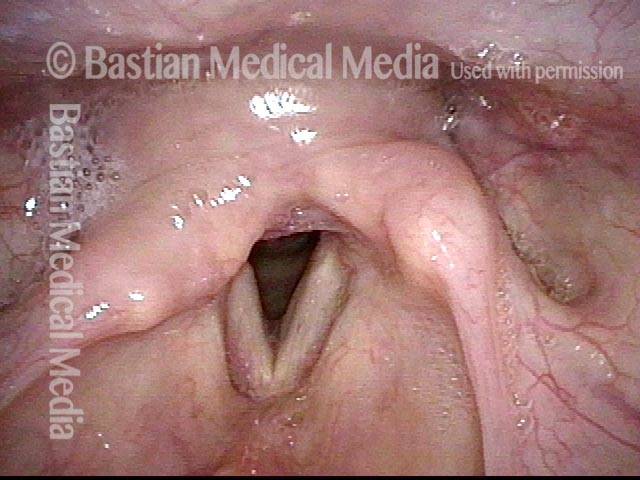

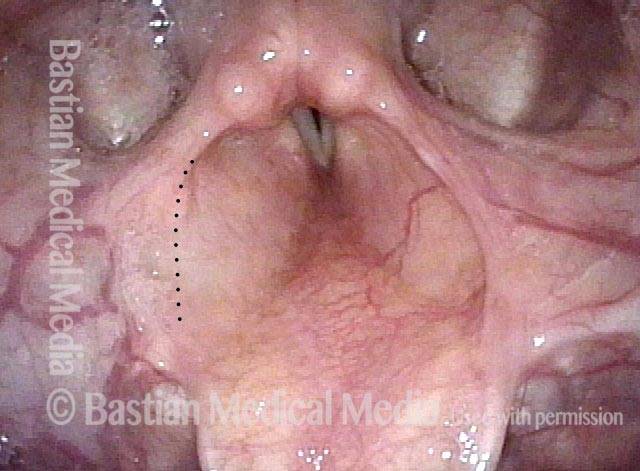

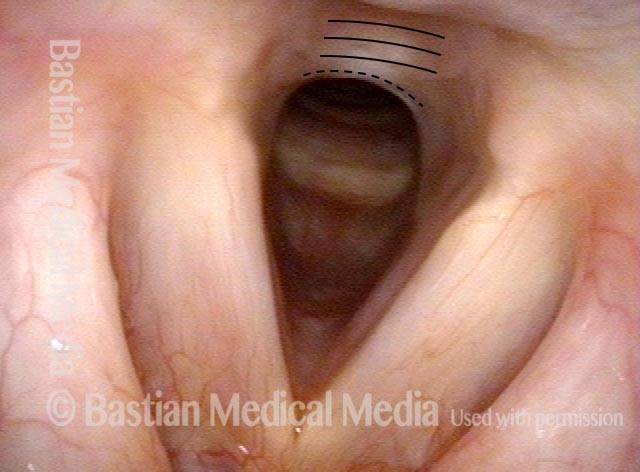

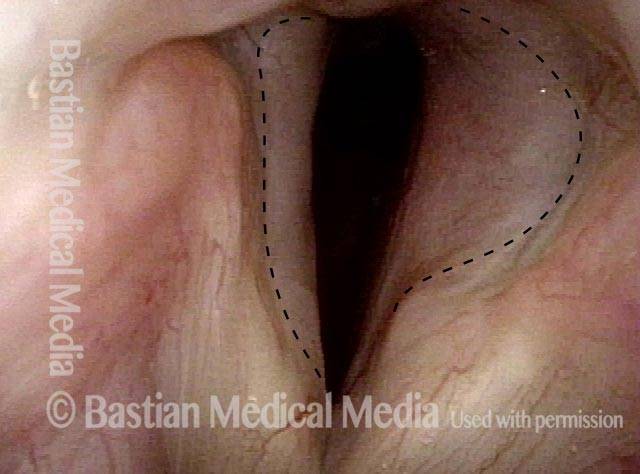

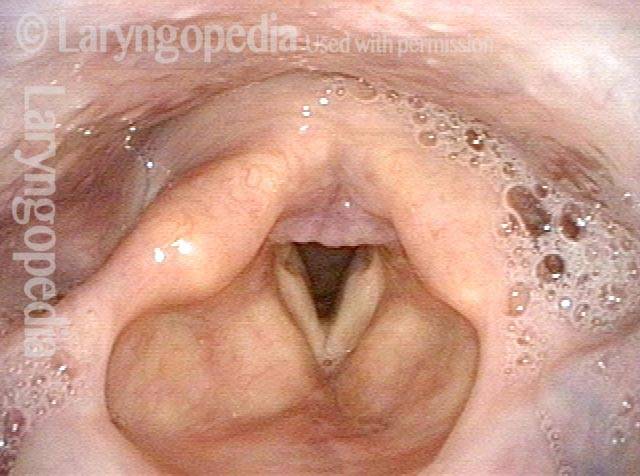

Vocal cord fixation (1 of 4)

Vocal cord fixation (1 of 4)

