Vocal Cord Paresis

Vocal cord paresis is the partial loss of voluntary motion for one or more of the muscles that move the vocal cords. Paresis is to be distinguished from paralysis, which refers to a complete loss of motion. Sometimes, however, the terms “paralysis” or “paralyzed” are used less precisely to encompass any kind of loss of motion, partial or complete. But we prefer the term “paresis” whenever it applies, and below we suggest a way to use this term when describing more complicated cases of vocal cords with reduced or no mobility.

Paresis vs. Paralysis

Paresis or paralysis of a muscle or muscle group is caused by damage to its nerve supply. In other words, the underlying cause of a paretic or paralyzed muscle’s immobility is not a disorder of that muscle per se, but a disorder of the nerve supplying that muscle.

Perhaps for this reason, it is common to speak of paralysis according to the nerve involved, rather than the muscle or muscles; in the world of laryngology, for example, we speak of “paralysis of the recurrent nerve.” However, it seems more logical to describe paralysis or paresis according to what is actually immobilized: the muscles.

For example: if in a given case only the posterior cricoarytenoid (PCA) muscle is immobilized, then instead of calling that “paralysis of the recurrent nerve,” we would call it “PCA-only vocal cord paresis.”

In that example, though, some might wonder if it would be better for us to say “paralysis” instead of “paresis.” In other words, should we describe the nature of the immobility of the PCA muscle alone (so that, if the PCA is totally immobile, we would say “PCA-only vocal cord paralysis”) or that of the vocal cord’s entire set of muscles (which as a group is only partially immobile, so we would stick with “PCA-only vocal cord paresis”)? We think that, in general, it is more helpful to do the latter.

To illustrate, here is an imaginary conversation: “Is this vocal cord paralyzed or paretic?” “Paretic.” “Which kind of paresis is it?” “PCA-only.”

Types of Paresis

It is surprisingly easy to diagnose the different variants of vocal cord paresis with a straightforward visual examination. Click on a particular variant to learn more:

- Vocal cord paresis, TA + LCA

- Vocal cord paresis, TA-only

- Vocal cord paresis, LCA-only

- Vocal cord paresis, PCA-only

- Vocal cord paresis, IA-only

Vocal Cord Paresis (Thyroarytenoid Muscle) Accentuated by Disuse

This woman illustrates that vocal cords are inhabited by muscle (thyroarytenoid muscle, to be precise). If that muscle atrophies due to paresis (partial loss of nerve supply), this alone can weaken the voice. That is what happened to her 10 years ago, in her fifties, after thyroid surgery. Initially the left cord did not move (paralysis). Then movement returned and along with it, her voice gradually gained in strength.

When recovery was maximal, the vocal cord abducted (opened) and adducted (closed) normally. She also regained “90%” of her voice; while the muscle within the vocal cord did not recover fully, there was sufficient strength and tone to mostly “keep up” with the demands of her moderate voice use. Technically, she began with paralysis (of TA, LCA, and PCA) but after recovery, had a TA-only paresis as shown in photos 1-3 below. All was well for 10 years as she had a perfectly functional voice.

Ten years later, now in her sixties, she developed a bad URI (not Covid-19) and voice deteriorated in the midst of hard bouts of coughing. At the same time, due to retirement, and self-quarantine, she was using voice very little.

Two months later, still using voice very little and even intentionally “resting it,” her voice is extremely weak. The explanation is that by figuratively putting her voice in bed, she has added disuse atrophy to the longstanding paresis. How do we know this? The answer is in photos 4-5 below. And the appropriate initial treatment? Voice building exercises.

