R-CPD Esophageal Findings

The details of the following photos may support the R-CPD diagnosis, though they should not be considered diagnostic.

Take note that all photos are non-channel scope images; that is, the scope is not able to insufflate (blow in) air.

The significance

The esophagus is typically collapsed around endoscopes inserted into them and air is pumped in through a tiny channel in order to gently expand the esophagus so that its walls can be seen. Here, the air the patient cannot belch/evacuate is doing that work for us. And the esophagus remains open for extended time, the full duration of the examination.

Four findings are being evaluated and compared with normal esophagoscopy images (also without insufflated air to make the comparison valid):

- Reflux from the lower esophagus, suggesting damage to the lower esophageal sphincter from constant upward pressure trying unsuccessfully to belch.

- What we call an “aortic shelf,” meaning that rather than an indentation of the medial circumference of the aorta, dilation of the esophagus drapes its mucosa across the upper surface of the esophagus, making a “horizontal shelf.” Keep in mind again that this is without insufflating any air.

- Continuous patency with very infrequent, partial “clamping” down of the lumen or, often no closure at all, suggesting that there is sustained opening pressure of unbelchable air and/or that the contractile ability of the esophagus is reduced, in similar fashion to what happens to an overly-distended urinary bladder.

- Upper esophageal dilation in a medial-lateral axis so that the upper esophagus becomes stretched in an exaggerated “oval” rather than a more gentle oval or even “circle.”

Dramatic lateral stretch of the esophagus

Swallowed air (a fraction of every human swallow) must either be burped, absorbed, or (after some time) passed as flatulence. In a person with retrograde cricopharyngeus dysfunction (R-CPD: defined syndromically as inability to belch, gurgling, bloating, flatulence, etc.) the esophagus will eventually dilate.

This esophageal stretching can hurt, especially during hiccups. And the esophageal wall muscle thins out and its ability to contract weakens. The lower esophageal sphincter (LES) can also fail, leading to reflux of stomach acid from stomach up into the esophagus. Standard manometry typically describes low esophageal and LES pressures and slow transit. These findings are not the diagnosis, but instead are findings that result from the fundamental diagnosis: R-CPD.

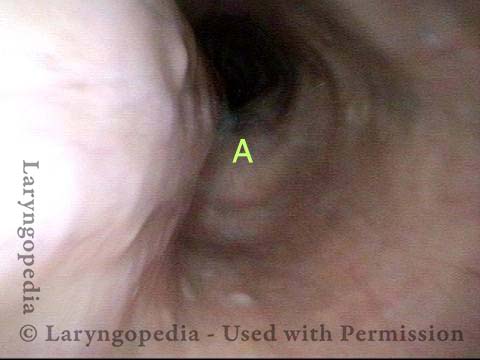

Normal Esophageal View (1 of 3)

Normal Esophageal View (1 of 3)

Reflux in stretched esophagus (2 of 3)

Reflux in stretched esophagus (2 of 3)

Stretched Esophagus (3 of 3)

Stretched Esophagus (3 of 3)

Dramatic esophageal dilation from R-CPD, even in a young person!

The central problem for persons with R-CPD is (obviously) the inability to burp. Bits of air travel through the upper esophageal sphincter (cricopharyngeus muscle) which closes behind each swallow.

Even as the air builds up, expanding the esophagus and sending increasing signals of the need to burp, the air is unable to “get back out” via burping. Initial discomfort from stuck burps-in-waiting may elicit reflexive “extra” swallows that only add more air that cannot be burped.

Gradually this dilates the esophagus (and eventually the stomach, and as air traverses the GI tract, the intestines all the way to the rectum, where it must be released as flatulence). Even in young people, esophageal dilation can be dramatic, causing chest discomfort.

The images below are from the office examination of a teenager sitting in the examination chair with a small ENT scope in his esophagus. The column of air he cannot burp up is holding the esophagus widely open. No air has been insufflated through the scope. The stretched esophagus throws structures outside it into high relief as seen below.