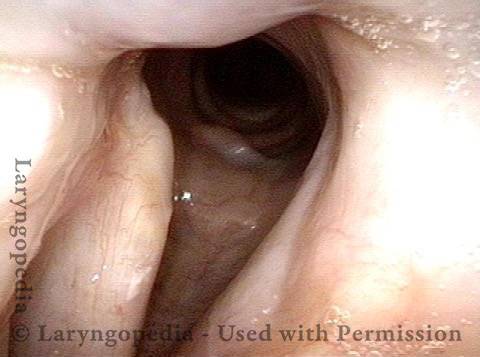

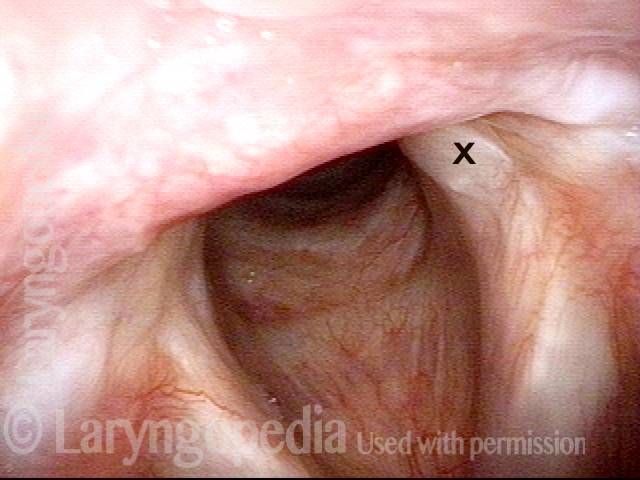

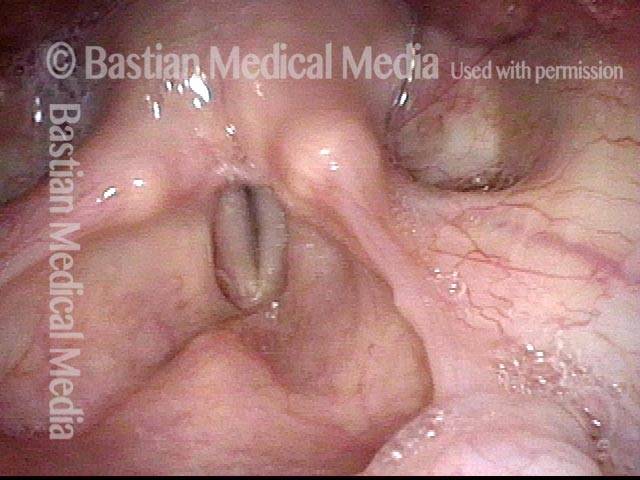

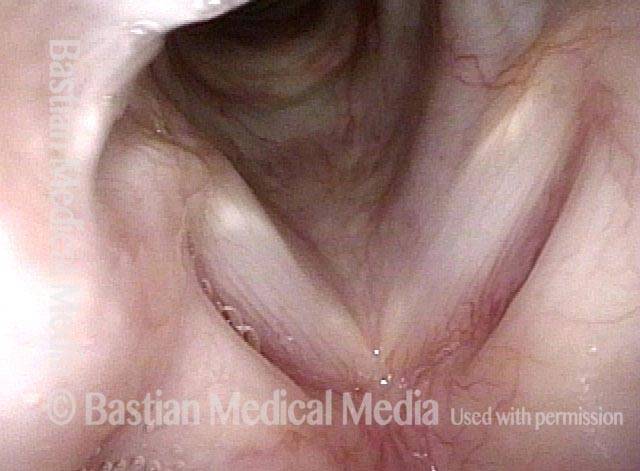

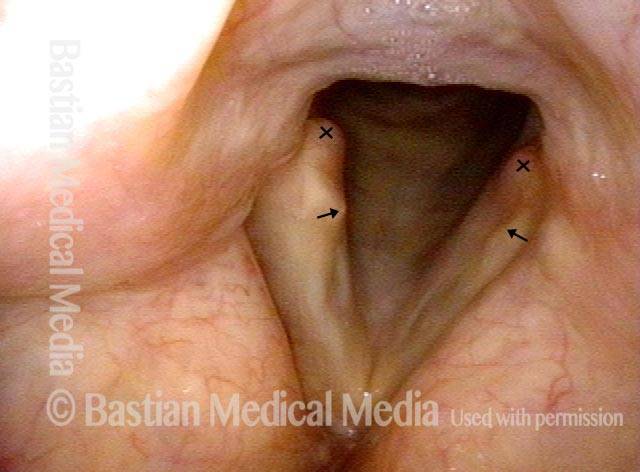

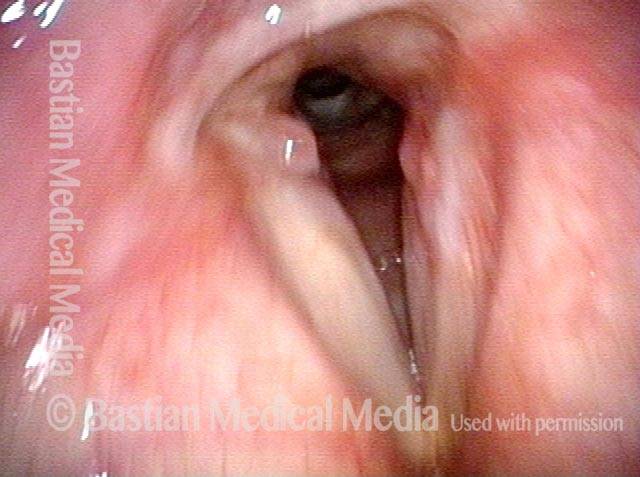

Paralysis (2 of 4)

Paralysis (2 of 4)

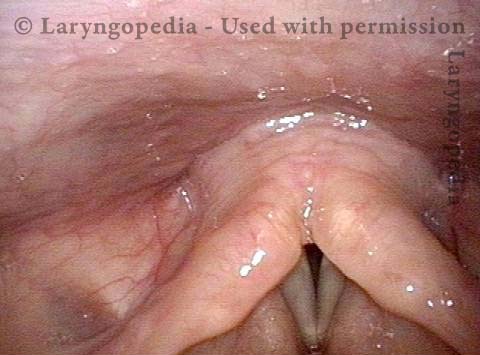

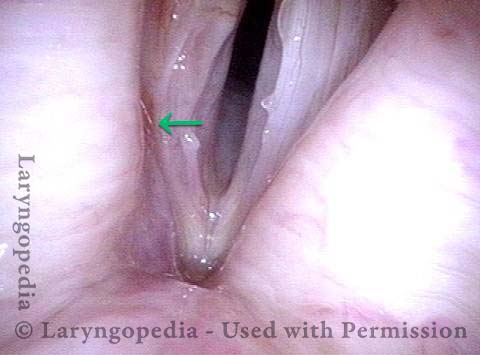

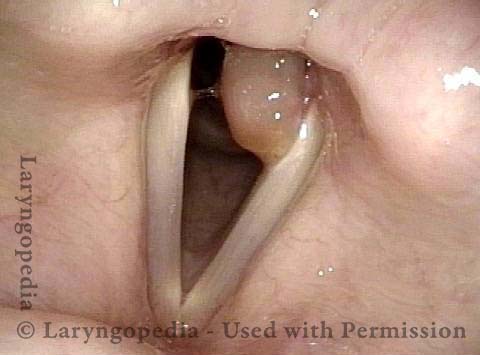

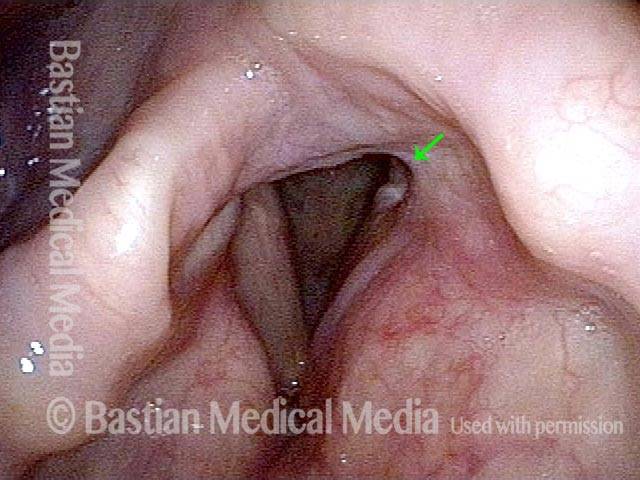

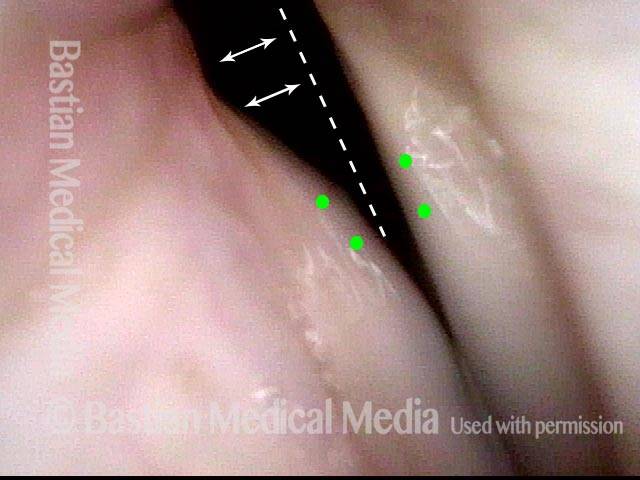

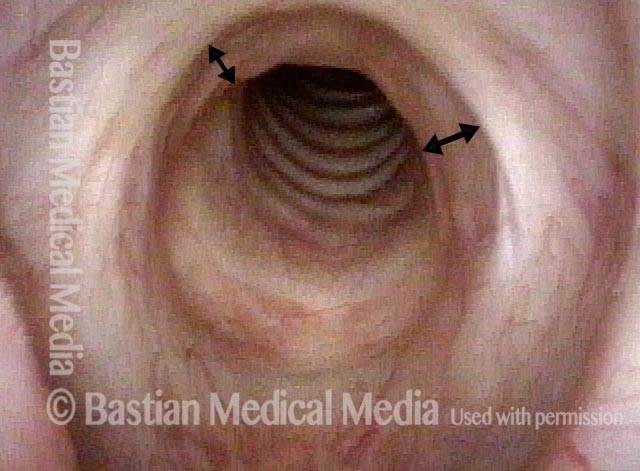

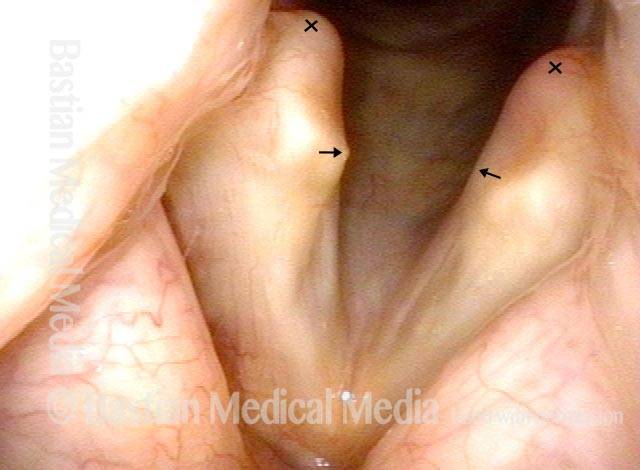

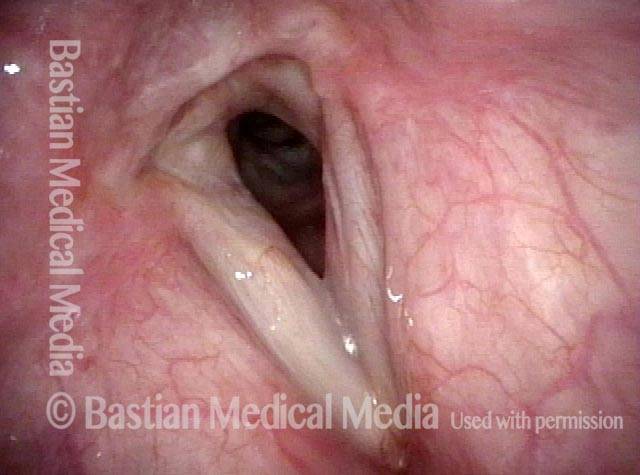

Injury from intubation tube (3 of 4)

Injury from intubation tube (3 of 4)

