Supraglottic phonation is making voice by means of supraglottic vibration rather than glottic (true vocal cord) vibration. The supraglottic tissues used for vibration can vary between individuals. Vibrating tissue can be the false vocal cords (false cord phonation), aryepiglottic cords, or apical arytenoid mucosa.

Supraglottic phonation may become necessary if the vocal cords are absent or scarred to the point of being unable to vibrate. Examples might include larynx trauma, partial laryngectomy with loss of one or both vocal cords or an inability to bring them close enough together to be entrained into vibration, or progressive radiation damage (radiation fibrosis), usually many years after treatment for cancer.

False Cord Phonation

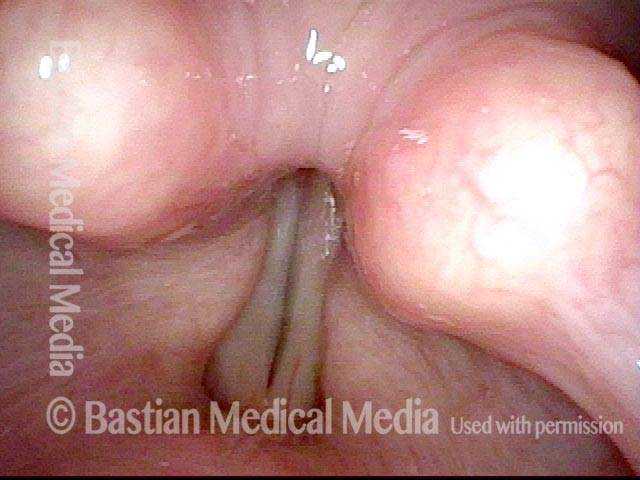

False cord phonation due to flaccid true cords (1 of 5): before false cords begin to vibrate

An elderly man, quiet by nature who uses the voice little, complains of weak, gravelly voice quality. This view of phonation, standard light, shows a slightly wider dark line of phonatory blurring. Also, the false vocal cords are overly approximated, but not yet participating in vibration (for that, see images 4 and 5).

False cord phonation due to flaccid true cords (1 of 5): before false cords begin to vibrate

An elderly man, quiet by nature who uses the voice little, complains of weak, gravelly voice quality. This view of phonation, standard light, shows a slightly wider dark line of phonatory blurring. Also, the false vocal cords are overly approximated, but not yet participating in vibration (for that, see images 4 and 5).

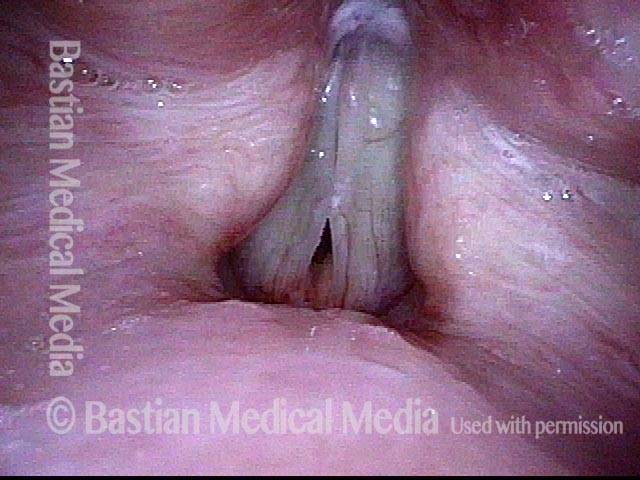

False cord phonation due to flaccid true cords (2 of 5): before false cords begin to vibrate

Strobe light reveals an unusually wide amplitude of vibration, denoting flaccidity of the true vocal cords.

False cord phonation due to flaccid true cords (2 of 5): before false cords begin to vibrate

Strobe light reveals an unusually wide amplitude of vibration, denoting flaccidity of the true vocal cords.

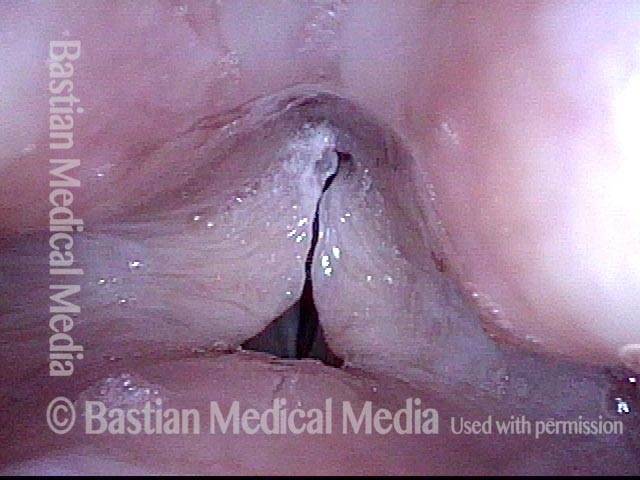

False cord phonation due to flaccid true cords (3 of 5): before false cords begin to vibrate

Maximum closed phase shows the telltale residual opening at the anterior commissure (from this perspective, the lowermost end of the true cords), also a potent indicator of flaccidity.