Stretched esophagus (1 of 3)

Stretched esophagus (1 of 3)

Mid-esophagus (2 of 3)

Mid-esophagus (2 of 3)

Stretching esophagus (3 of 3)

Stretching esophagus (3 of 3)

Airway, Foodway, Cricopharyngeus Muscle, and Esophagus in R-CPD

This young woman has never been able to burp normally. She experiences typical, severe R-CPD symptoms of daily bloating, loud gurgling noises, and excessive flatulence. Botulinum toxin injection of the cricopharyngeus muscle is planned to rid her of the syndrome of R-CPD in the short term, and to teach her how to burp “permanently” (even after the botulinum toxin has worn off).

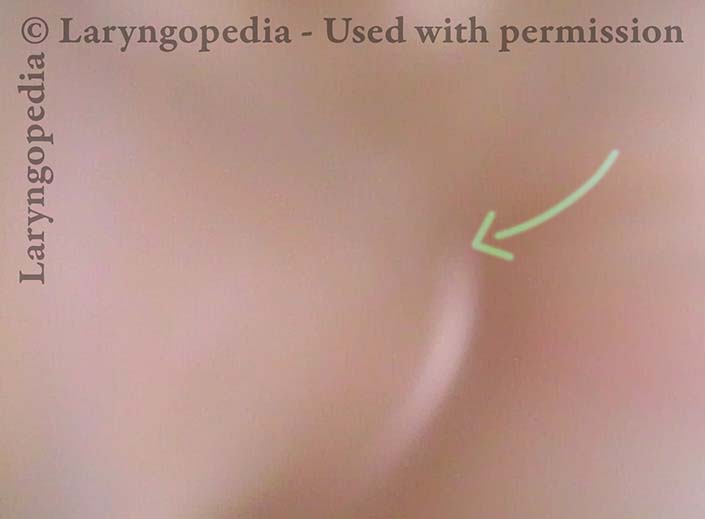

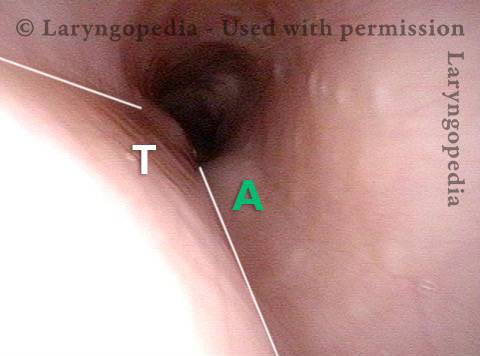

Laryngopharynx (1 of 5)

Laryngopharynx (1 of 5)

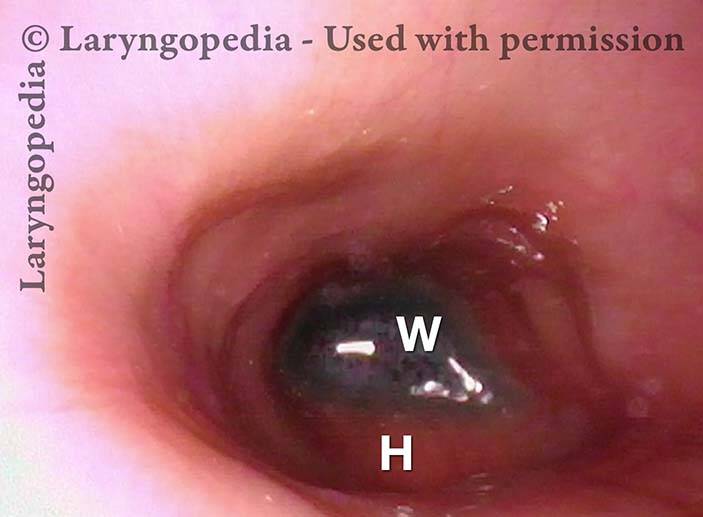

Esophageal opening (2 of 5)

Esophageal opening (2 of 5)