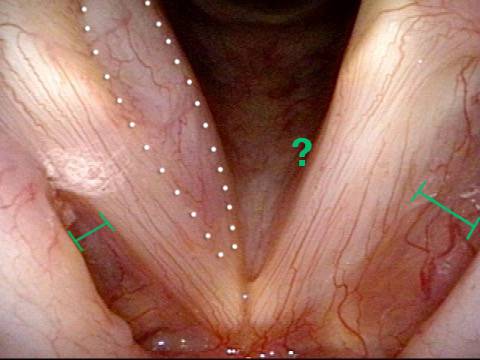

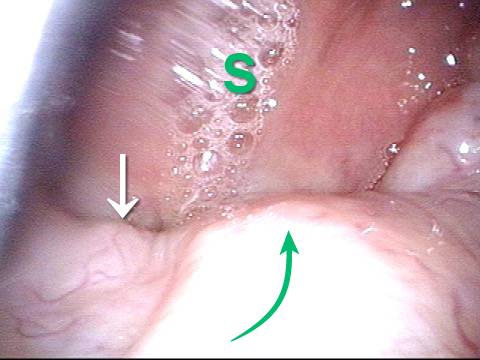

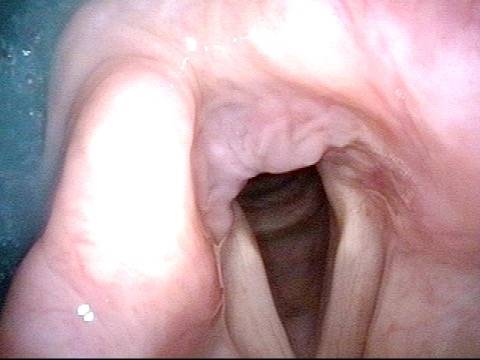

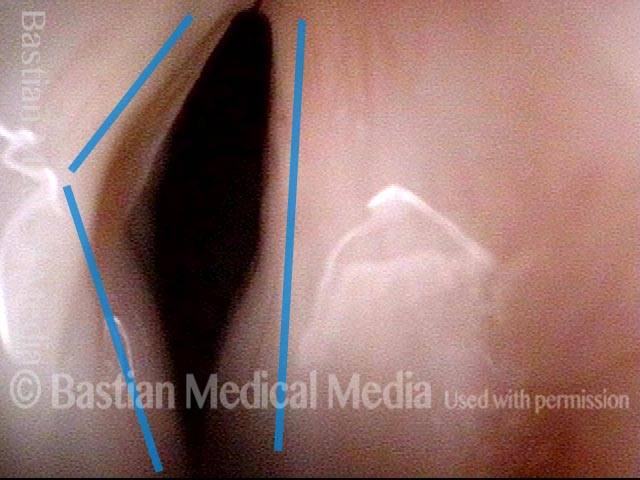

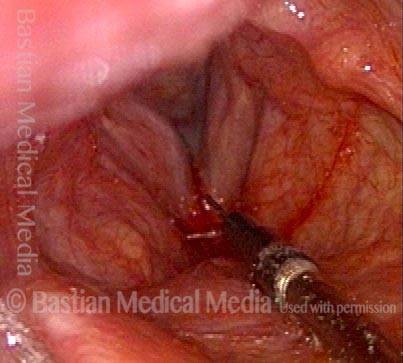

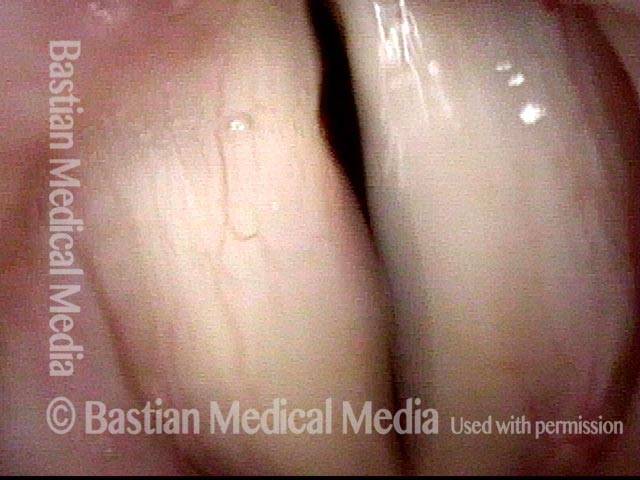

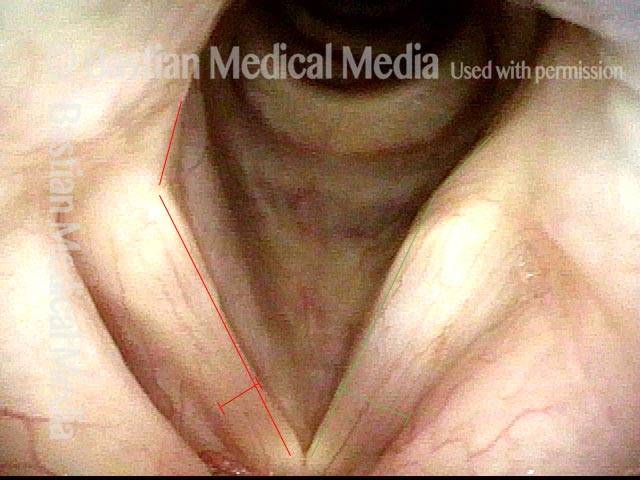

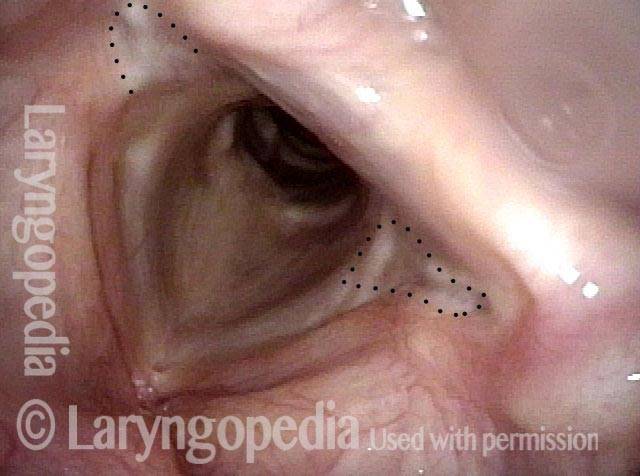

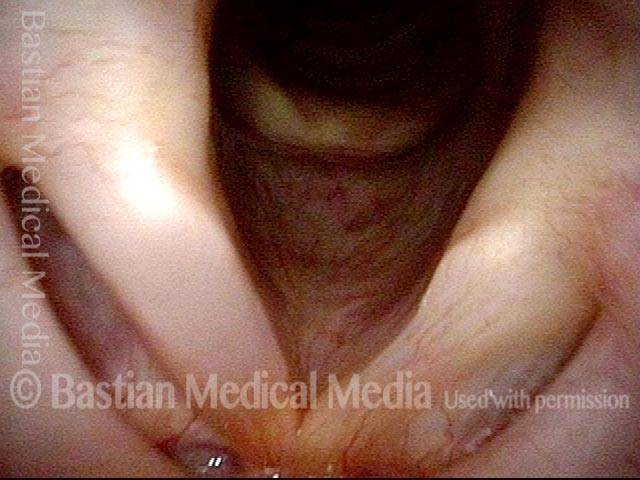

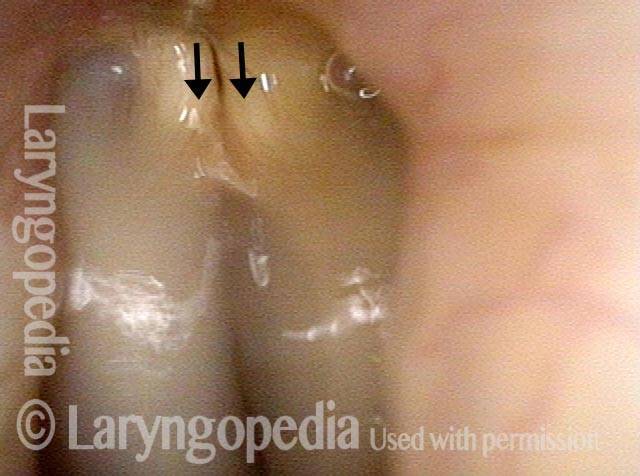

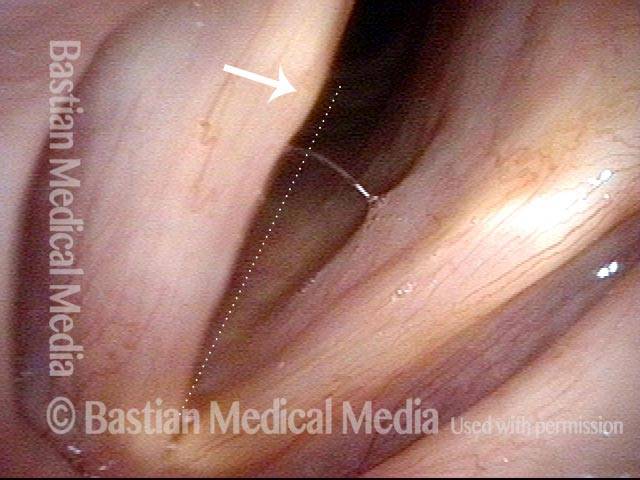

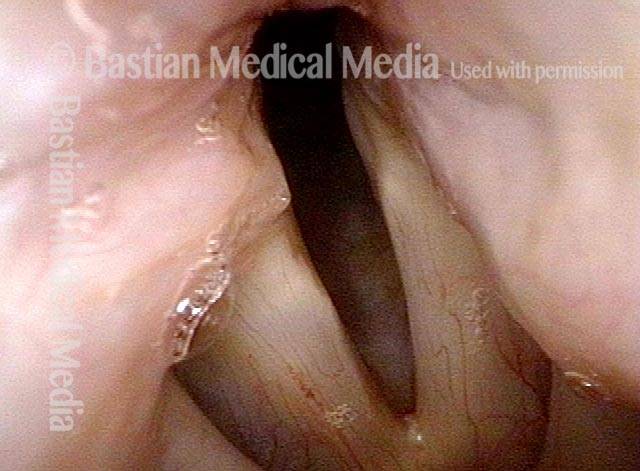

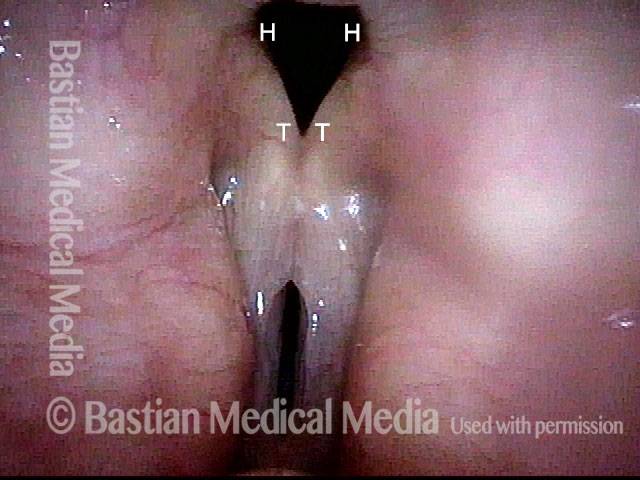

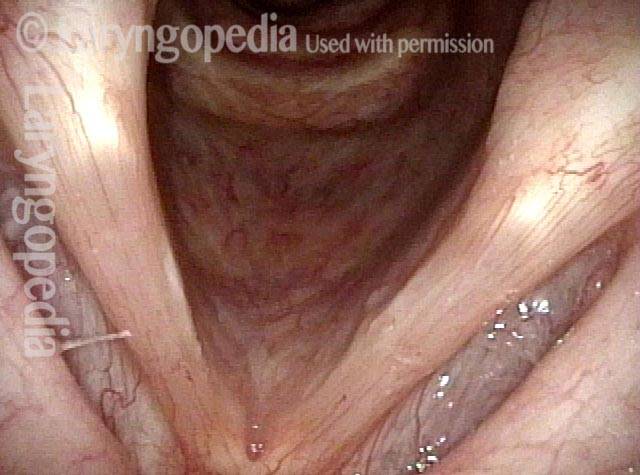

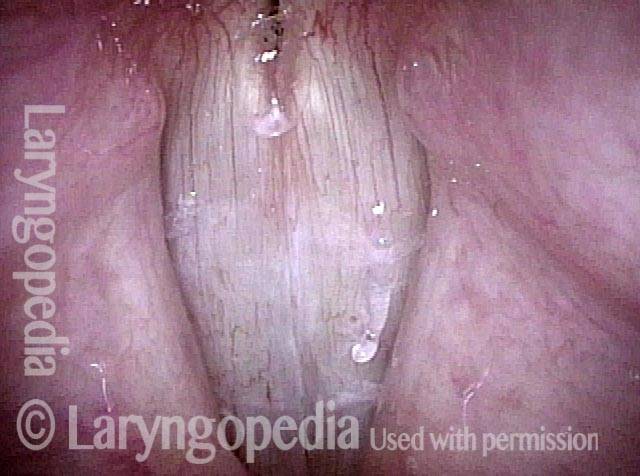

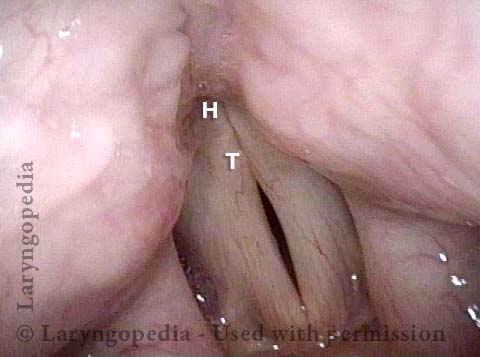

Conus bulge in the larynx (1 of 5)

Conus bulge in the larynx (1 of 5)

