Medialization Laryngoplasty

Medialization laryngoplasty is a surgical procedure performed to push a paralyzed, atrophied, or scarred vocal cord toward the other vocal cord and reduce flaccidity. It is typically performed under sedation and local (not general) anesthesia, on an outpatient basis.

Patient with Vocal Cord Paralysis, BEFORE Medialization Laryngoplasty

Same patient, one week AFTER medialization laryngoplasty

Medialization, Before and After

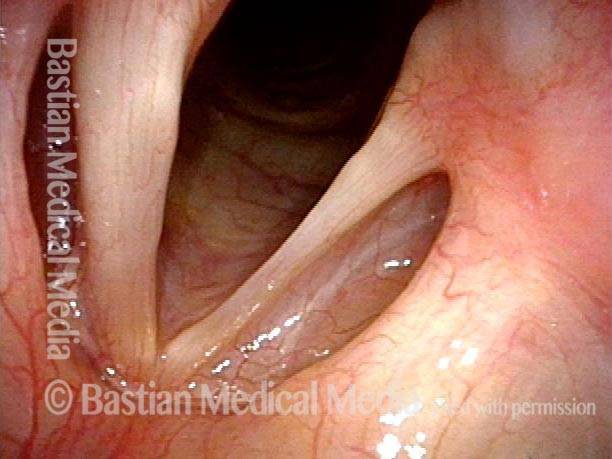

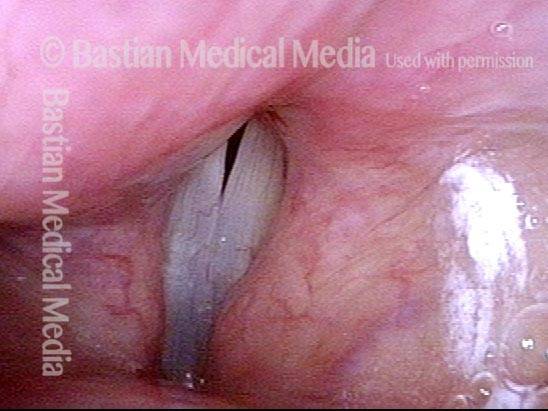

Medialization: before (1 of 7)

TA + LCA paresis of the left vocal cord (right of photo). Vocal cords in breathing position. The evidence of TA muscle weakness includes: convex margin; capacious ventricle; prominence of vocal process; and “sphaghetti-linguini” difference between the cords. It appears that the PCA muscle is working, as the left cord is quite lateralized. The LCA muscle is not fully evaluated until the patient phonates (next photo).

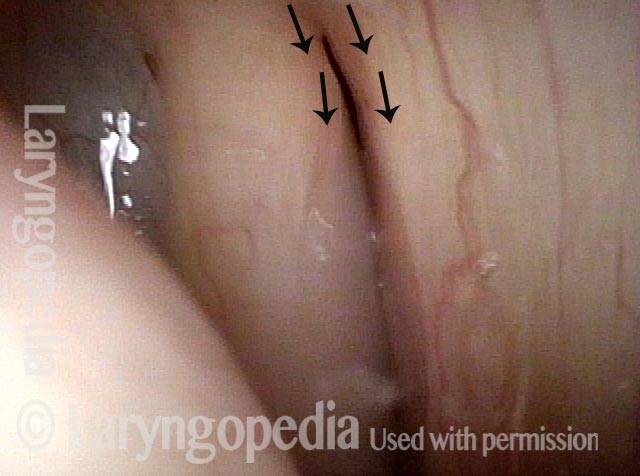

Medialization: before (1 of 7)

TA + LCA paresis of the left vocal cord (right of photo). Vocal cords in breathing position. The evidence of TA muscle weakness includes: convex margin; capacious ventricle; prominence of vocal process; and “sphaghetti-linguini” difference between the cords. It appears that the PCA muscle is working, as the left cord is quite lateralized. The LCA muscle is not fully evaluated until the patient phonates (next photo).

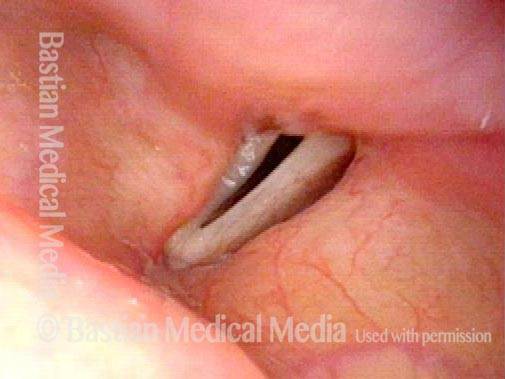

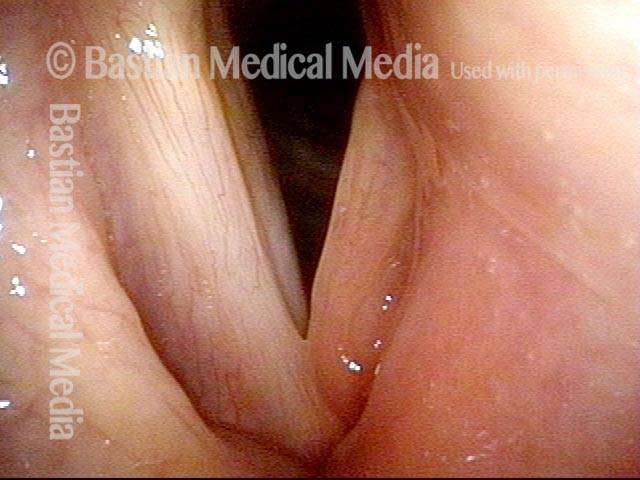

Medialization: before (2 of 7)

Phonation. Notice the lateral buckling of the membranous cord, indicative of TA weakness. In addition, notice the lateral turning of the vocal process (arrow), indicative of LCA weakness. For more on observing LCA weakness, see also our LCA-only paresis entry.