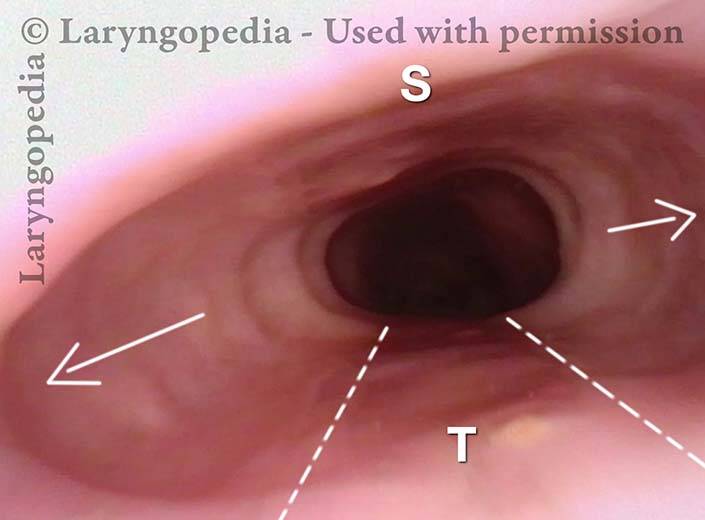

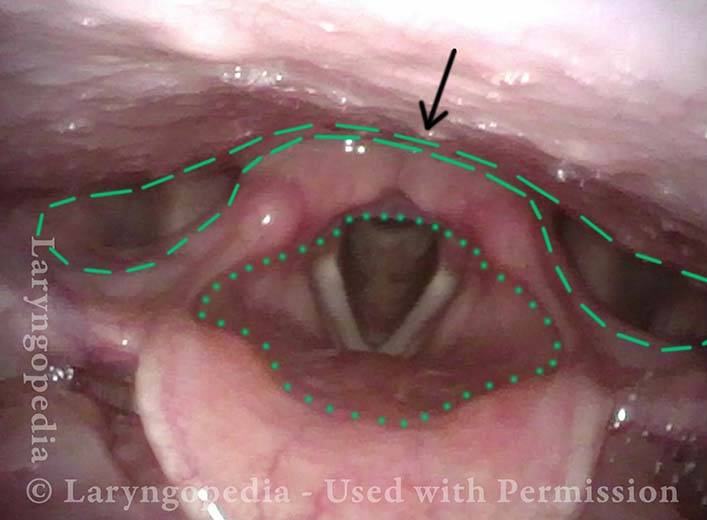

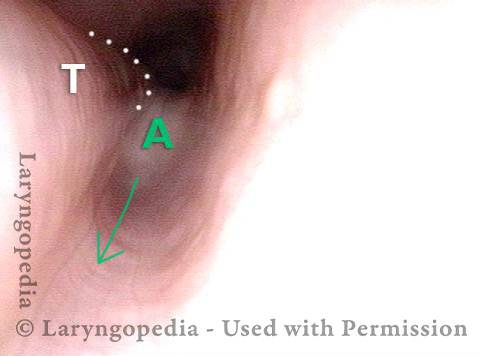

Ridge of UES (3 of 5)

Ridge of UES (3 of 5)