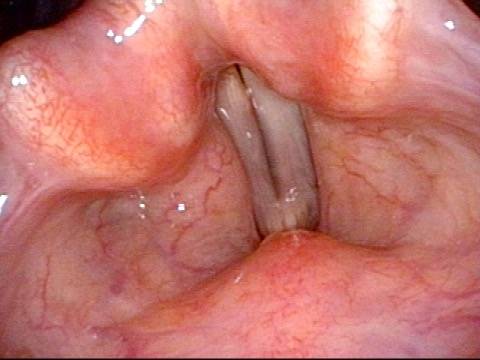

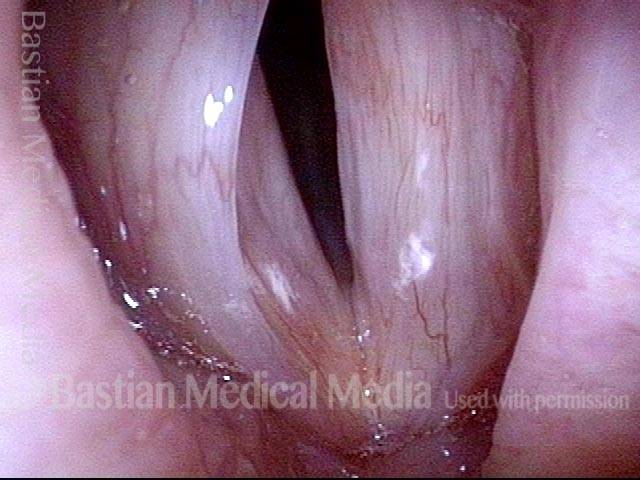

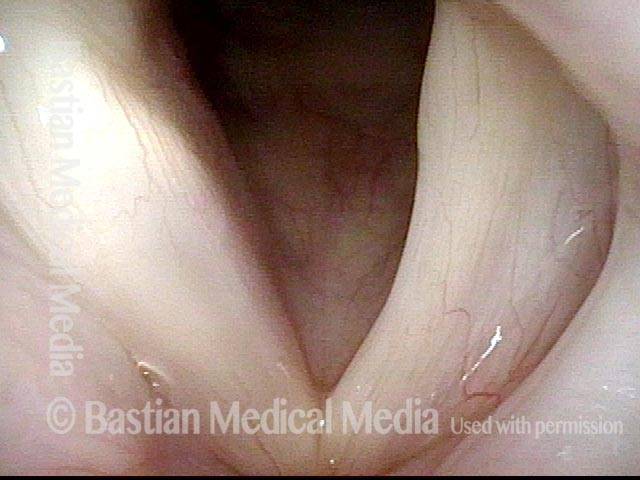

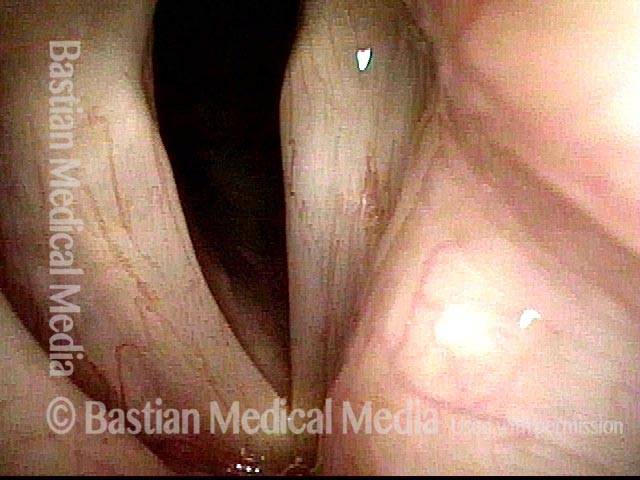

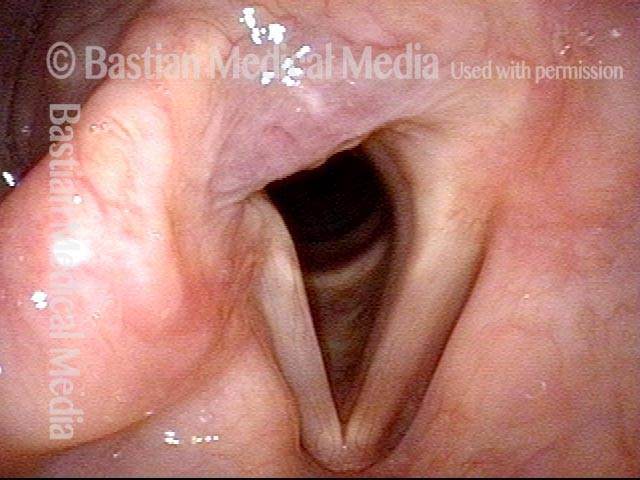

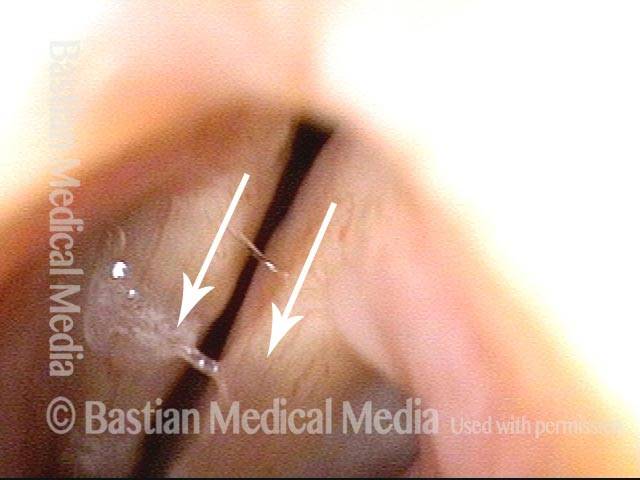

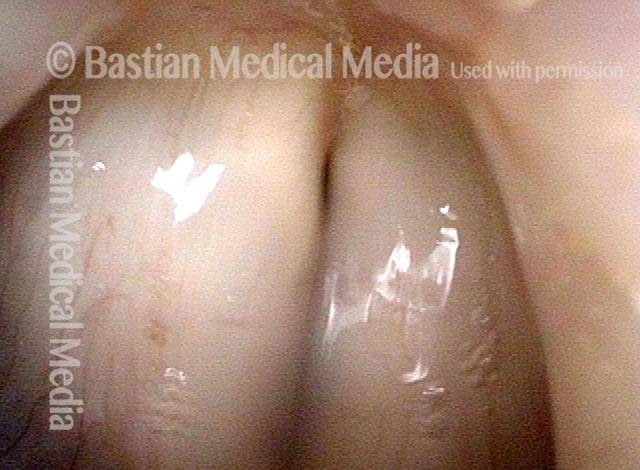

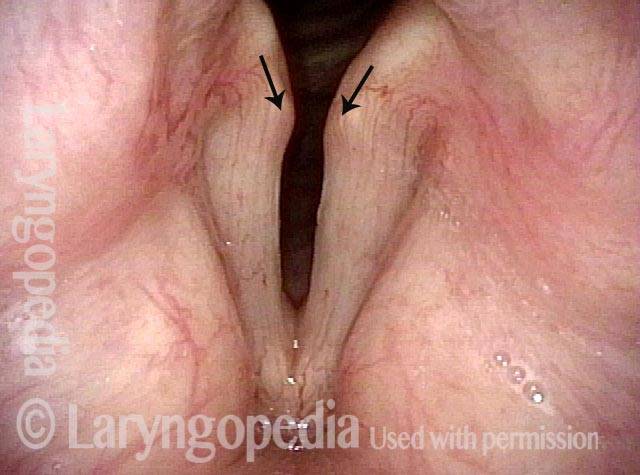

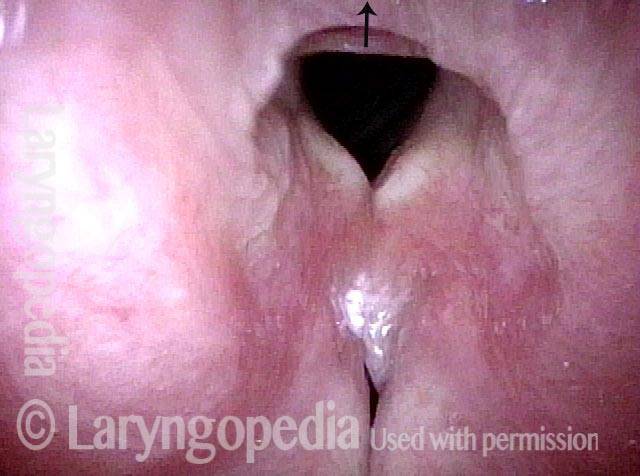

Left vocal cord adducts normally (2 of 5)

Left vocal cord adducts normally (2 of 5)