Medialization: before (2 of 7)

Phonation. Notice the lateral buckling of the membranous cord, indicative of TA weakness. In addition, notice the lateral turning of the vocal process (arrow), indicative of LCA weakness. For more on observing LCA weakness, see also our LCA-only paresis entry.

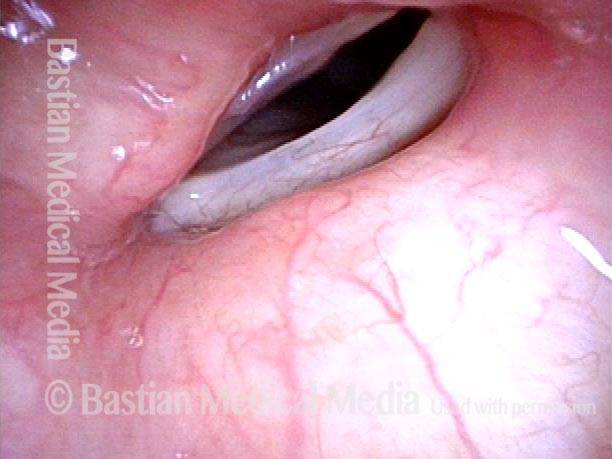

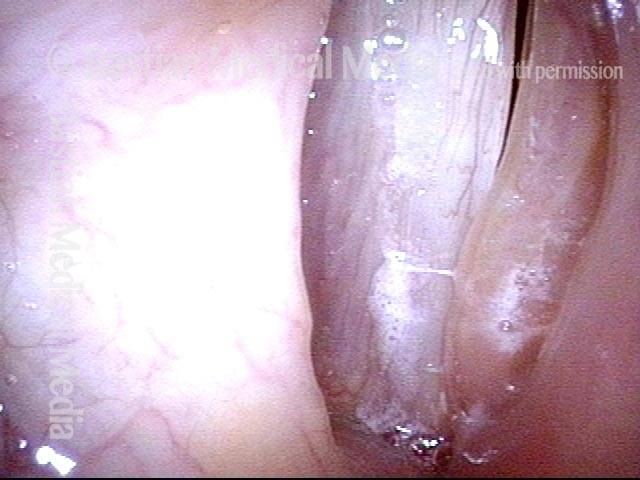

Medialization: 2 weeks after (3 of 7)

Two weeks after medialization of the left vocal cord (right of photo). There is expected inflammation and resolving bruising. The vocal cord is appropriately filled out. Voice is already dramatically improved.

Medialization: 2 weeks after (3 of 7)

Two weeks after medialization of the left vocal cord (right of photo). There is expected inflammation and resolving bruising. The vocal cord is appropriately filled out. Voice is already dramatically improved.

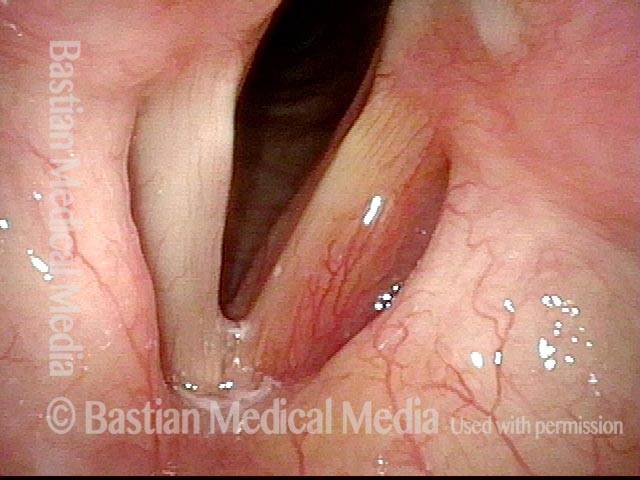

Medialization: 2 weeks after (4 of 7)

Phonation. This view shows marked reduction of the gap, explaining why the voice is now strong, and no longer breathy.

Medialization: 2 weeks after (4 of 7)

Phonation. This view shows marked reduction of the gap, explaining why the voice is now strong, and no longer breathy.

Medialization: 3 months after (5 of 7)

A few months later. The implanted left vocal cord (right of image) remains plumped up, and is at the midline. The right cord abducts normally.

Medialization: 3 months after (5 of 7)

A few months later. The implanted left vocal cord (right of image) remains plumped up, and is at the midline. The right cord abducts normally.

Medialization: 3 months after (6 of 7)

Phonation, under strobe light. There is good vocal cord approximation, which explains the patient’s much improved voice. Note that the view here and in photo 7 is rotated at least 30 degrees counter-clockwise relative to photo 5 (see the false cord line, for reference), possibly giving the illusion that the implanted, paretic cord (right of image) is moving to close the gap, when in the fact the opposite cord is.

Medialization: 3 months after (6 of 7)

Phonation, under strobe light. There is good vocal cord approximation, which explains the patient’s much improved voice. Note that the view here and in photo 7 is rotated at least 30 degrees counter-clockwise relative to photo 5 (see the false cord line, for reference), possibly giving the illusion that the implanted, paretic cord (right of image) is moving to close the gap, when in the fact the opposite cord is.