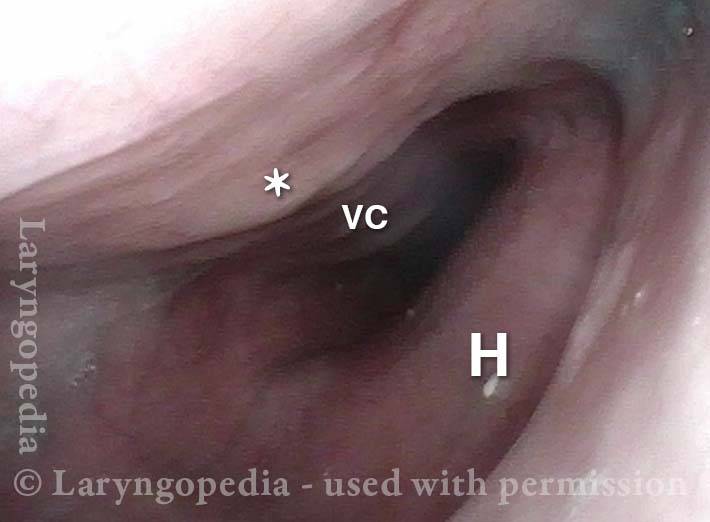

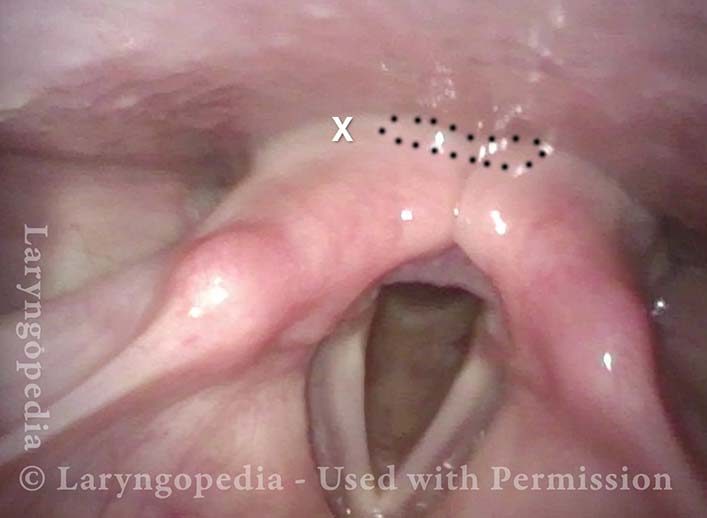

Ridge of UES (4 of 5)

Ridge of UES (4 of 5)

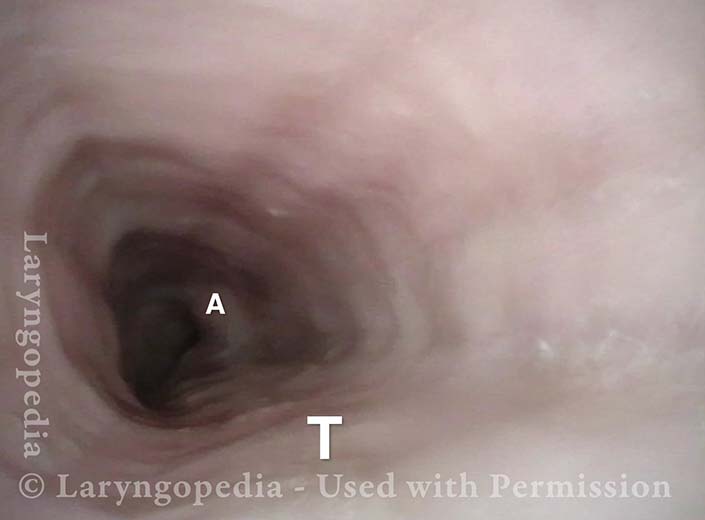

Distended Esophagus (5 of 5)

Distended Esophagus (5 of 5)

Esophageal Stretching by Unburpable Air in R-CPD

This young man has had the classic syndrome of R-CPD lifelong. His esophageal findings at the end of a videoendoscopic swallow study are classic. The esophagus is mostly a collapsed muscular tube in young people, yet his esophagus is widely open on a continuous basis due swallowed air that he cannot burp up.

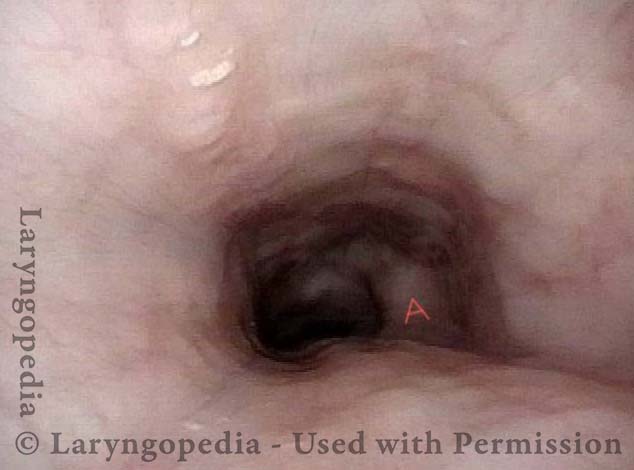

Typical view of an esophagus (1 of 4)

Typical view of an esophagus (1 of 4)

Lower esophagus (2 of 4)

Lower esophagus (2 of 4)

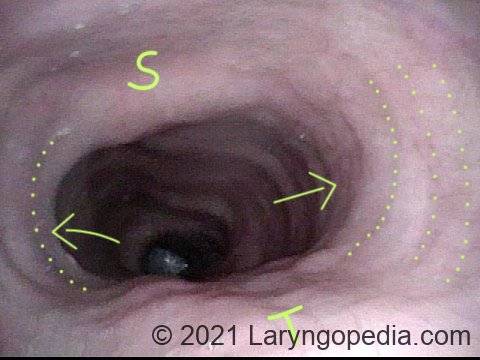

Stretched mid-esophagus (3 of 4)

Stretched mid-esophagus (3 of 4)