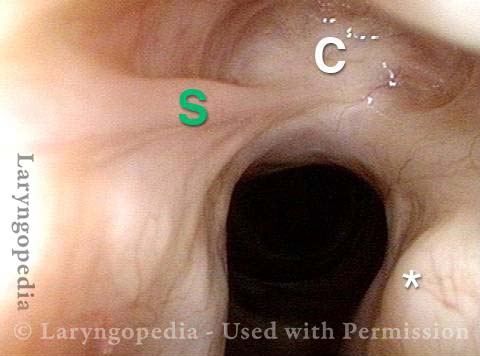

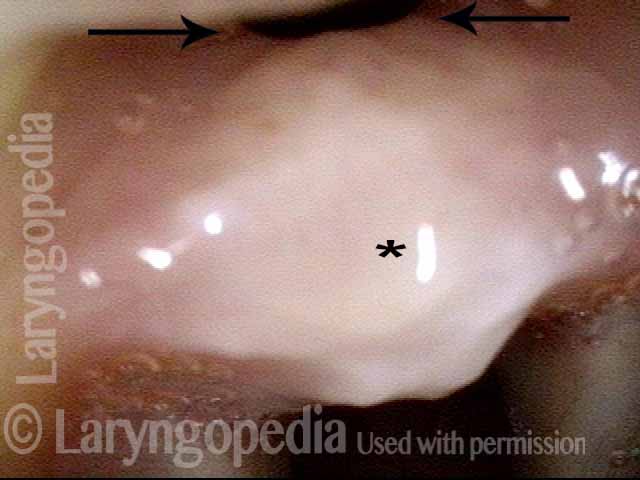

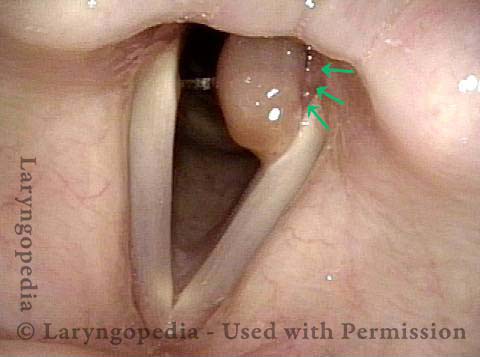

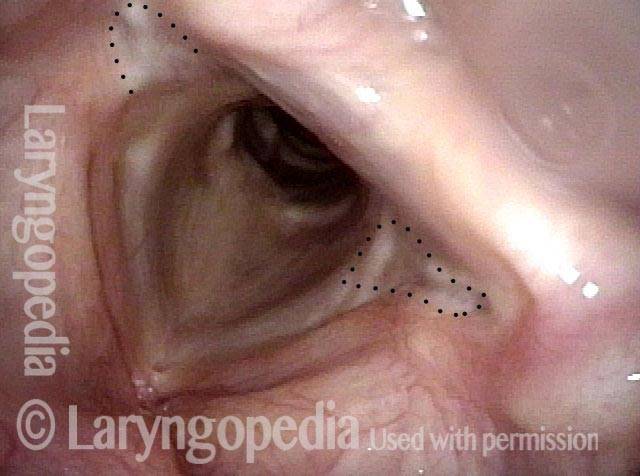

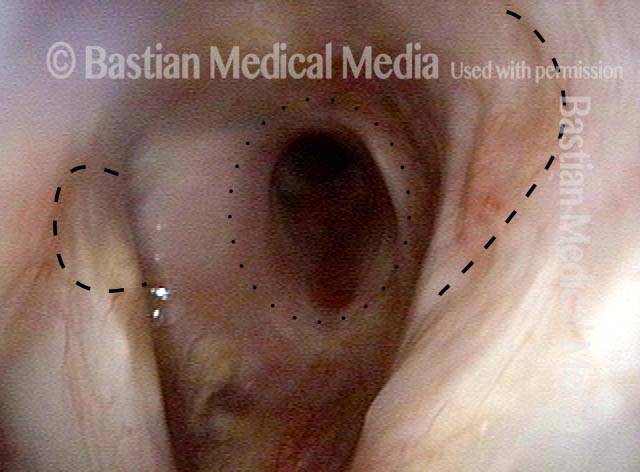

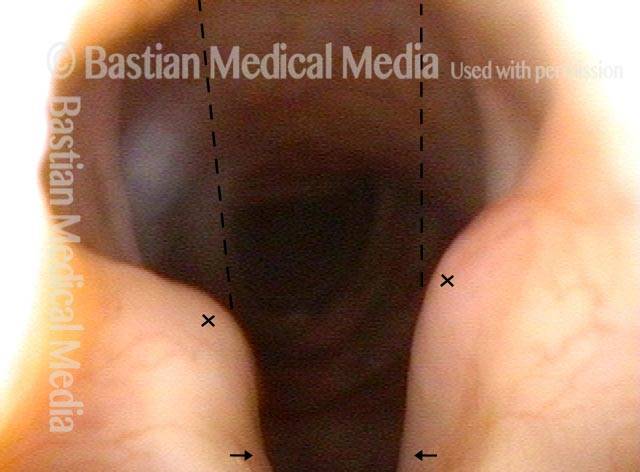

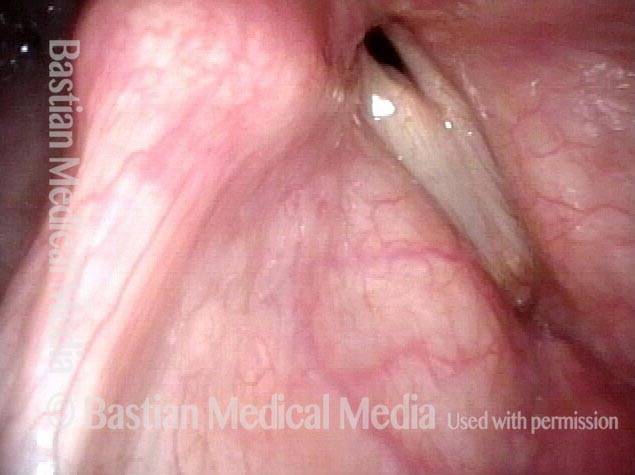

Mismatch of levels (4 of 4)

Mismatch of levels (4 of 4)

Breathing Tube Injury, not Vocal Cord Paralysis

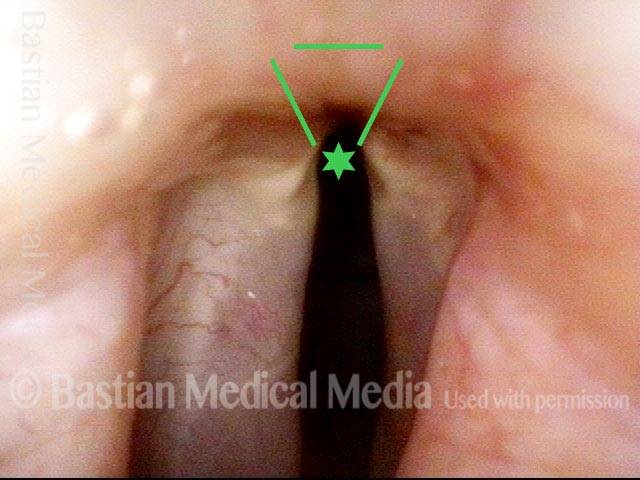

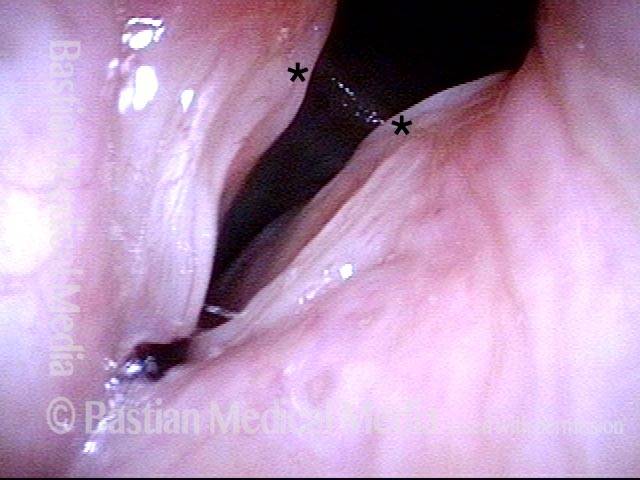

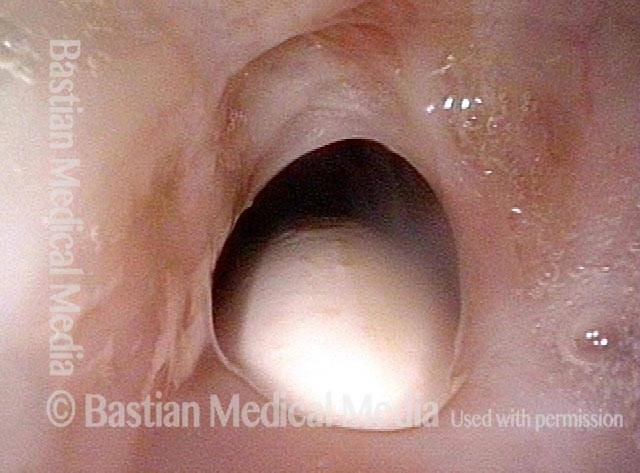

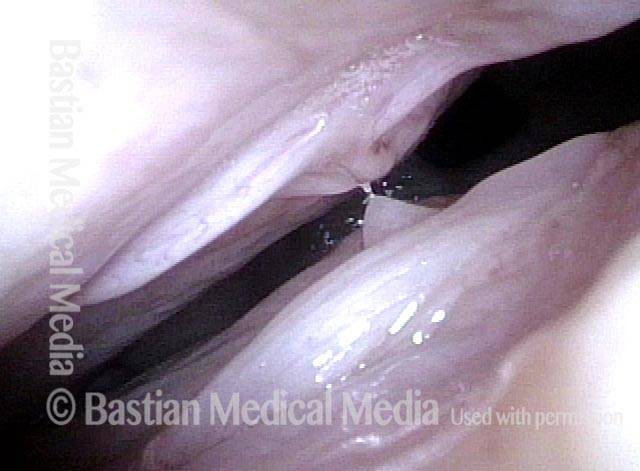

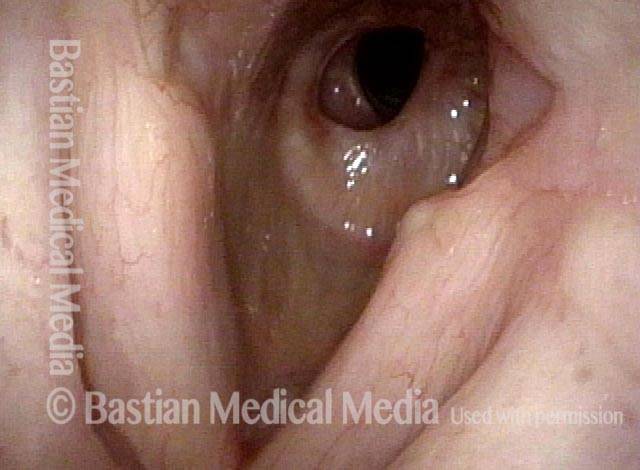

Aperture is very narrow (1 of 6)