Medialization: 3 months after (7 of 7)

Phonation, open phase of vibration, under strobe light. This view shows that the implanted cord has better bulk and firmness than the un-implanted cord. Mucosal wave is greater in the un-implanted cord. Occasionally, a mobile but somewhat flaccid cord, such as seen here, if associated with weak voice leads to placement of a second implant into the mobile cord. In this case, the patient is content with his voice.

Medialization: 3 months after (7 of 7)

Phonation, open phase of vibration, under strobe light. This view shows that the implanted cord has better bulk and firmness than the un-implanted cord. Mucosal wave is greater in the un-implanted cord. Occasionally, a mobile but somewhat flaccid cord, such as seen here, if associated with weak voice leads to placement of a second implant into the mobile cord. In this case, the patient is content with his voice.

Example 2

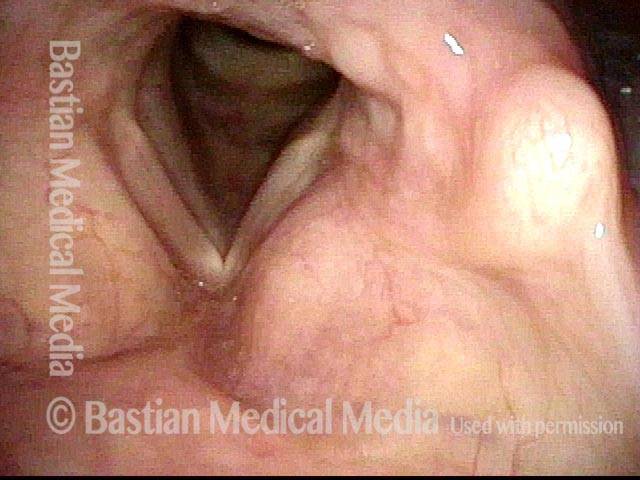

Before medialization (1 of 4)

Right vocal cord (left of photo) paralysis. During breathing as shown here, the right cord (left of photo) is paramedian, while the left cord (right of photo) is widely abducted. Note also the bowing (curvature) of the right cord (left of photo), and the prominent ventricle, both of which are indications of atrophy/ reduced bulk of the muscle within that cord.

Before medialization (1 of 4)

Right vocal cord (left of photo) paralysis. During breathing as shown here, the right cord (left of photo) is paramedian, while the left cord (right of photo) is widely abducted. Note also the bowing (curvature) of the right cord (left of photo), and the prominent ventricle, both of which are indications of atrophy/ reduced bulk of the muscle within that cord.

Before medialization (2 of 4)

Phonation, with vibratory blurring under standard light. Right cord (left of photo) remains paramedian, and the left cord (right of photo) has swung to the midline. Even so, large gap between the cords shows that closure is incomplete, and this explains the weak, air-wasting voice; the patient can only say a few words before running out of air and having to take another breath.

Before medialization (2 of 4)

Phonation, with vibratory blurring under standard light. Right cord (left of photo) remains paramedian, and the left cord (right of photo) has swung to the midline. Even so, large gap between the cords shows that closure is incomplete, and this explains the weak, air-wasting voice; the patient can only say a few words before running out of air and having to take another breath.

After medialization (3 of 4)

After medialization and placement of a silastic implant, the right cord (left of photo) is less atrophied and the bowing much diminished. The cord has also been shifted slightly to the midline.

After medialization (3 of 4)

After medialization and placement of a silastic implant, the right cord (left of photo) is less atrophied and the bowing much diminished. The cord has also been shifted slightly to the midline.

After medialization (4 of 4)

Phonation, again with vibratory blurring, but notice the much better approximation of the cords. The voice is stronger, and less air-wasting.

After medialization (4 of 4)

Phonation, again with vibratory blurring, but notice the much better approximation of the cords. The voice is stronger, and less air-wasting.

Vocal Cord Paralysis, Before and After Medialization

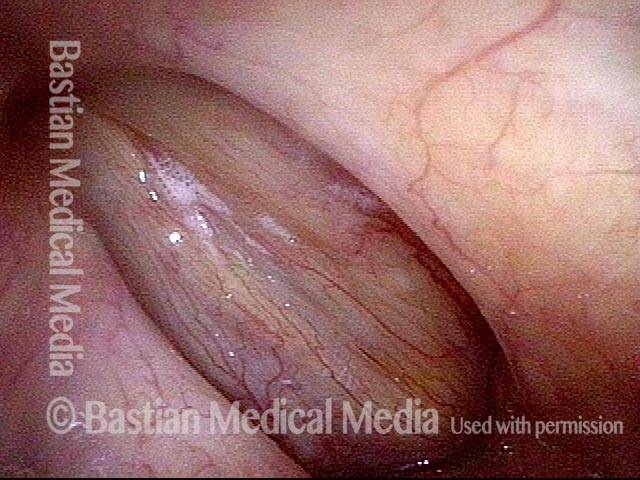

Vocal cord paralysis: before medialization (1 of 12)

A classic example of “spaghetti-linguine” vocal cords, here in breathing position. The “linguine” cord (left of image) is normal; the “spaghetti” cord (right of image) is paralyzed, likely since birth. On the paralyzed side, notice the deep and broad ventricle, mild bowing of the margin of the cord, and reduced width of the upper surface of the cord (“spaghetti”-like), as compared with the non-paralyzed side.

