TA-only Paresis

Weakness or paralysis of the vocal cord’s thyroarytenoid (TA) muscle, but with normal function of the vocal cord’s other muscles. The TA muscle “inhabits” the vocal cord and normally provides bulk and internal tone to the cord. The following are indicators of TA-only paresis:

- Movement: The vocal cord opens normally for breathing and closes normally for voicing.

- Position and appearance: Position is normal. Typically, the margin of the cord is slightly concave, the ventricle is capacious, and the conus area below the free margin is lacking in bulk.

- Appearance during voicing (under strobe lighting): Closure at the posterior commissure is complete and symmetrical bilaterally. Under strobe light, one sees flaccidity as indicated by increased amplitude of vibration; the lateral excursions become exaggerated and the mucosal wave increases. One may also see chaotic fluttering.

- Voice quality: Weak and air-wasting and often indistinguishable from a case of complete vocal cord paralysis—TA, LCA (lateral cricoarytenoid), and PCA (posterior cricoarytenoid).

Other variants of vocal cord paresis include LCA-only, TA + LCA, PCA-only, and IA-only (interarytenoid muscle).

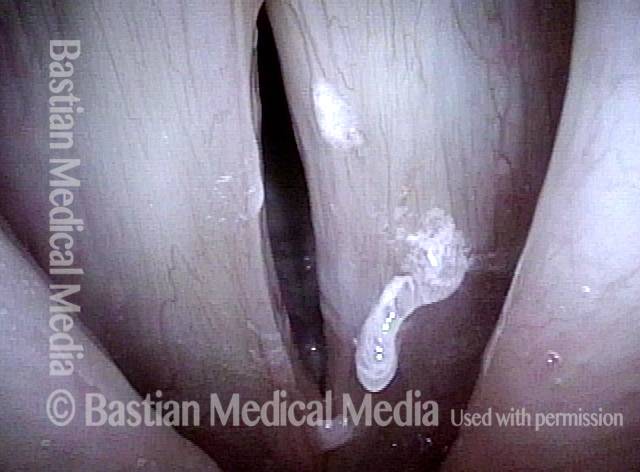

TA-only Paresis after Botox Injection for Spasmodic Dysphonia

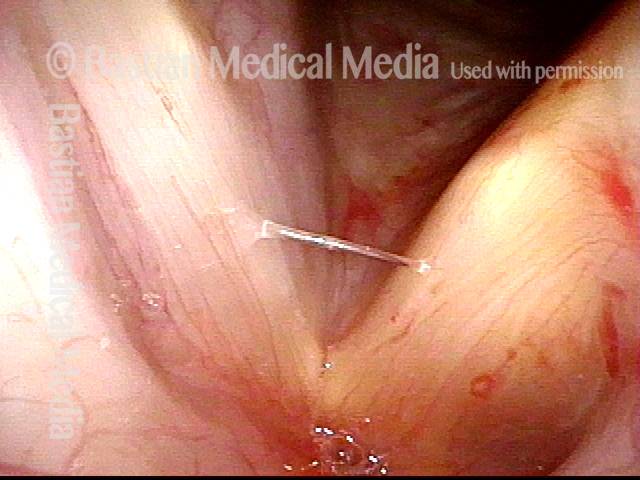

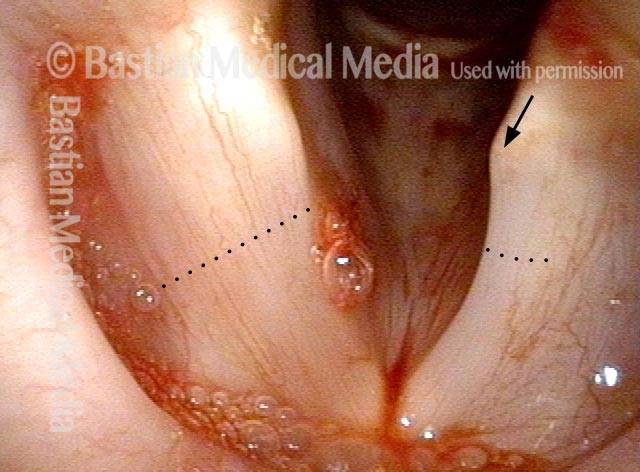

This man with adductory spasmodic dysphonia, has had consistent results during 15 years of botulinum toxin injections, administered several times per year. After his most recent (routine, and unremarkable) injection with his longstanding dose, his initial weakness was exaggerated and is only beginning to subside after six weeks. This dramatic “outlier” result that cannot be attributed to botox targeting. As seen in the photos below, the explanation is instead a right TA-only paresis.