Aperture is very narrow (1 of 6)

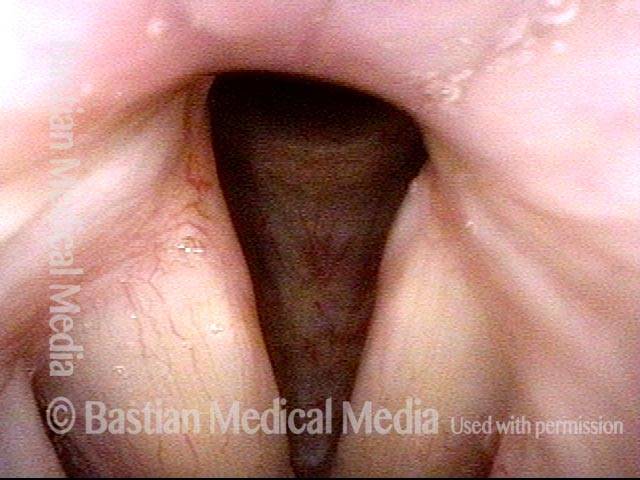

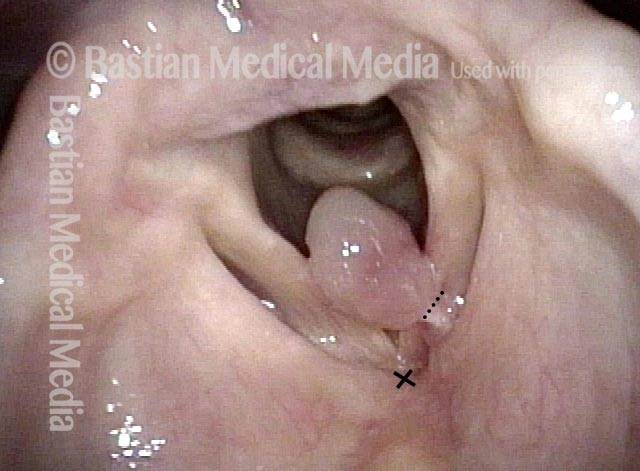

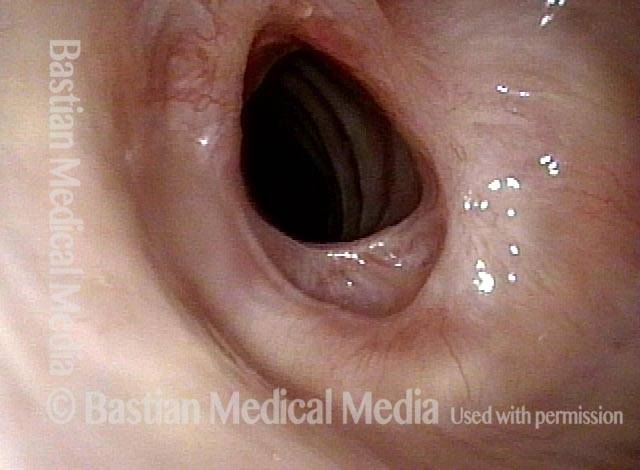

Involuntary inspiratory phonation (2 of 6)

Involuntary inspiratory phonation (2 of 6)

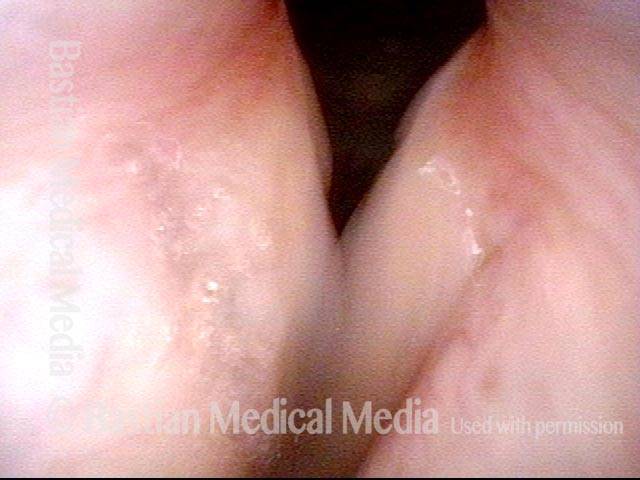

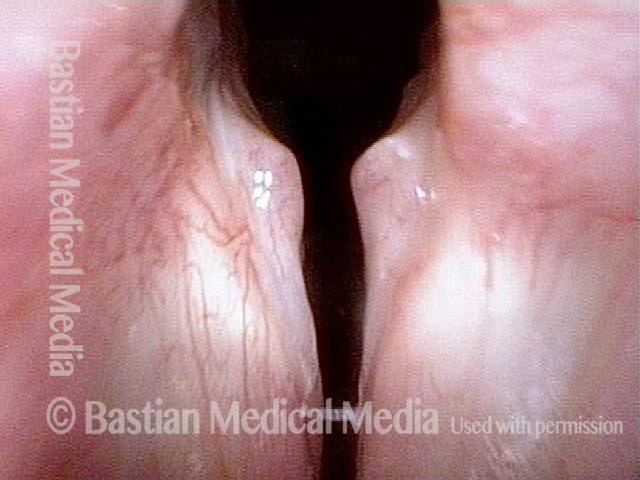

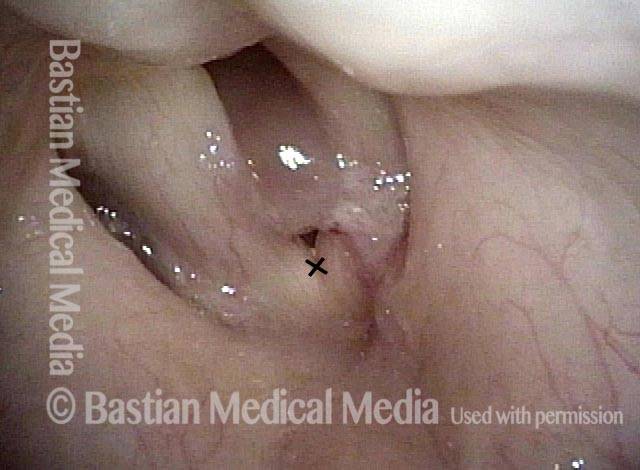

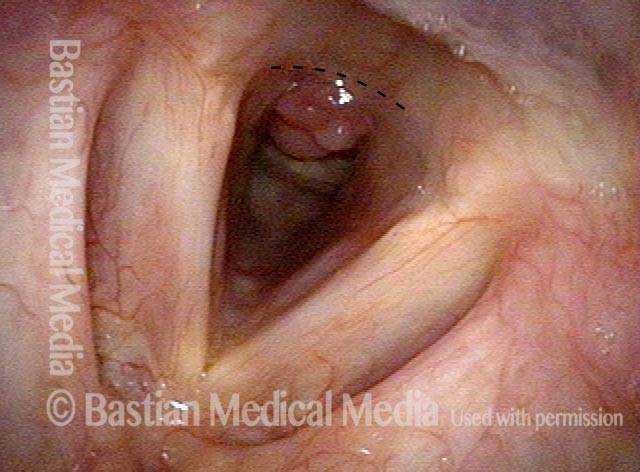

Divot on left vocal cord (3 of 6)

Divot on left vocal cord (3 of 6)