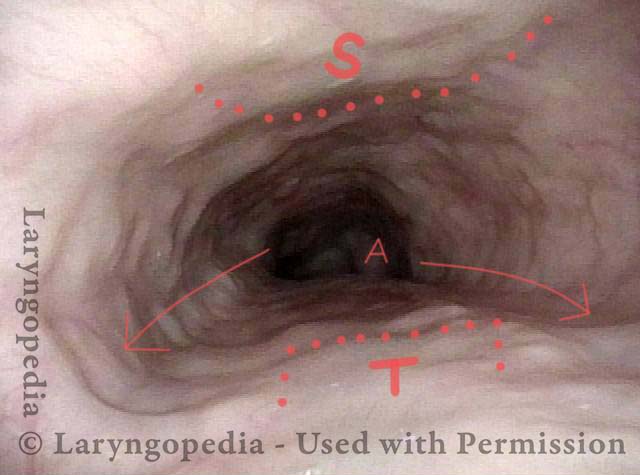

Esophagus stretches laterally (4 of 4)

Esophagus stretches laterally (4 of 4)

More Interesting Esophageal Findings of R-CPD (Inability to Burp)

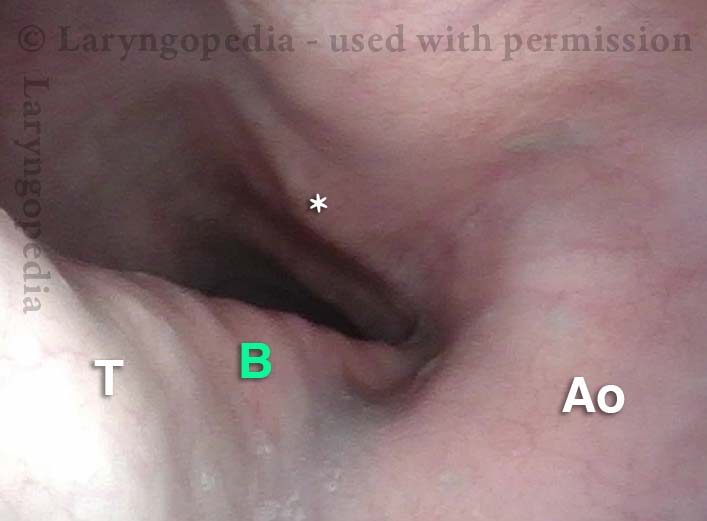

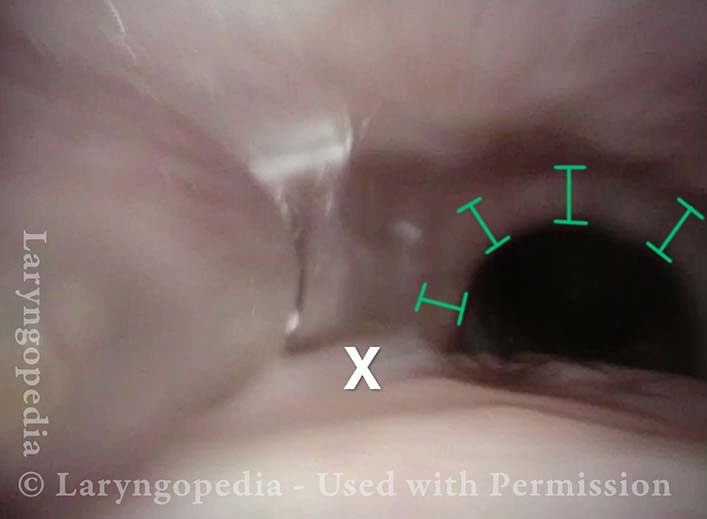

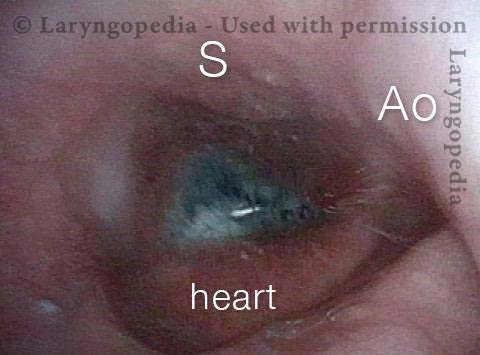

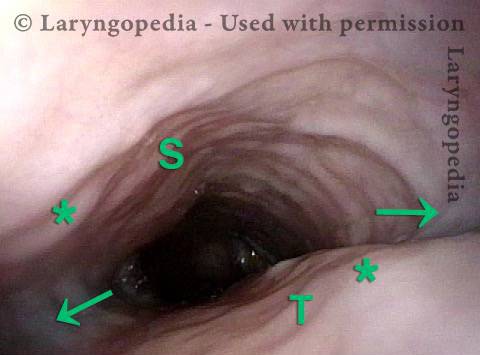

Stretched Esophagus (1 of 4)