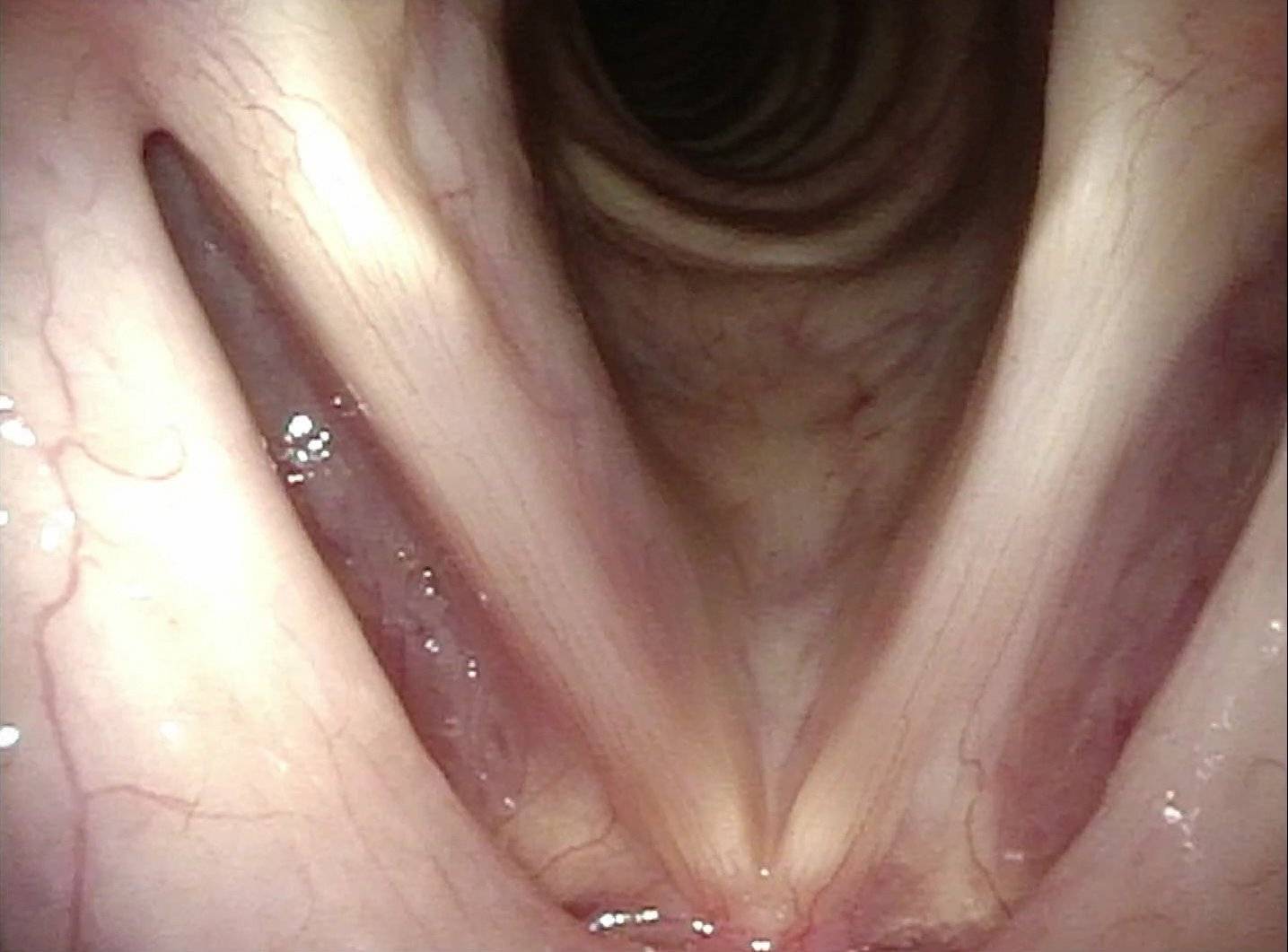

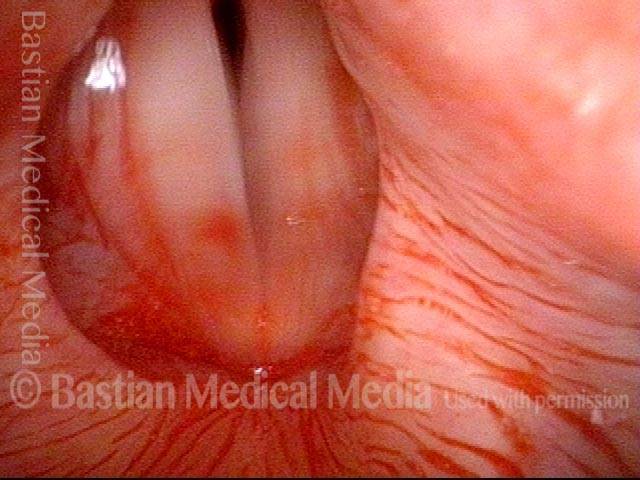

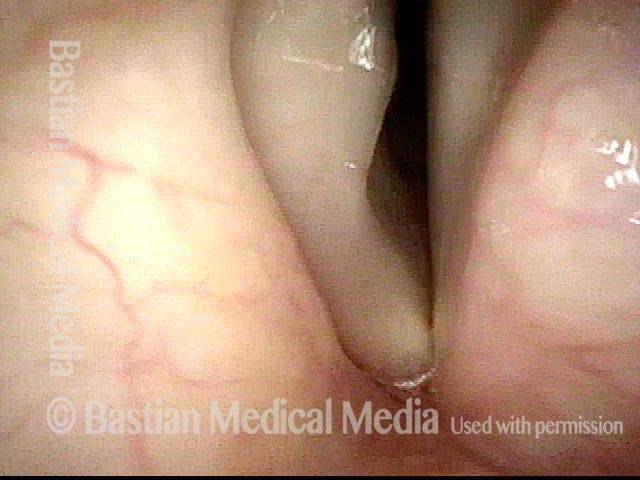

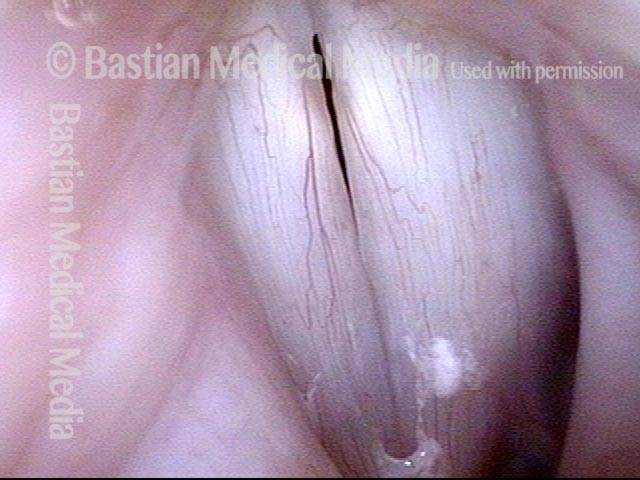

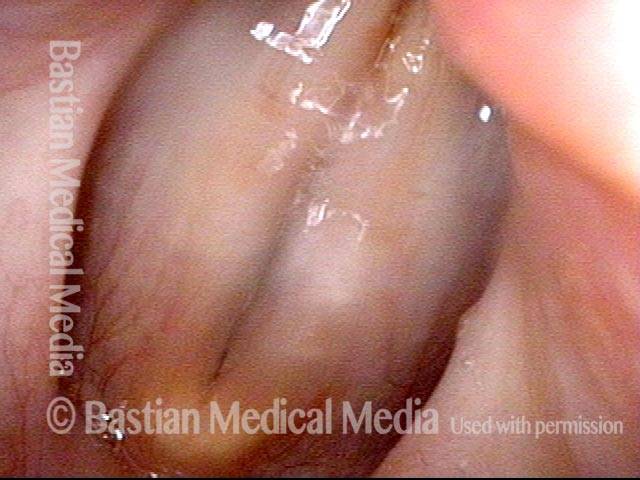

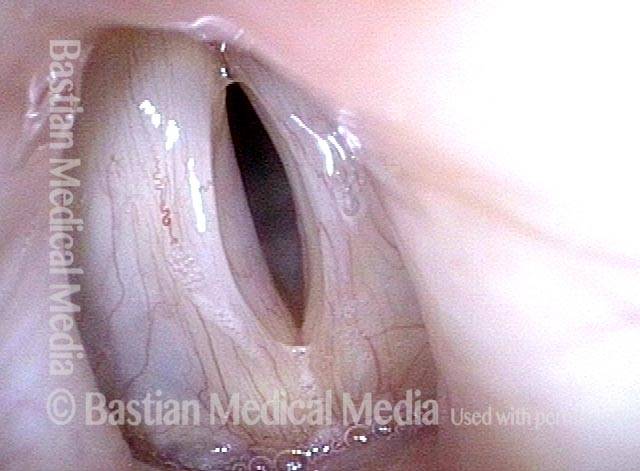

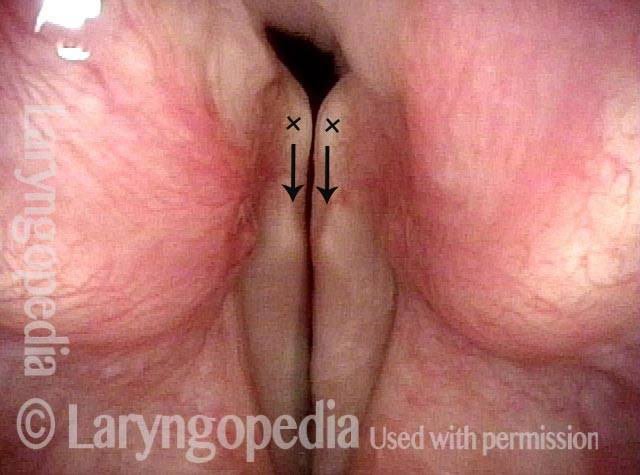

Voice remains strong despite atrophy (3 of 5)

Voice remains strong despite atrophy (3 of 5)

