Retrograde Cricopharyngeus Dysfunction (R-CPD)

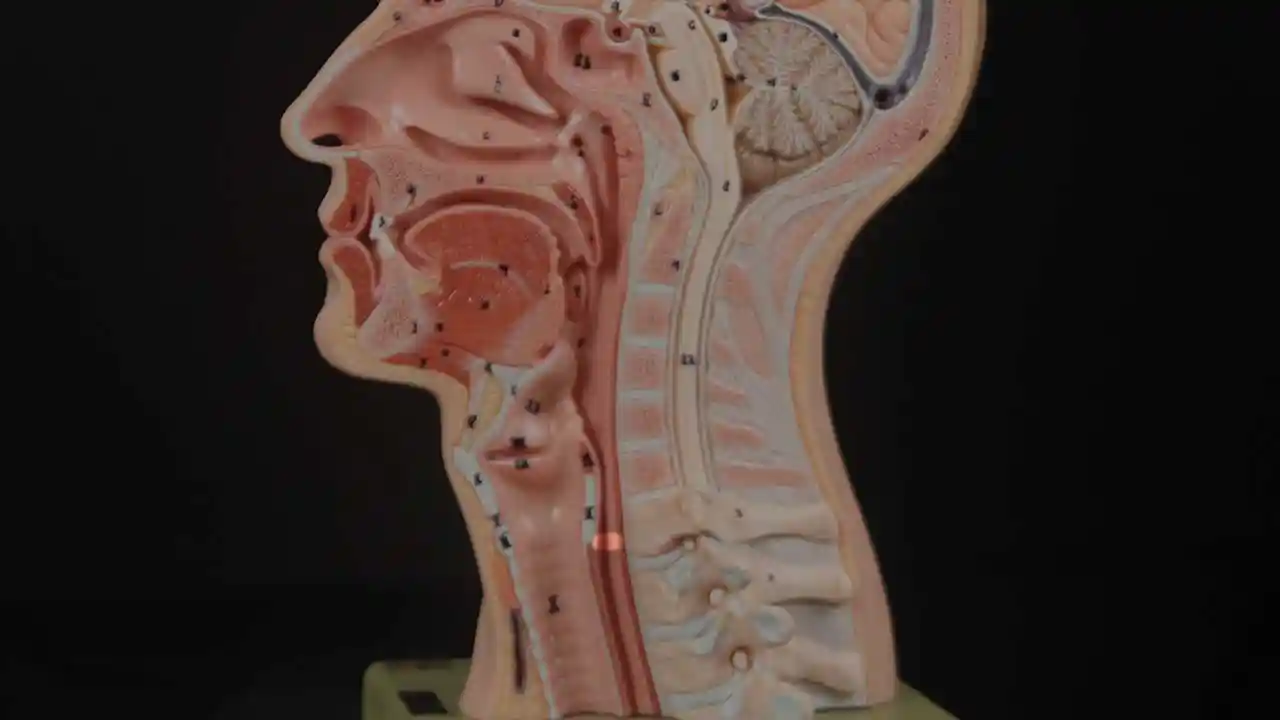

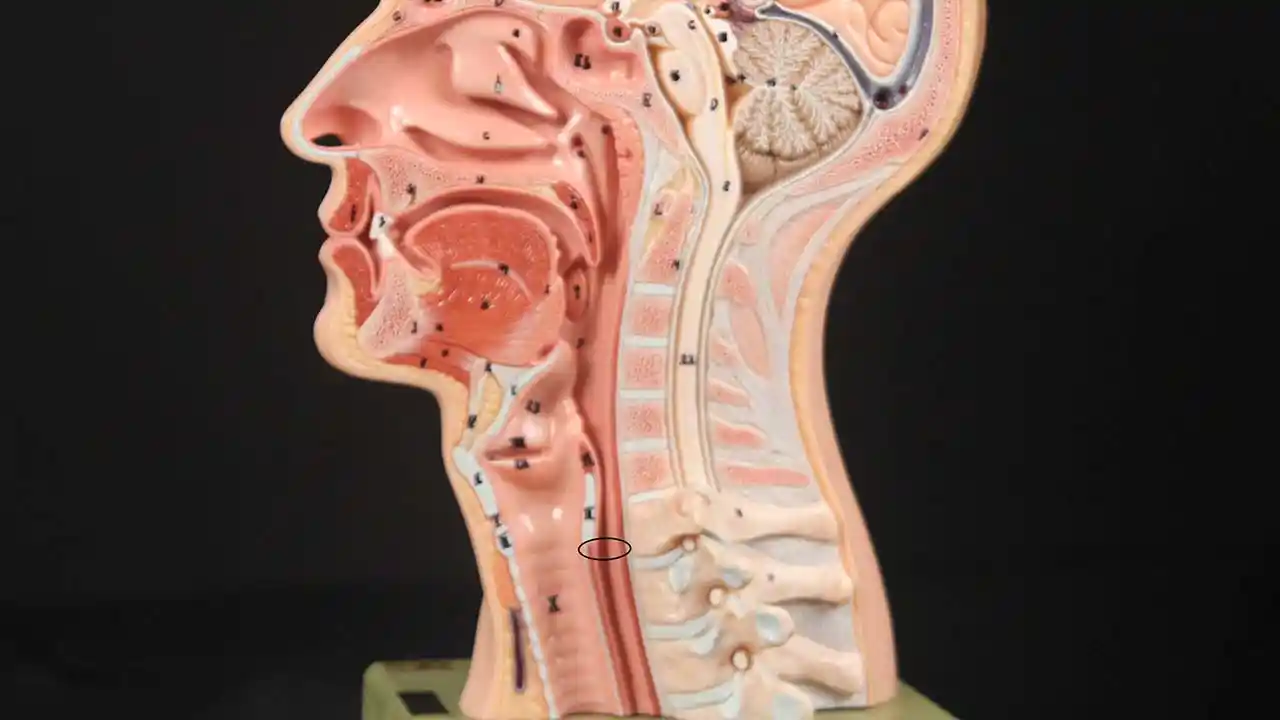

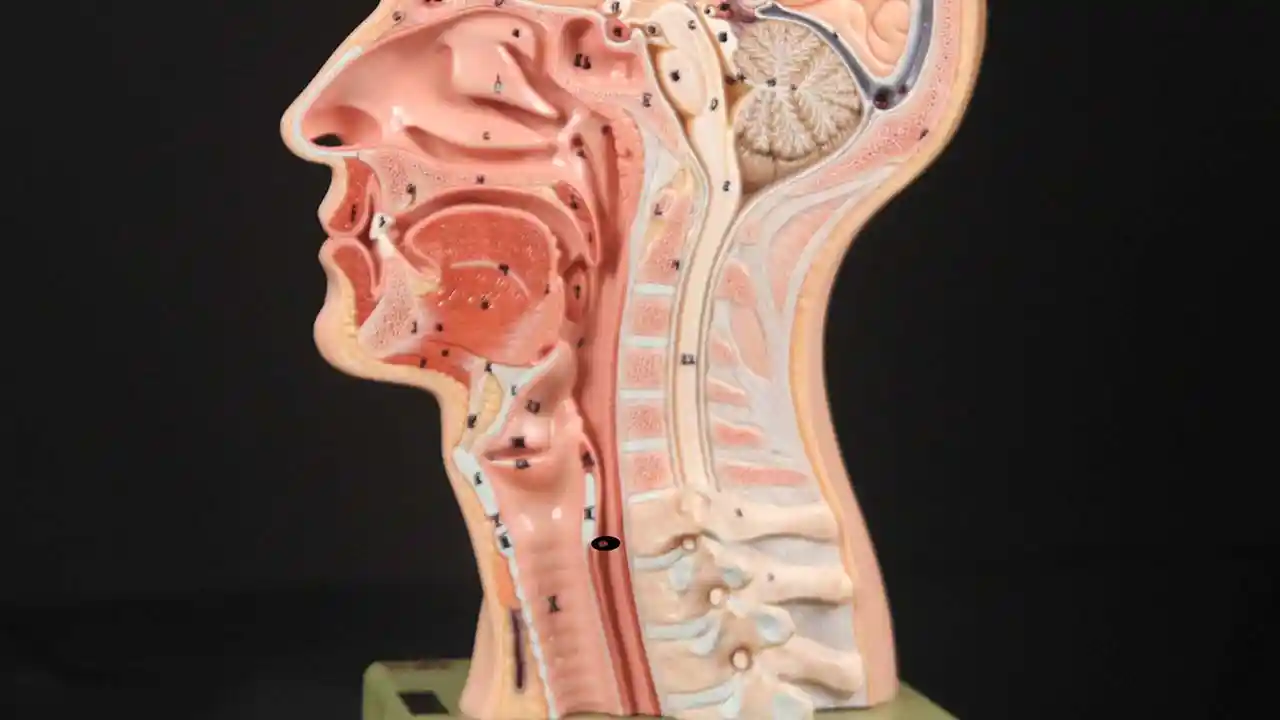

Inability to belch or “burp” (Also known as Retrograde Cricopharyngeus Dysfunction, or R-CPD for short) occurs when the