The only reasonable interpretation is that the needle tip has “sheared” the branch of the recurrent laryngeal nerve supplying the thyroarytenoid muscle (leaving branches to the posterior cricoarytenoid and lateral cricoarytenoid muscles (PCA + LCA) undisturbed.

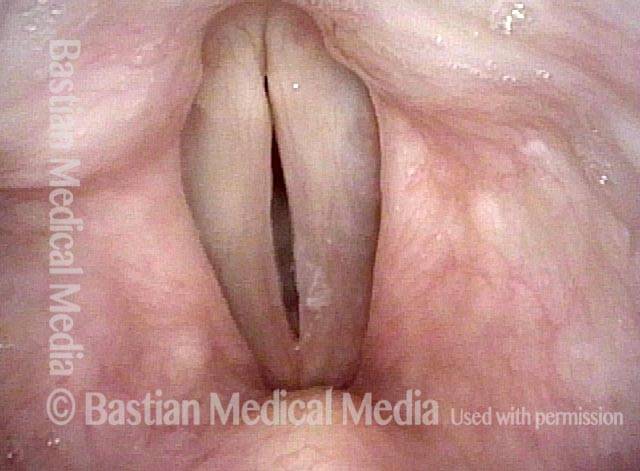

In a practice that supplies treatment to approximately 100 patients per month and ~1200 injections per year, this phenomenon occurs perhaps twice per year. The voice “always” recovers back to baseline SD symptomatology, but excessive breathiness starts to resolve only 6 weeks after the injection.