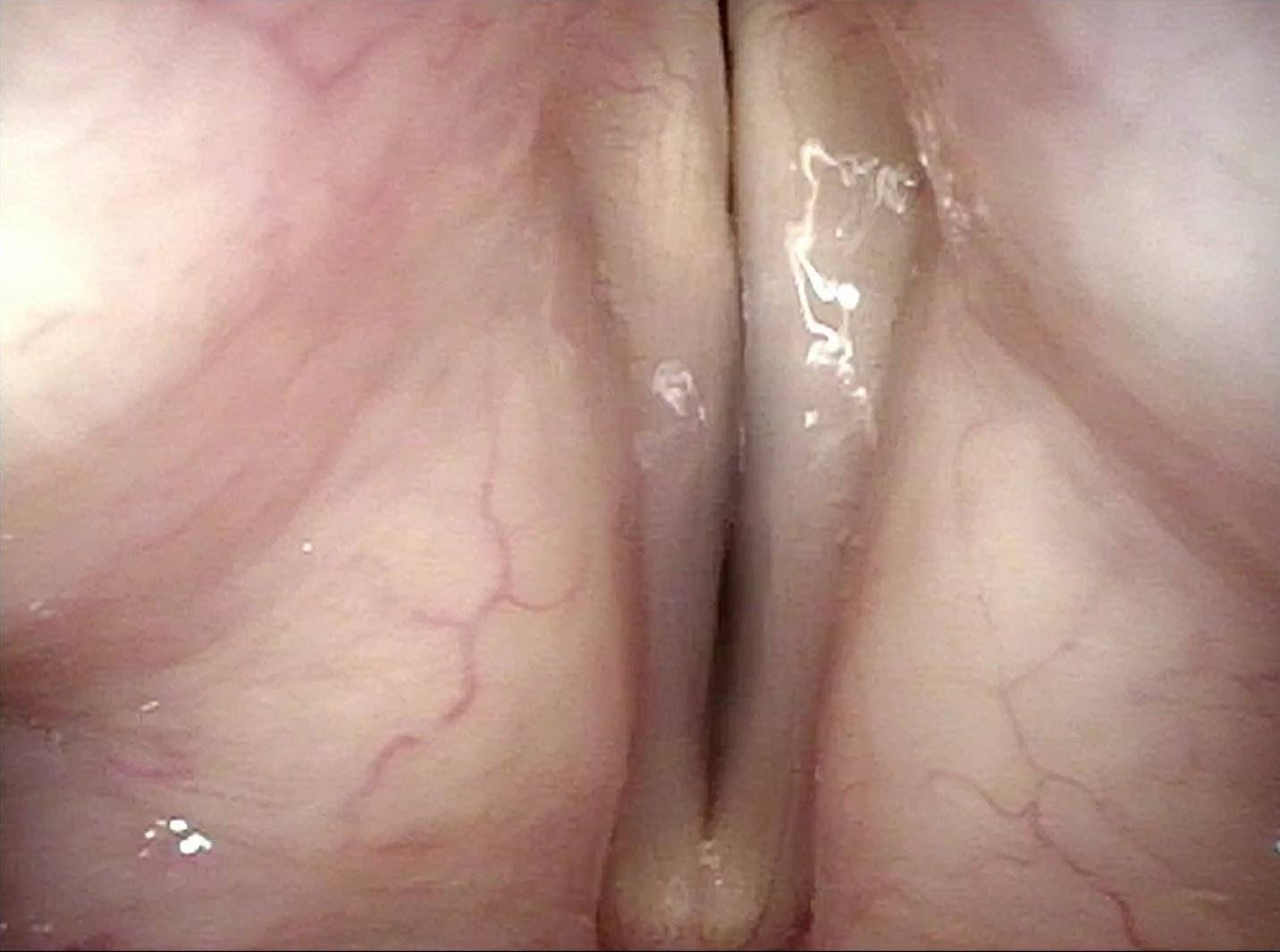

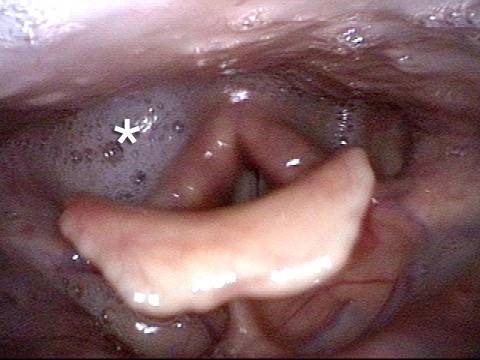

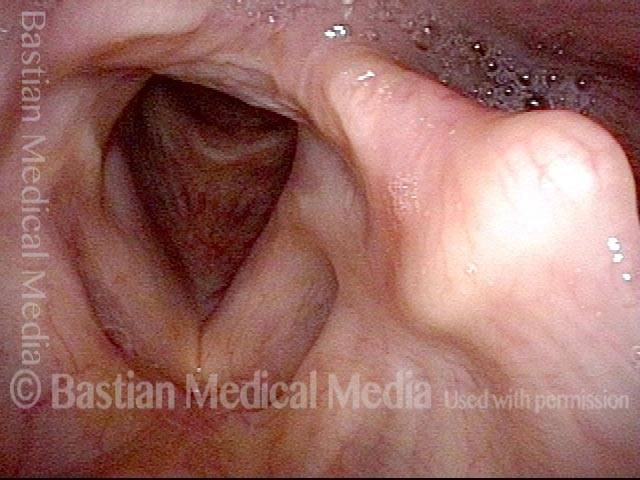

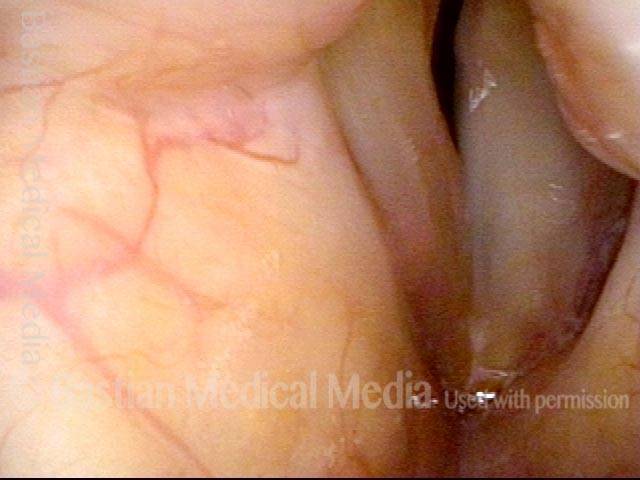

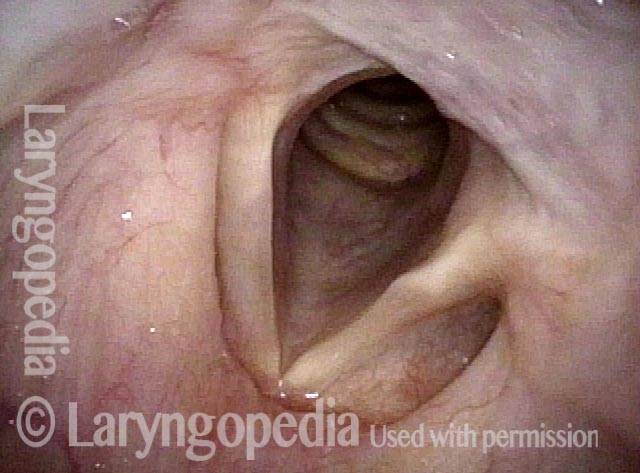

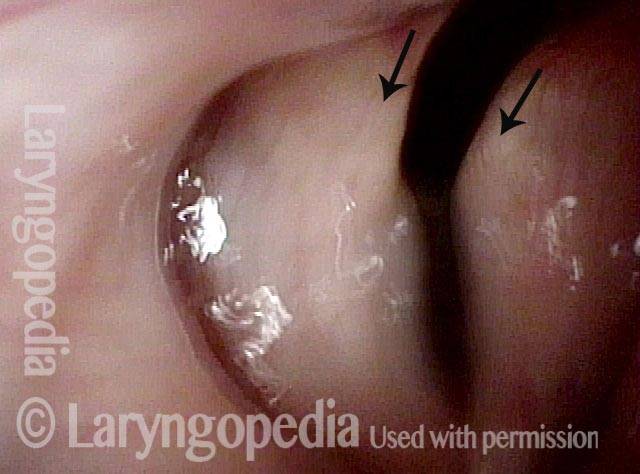

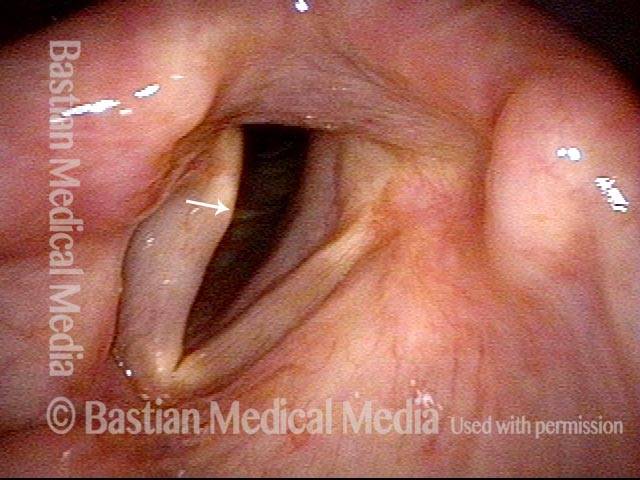

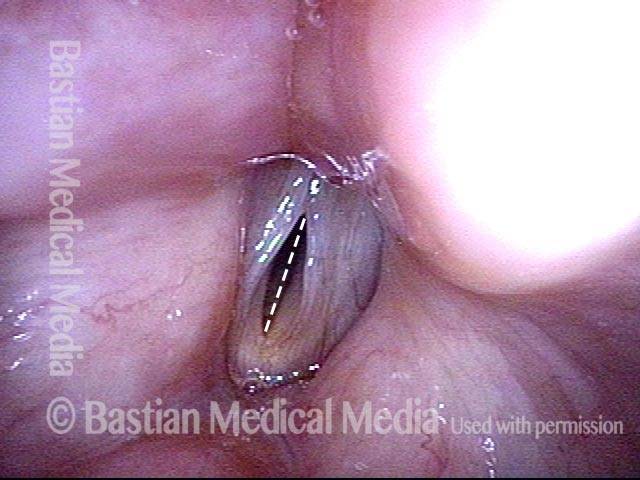

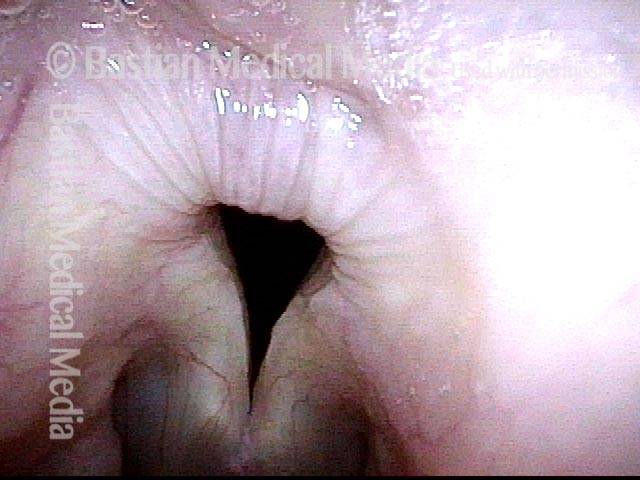

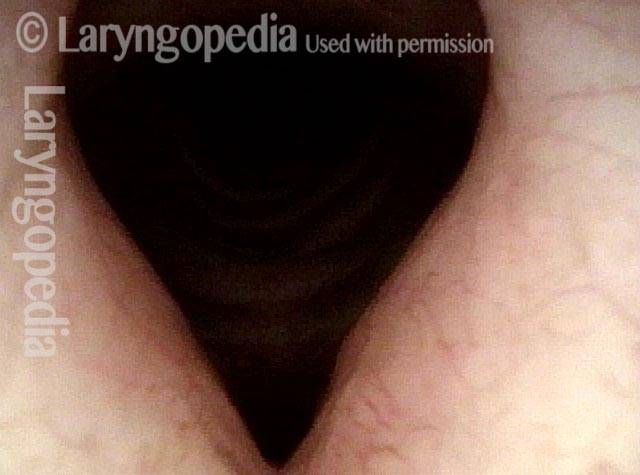

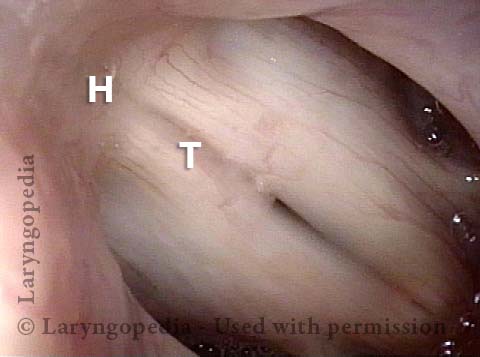

Smaller conus bulge (4 of 5)

Smaller conus bulge (4 of 5)