Vocal cord paralysis: before medialization (1 of 12)

A classic example of “spaghetti-linguine” vocal cords, here in breathing position. The “linguine” cord (left of image) is normal; the “spaghetti” cord (right of image) is paralyzed, likely since birth. On the paralyzed side, notice the deep and broad ventricle, mild bowing of the margin of the cord, and reduced width of the upper surface of the cord (“spaghetti”-like), as compared with the non-paralyzed side.

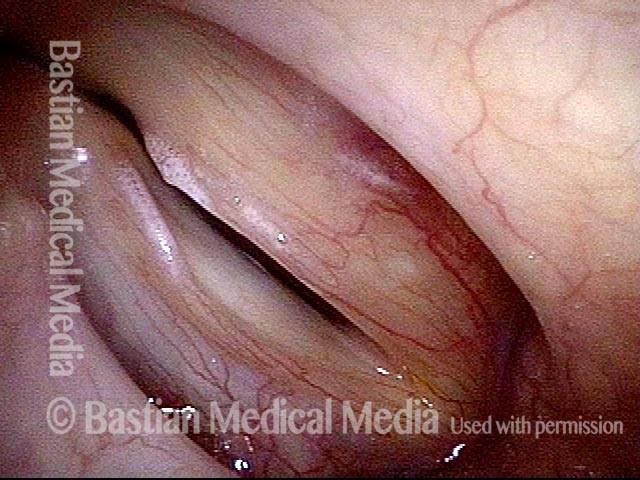

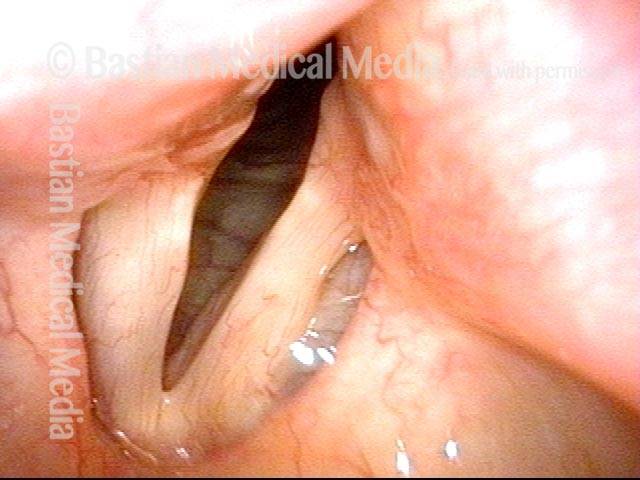

Vocal cord paralysis: before medialization (2 of 12)

Phonation, more distant view, under standard light. Notice the considerable gap between the vocal cords. This gap correlates with the patient’s weak and air-wasting voice quality.

Vocal cord paralysis: before medialization (2 of 12)

Phonation, more distant view, under standard light. Notice the considerable gap between the vocal cords. This gap correlates with the patient’s weak and air-wasting voice quality.

Increased amplitude + bowing (3 of 12)

Open phase of vibration, under strobe light. The paralyzed cord (right of image) has a much increased amplitude (lateral or outward excursion) and exaggerated bowing, due to its flaccidity.

Increased amplitude + bowing (3 of 12)

Open phase of vibration, under strobe light. The paralyzed cord (right of image) has a much increased amplitude (lateral or outward excursion) and exaggerated bowing, due to its flaccidity.

Paralyzed cord cannot close (4 of 12)

“Closed” phase of vibration, which is of course not closed at all, because the paralyzed cord (right of image) cannot come fully to the midline.

Paralyzed cord cannot close (4 of 12)

“Closed” phase of vibration, which is of course not closed at all, because the paralyzed cord (right of image) cannot come fully to the midline.

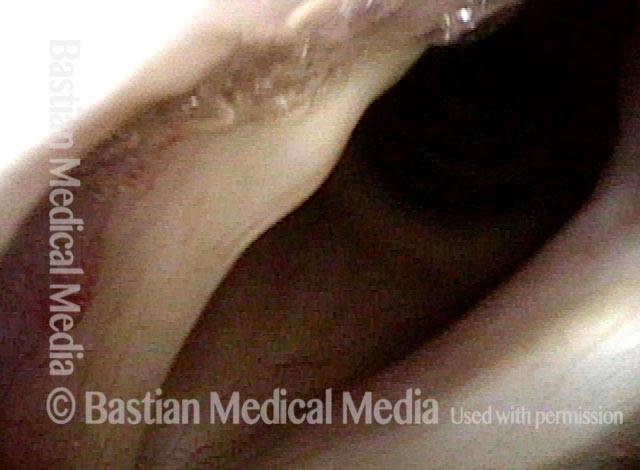

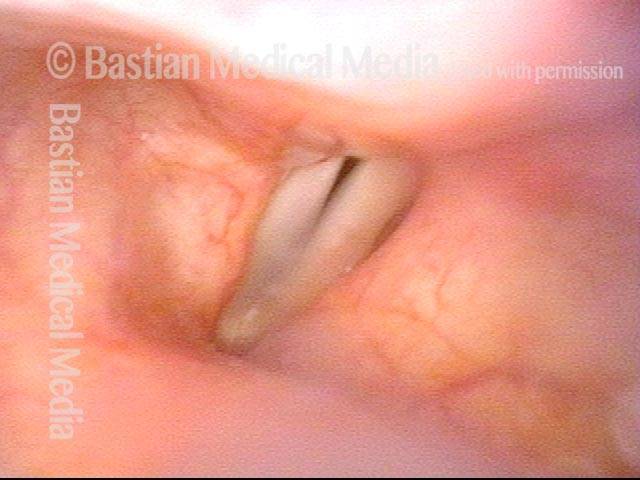

Visual symptoms are diminished (5 of 12)

One week after surgical medialization of the paralyzed cord (right of image), using a silastic implant buried deeply within the cord. Notice that the ventricle is no longer capacious, and the free margin is no longer bowed. Furthermore, in contrast with photo 1 of this series, the “spaghetti-linguine” description of these vocal cords is no longer apt.

