Voice Building

Voice building is the process of adding strength to the voice by using a variety of tasks that tax its strength capabilities. The idea is that over time the larynx will rise to the challenge and adapt to increased demands, much as might happen to the arms as a result of a weight-lifting regimen.

Sometimes the voice building regimen is very simple and “do-it-yourself”; other times it is more sophisticated and requires the assistance of a speech pathologist who is singing voice qualified.

Vocal Cord Paresis (Thyroarytenoid Muscle) Accentuated by Disuse

This woman illustrates that vocal cords are inhabited by muscle (thyroarytenoid muscle, to be precise). If that muscle atrophies due to paresis (partial loss of nerve supply), this alone can weaken the voice.

That is what happened to her 10 years ago, in her fifties, after thyroid surgery. Initially the left cord did not move (paralysis). Then movement returned and along with it, her voice gradually gained in strength.

When recovery was maximal, the vocal cord abducted (opened) and adducted (closed) normally. She also regained “90%” of her voice; while the muscle within the vocal cord did not recover fully, there was sufficient strength and tone to mostly “keep up” with the demands of her moderate voice use.

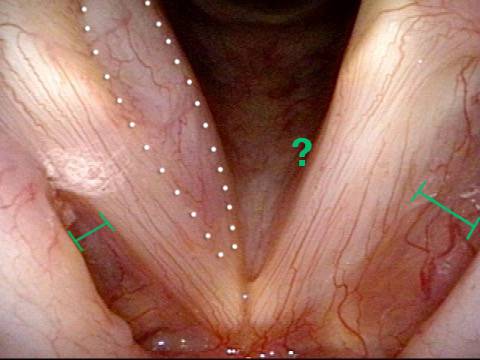

Technically, she began with paralysis (of TA, LCA, and PCA) but after recovery, had a TA-only paresis as shown in photos 1-3 below. All was well for 10 years as she had a perfectly functional voice.