False cord phonation due to flaccid true cords (3 of 5): before false cords begin to vibrate

Maximum closed phase shows the telltale residual opening at the anterior commissure (from this perspective, the lowermost end of the true cords), also a potent indicator of flaccidity.

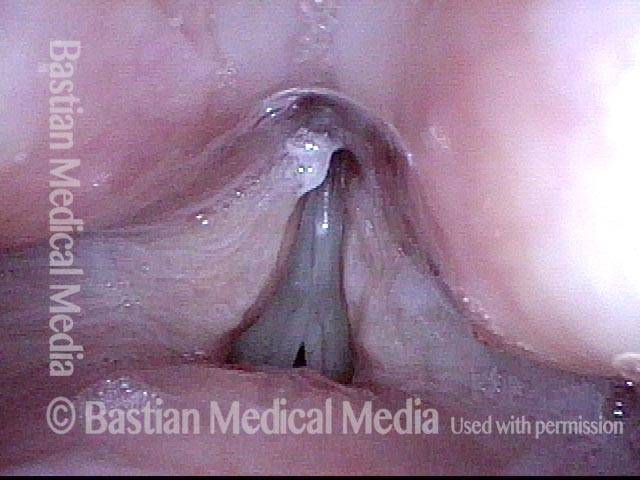

False cord phonation due to flaccid true cords (4 of 5): after false cords begin to vibrate

When asked to produce louder voice, the false cords begin to participate in vibration, and a rough, gravelly superimposed “ godfather” quality arrives. Notice that the true cords are in at least partial open phase of vibration.

False cord phonation due to flaccid true cords (4 of 5): after false cords begin to vibrate

When asked to produce louder voice, the false cords begin to participate in vibration, and a rough, gravelly superimposed “ godfather” quality arrives. Notice that the true cords are in at least partial open phase of vibration.

False cord phonation due to flaccid true cords (5 of 5): after false cords begin to vibrate

Now the false cords are in open phase of vibration, and the true cords are in maximum closed phase of vibration, with the same residual opening anteriorly seen in photo 3. False cord phonation is not to be seen most accurately as primary here, but as a secondary result of effort necessitated by flaccid true cords.

False cord phonation due to flaccid true cords (5 of 5): after false cords begin to vibrate

Now the false cords are in open phase of vibration, and the true cords are in maximum closed phase of vibration, with the same residual opening anteriorly seen in photo 3. False cord phonation is not to be seen most accurately as primary here, but as a secondary result of effort necessitated by flaccid true cords.

Anterior-Posterior Supraglottic / Arytenoid Mucosa Vibration Against the Epiglottis

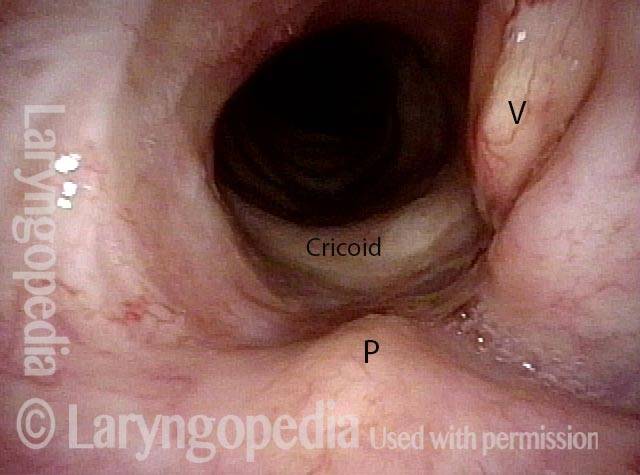

Panoramic view (1 of 4)

Hemilaryngectomy, with standard (unmodified) epiglottic reconstruction. Panoramic view. Right true cord (left of photo) with arytenoid and anterior left true cord have been removed. The right arytenoid mucosa (left of photo) flops anteriorly because the arytenoid cartilage that would lift and stiffen this mucosa is gone on that side. Epiglottis remains in its original position, with petiole (P) opposite asymmetrical arytenoid mounds.