Visual symptoms are diminished (5 of 12)

One week after surgical medialization of the paralyzed cord (right of image), using a silastic implant buried deeply within the cord. Notice that the ventricle is no longer capacious, and the free margin is no longer bowed. Furthermore, in contrast with photo 1 of this series, the “spaghetti-linguine” description of these vocal cords is no longer apt.

Gap is gone (6 of 12)

Phonation, under standard light. The gap between the cords is no longer seen (compare with photo 2), and the patient’s spontaneous speaking voice sounds normal. She can recruit loudness effectively without any luffing or observable weakness.

Gap is gone (6 of 12)

Phonation, under standard light. The gap between the cords is no longer seen (compare with photo 2), and the patient’s spontaneous speaking voice sounds normal. She can recruit loudness effectively without any luffing or observable weakness.

Similar lateral excursion (7 of 12)

Open phase of vibration, under strobe light. The lateral or outward excursion of the paralyzed cord (right of image) is now similar to that of the non-paralyzed cord. Compare with photo 3.

Similar lateral excursion (7 of 12)

Open phase of vibration, under strobe light. The lateral or outward excursion of the paralyzed cord (right of image) is now similar to that of the non-paralyzed cord. Compare with photo 3.

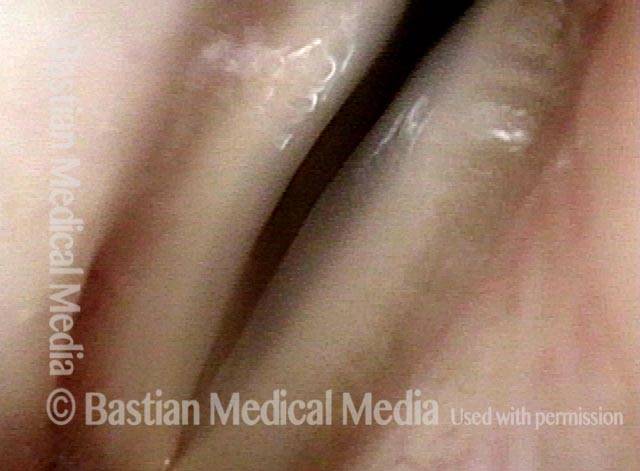

Closed phase is improved (8 of 12)

The closed phase of vibration is much more closed than preoperatively. Compare with photo 4.

Closed phase is improved (8 of 12)

The closed phase of vibration is much more closed than preoperatively. Compare with photo 4.

5 months after medialization (9 of 12)

Five months after medialization. Compare this partially abducted position with photos 1 and 5 of this series.

5 months after medialization (9 of 12)

Five months after medialization. Compare this partially abducted position with photos 1 and 5 of this series.

5 months after medialization (10 of 12)

Phonation, under standard light, showing vibratory blur. Compare with photos 2 and 6 of this series.

5 months after medialization (10 of 12)

Phonation, under standard light, showing vibratory blur. Compare with photos 2 and 6 of this series.

5 months after medialization (11 of 12)

Open phase of vibration, under strobe light. As in photo 7 of this series, and in contrast to photo 3, the implant does not permit the paralyzed cord (right of image) to “buckle” laterally, or outward. If anything, the vibratory excursion of the non-paralyzed (and un-implanted) cord is greater than that of the paralyzed, implanted cord.

5 months after medialization (11 of 12)

Open phase of vibration, under strobe light. As in photo 7 of this series, and in contrast to photo 3, the implant does not permit the paralyzed cord (right of image) to “buckle” laterally, or outward. If anything, the vibratory excursion of the non-paralyzed (and un-implanted) cord is greater than that of the paralyzed, implanted cord.

5 months after medialization (12 of 12)

The closed phase of vibration is now virtually normal, similar to photo 8 and in contrast with photo 4.

5 months after medialization (12 of 12)

The closed phase of vibration is now virtually normal, similar to photo 8 and in contrast with photo 4.

Extrusion of Vocal Cord Implant

Inflamed left cord (1 of 3)

Patient with a paralyzed left vocal cord (right of image), who several years ago had successful medialization of that cord with a silastic wedge. More recently, several months ago, she noticed pain and swelling during some intense aerobic activity and then a persistently roughened voice quality. This view shows that the left cord is inflamed.

Inflamed left cord (1 of 3)

Patient with a paralyzed left vocal cord (right of image), who several years ago had successful medialization of that cord with a silastic wedge. More recently, several months ago, she noticed pain and swelling during some intense aerobic activity and then a persistently roughened voice quality. This view shows that the left cord is inflamed.