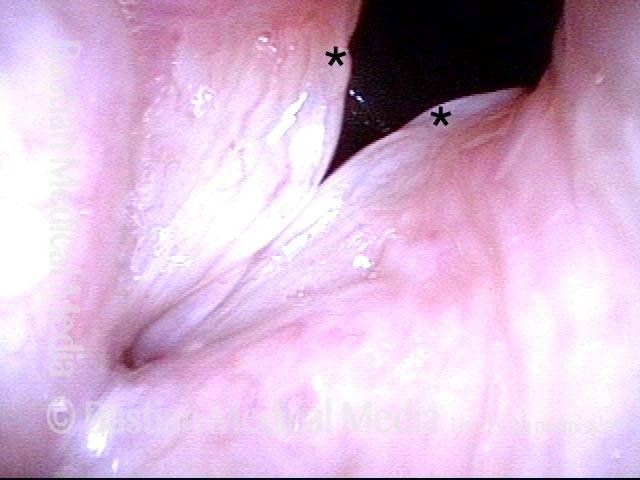

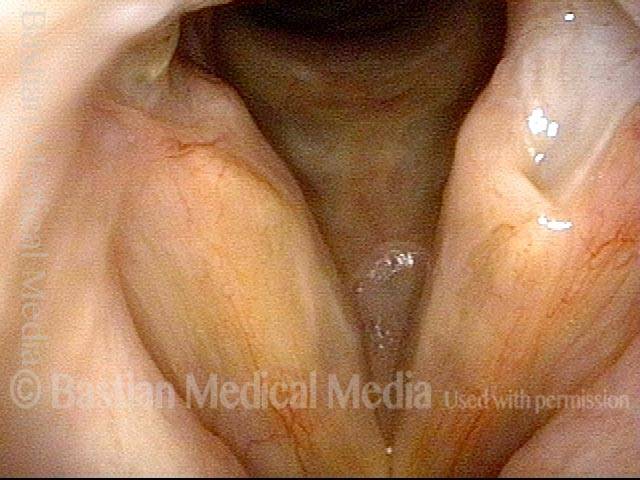

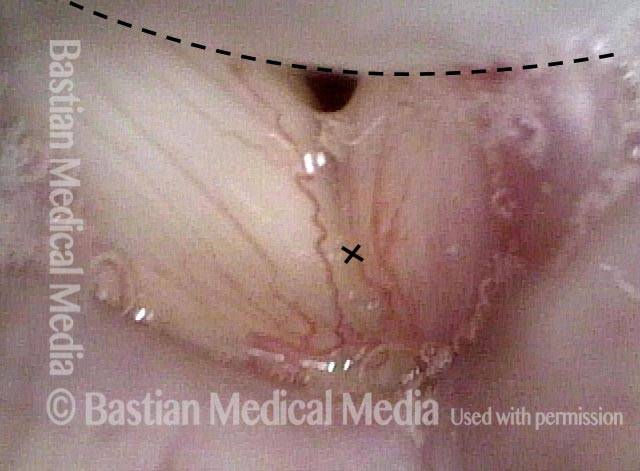

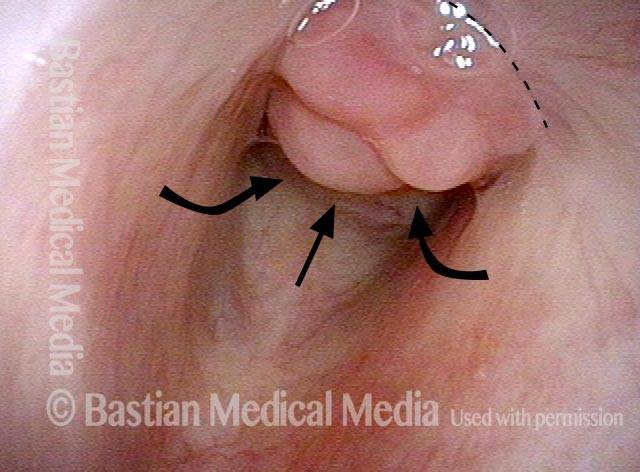

Endotracheal tube injury (4 of 6)

Endotracheal tube injury (4 of 6)

Laser cookie bite (5 of 6)

Laser cookie bite (5 of 6)

Surface scarring in the tracheotomy (6 of 6)

Surface scarring in the tracheotomy (6 of 6)

Breathing Tube Injury—A Rare Complication of Intubation for General Anesthesia

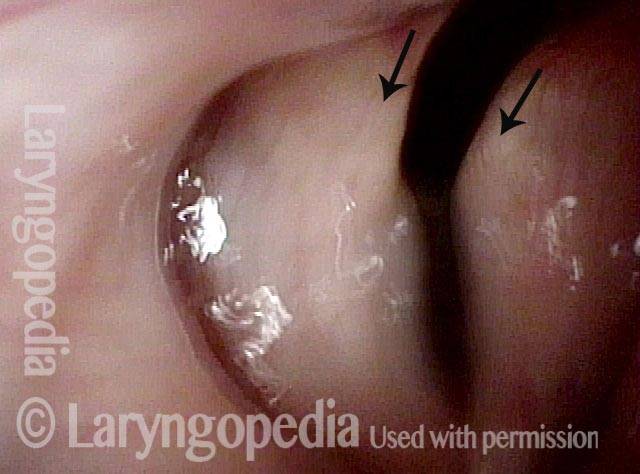

Inflamed vocal cord (1 of 5)

Inflamed vocal cord (1 of 5)

Closer view (2 of 5)

Closer view (2 of 5)

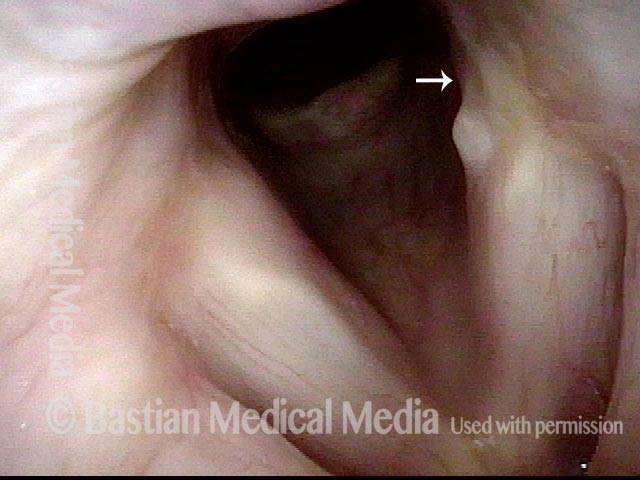

Scarring from intubation tube (3 of 5)

Scarring from intubation tube (3 of 5)

Mucosal Injury (4 of 5)

Mucosal Injury (4 of 5)

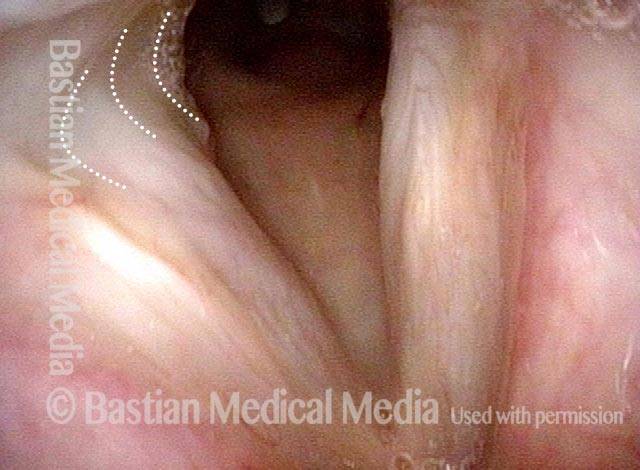

Flaccidity of right vocal cord (5 of 5)

Flaccidity of right vocal cord (5 of 5)

Conclusion: While we try to explain abnormality due to one cause, here, the patient has a mucosal injury and paresis of right TA and LCA muscles, which can also follow intubation. This explains why the initial postop voice was so weak and whispery, and also the rapid partial improvement. This voice will likely continue to improve and be very functional as a speaking voice. Fortunately, this person is not a singer, as clarity especially in upper notes, will likely be remain impaired even after full recovery.

Breathing Tube Injury: Synechiae

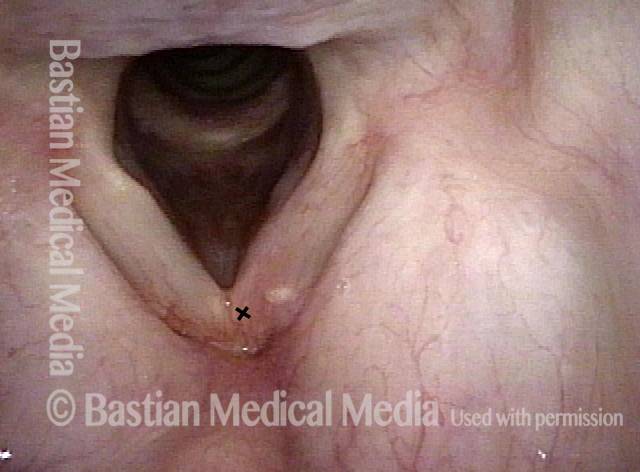

Breathing Tube Injury (1 of 4)

Breathing Tube Injury (1 of 4)