upper esophageal sphincter (cricopharyngeus muscle) loses its ability to relax in order to release the “bubble” of air. The sphincter is a muscular valve that encircles the upper end of the esophagus just below the lower end of the throat passage. If looking from the front at a person’s neck, it is just below the “Adam’s / Eve’s apple” and more specifically, directly behind the cricoid cartilage.

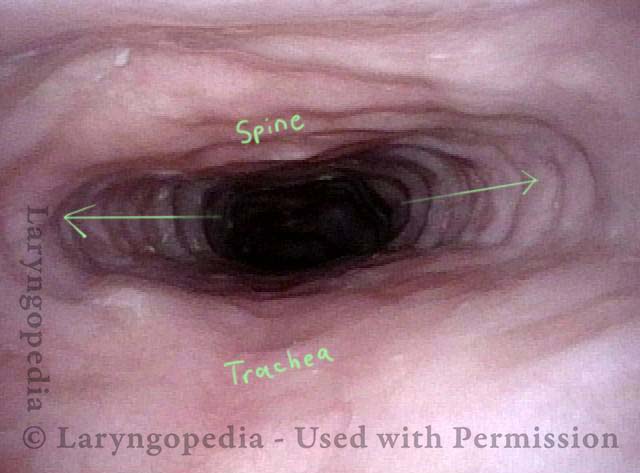

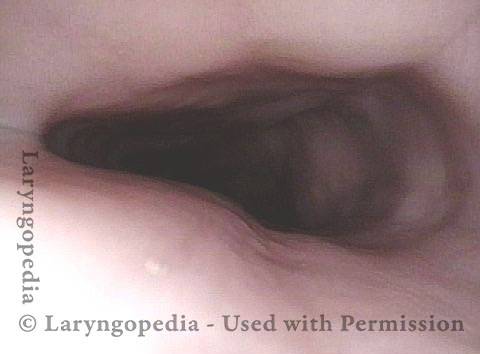

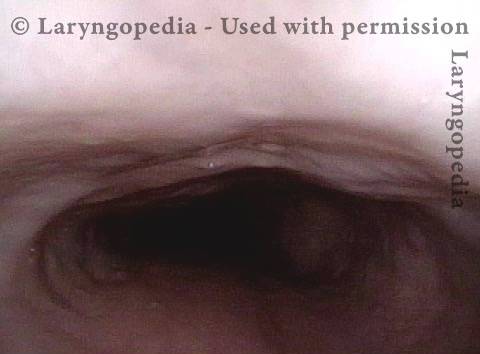

If you care to see this on a model, look at the photos below.