Stretched Esophagus (1 of 4)

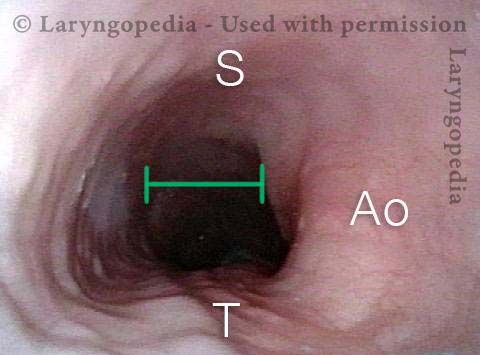

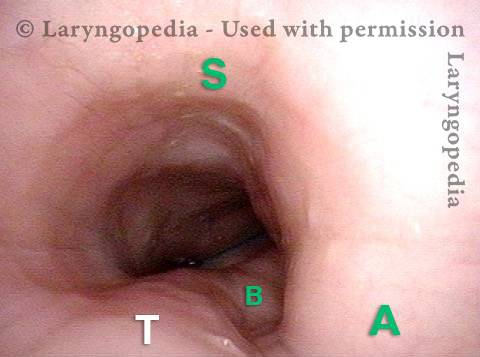

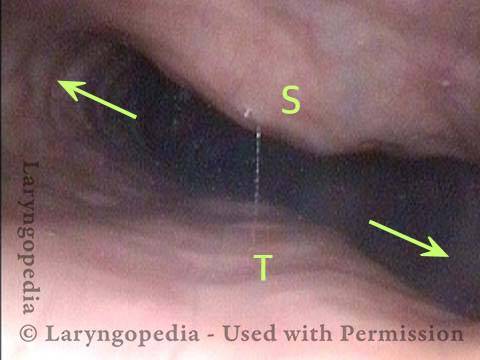

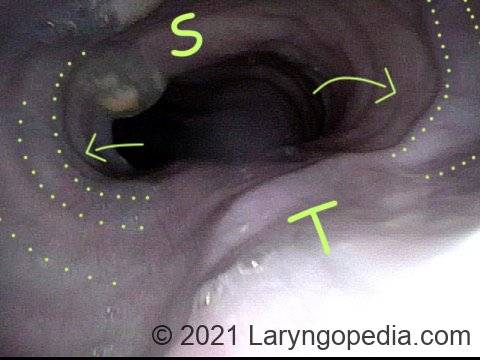

Tracheal Wall (2 of 4)

Tracheal Wall (2 of 4)