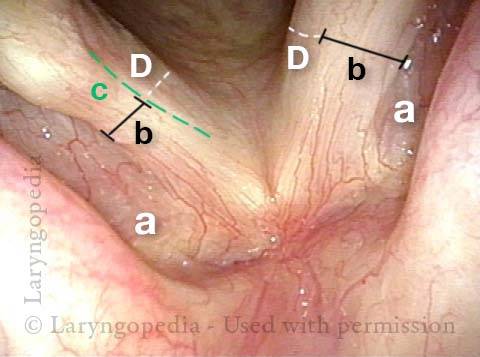

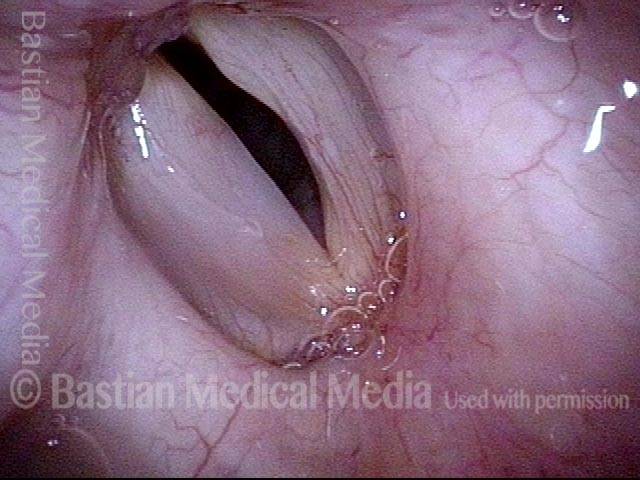

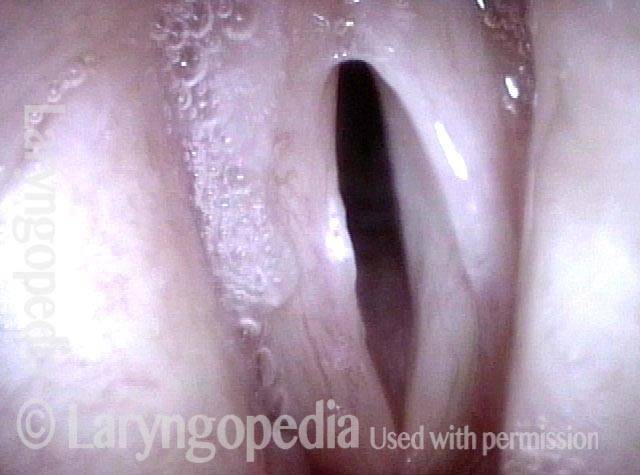

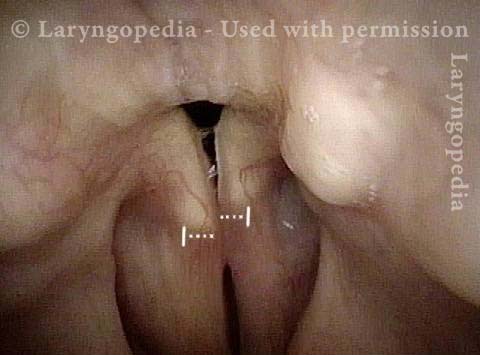

Right Thyroarytenoid Atrophy (1 of 3)

Right Thyroarytenoid Atrophy (1 of 3)

