Arytenoid Cartilages

Arytenoid cartilages are a pair of small triangular cartilages in the larynx that help to move the vocal cords. The arytenoid cartilages sit on the upper surface of the cricoid cartilage ring’s posterior section.

Each arytenoid has a body, apex, muscular process, and vocal process. The vocal process is the only part of the arytenoid cartilage that is visible in some of the images found in this post. The vocal process projects into the posterior part of the vocal cord and is covered by thin enough soft tissue (mucosa) covering it that it may “shine through.”

Attachments of the Arytenoid Cartilages

The arytenoid cartilages help to move the vocal cords because the vocal cords are attached to them and because several muscles also attach to the arytenoids and can move them around. The joint capsule (tiny ligaments and fibrous tissue) attaches the arytenoid cartilage to the cricoid cartilage; the vocal cord (comprised mostly of the thyroarytenoid, or TA, muscle) attaches to the arytenoid cartilage at its vocal process.

The PCA and LCA muscles attach to the arytenoid at what is called the muscular process, which points more laterally, at 90 degrees from the vocal process. The interarytenoid muscle (IA) attaches to the arytenoid on the concave posterior surface of each arytenoid’s body; the IA muscle also connects the arytenoids to each other.

Movement of the Arytenoid Cartilages

The IA muscle pulls the arytenoid cartilages together for coughing, voicing, and so forth. The PCA muscles move the arytenoids apart simultaneously to open the larynx widely for breathing. The LCA muscles can move the arytenoids, and especially the vocal processes, toward each other, and can also rock the arytenoids anteriorly.

As the arytenoids move in all these different ways, the vocal cords—being attached to the arytenoids—move along with them. Thus, via the arytenoid cartilages, these muscles cause the vocal cords to separate (abduct) for breathing or come together (adduct) for voicing, throat clearing, coughing, and so forth.

There are also other muscles that affect the vocal cords, but apart from the involvement of the arytenoids: the TA muscle that makes up most of the bulk of each cord can isometrically contract and affect the tension of the cords, for varying the quality and (somewhat) the pitch of the voice, and an external muscle, the cricothyroid, has a major role for creating high pitches.

Arytenoid Mismatch Causing Gravelly Voice Quality Is Hard to Fix in Some Cases of Vocal Cord Paralysis

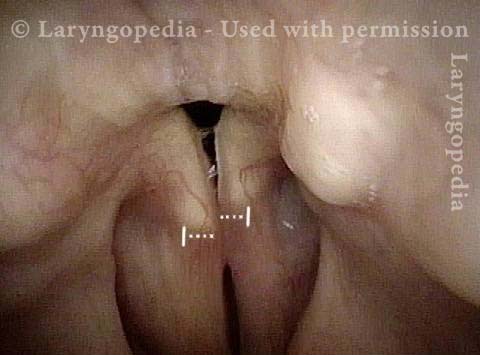

Arytenoids do not align (1 of 5)

Arytenoids do not align (1 of 5)

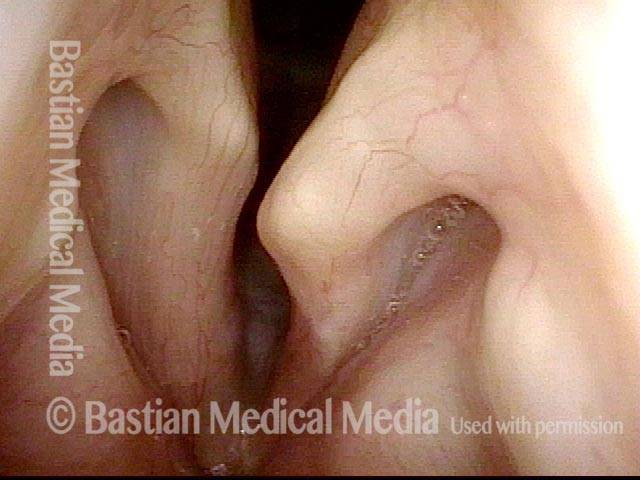

Vocal processes (2 of 5)

Vocal processes (2 of 5)

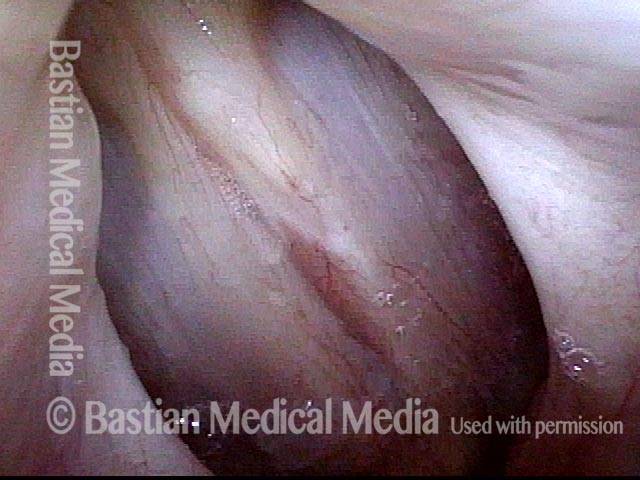

Vocal processes do not match when touching (3 of 5)

Vocal processes do not match when touching (3 of 5)

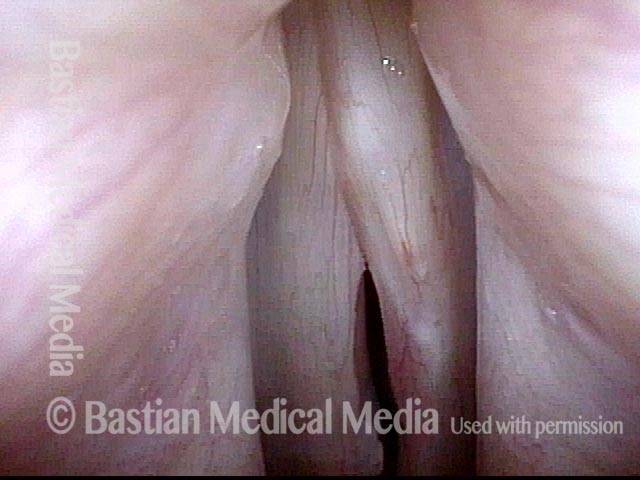

Vocal cords out of alignment (4 of 5)

Vocal cords out of alignment (4 of 5)

Asymmetrical vibration (5 of 5)

Asymmetrical vibration (5 of 5)

What is the Solution?

One could medialize more aggressively posteriorly on the left, hoping to raise the level of the cord, but often attempts to compensate for arytenoid mismatch such as that seen here are only modestly successful. Arytenoid superstructure is not useful for assessment of match; instead, the examiner should judge match at the vocal processes.