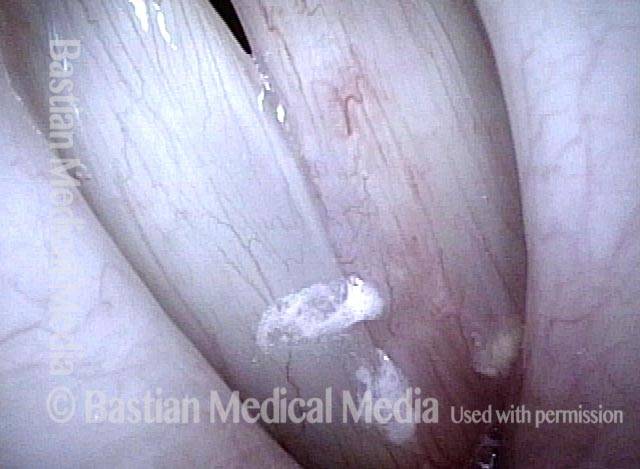

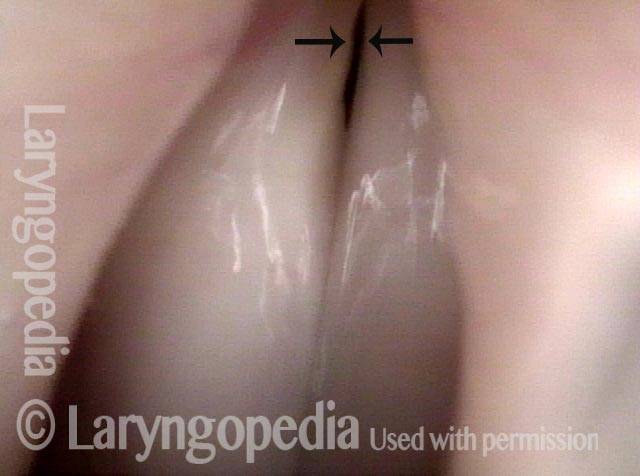

Post-intubation synechiae (2 of 4)

Post-intubation synechiae (2 of 4)

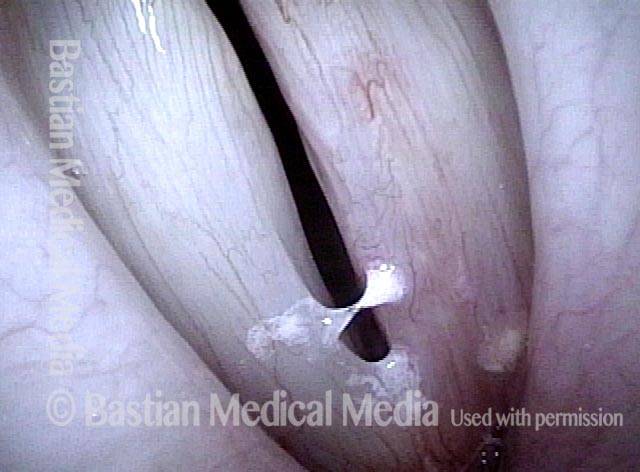

Breathing Tube Injury (3 of 4)

Breathing Tube Injury (3 of 4)

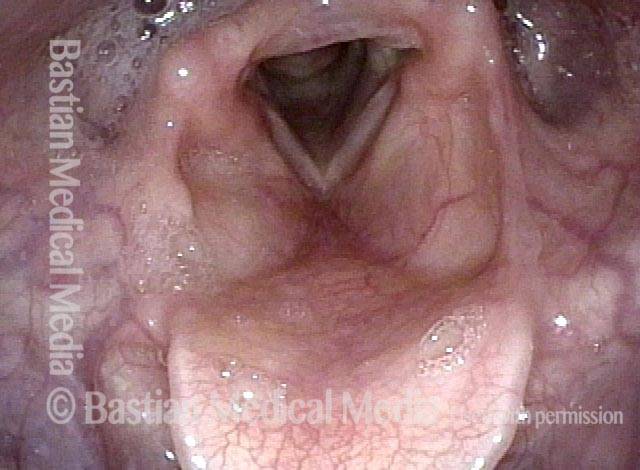

Breathing Tube Injury (4 of 4)

Breathing Tube Injury (4 of 4)

“Tattoo” of blood after detachment of intubation granuloma

Intubation granuloma (1 of 5)

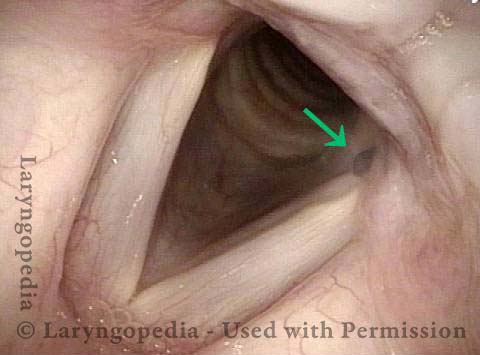

Intubation granuloma (1 of 5)

Intubation granuloma (2 of 5)

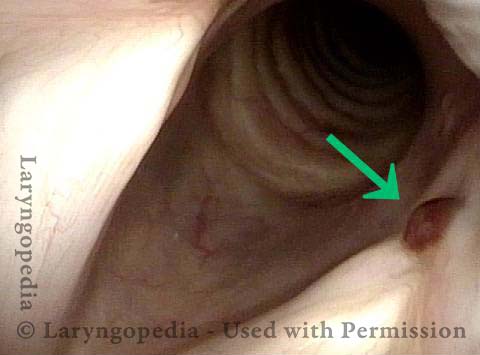

Intubation granuloma (2 of 5)

Granuloma is gone (3 of 5)

Granuloma is gone (3 of 5)

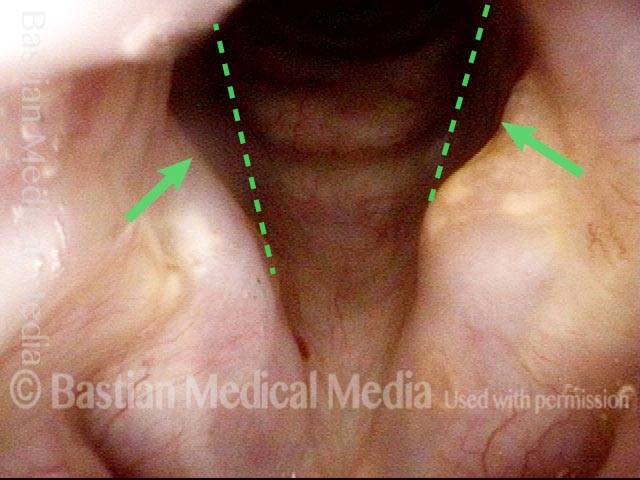

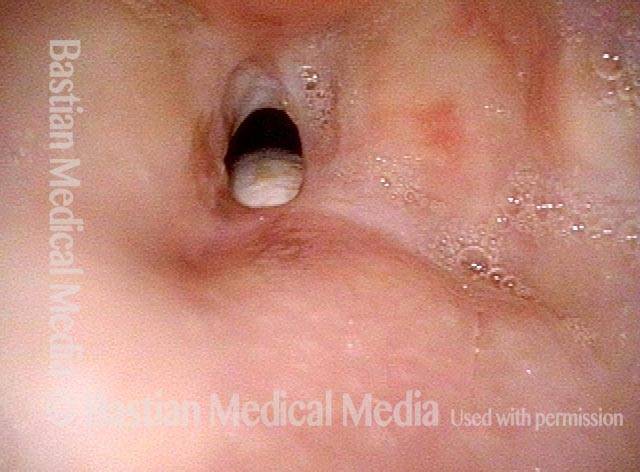

Blood tattoo (4 of 5)

Blood tattoo (4 of 5)

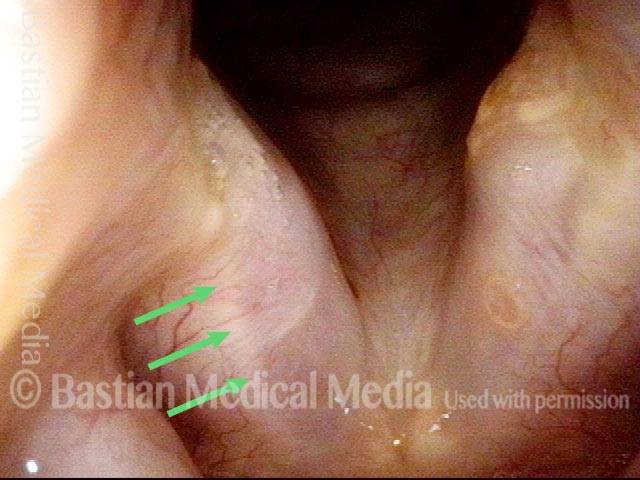

Blood Tattoo (5 of 5)

Blood Tattoo (5 of 5)

Intubation injury audio with photos:

Voice sample of a patient with a cricoartyenoid joint intubation injury (see this patient’s photos just below):

Intubation injury (1 of 3)

Intubation injury (1 of 3)

Intubation injury (2 of 3)

Intubation injury (2 of 3)

Maximum phonatory closure (3 of 3)

Maximum phonatory closure (3 of 3)

Intubation Injury Causing Partially Frozen Cricoarytenoid Joints

Intubation injury (1 of 4)

Intubation injury (1 of 4)

Intubation injury (2 of 4)

Intubation injury (2 of 4)

Closed phase of vibration (3 of 4)

Closed phase of vibration (3 of 4)

Open phase of vibration (4 of 4)

Open phase of vibration (4 of 4)

Intubation Injury

Abducted, breathing position (1 of 2)

Abducted, breathing position (1 of 2)

Intubation injury (2 of 2)

Intubation injury (2 of 2)