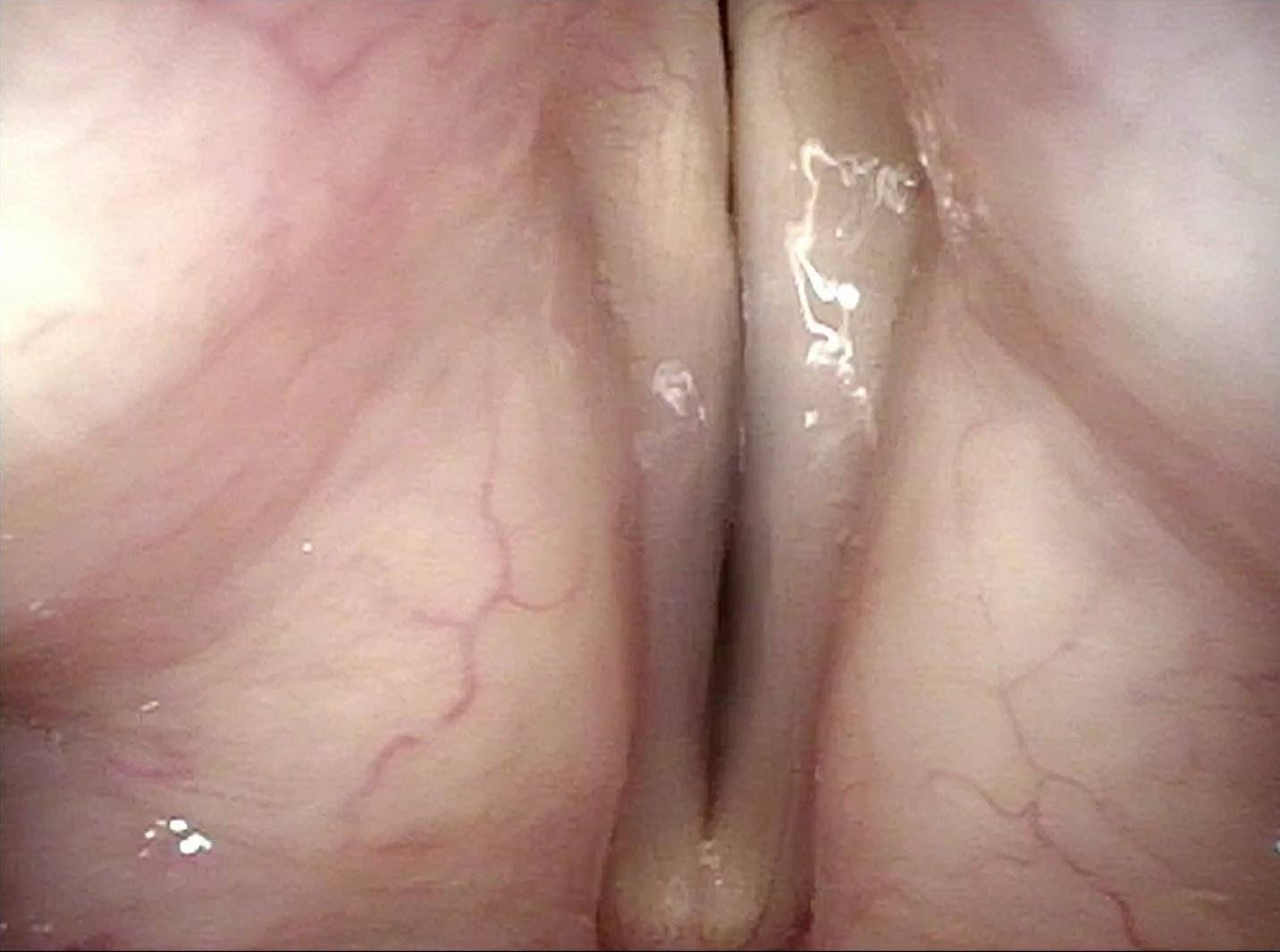

Ten years later, now in her sixties, she developed a bad URI (not Covid-19) and voice deteriorated in the midst of hard bouts of coughing. At the same time, due to retirement, and self-quarantine, she was using voice very little.

Two months later, still using voice very little and even intentionally “resting it,” her voice is extremely weak. The explanation is that by figuratively putting her voice in bed, she has added disuse atrophy to the longstanding paresis. How do we know this? The answer is in photos 4-5 below. And the appropriate initial treatment? Voice building exercises.

Conus bulge in the larynx (1 of 5)

Conus bulge in the larynx (1 of 5)

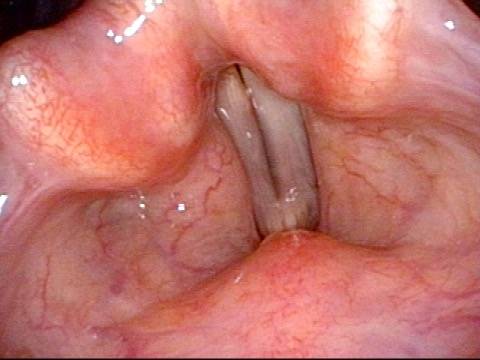

Left vocal cord adducts normally (2 of 5)

Left vocal cord adducts normally (2 of 5)