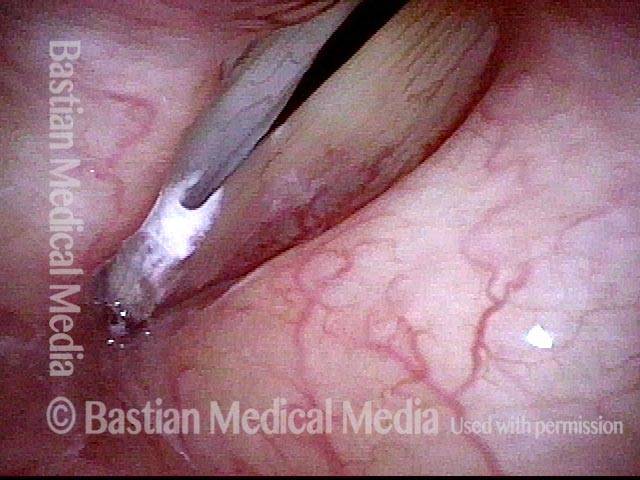

Extrusion of vocal cord implant (2 of 3)

Strobe lighting. Note the convex shape of the left cord’s anterior end (the lower end, in this photo). This convexity is not caused by over-medialization, but instead by the inflammatory reaction.

Extrusion of vocal cord implant (2 of 3)

Strobe lighting. Note the convex shape of the left cord’s anterior end (the lower end, in this photo). This convexity is not caused by over-medialization, but instead by the inflammatory reaction.

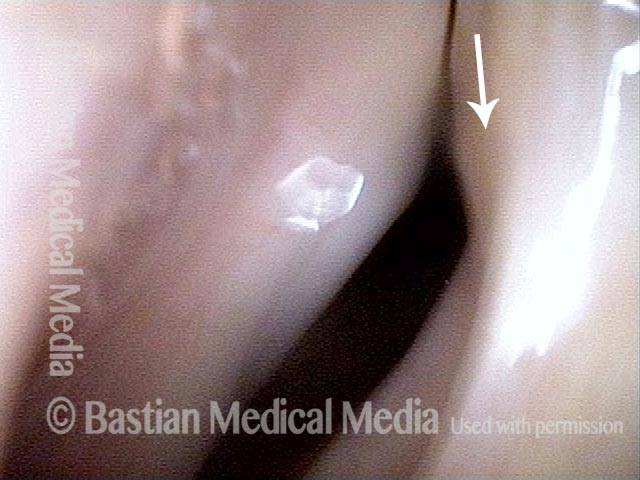

Exposed Implant (3 of 3)

Closer view shows that the problem is exposure of the silastic implant. The actual silastic is bare at the arrow. Whitish exudate covers the remaining exposed implant. This is a rare event after medialization with a silastic implant.

Exposed Implant (3 of 3)

Closer view shows that the problem is exposure of the silastic implant. The actual silastic is bare at the arrow. Whitish exudate covers the remaining exposed implant. This is a rare event after medialization with a silastic implant.

Paresis, TA + LCA, Before and After Medialization

Paresis, TA + LCA (1 of 7)

This patient has idiopathic right TA + LCA paresis. From a distant view, the unopposed pull of the right PCA (left of photo) can already be detected, but is better seen in the next photo.

Paresis, TA + LCA (1 of 7)

This patient has idiopathic right TA + LCA paresis. From a distant view, the unopposed pull of the right PCA (left of photo) can already be detected, but is better seen in the next photo.

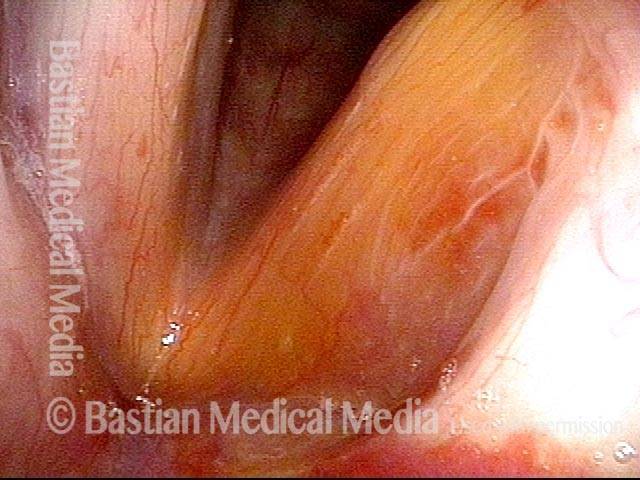

Paresis, TA + LCA (2 of 7)

At closer range and in a breathing position, both PCA muscles work to fully lateralize the cords. The right (left of photo, in red) TA paralysis/atrophy is seen via a spaghetti-linguini difference in the cords and a larger, deeper right ventricle. Most notably, the right vocal process pulls laterally because the paralyzed LCA does not resist unopposed pull of the active PCA.

Paresis, TA + LCA (2 of 7)

At closer range and in a breathing position, both PCA muscles work to fully lateralize the cords. The right (left of photo, in red) TA paralysis/atrophy is seen via a spaghetti-linguini difference in the cords and a larger, deeper right ventricle. Most notably, the right vocal process pulls laterally because the paralyzed LCA does not resist unopposed pull of the active PCA.

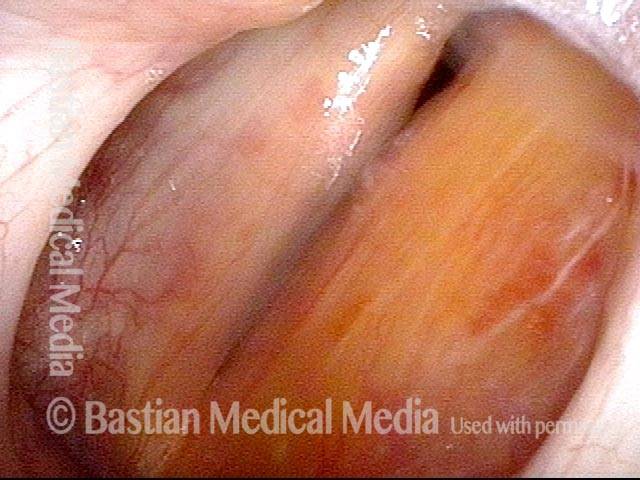

Paresis, TA + LCA (3 of 7)

Beginning to approach phonation position, the cords begin to move to the midline via function of the IA muscles, and the left cord (right of photo) reaches the midline via function of the left LCA muscle. Absent function of the right LCA and TA (left of photo) continues to be seen clearly in this view.