Example 2

Intubation injury (1 of 3)

Intubation injury (1 of 3)

Posterior commissure divots (2 of 3)

Posterior commissure divots (2 of 3)

Intubation injury (3 of 3)

Intubation injury (3 of 3)

Example 3

Intubation injury (1 of 4)

Intubation injury (1 of 4)

Breathy Voice (2 of 4)

Breathy Voice (2 of 4)

Vocal cord fixation (3 of 4)

Vocal cord fixation (3 of 4)

During phonation (4 of 4)

During phonation (4 of 4)

Forcing the Larynx to Give Up Its (Paresis and Intubation Injury) Secrets

Intubation injury (1 of 4)

Intubation injury (1 of 4)

Forceful exhalation (2 of 4)

Forceful exhalation (2 of 4)

Phonation begins (3 of 4)

Phonation begins (3 of 4)

LCA (4 of 4)

LCA (4 of 4)

Intubation Injury, Including A Subglottic Synechia

Intubation injury, including a subglottic synechia (1 of 2)

Intubation injury, including a subglottic synechia (1 of 2)

Intubation injury, including a subglottic synechia (2 of 2)

Intubation injury, including a subglottic synechia (2 of 2)

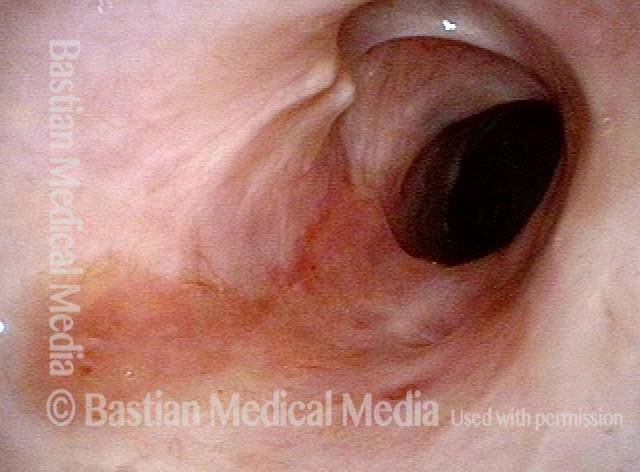

Post-Intubation Stenosis

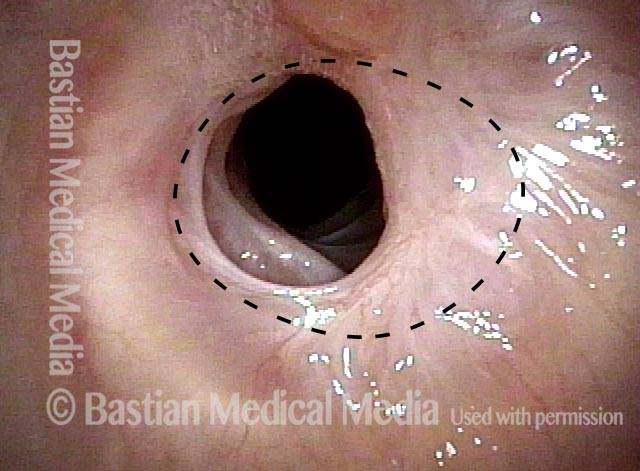

Endotrachel tube injury (1 of 4)

Endotrachel tube injury (1 of 4)

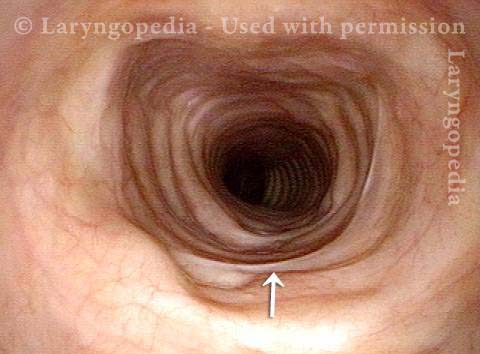

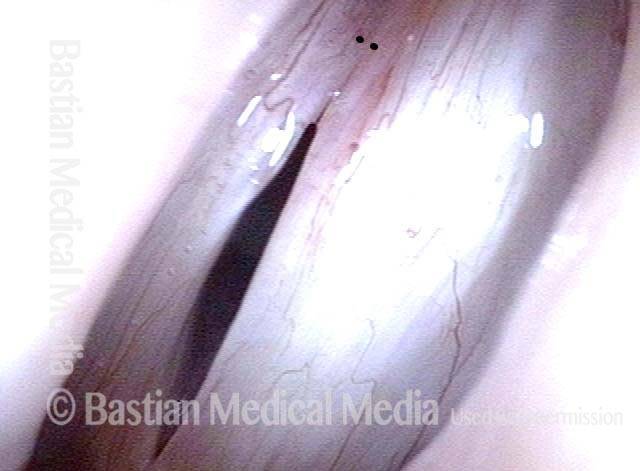

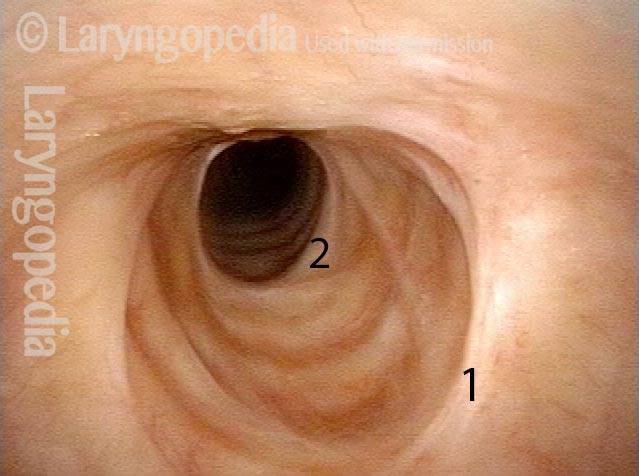

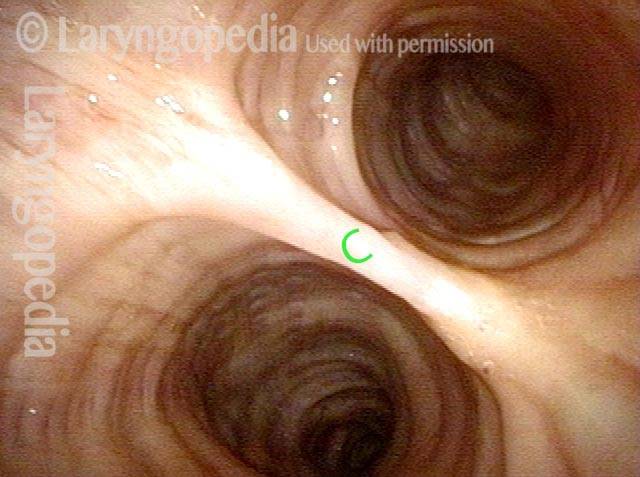

Closer view, between the posterior vocal cords (2 of 4)

Closer view, between the posterior vocal cords (2 of 4)

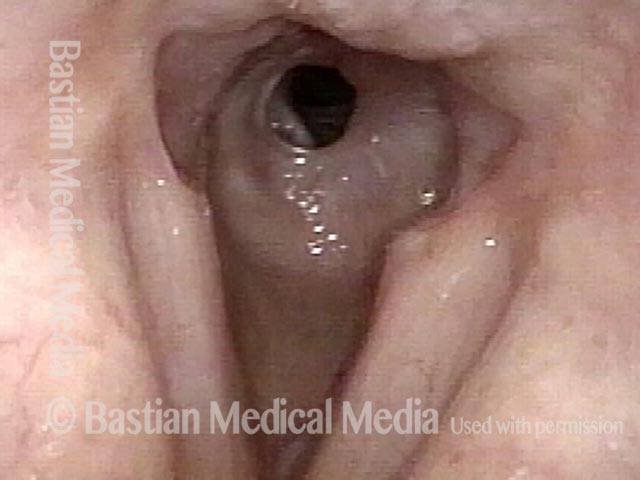

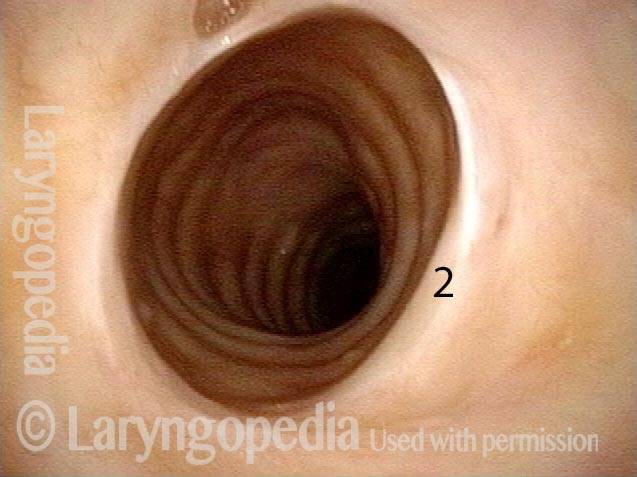

Even closer view, showing upper surface of the tube (3 of 4)

Even closer view, showing upper surface of the tube (3 of 4)