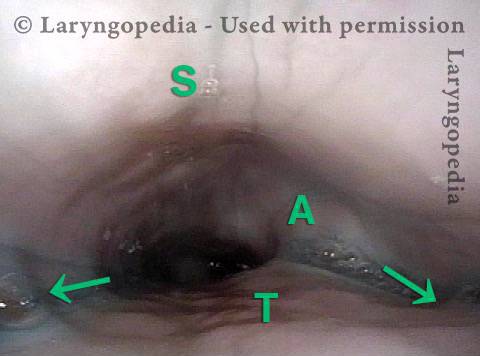

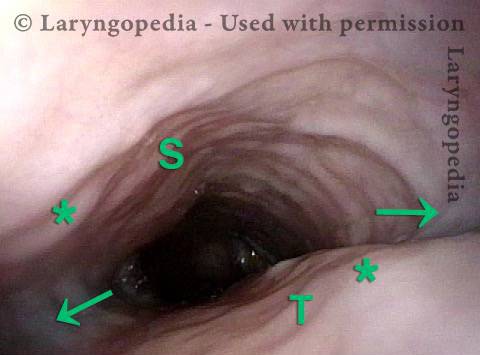

Cricopharyngeus Muscle (1 of 3)

Cricopharyngeus Muscle (1 of 3)

Open Cricopharyngeus Muscle (2 of 3)

Open Cricopharyngeus Muscle (2 of 3)

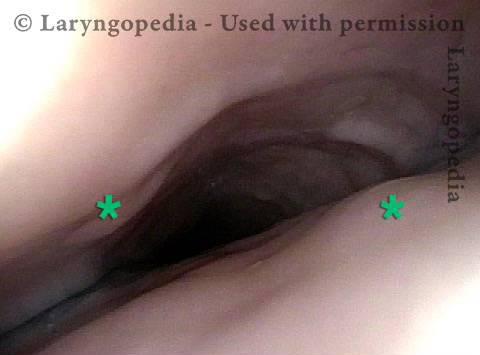

Closed (3 of 3)

Closed (3 of 3)

That sphincter muscle relaxes for about a second every time we swallow saliva, food, or drink. All of the rest of the time it is contracted. Whenever a person belches, the same sphincter needs to let go for a split second in order for the excess air to escape upwards. In other words, just as it is necessary that the sphincter “let go” to admit food and drink downwards in the normal act swallowing, it is also necessary that the sphincter be able to “let go” to release air upwards for belching.

People who cannot release air upwards are miserable. They can feel the “bubble” sitting at the mid to low neck with nowhere to go. Or they experience gurgling when air comes up the esophagus and is blocked by a non-relaxing sphincter. It is as though the muscle of the esophagus continually churns and squeezes without success. The person so wants and needs to burp, but can’t. Sometimes this can even be painful. Such people often experience abdominal bloating as the air must make its way through the intestines before finally being released as flatus.

For people who experience this problem to the point of discomfort and reduced quality of life, here is one approach: First, a videofluoroscopic swallow study, perhaps with effervescent granules. This establishes that the sphincter works normally in a forward (antegrade) swallowing direction, but not in a reverse (retrograde) burping or regurgitating fashion. Along with the symptoms described above, this establishes the diagnosis of retrograde-only cricopharyngeus dysfunction (non-relaxation).

Second, a treatment trial involving placement of Botox into the malfunctioning sphincter muscle. The desired effect of Botox in muscle is to weaken it for at least several months. The person thus has many weeks to verify that the problem is solved or at least minimized. The Botox injection could potentially be done in an office setting, but we recommend the first time (at least) placing it during a very brief general anesthetic in an outpatient operating room. That’s because the first time, it is important to answer the question definitively, that is, that the sphincter’s inability to relax when presented with a bubble of air from below, is the problem.

For a few months at least, patients should experience dramatic relief of their symptoms. And, early experience suggests that It may be that this single Botox injection allows the system to “reset” and the person may never lose his or her ability to belch. Of course, if the problem returns, the individual could elect to pursue additional Botox treatments, or in a truly severe case, might even elect to undergo endoscopic laser cricopharyngeus myotomy.

Lifting the CPM for a R-CPD Injection

These are intra-operative photos of one of nearly 1500 persons treated for R-CPD as of September 2023. This sequence shows several things: The dilated, “always open” esophagus distal (below) the muscle; how to identify the cricopharyngeus muscle; and one way of injecting it.