Paresis, TA + LCA (3 of 7)

Beginning to approach phonation position, the cords begin to move to the midline via function of the IA muscles, and the left cord (right of photo) reaches the midline via function of the left LCA muscle. Absent function of the right LCA and TA (left of photo) continues to be seen clearly in this view.

Paresis, TA + LCA (4 of 7)

During phonation, vibratory blur is seen under standard light, and lateral buckling of the flaccid right cord (left of photo).

Paresis, TA + LCA (4 of 7)

During phonation, vibratory blur is seen under standard light, and lateral buckling of the flaccid right cord (left of photo).

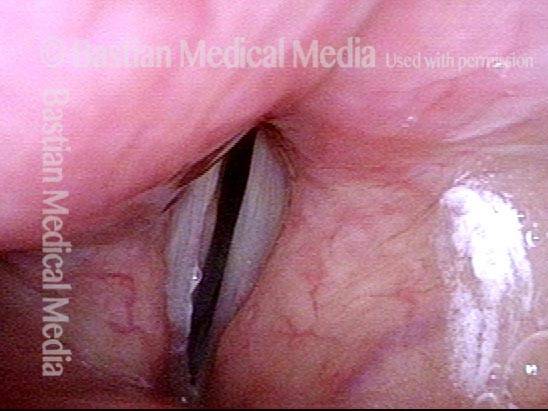

Paresis, TA + LCA: after medialization (5 of 7)

Soon after a simple medialization of right cord (left of photo) with a silastic wedge, resulting in the plumpness of the right cord. Compare with photos 1 and 2.

Paresis, TA + LCA: after medialization (5 of 7)

Soon after a simple medialization of right cord (left of photo) with a silastic wedge, resulting in the plumpness of the right cord. Compare with photos 1 and 2.

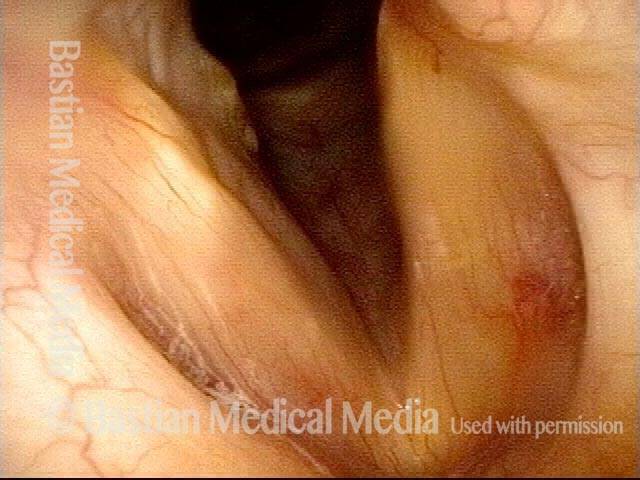

Paresis, TA + LCA: after medialization (6 of 7)

Again beginning to approach phonation position. See again the plumpness of the right cord (left of photo). Compare with photo 3.

Paresis, TA + LCA: after medialization (6 of 7)

Again beginning to approach phonation position. See again the plumpness of the right cord (left of photo). Compare with photo 3.

Paresis, TA + LCA: after medialization (7 of 7)

During phonation, there is much better contact between the cords, and the right cord (left of photo) is no longer flaccid. Compare with photo 4.

Paresis, TA + LCA: after medialization (7 of 7)

During phonation, there is much better contact between the cords, and the right cord (left of photo) is no longer flaccid. Compare with photo 4.

Medialization Laryngoplasty Typically Doesn’t Fix the LCA “Finding.”

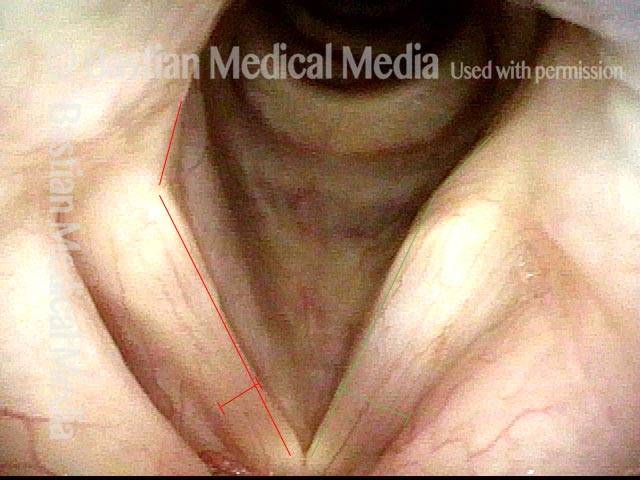

Left vocal cord paralysis (1 of 4)

Many years after treatment for lung cancer, this man’s voice has abruptly weakened. Here we see left vocal cord paralysis (right of photo). The most striking finding (of several) in this view is the margin bowing of the left cord (compare dotted lines, right of photo).