Panoramic view (1 of 4)

Hemilaryngectomy, with standard (unmodified) epiglottic reconstruction. Panoramic view. Right true cord (left of photo) with arytenoid and anterior left true cord have been removed. The right arytenoid mucosa (left of photo) flops anteriorly because the arytenoid cartilage that would lift and stiffen this mucosa is gone on that side. Epiglottis remains in its original position, with petiole (P) opposite asymmetrical arytenoid mounds.

Interior of larynx (2 of 4)

Close up view of interior of larynx during quiet breathing. The vocal process of left arytenoid (right of photo) by "V" and the petiole of the epiglottis by "P". The upper rim of the cricoid is labeled as well.

Interior of larynx (2 of 4)

Close up view of interior of larynx during quiet breathing. The vocal process of left arytenoid (right of photo) by "V" and the petiole of the epiglottis by "P". The upper rim of the cricoid is labeled as well.

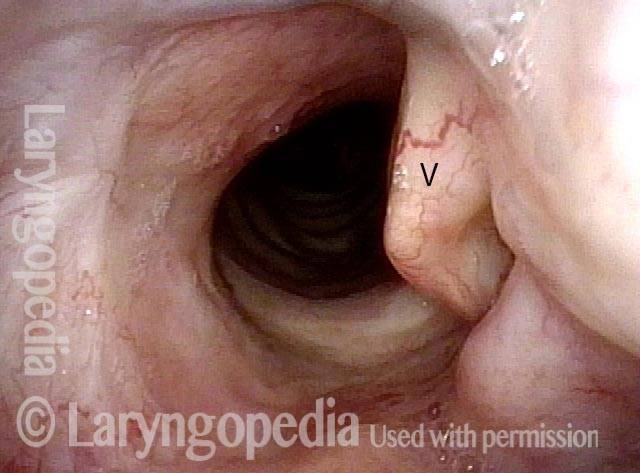

Phonation (3 of 4)

During phonation, the vocal process swings medially but there is nothing at the vocal cord level available to vibrate.

Phonation (3 of 4)

During phonation, the vocal process swings medially but there is nothing at the vocal cord level available to vibrate.

"Wolfman Jack" voice (4 of 4)

Instead, arytenoid and aryepiglottic fold mucosa is pressed into service. These tissues are seen vibrating (blurred) here in order to produce a rough “Wolfman Jack” voice quality. Compare with photo 1.

"Wolfman Jack" voice (4 of 4)

Instead, arytenoid and aryepiglottic fold mucosa is pressed into service. These tissues are seen vibrating (blurred) here in order to produce a rough “Wolfman Jack” voice quality. Compare with photo 1.

Supraglottic Phonation

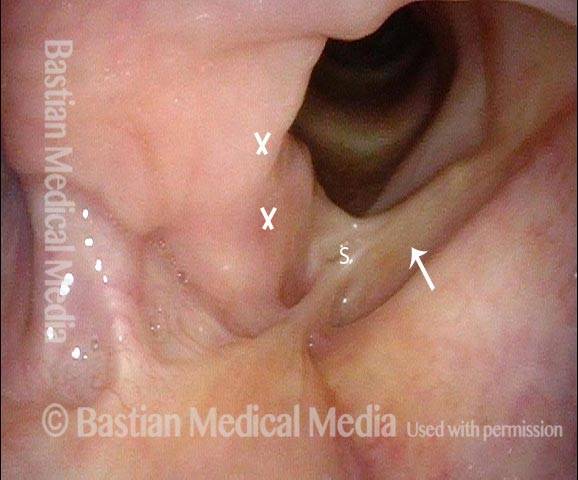

Supraglottic phonation (1 of 6)

After right hemilaryngectomy for cancer, performed elsewhere, breathing position. Notice the left vocal cord (right of image) is partially intact (arrow), though with scarring at its anterior end (at “S”).

Supraglottic phonation (1 of 6)

After right hemilaryngectomy for cancer, performed elsewhere, breathing position. Notice the left vocal cord (right of image) is partially intact (arrow), though with scarring at its anterior end (at “S”).

True vocal cords are blocked (2 of 6)

During supraglottic phonation using conventional view, true vocal cords cannot be seen.

True vocal cords are blocked (2 of 6)

During supraglottic phonation using conventional view, true vocal cords cannot be seen.

Supraglottic phonation (3 of 6)

Under strobe illumination. With assistance of topical anesthesia, during high pitched phonation, is the only “true vocal cord voice” this patient can achieve. This is the “closed” phase of vibration, though of course the glottis is not truly closed as one can see from the persistence of the black glottal gap.