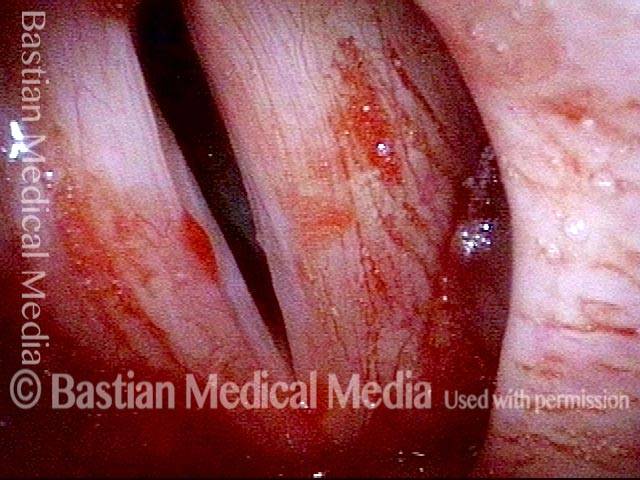

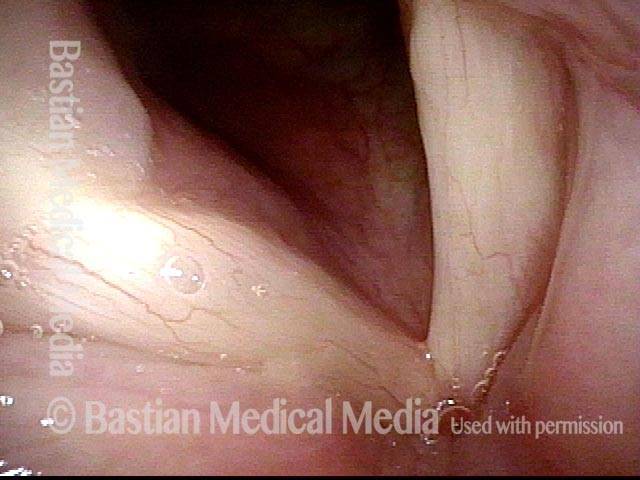

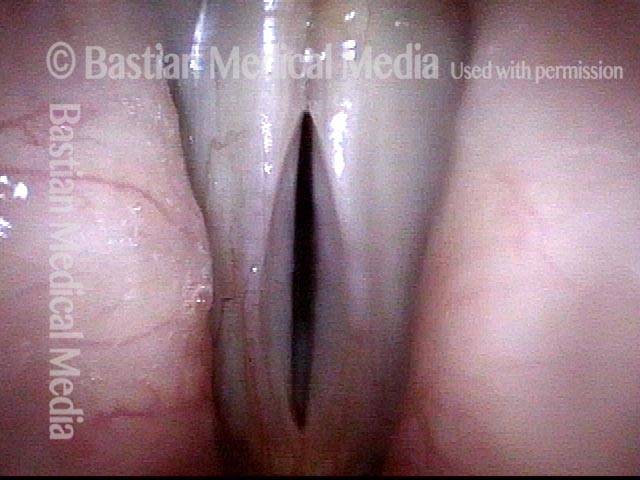

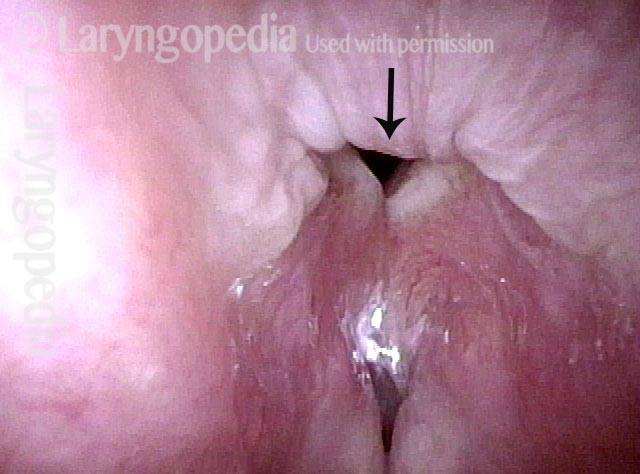

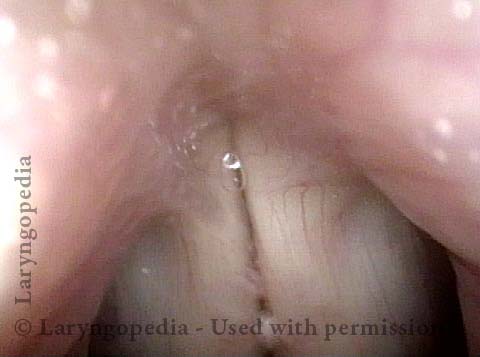

Atrophy + Flaccidity (5 of 5)

Atrophy + Flaccidity (5 of 5)

High Vagus Nerve Injury

The vagus (10th cranial) nerve originates from the medulla (part of the brainstem), exits from the base of the skull through the jugular foramen, and among other things, supplies branches to the musculature of palate, pharynx, and larynx. Location of vagus nerve injury is sometimes evident by palate and pharynx findings. But these findings are sometimes overlooked as in this case, especially if palate and pharynx are weak but not completely paralyzed.

Case study

This 50-something woman developed a weak voice and moderate difficulty swallowing upon awakening 5 months prior to this visit. Fortunately, her symptoms of weak voice and difficulty swallowing were not devastating, and are improving. But up to this examination, there has been no diagnosis. This examination reveals a “lesion” of her right vagus nerve and it has to be at the base of the skull because palate, pharynx, and larynx muscles are all weak.

Voice is functional but lacks the ability to project and has a “soft-edged” quality. A sophisticated listener can also hear mild hypernasality. The examination below prompts a scan with special attention to base of skull to be sure there is no mass lesion there.

Nasopharynx (1 of 7)

Nasopharynx (1 of 7)

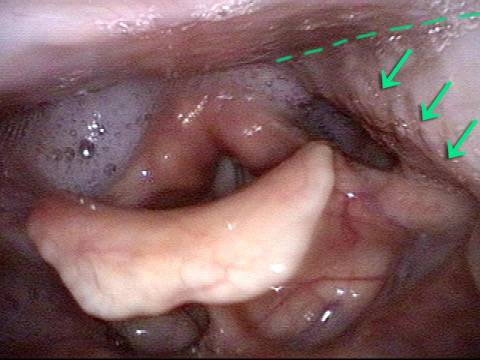

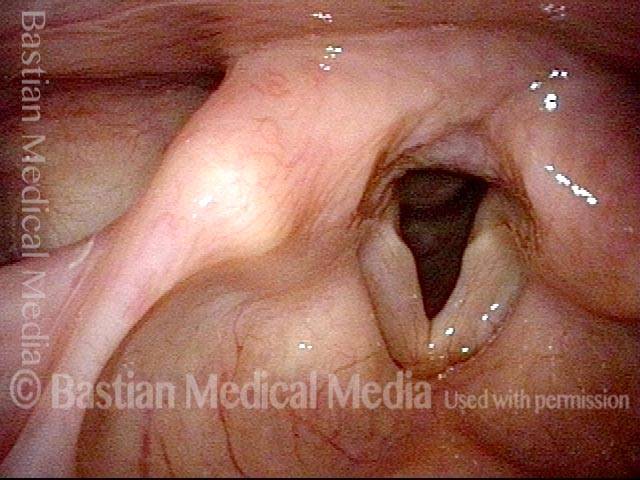

Saliva pooling in right pyriform sinus (2 of 7)

Saliva pooling in right pyriform sinus (2 of 7)

Pharynx contracts (3 of 7)

Pharynx contracts (3 of 7)

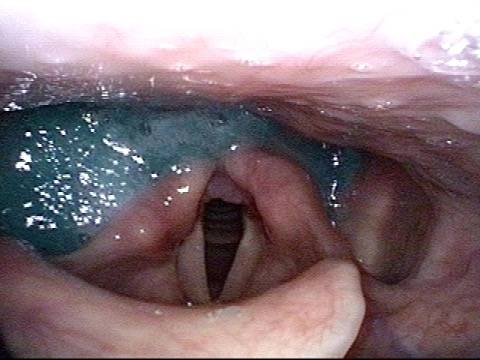

Swallowing blue applesauce (4 of 7)

Swallowing blue applesauce (4 of 7)

Unilateral pharynx contraction (5 of 7)

Unilateral pharynx contraction (5 of 7)

Right vocal cord paresis (6 of 7)

Right vocal cord paresis (6 of 7)

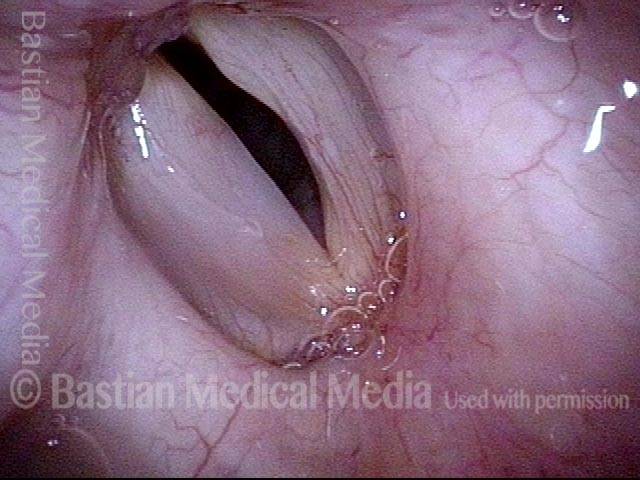

Vocal cord is paretic, not paralyzed (7 of 7)

Vocal cord is paretic, not paralyzed (7 of 7)

Photos of TA + LCA Vocal Cord Paresis

Paresis, TA + LCA (1 of 6)

Paresis, TA + LCA (1 of 6)

Paresis, TA + LCA (2 of 6)

Paresis, TA + LCA (2 of 6)

Paresis, TA + LCA (3 of 6)

Paresis, TA + LCA (3 of 6)

Paresis, TA + LCA: 1 week after implant is placed (4 of 6)

Paresis, TA + LCA: 1 week after implant is placed (4 of 6)

Paresis, TA + LCA: 3 months after implant is placed (5 of 6)

Paresis, TA + LCA: 3 months after implant is placed (5 of 6)

Paresis, TA + LCA: 3 months after implant is placed (6 of 6)

Paresis, TA + LCA: 3 months after implant is placed (6 of 6)