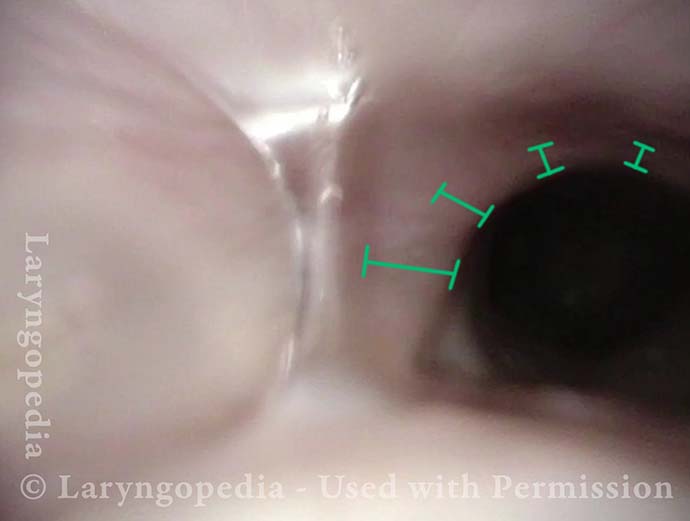

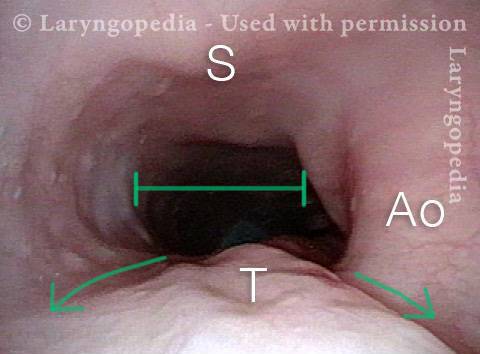

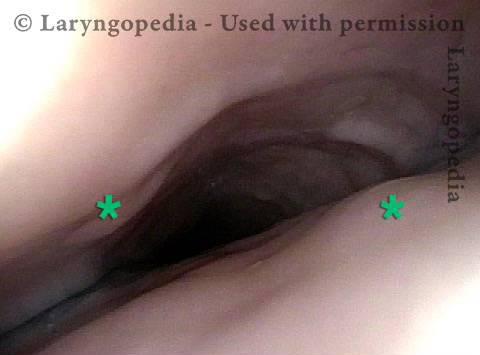

Over-dilation (3 of 4)

Over-dilation (3 of 4)

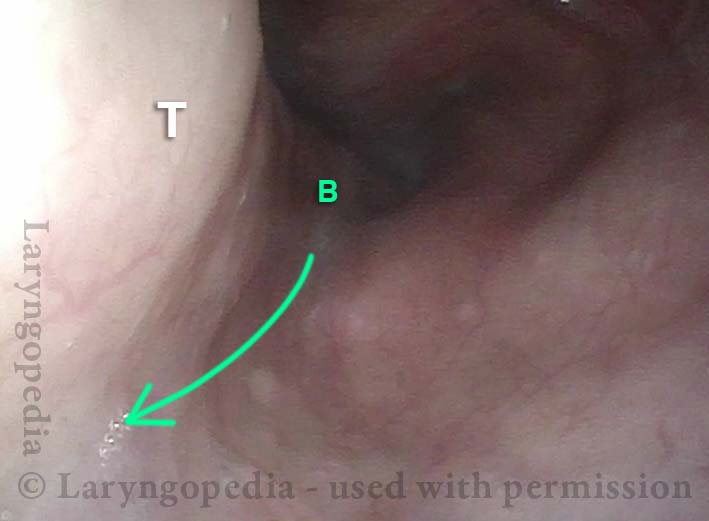

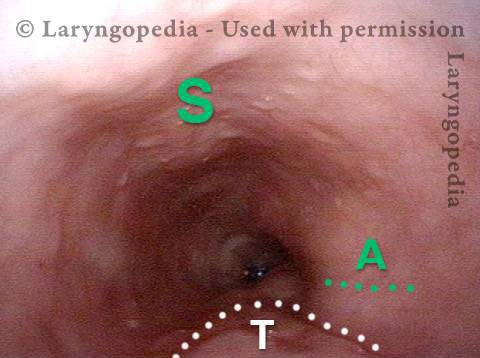

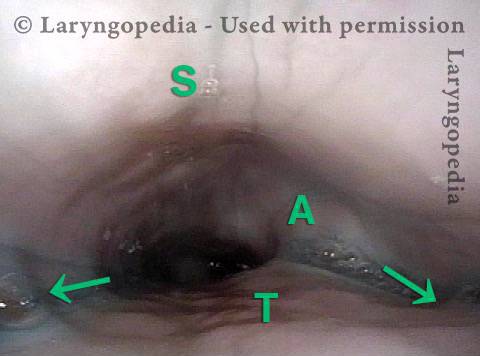

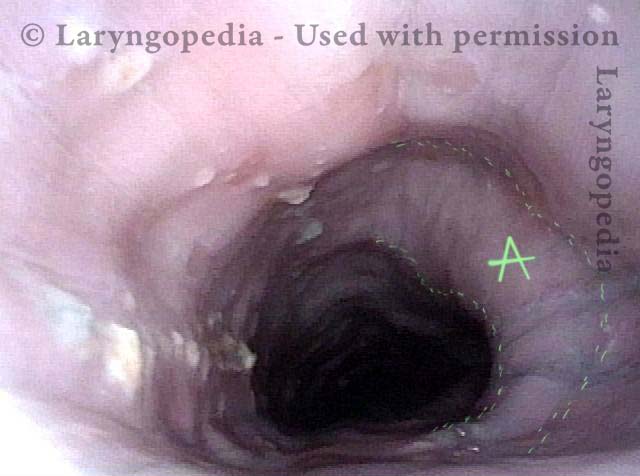

Bronchus is visible (4 of 4)