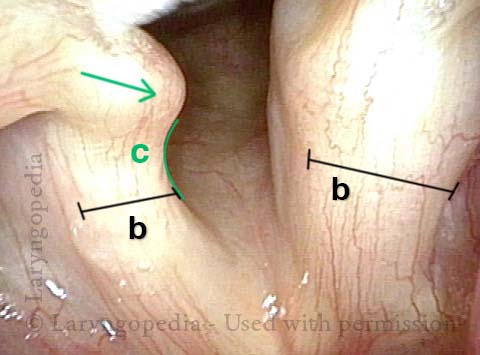

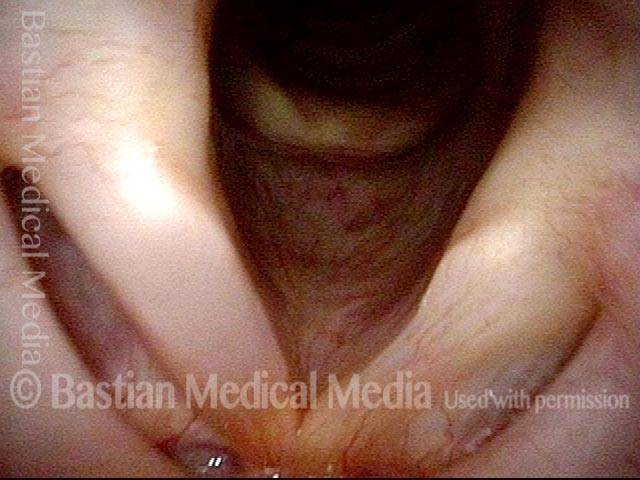

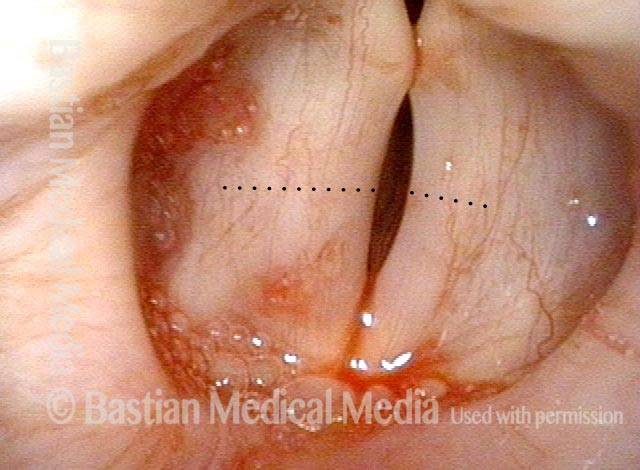

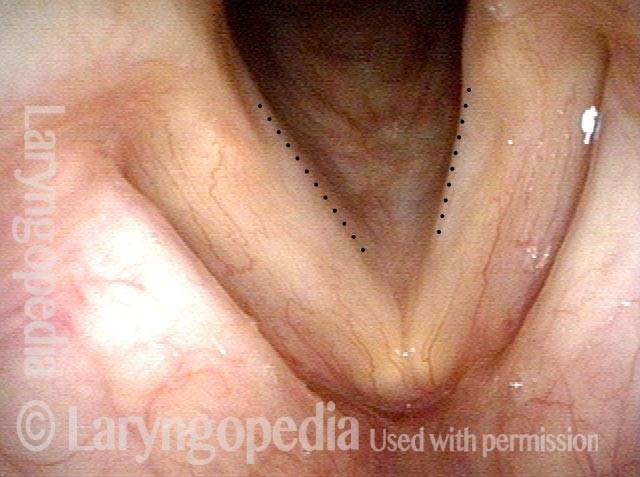

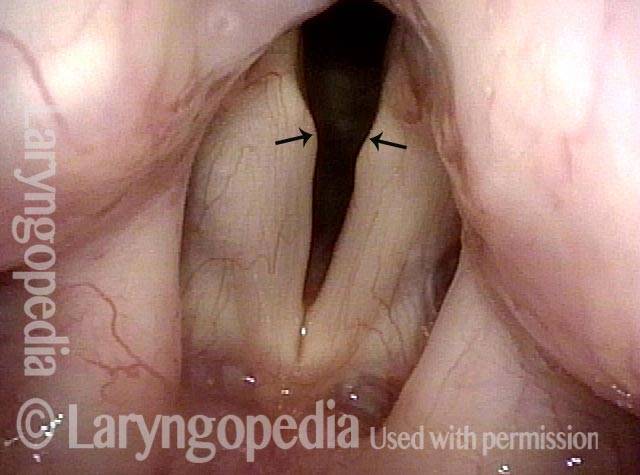

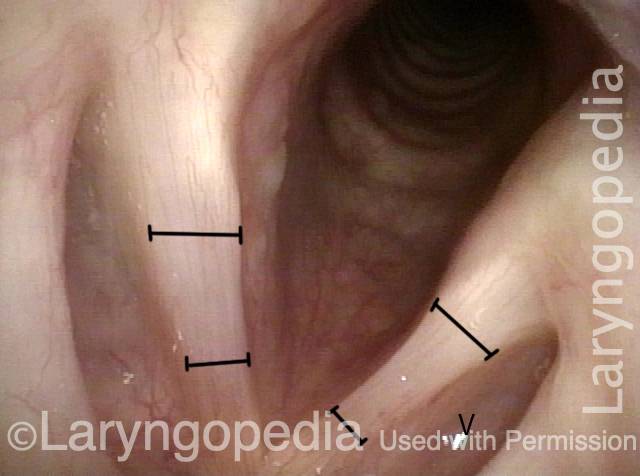

Sharp medial turning (2 of 3)

Sharp medial turning (2 of 3)