Example 2

Normally functioning PCA muscle (1 of 8)

Normally functioning PCA muscle (1 of 8)

Paresis, TA + LCA (2 of 8)

Paresis, TA + LCA (2 of 8)

Paresis, TA + LCA (3 of 8)

Paresis, TA + LCA (3 of 8)

Paresis, TA + LCA (4 of 8)

Paresis, TA + LCA (4 of 8)

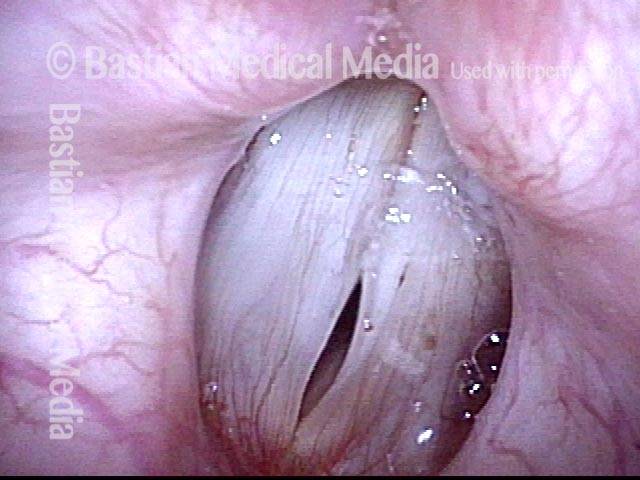

Paresis, TA + LCA: voice gel injection (5 of 8)

Paresis, TA + LCA: voice gel injection (5 of 8)

Paresis, TA + LCA: after voice gel injection (6 of 8)

Paresis, TA + LCA: after voice gel injection (6 of 8)

Paresis, TA + LCA: after voice gel injection (7 of 8)

Paresis, TA + LCA: after voice gel injection (7 of 8)

Paresis, TA + LCA: after voice gel injection (8 of 8)

Paresis, TA + LCA: after voice gel injection (8 of 8)

Example 3

Paresis, TA + LCA (1 of 5)

Paresis, TA + LCA (1 of 5)

Paresis, TA + LCA (2 of 5)

Paresis, TA + LCA (2 of 5)

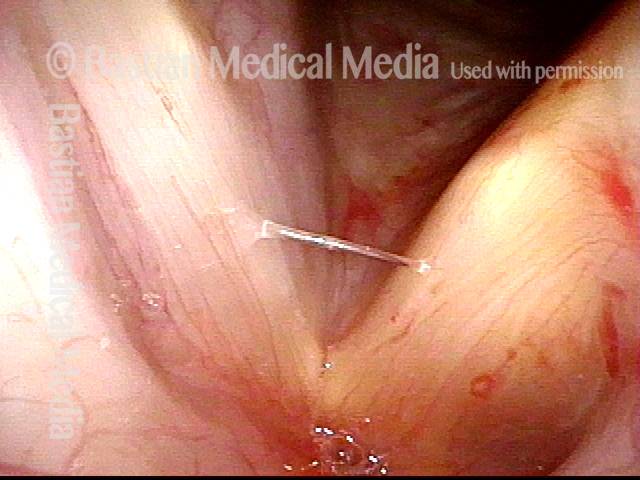

Paresis, TA + LCA: voice gel injection (3 of 5)

Paresis, TA + LCA: voice gel injection (3 of 5)

Paresis, TA + LCA: 1 month after voice gel injection (4 of 5)

Paresis, TA + LCA: 1 month after voice gel injection (4 of 5)

Paresis, TA + LCA: 1 month after voice gel injection (5 of 5)

Paresis, TA + LCA: 1 month after voice gel injection (5 of 5)

Example 4

Paresis, TA + LCA, with recovery (1 of 4)

Paresis, TA + LCA, with recovery (1 of 4)

Paresis, TA + LCA, with recovery (2 of 4)

Paresis, TA + LCA, with recovery (2 of 4)

Paresis, TA + LCA, with recovery (3 of 4)

Paresis, TA + LCA, with recovery (3 of 4)

Paresis, TA + LCA, with recovery (4 of 4)

Paresis, TA + LCA, with recovery (4 of 4)

Example 5

Vocal cord paresis (1 of 2)

Vocal cord paresis (1 of 2)

Vocal cord paresis (2 of 2)

Vocal cord paresis (2 of 2)

Example 6

Paresis, TA + LCA (1 of 7)

Paresis, TA + LCA (1 of 7)

Paresis, TA + LCA (2 of 7)

Paresis, TA + LCA (2 of 7)

Paresis, TA + LCA (3 of 7)

Paresis, TA + LCA (3 of 7)

Paresis, TA + LCA (4 of 7)

Paresis, TA + LCA (4 of 7)

Paresis, TA + LCA: after medialization (5 of 7)

Paresis, TA + LCA: after medialization (5 of 7)

Paresis, TA + LCA: after medialization (6 of 7)

Paresis, TA + LCA: after medialization (6 of 7)

Paresis, TA + LCA: after medialization (7 of 7)

Paresis, TA + LCA: after medialization (7 of 7)

Example 7

TA weakness (1 of 4)

TA weakness (1 of 4)

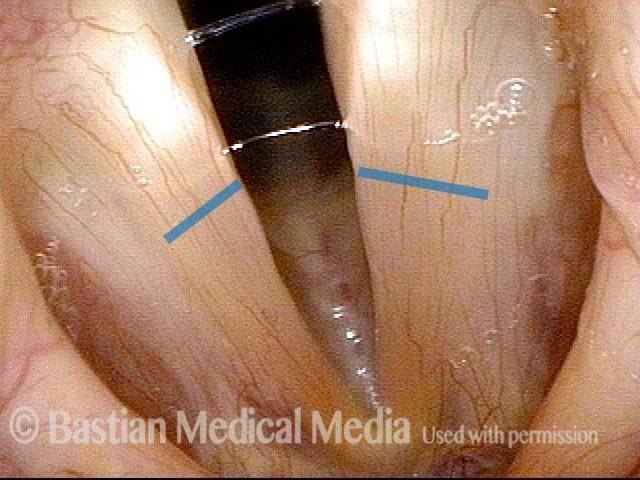

Prephonatory instant (2 of 4)

Prephonatory instant (2 of 4)

LCA not working (3 of 4)

LCA not working (3 of 4)

Phonatory blur (4 of 4)

Phonatory blur (4 of 4)

Example 8

Intubation injury (1 of 4)

Intubation injury (1 of 4)

Forceful exhalation (2 of 4)

Forceful exhalation (2 of 4)

Phonation begins (3 of 4)

Phonation begins (3 of 4)

LCA (4 of 4)

LCA (4 of 4)

Photos of TA-only Vocal Cord Paresis

Paresis, TA-only (1 of 3)

Paresis, TA-only (1 of 3)

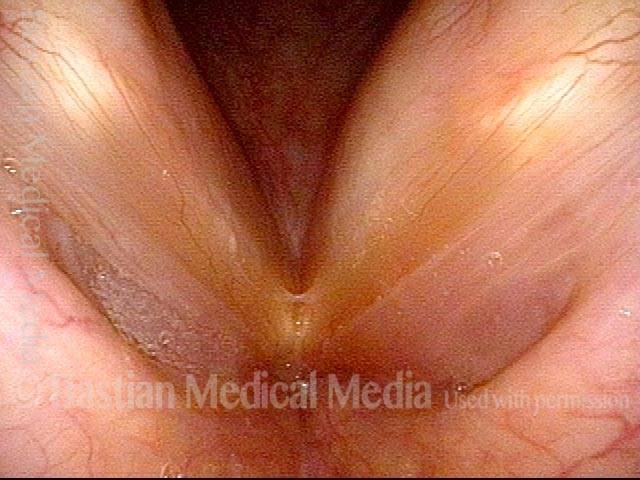

Paresis, TA-only (2 of 3)

Paresis, TA-only (2 of 3)

Paresis, TA-only (3 of 3)

Paresis, TA-only (3 of 3)

Example 2

Paresis, TA-only (1 of 5)

Paresis, TA-only (1 of 5)

Paresis, TA-only (2 of 5)

Paresis, TA-only (2 of 5)

Paresis, TA-only (3 of 5)

Paresis, TA-only (3 of 5)

Paresis, TA-only: after implant is placed (4 of 5)

Paresis, TA-only: after implant is placed (4 of 5)

Paresis, TA-only: after implant is placed (5 of 5)

Paresis, TA-only: after implant is placed (5 of 5)

Photos of LCA-only Vocal Cord Paresis

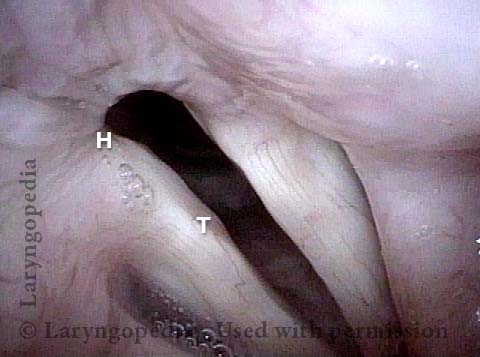

LCA weakness, in a patient with vocal cord paralysis (1 of 4)

LCA weakness, in a patient with vocal cord paralysis (1 of 4)

LCA weakness, masked by high pitch (2 of 4)

LCA weakness, masked by high pitch (2 of 4)

Imposed breathy voice (3 of 4)

Imposed breathy voice (3 of 4)

LCA paresis has recovered (4 of 4)

LCA paresis has recovered (4 of 4)

Photos of PCA-only Vocal Cord Paresis

Paresis, PCA-only (1 of 4)

Paresis, PCA-only (1 of 4)

Paresis, PCA-only (2 of 4)

Paresis, PCA-only (2 of 4)

Paresis, PCA-only (3 of 4)

Paresis, PCA-only (3 of 4)

Paresis, PCA-only (4 of 4)

Paresis, PCA-only (4 of 4)

Example 2

PCA-only paresis years after thyroid lobectomy (1 of 6)