Above the CPM (1 of 5)

Above the CPM (1 of 5)

Ridge of the CPM (2 of 5)

Ridge of the CPM (2 of 5)

Exposed CPM ( 3 of 5)

Exposed CPM ( 3 of 5)

CPM Palpated ( 4 of 5)

CPM Palpated ( 4 of 5)

Botox injection ( 5 of 5)

Botox injection ( 5 of 5)

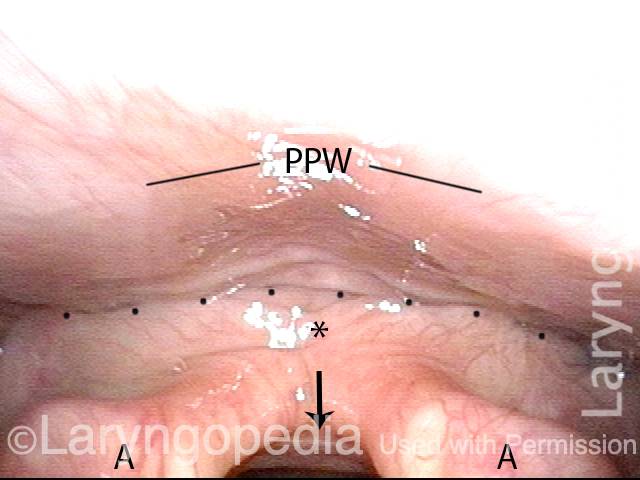

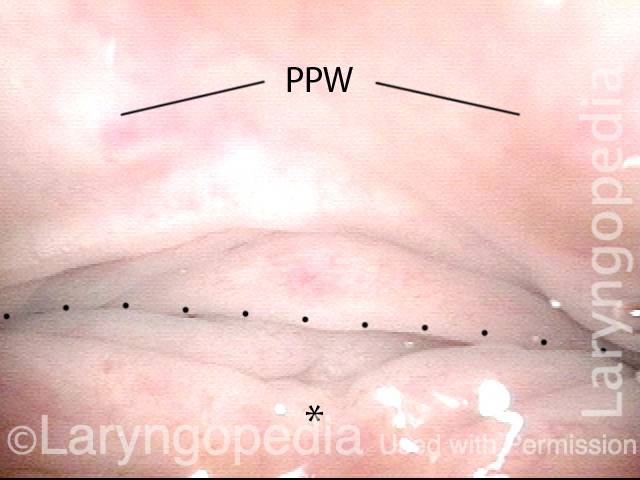

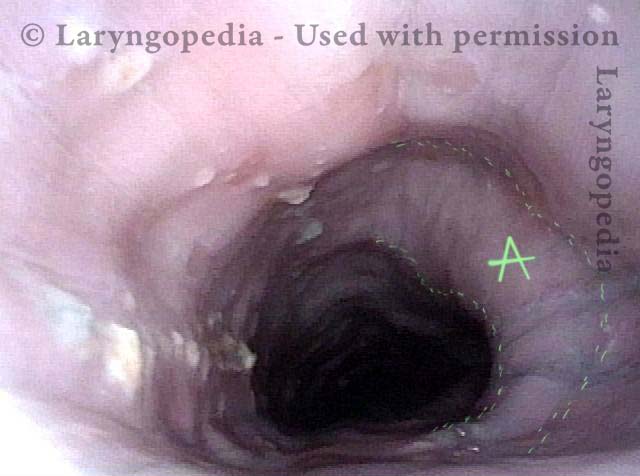

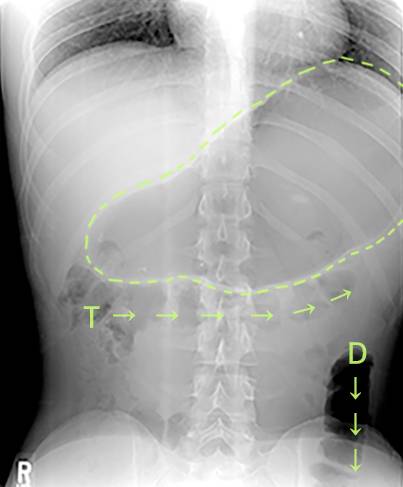

R-CPD and Esophageal Dilation

Posterior pharyngeal wall (1 of 3)