Left vocal cord paralysis (1 of 4)

Many years after treatment for lung cancer, this man’s voice has abruptly weakened. Here we see left vocal cord paralysis (right of photo). The most striking finding (of several) in this view is the margin bowing of the left cord (compare dotted lines, right of photo).

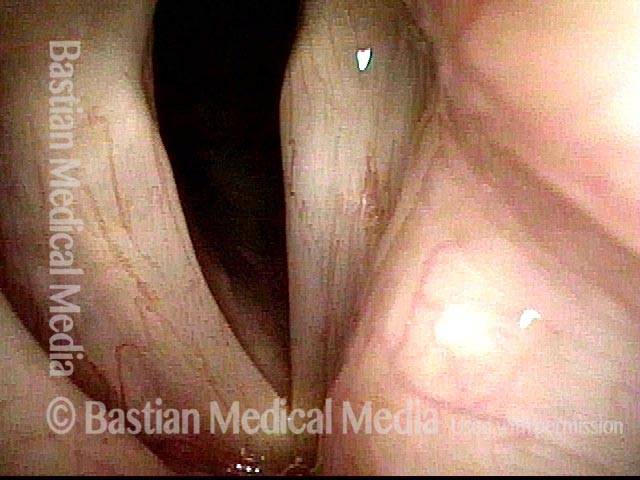

Bowing during phonation (2 of 4)

During phonation, the right vocal process (left of photo) turns medially due to intact LCA; on the left (right of photo), with LCA paralyzed, the vocal process turns laterally (compare posterior arrows).

Bowing during phonation (2 of 4)

During phonation, the right vocal process (left of photo) turns medially due to intact LCA; on the left (right of photo), with LCA paralyzed, the vocal process turns laterally (compare posterior arrows).

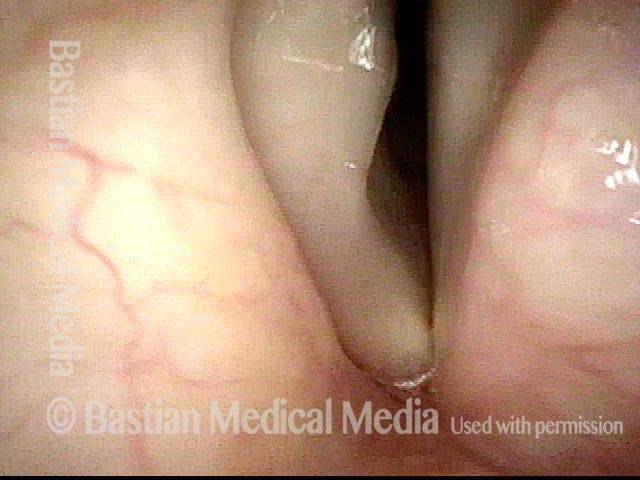

After medialization (3 of 4)

A few months after medialization (an implant placed deep inside the left vocal cord), the left vocal cord margin is now straight rather than bowed (compare with photo 1).

After medialization (3 of 4)

A few months after medialization (an implant placed deep inside the left vocal cord), the left vocal cord margin is now straight rather than bowed (compare with photo 1).

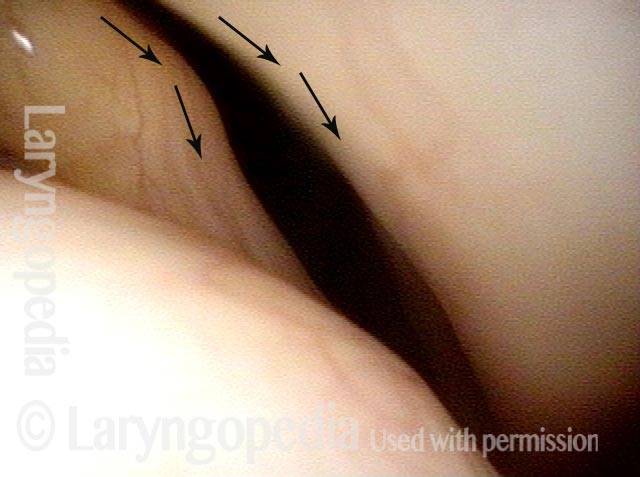

Lateral turning remains unchanged (4 of 4)

During phonation, a striking change is the diminished gap between the cords, and this explains his much stronger voice. The lateral turning of the left vocal process (right of photo) is still seen, however. Medialization tends to “fix” the flaccidity and lateralization of the paralyzed vocal cord, and to reduce the gap between the cord. Compare with photo 2. As seen here, the lateral turning of the vocal process is still seen to some degree. If the voice were not so good and satisfying to the patient, this visual finding would be an argument for arytenoid adduction.

Lateral turning remains unchanged (4 of 4)

During phonation, a striking change is the diminished gap between the cords, and this explains his much stronger voice. The lateral turning of the left vocal process (right of photo) is still seen, however. Medialization tends to “fix” the flaccidity and lateralization of the paralyzed vocal cord, and to reduce the gap between the cord. Compare with photo 2. As seen here, the lateral turning of the vocal process is still seen to some degree. If the voice were not so good and satisfying to the patient, this visual finding would be an argument for arytenoid adduction.

Share this article

Injection Medialization for Vocal Cord Paresis

See an example of one variant of vocal cord paresis and how it limits the voice. Then watch a medialization procedure in which voice gel is injected into the vocal cord affected by paresis, and hear how the voice thereafter improves.

Table of Contents

Tagged Audio, Photos, Treatment, Videos, Voice & other larynx disorders