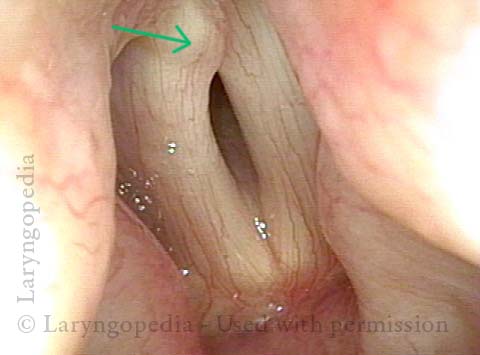

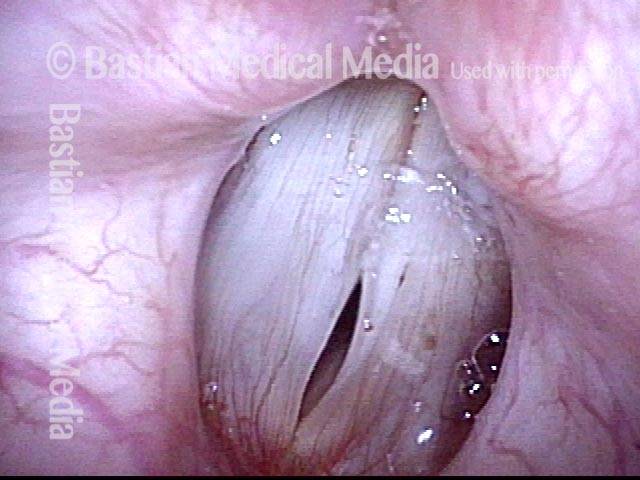

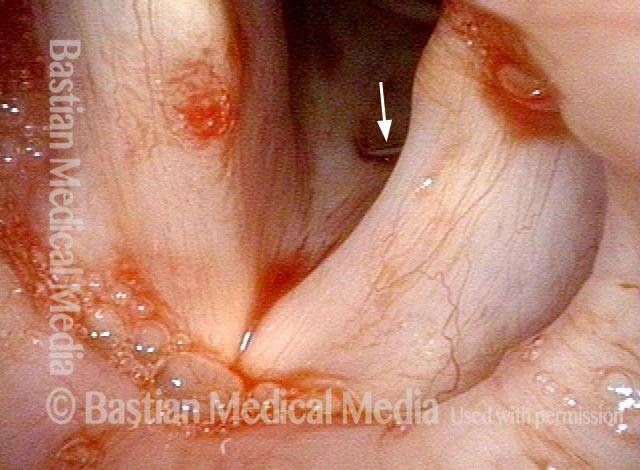

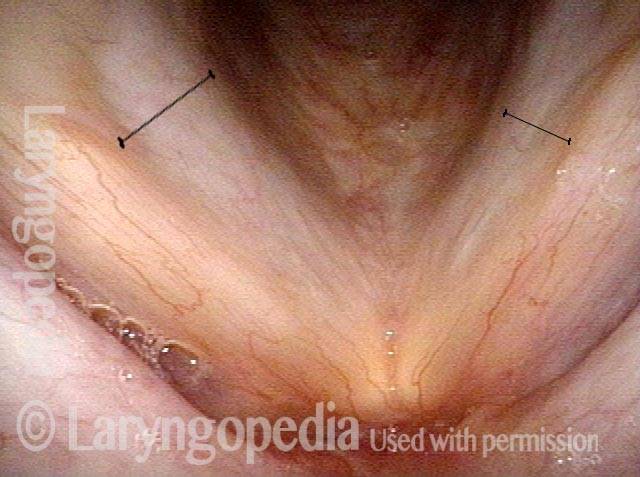

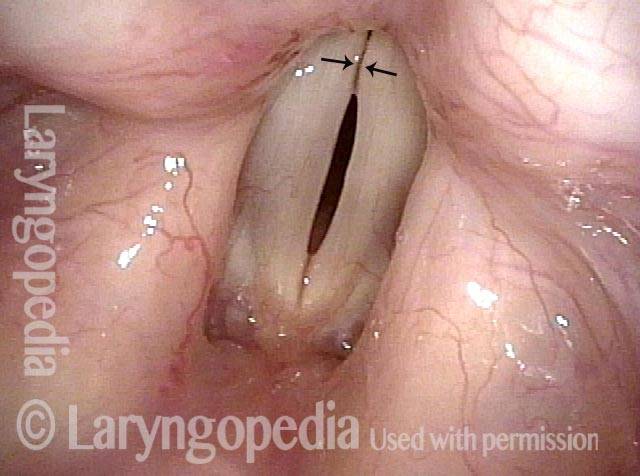

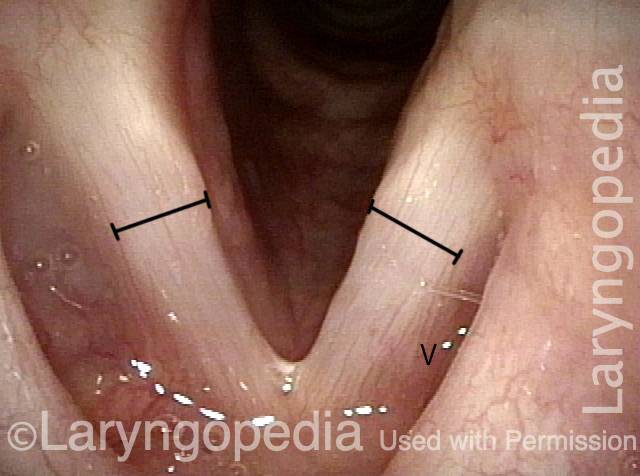

Right vocal process overlaps left vocal process (3 of 3)

Right vocal process overlaps left vocal process (3 of 3)