Posterior pharyngeal wall (1 of 3)

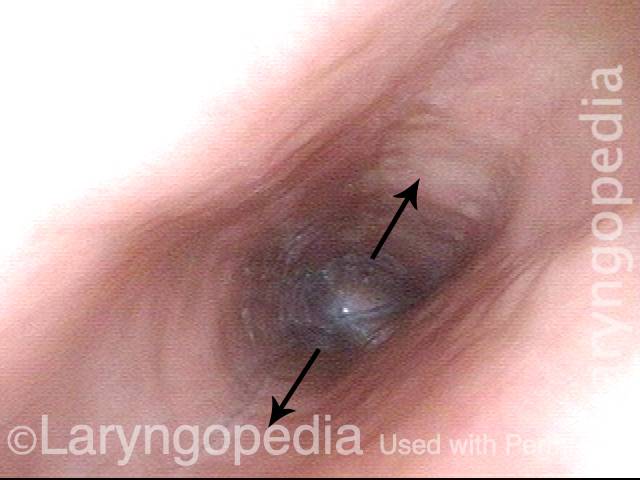

Is it R-CPD? (2 of 3)

Is it R-CPD? (2 of 3)

Stretched esophagus indicates R-CPD (3 of 3)

Stretched esophagus indicates R-CPD (3 of 3)

Can’t Burp: Progression of Bloating and Abdominal Distention – a Daily Cycle for Many with R-CPD

This young woman has classic R-CPD symptoms—the can’t burp syndrome. Early in the day, her symptoms are least, and abdomen at “baseline” because she has “deflated” via flatulence through the night. In this series you see the difference in her abdominal distention between early and late in the day. The xray images show the remarkable amount of air retained that explains her bloating and distention. Her progression is quite typical; some with R-CPD distend even more than shown here especially after eating a large meal or consuming anything carbonated.

Side view of a bloated abdomen (1 of 6)

Side view of a bloated abdomen (1 of 6)

Front view (2 of 6)

Front view (2 of 6)

Greater Distention (3 of 6)

Greater Distention (3 of 6)

Front view of bloating stomach (4 of 6)

Front view of bloating stomach (4 of 6)

X-ray of trapped air (5 of 6)

X-ray of trapped air (5 of 6)

Side view (6 of 6)

Side view (6 of 6)