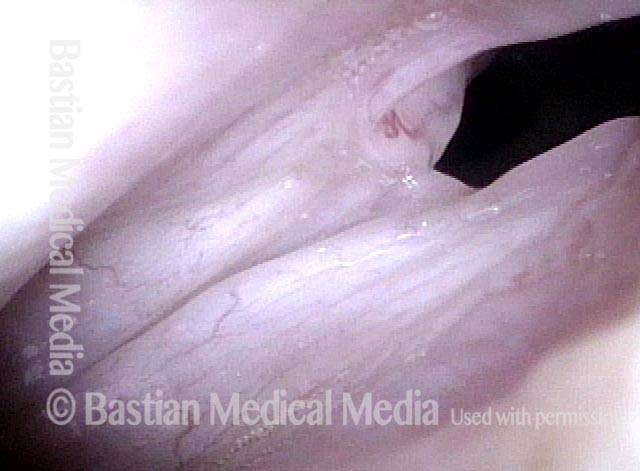

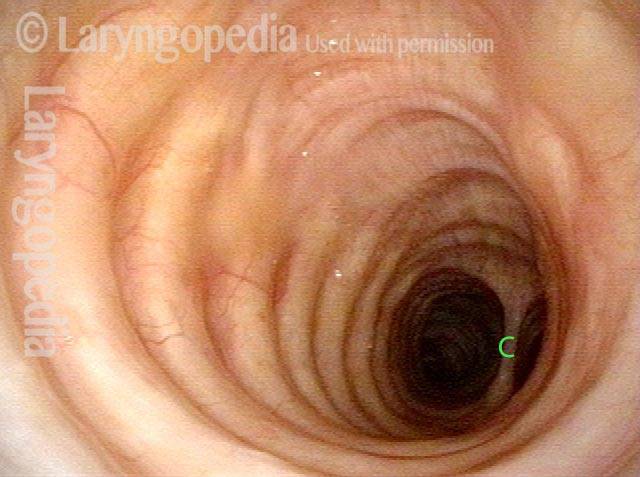

Non-inflammatory stenosis, caused purely by injury (4 of 4)

Non-inflammatory stenosis, caused purely by injury (4 of 4)

Vocal Cord “Tear” and Granuloma

Intubation injury (1 of 8)

Intubation injury (1 of 8)

Granuloma drawn into glottis (2 of 8)

Granuloma drawn into glottis (2 of 8)

Phonation (3 of 8)

Phonation (3 of 8)

Anterior commissure (4 of 8)

Anterior commissure (4 of 8)

Granuloma detached (5 of 8)

Granuloma detached (5 of 8)

Vocal cord blurring (6 of 8)

Vocal cord blurring (6 of 8)

Closed phase (7 of 8)

Closed phase (7 of 8)

Open phase (8 of 8)

Open phase (8 of 8)

Injured Adult Larynx from Intubation In Infancy

Intubation injury (1 of 6)

Intubation injury (1 of 6)

Phonation (2 of 6)

Phonation (2 of 6)

Breathing position (3 of 6)

Breathing position (3 of 6)

Prephonatory instant (4 of 6)

Prephonatory instant (4 of 6)

Phonatory blurring (5 of 6)

Phonatory blurring (5 of 6)

Scarring in subglottis (6 of 6)

Scarring in subglottis (6 of 6)

Intubation Injury to Voice, Airway, from Decades Ago

Severe intubation injury (1 of 5)

Severe intubation injury (1 of 5)

Subglottic stenosis (2 of 5)

Subglottic stenosis (2 of 5)

Mid-distal trachea (3 of 5)

Mid-distal trachea (3 of 5)

Posterior commissure keyhole (4 of 5)

Posterior commissure keyhole (4 of 5)

Flaccidity (5 of 5)

Flaccidity (5 of 5)

Injury at Two Levels from Breathing Tube-Particularly Clear

Posterior commissure divots (1 of 8)

Posterior commissure divots (1 of 8)

Closed phase (2 of 8)

Closed phase (2 of 8)

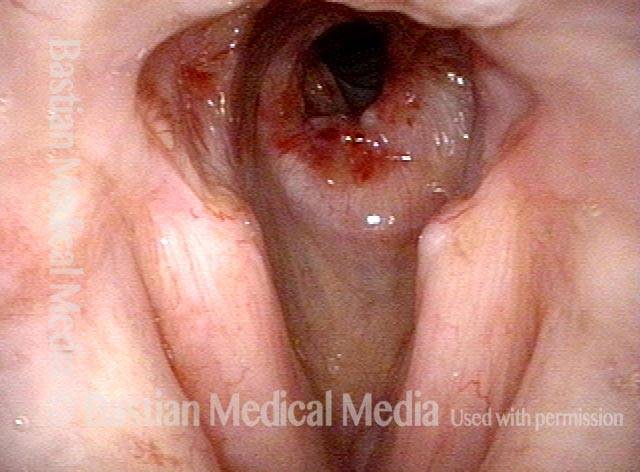

Subglottic stenosis (4 of 8)

Subglottic stenosis (4 of 8)

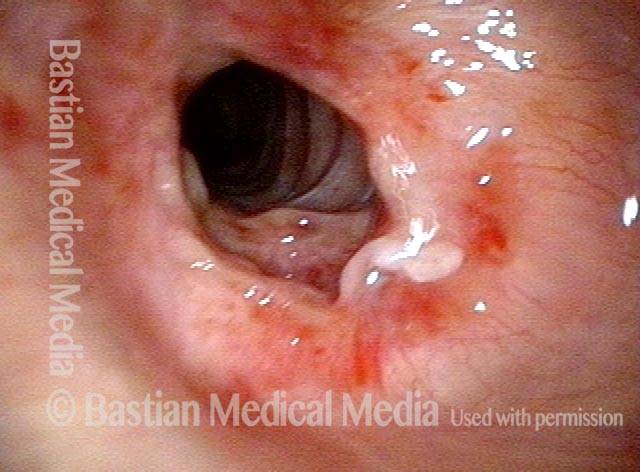

Post dilation (5 of 8)

Post dilation (5 of 8)

Closer view (6 of 8)

Closer view (6 of 8)

Final result (7 of 8)

Final result (7 of 8)

Closer view (8 of 8)

Closer view (8 of 8)

Subglottic Granulation and Curving Airstream

Intubation injury (1 of 4)

Intubation injury (1 of 4)

Lobules (2 of 4)

Lobules (2 of 4)

2 months later (3 of 4)

2 months later (3 of 4)

Scar band (4 of 4)

Scar band (4 of 4)

Double Whammy: Intubation Injury + Glottic Furrows

Intubation injury + glottic furrows (1 of 4)

Intubation injury + glottic furrows (1 of 4)

Bilateral glottic furrows (2 of 4)

Bilateral glottic furrows (2 of 4)

Intubation injury (3 of 4)

Intubation injury (3 of 4)

Phonatory position (4 of 4)

Phonatory position (4 of 4)

Sometimes You DO Remove Granulation to Avoid Tracheotomy

Granulation (1 of 8)

Granulation (1 of 8)

Closer view (2 of 8)

Closer view (2 of 8)

Post microlaryngoscopies (3 of 8)

Post microlaryngoscopies (3 of 8)

Scarring (4 of 8)

Scarring (4 of 8)

Post posterior commissuroplasty (5 of 8)

Post posterior commissuroplasty (5 of 8)

Breathing improved (6 of 8)

Breathing improved (6 of 8)

Closer view (7 of 8)

Closer view (7 of 8)

Phonatory view (8 of 8)

Phonatory view (8 of 8)

Who Knew…? Many Such Injuries Are Never Found

Coughing evaluation (1 of 6)

Coughing evaluation (1 of 6)

Intubation scars (2 of 6)

Intubation scars (2 of 6)

Stenosis (3 of 6)

Stenosis (3 of 6)

Further down trachea (4 of 6)

Further down trachea (4 of 6)

Below stenosis (5 of 6)

Below stenosis (5 of 6)

Carina (6 of 6)

Carina (6 of 6)

A Strapping Young Man Whose Larynx Was Injured As A 1-lb Preemie!

Intubated as preemie (1 of 4)

Intubated as preemie (1 of 4)

Left vocal cord (2 of 4)

Left vocal cord (2 of 4)

Vascular pattern (3 of 4)

Vascular pattern (3 of 4)

"Closed" phase (4 of 4)

"Closed" phase (4 of 4)

An “Inner Voice” Problem Viewed As An End-Organ Problem

Atrophied right vocal cord (1 of 4)

Atrophied right vocal cord (1 of 4)

Vocal cords at high volume (2 of 4)

Vocal cords at high volume (2 of 4)

Strobe light, closed phase (3 of 4)

Strobe light, closed phase (3 of 4)

Open phase (4 of 4)

Open phase (4 of 4)

Intubation Scar With Pseudo-Polyp

Posterior swelling (1 of 3)

Posterior swelling (1 of 3)

White scar (2 of 3)

White scar (2 of 3)

Pseudopolyp (3 of 3)

Pseudopolyp (3 of 3)

- Bastian RW, Richardson BE. Postintubation phonatory insufficiency: an elusive diagnosis. Otolaryngol Head and Neck Surg. 2001; 124(6): 625-33. [↩]