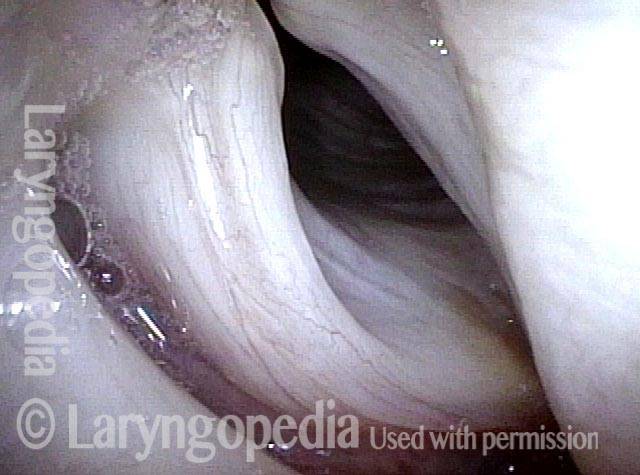

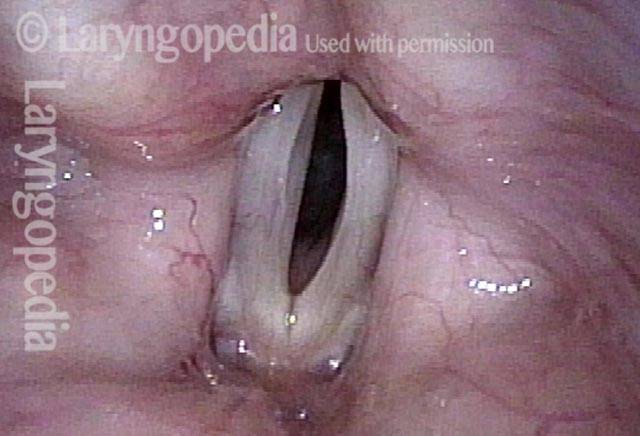

Paresis, TA-only

Paresis, TA-only (1 of 3)

Paresis, TA-only (1 of 3)

Paresis, TA-only (2 of 3)

Paresis, TA-only (2 of 3)

Paresis, TA-only (3 of 3)

Paresis, TA-only (3 of 3)

Paresis, TA-only: before and after an Implant

Paresis, TA-only (1 of 5)

Paresis, TA-only (1 of 5)

Paresis, TA-only (2 of 5)

Paresis, TA-only (2 of 5)

Paresis, TA-only (3 of 5)

Paresis, TA-only (3 of 5)

Paresis, TA-only: after implant is placed (4 of 5)

Paresis, TA-only: after implant is placed (4 of 5)

Paresis, TA-only: after implant is placed (5 of 5)

Paresis, TA-only: after implant is placed (5 of 5)

Vocal Cord Paresis (Thyroarytenoid Muscle) Accentuated by Disuse

This woman illustrates that vocal cords are inhabited by muscle (thyroarytenoid muscle, to be precise). If that muscle atrophies due to paresis (partial loss of nerve supply), this alone can weaken the voice. That is what happened to her 10 years ago, in her fifties, after thyroid surgery. Initially the left cord did not move (paralysis). Then movement returned and along with it, her voice gradually gained in strength.

When recovery was maximal, the vocal cord abducted (opened) and adducted (closed) normally. She also regained “90%” of her voice; while the muscle within the vocal cord did not recover fully, there was sufficient strength and tone to mostly “keep up” with the demands of her moderate voice use. Technically, she began with paralysis (of TA, LCA, and PCA) but after recovery, had a TA-only paresis as shown in photos 1-3 below. All was well for 10 years as she had a perfectly functional voice.

Ten years later, now in her sixties, she developed a bad URI (not Covid-19) and voice deteriorated in the midst of hard bouts of coughing. At the same time, due to retirement, and self-quarantine, she was using voice very little. Two months later, still using voice very little and even intentionally “resting it,” her voice is extremely weak.

The explanation is that by figuratively putting her voice in bed, she has added disuse atrophy to the longstanding paresis. How do we know this? The answer is in photos 4-5 below. And the appropriate initial treatment? Voice building exercises.