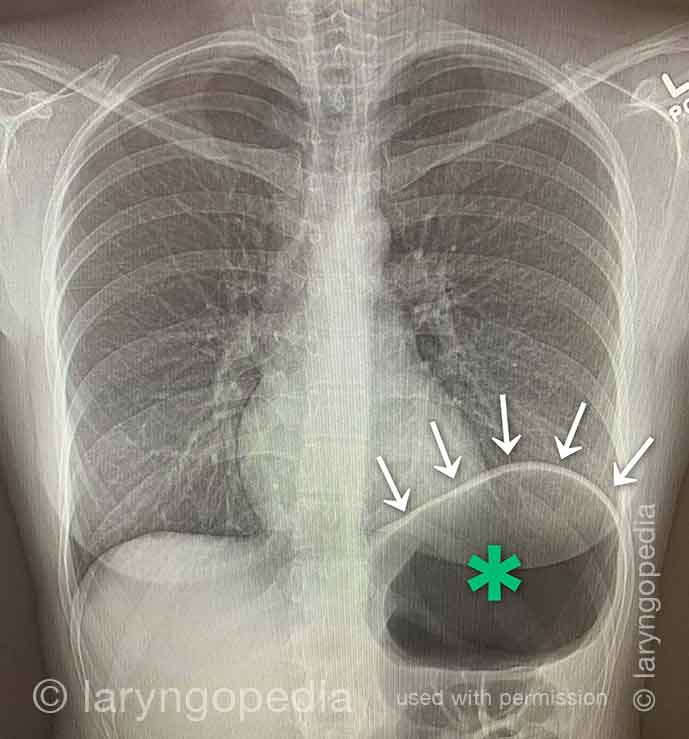

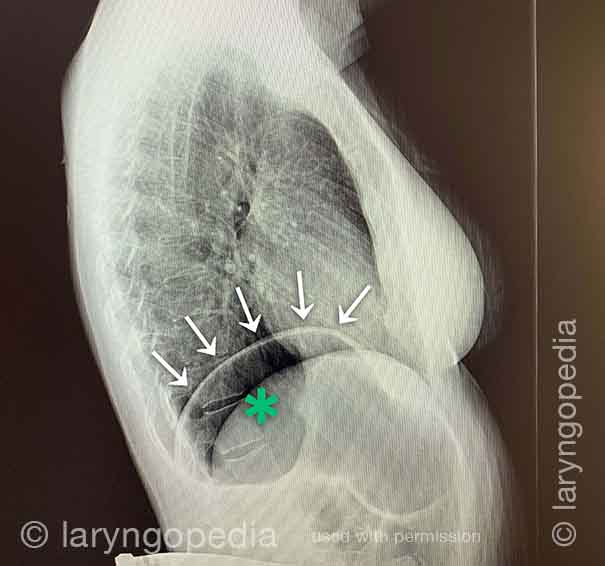

Shortness of Breath Caused by No-Burp (R-CPD)

Persons who can’t burp and have the full-blown R-CPD syndrome often say that when the bloating and distention are particularly bad—and especially when they have a sense of chest pressure, they also have a feeling of shortness of breath. They’ll say, for example, “I’m a [singer, or runner, or cyclist or _____], but my ability is so diminished by R-CPD. If I’m competing or performing I can’t eat or drink for 6 hours beforehand.” Some even say that they can’t complete a yawn when symptoms are particularly bad. The xrays and video below explain how inability to burp can cause shortness of breath.

X-ray of trapped air (1 of 2)

X-ray of trapped air (1 of 2)

Side view (2 of 2)

Side view (2 of 2)

The Esophagus Doesn’t Like Being Stretched for Years Due to Untreated R-CPD

Lateral dilation from R-CPD (1 of 3)

Lateral dilation from R-CPD (1 of 3)

Lateral dilation in the upper esophagus (2 of 3)

Lateral dilation in the upper esophagus (2 of 3)

Medial-lateral stretch (3 of 3)

Medial-lateral stretch (3 of 3)

Esophageal Findings

Aortic shelf (1 of 3)

Aortic shelf (1 of 3)

Bony spur emerges due to stretched esophagus (2 of 3)

Bony spur emerges due to stretched esophagus (2 of 3)

Stretched esophagus due to unburpable air (3 of 3)

Stretched esophagus due to unburpable air (3 of 3)

Abdominal Distention of R-CPD

Gastric Air Bubble (1 of 3)

Gastric Air Bubble (1 of 3)

Bloated Abdomen (2 of 3)

Bloated Abdomen (2 of 3)

Non-bloated Abdomen (3 of 3)

Non-bloated Abdomen (3 of 3)

What the Esophagus Can Look Like “Below A Burp”

Baseline (1 of 3)

Baseline (1 of 3)

Pre-burp (2 of 3)

Pre-burp (2 of 3)

Post-burp (3 of 3)

Post-burp (3 of 3)

Complications Compared to Expected Early Botox Effects in Treatment of R-CPD

People ask: “What could go wrong, if I receive a botox injection for my inability to burp and associated symptoms caused by retrograde cricopharyngeus dysfunction (R-CPD)?”

In this video, Dr. Bastian distinguishes the difference between early EFFECTS that are expected, and COMPLICATIONS patients have experienced in a caseload of approximately 870 people. This informal discussion will likely reassure persons considering this treatment for the severe daily misery caused by R-CPD.