Bronchus is visible (4 of 4)

The Esophagus Doesn’t Like Being Stretched for Years Due to Untreated R-CPD

Lateral dilation from R-CPD (1 of 3)

Lateral dilation from R-CPD (1 of 3)

Lateral dilation in the upper esophagus (2 of 3)

Lateral dilation in the upper esophagus (2 of 3)

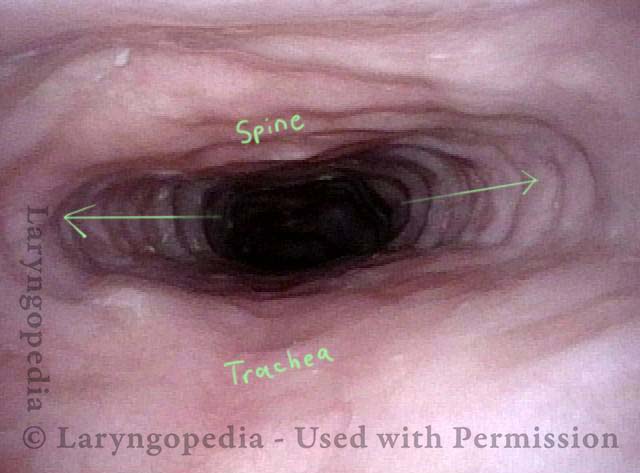

Medial-lateral stretch (3 of 3)

Medial-lateral stretch (3 of 3)

Emerging Esophageal Findings

Aortic shelf (1 of 3)

Aortic shelf (1 of 3)

Bony spur emerges due to stretched esophagus (2 of 3)

Bony spur emerges due to stretched esophagus (2 of 3)

Stretched esophagus due to unburpable air (3 of 3)

Stretched esophagus due to unburpable air (3 of 3)

Example 2

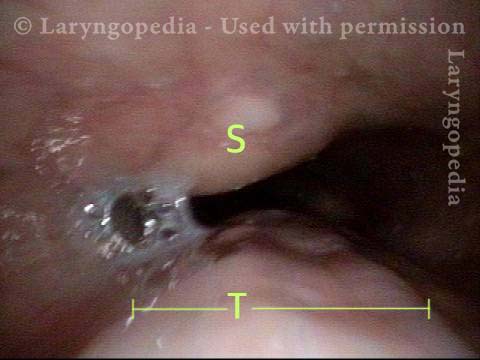

Saliva bubbles (1 of 5)

Saliva bubbles (1 of 5)

Symptoms point to GERD (2 of 5)

Symptoms point to GERD (2 of 5)

Pocket in the aorta (3 of 5)

Pocket in the aorta (3 of 5)

Trapped air expands the esophagus (4 of 5)

Trapped air expands the esophagus (4 of 5)

Exaggerated laterally-stretched esophagus (5 of 5)

Exaggerated laterally-stretched esophagus (5 of 5)

Dramatic Lateral Dilation of the Upper Esophagus

Remarkable lateral dilation (1 of 3)

Remarkable lateral dilation (1 of 3)

Dilated upper esophagus (2 of 3)

Dilated upper esophagus (2 of 3)

Aortic shelf (3 of 3)

Aortic shelf (3 of 3)

Dramatic Dilation of the Esophagus in a Person with R-CPD due to Buildup of Swallowed Air that He Cannot Belch.

View of the mid-esophagus (1 of 2)

View of the mid-esophagus (1 of 2)

View of the mid-esophagus (2 of 2)

View of the mid-esophagus (2 of 2)

R-CPD in X-ray Images

Why do persons with R-CPD experience such daily misery? These X-ray images provide the explanation, as well as the rare “abdominal crisis” in this group is also explained.

In a new video format, Dr. Bastian will discuss various photo essays found across Laryngopedia, and provide in-depth descriptions on their origins and what is going on behind the scenes during the time of capture.