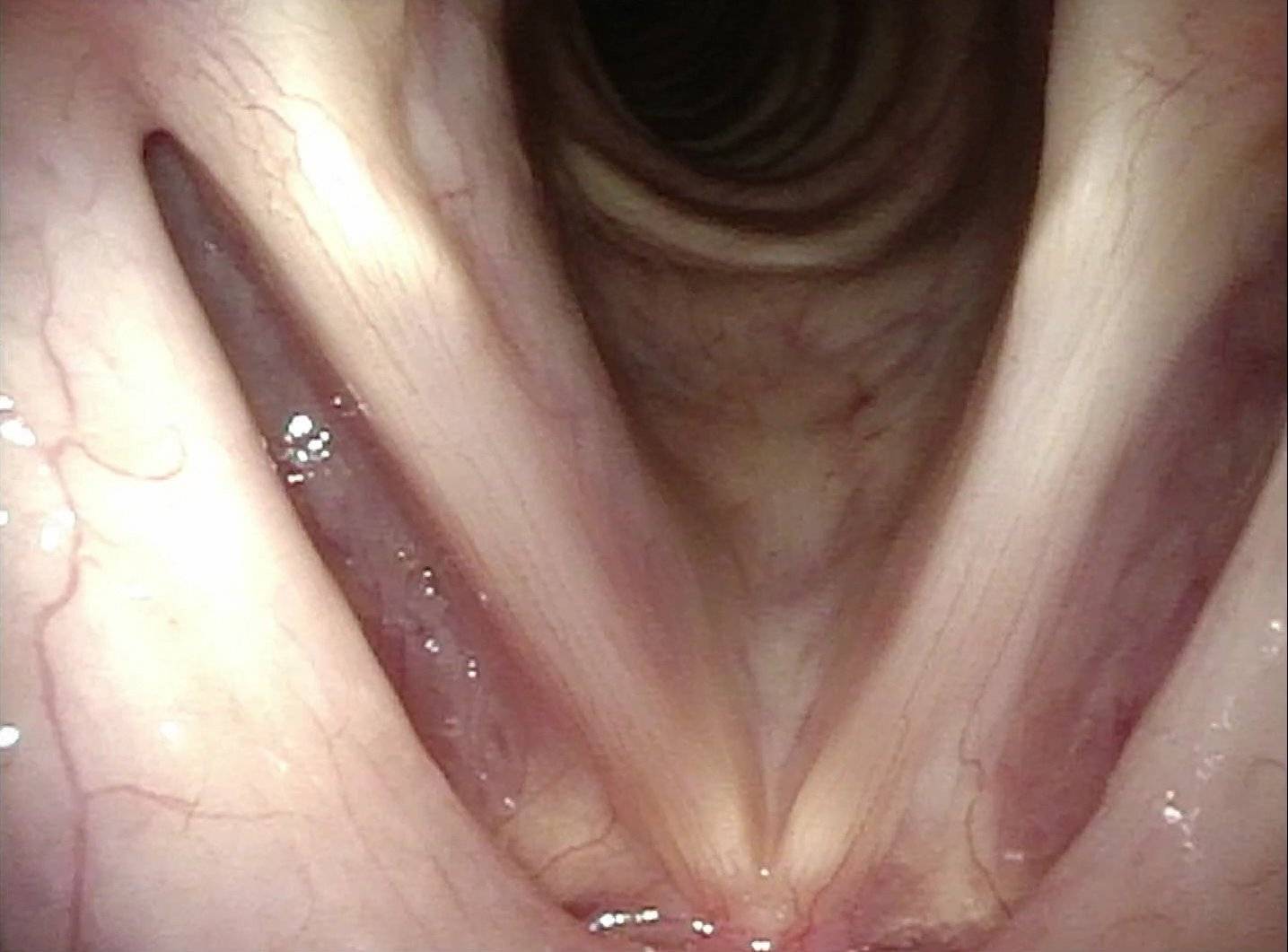

Voice remains strong despite atrophy (3 of 5)

Voice remains strong despite atrophy (3 of 5)

Smaller conus bulge (4 of 5)

Smaller conus bulge (4 of 5)

Atrophy + Flaccidity (5 of 5)

Atrophy + Flaccidity (5 of 5)

Share this article

Voice Building Exercises

Voice Building Exercises

3 Simple Exercises to Strengthen A Weak Voice

A weak voice that can’t be heard in noisy places, or that “fades” in quality and strength across a day can be frustrating!

There is a long list of potential explanations. A common one is weak, atrophied, flaccid vocal cord—and other vocal tract—muscles. When this is the cause for a weak voice determined by medical evaluation, voice building is the first place to start.

In this video, Dr. Bastian provides background information about muscle building in general, and why vocal muscles can weaken in some people.

Loss of Upper Voice Caused by Lowered Muscular Ceiling (MTD)

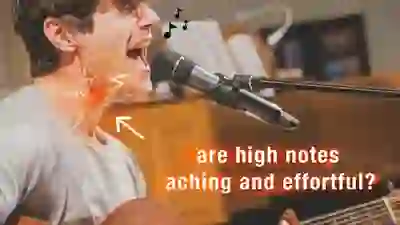

Every voice has a natural range (from its “floor” to its “ceiling”), often 2 ½ octaves or more. Over time, some singers notice upper range loss or effortfulness (the ceiling descends). Yet there are no nodules or polyps.

When the “muscular ceiling” descends, it feels and sounds like the voice has to be pushed up to its upper range and the throat may almost ache with the effort. And pitch may sag. A common association in women is menopause, but it can be seen in either sex at any age.

Does voice building change pitch?

A stronger voice often also sounds richer and this translates to “deeper” without necessarily a change in pitch. Low voice tends to become stronger, though.

Can voice building be applicable for someone with unilateral vocal fold paralysis?

Of course a paralyzed cord cannot be strengthened. The functioning side could be, and that might help marginally. It can’t hurt to try these but if the improvement is other than very modest, it might be due to some recovery on the paralyzed side.

Is there a such a thing as too aggressive in voice building?

Technically, yes, but limiting to a minute or two per session would make it EXTREMELY unlikely. Especially if you do what is described. You are calling vigorously across the street; speaking in a loud “arguing” voice, and doing a loud siren. You aren’t screaming …