Supraglottic phonation (3 of 6)

Under strobe illumination. With assistance of topical anesthesia, during high pitched phonation, is the only “true vocal cord voice” this patient can achieve. This is the “closed” phase of vibration, though of course the glottis is not truly closed as one can see from the persistence of the black glottal gap.

Breathy voice (4 of 6)

Same view as photo 3, still under strobe illumination, now with left vocal cord slightly lateralized for the “open phase” of vibration. Note that the black glottal gap is slightly wider. This “glottic” or true vocal cord voice is extremely breathy and high-pitched, and will not serve the patient’s vocal needs.

Breathy voice (4 of 6)

Same view as photo 3, still under strobe illumination, now with left vocal cord slightly lateralized for the “open phase” of vibration. Note that the black glottal gap is slightly wider. This “glottic” or true vocal cord voice is extremely breathy and high-pitched, and will not serve the patient’s vocal needs.

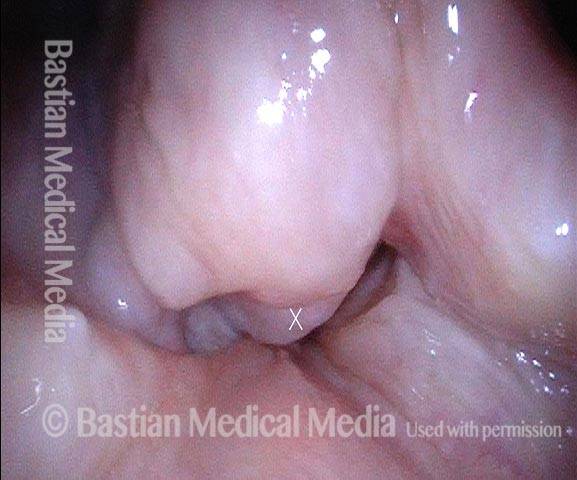

Residual aryepiglottic (5 of 6)

Strobe view during supraglottic phonation, using a much lower pitch and with a rough vocal quality. This is the “closed” phase of vibration with residual aryepiglottic and false cord tissue at "X" partially closing at the level of the intact left false vocal cord.

Residual aryepiglottic (5 of 6)

Strobe view during supraglottic phonation, using a much lower pitch and with a rough vocal quality. This is the “closed” phase of vibration with residual aryepiglottic and false cord tissue at "X" partially closing at the level of the intact left false vocal cord.

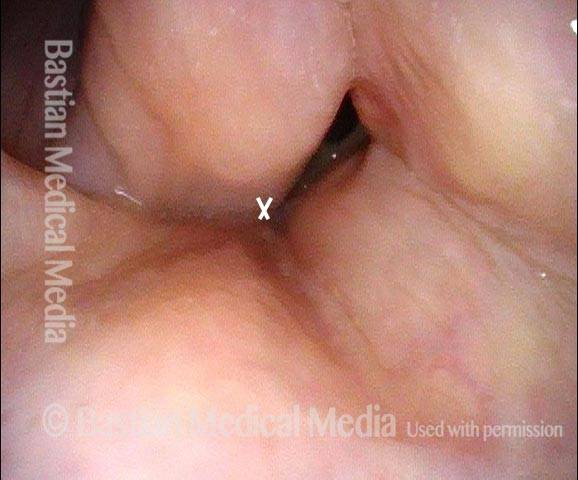

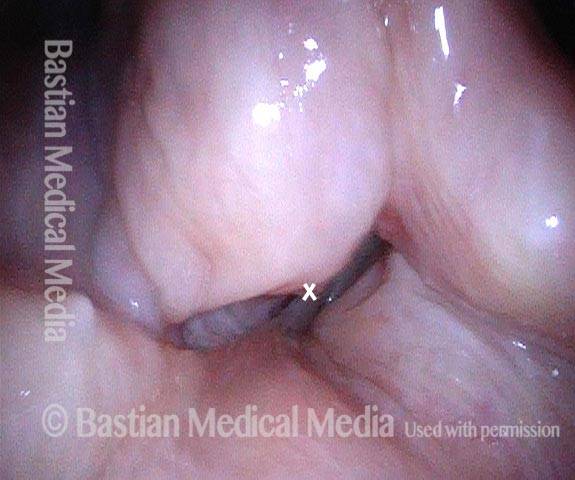

Open phase (6 of 6)

Same view as Photo 5, but at open phase of vibration, with the marked "X" tissue at the “lateral swing” point of vibration.

Open phase (6 of 6)

Same view as Photo 5, but at open phase of vibration, with the marked "X" tissue at the “lateral swing” point of vibration.

Tagged Anatomy & Physiology, Education, Photos