Conus bulge in the larynx (1 of 5)

Conus bulge in the larynx (1 of 5)

Left vocal cord adducts normally (2 of 5)

Left vocal cord adducts normally (2 of 5)

Voice remains strong despite atrophy (3 of 5)

Voice remains strong despite atrophy (3 of 5)

Smaller conus bulge (4 of 5)

Smaller conus bulge (4 of 5)

Atrophy + Flaccidity (5 of 5)

Atrophy + Flaccidity (5 of 5)

TA-only Paresis before and after Voice Gel Injection

TA weakness, intact LCA + PCA (1 of 5)

TA weakness, intact LCA + PCA (1 of 5)

Prephonatory instant (2 of 5)

Prephonatory instant (2 of 5)

Gel injection (3 of 5)

Gel injection (3 of 5)

Straight vocal cord margin (4 of 5)

Straight vocal cord margin (4 of 5)

Phonation (5 of 5)

Phonation (5 of 5)

Just Bowing? No, TA-only Paresis

Prephonatory view (1 of 4)

Prephonatory view (1 of 4)

Phonation (2 of 4)

Phonation (2 of 4)

Bowing and Atrophy (3 of 4)

Bowing and Atrophy (3 of 4)

Open phase (4 of 4)

Open phase (4 of 4)

“Mostly-TA” Paresis

Atrophy (1 of 4)

Atrophy (1 of 4)

TA atrophy (2 of 4)

TA atrophy (2 of 4)

LCA intact (3 of 4)

LCA intact (3 of 4)

Closed phase (4 of 4)

Closed phase (4 of 4)

TA-only Paresis, before and after Recovery

Bowing and atrophy (1 of 4)

Bowing and atrophy (1 of 4)

Dramatic flaccidity (2 of 4)

Dramatic flaccidity (2 of 4)

Bowing reduced (3 of 4)

Bowing reduced (3 of 4)

Equalized amplitude (4 of 4)

Equalized amplitude (4 of 4)

Another TA-only Paresis

Left vocal cord paralysis (1 of 4)

Left vocal cord paralysis (1 of 4)

Working LCA muscles (2 of 4)

Working LCA muscles (2 of 4)

Deficient TA muscle (3 of 4)

Deficient TA muscle (3 of 4)

Open phase of vibration (4 of 4)

Open phase of vibration (4 of 4)

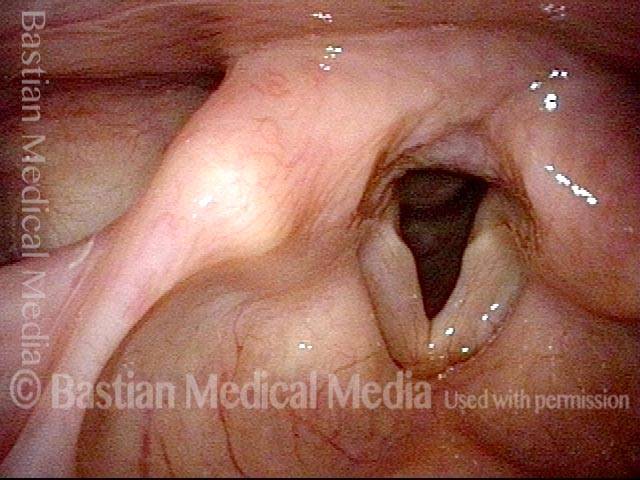

Arytenoid Mismatch Makes for Gravelly Voice Quality Is Hard to Fix in Some Cases of Vocal Cord Paralysis

One could medialize more aggressively posteriorly on the left, hoping to raise the level of the cord, but often attempts to compensate for arytenoid mismatch such as that seen here are only modestly successful. Arytenoid superstructure is not useful for assessment of match; instead, the examiner should judge match at the vocal processes.

Arytenoids do not align (1 of 5)

Arytenoids do not align (1 of 5)

Vocal processes (2 of 5)

Vocal processes (2 of 5)

Vocal processes do not match when touching (3 of 5)

Vocal processes do not match when touching (3 of 5)

Vocal cords out of alignment (4 of 5)

Vocal cords out of alignment (4 of 5)

Asymmetrical vibration (5 of 5)

Asymmetrical vibration (5 of 5)

Vocal Cord Atrophy Goes Away when Nerve Supply to the Thyroarytenoid Muscle Returns

Bowed Margin (1 of 2)

Bowed Margin (1 of 2)

Thyroarytenoid muscle (2 of 2)

Thyroarytenoid muscle (2 of 2)

Share this article