PCA-only paresis years after thyroid lobectomy (1 of 6)

PCA-only paresis years after thyroid lobectomy (2 of 6)

PCA-only paresis years after thyroid lobectomy (2 of 6)

PCA-only paresis years after thyroid lobectomy (3 of 6)

PCA-only paresis years after thyroid lobectomy (3 of 6)

PCA-only paresis years after thyroid lobectomy (4 of 6)

PCA-only paresis years after thyroid lobectomy (4 of 6)

PCA-only paresis years after thyroid lobectomy (5 of 6)

PCA-only paresis years after thyroid lobectomy (5 of 6)

PCA-only paresis years after thyroid lobectomy (6 of 6)

PCA-only paresis years after thyroid lobectomy (6 of 6)

Example 3

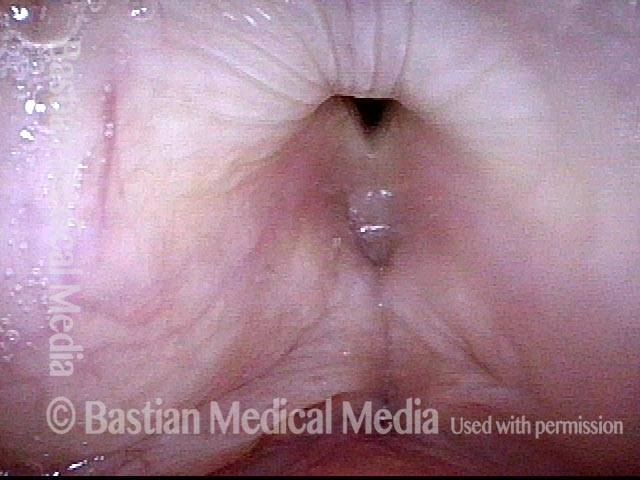

Abducted breathing position (1 of 4)

Abducted breathing position (1 of 4)

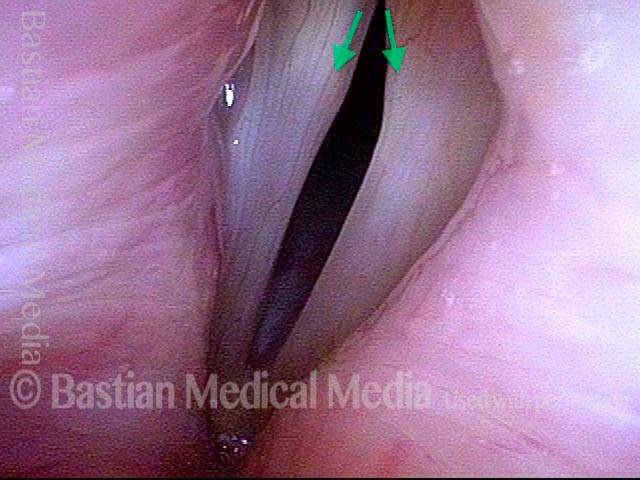

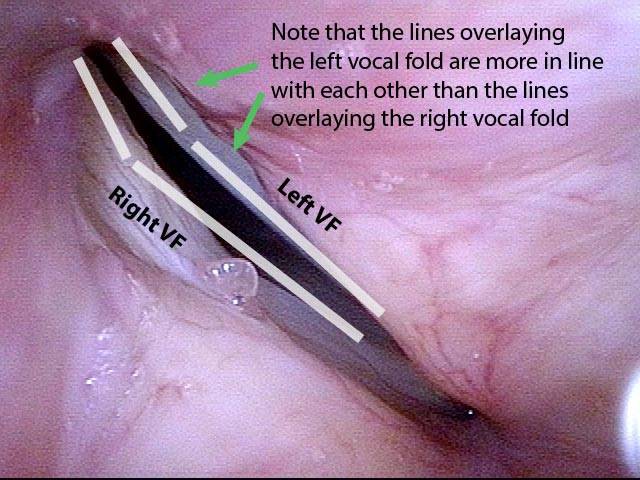

Full approximation of cords, TA is intact (2 of 4)

Full approximation of cords, TA is intact (2 of 4)

Phonation, LCA is intact (3 of 4)

Phonation, LCA is intact (3 of 4)

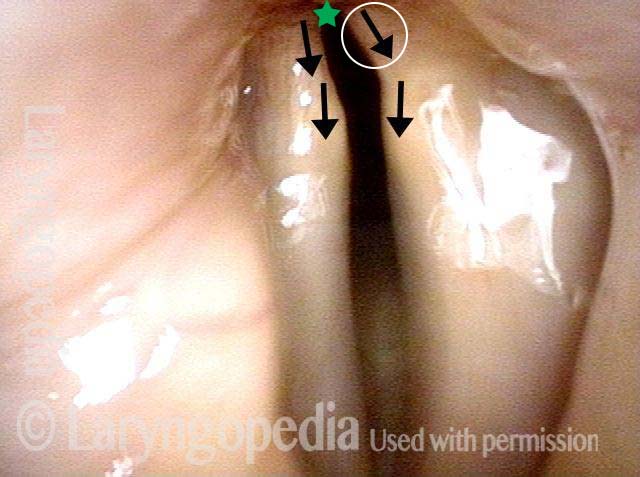

Phonation under strobe light, PCA-only paresis (4 of 4)

Phonation under strobe light, PCA-only paresis (4 of 4)

Photos of IA-only Vocal Cord Paresis

IA-only paresis (1 of 5)

IA-only paresis (1 of 5)

IA-only paresis (2 of 5)

IA-only paresis (2 of 5)

IA-only paresis (3 of 5)

IA-only paresis (3 of 5)

IA-only paresis, during a cough (4 of 5)

IA-only paresis, during a cough (4 of 5)

IA-only paresis, during a Valsalva maneuver (5 of 5)

IA-only paresis, during a Valsalva maneuver (5 of 5)

Example 2

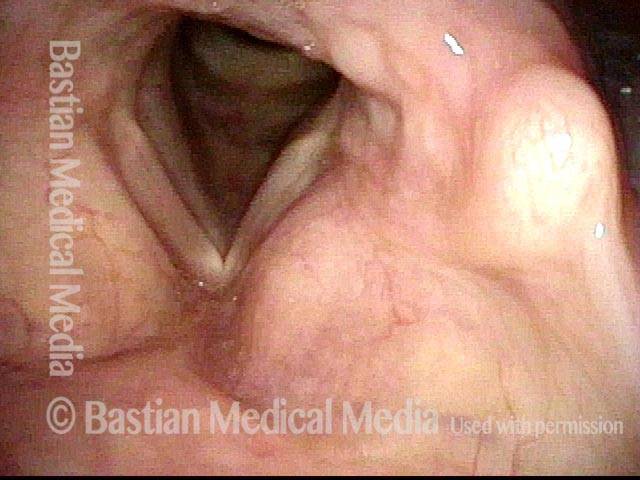

Breathy and weak voice (1 of 8)

Breathy and weak voice (1 of 8)

Bowing (2 of 8)

Bowing (2 of 8)

Pre-phonatory view (3 of 8)

Pre-phonatory view (3 of 8)

Phonatory view (4 of 8)

Phonatory view (4 of 8)

Posterior commissure (5 of 8)

Posterior commissure (5 of 8)

TA function (6 of 8)

TA function (6 of 8)

IA mucosa (7 of 8)

IA mucosa (7 of 8)

IA avulsion (8 of 8)

IA avulsion (8 of 8)

The Rarest Paresis: Interarytenoid (IA) Weakness, Manifested as Inability to Pull the “Heels” of the Arytenoid Cartilages into Contact

Large gap during phonation (1 of 7)

Large gap during phonation (1 of 7)

Interarytenoid muscle (2 of 7)

Interarytenoid muscle (2 of 7)

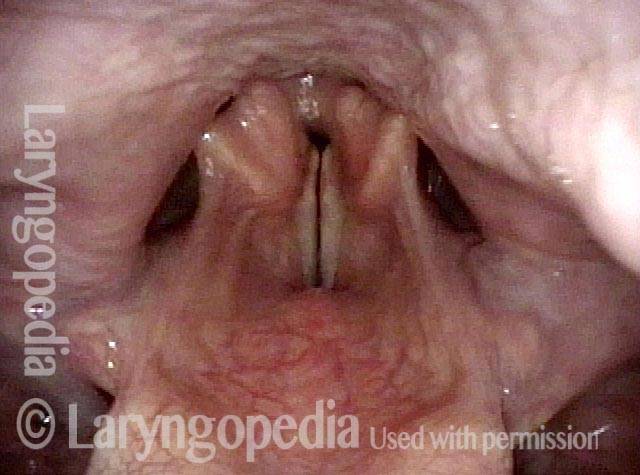

Atrophied right cord (3 of 7)

Atrophied right cord (3 of 7)

IA muscle is not working (4 of 7)

IA muscle is not working (4 of 7)

3 months later (5 of 7)

3 months later (5 of 7)

Recovery of (IA) muscle (6 of 7)

Recovery of (IA) muscle (6 of 7)

Secretional overlay on IA muscle (7 of 7)

Secretional overlay on IA muscle (7 of 7)

Share this article

Injection Medialization for Vocal Cord Paresis

See an example of one variant of vocal cord paresis and how it limits the voice. Then watch a medialization procedure in which voice gel is injected into the vocal cord affected by paresis, and hear how the voice thereafter improves.

Do I Need Surgery for Vocal Cord Paralysis?

There is unfortunately not a lot one can do to speed healing. In the photo essay Vocal Cord Paresis Accentuated by Disuse, the patient had sufficient spontaneous recovery to give her an “adequate” voice. The main thing is NOT to rest the voice as this woman did, as all that does is to atrophy any muscle that remains functional. And one can try “voice building” to see if it adds any strength.

If those things don’t work and it is 9 months or more since the onset of the paralysis, the only options are to accept the “new” voice or to proceed to medialization.

Keep in mind that one type of medialization is a simple injection, and the other is surgery through a one-inch incision.