Botox™ (Botulinum Toxin)

Botox™, the trade name of botulinum toxin, is a drug produced by the same bacterial organism (Clostridium botulinum) that causes the disease process called botulism.

Tiny, entirely safe quantities of this medication have been used for decades to treat strabismus, facial spasms, spasmodic dysphonia, cervical dystonia, and other neurological disorders characterized by abnormal muscle contractions. Botox is also used by cosmetic surgeons to smooth wrinkles temporarily.

Uses for Botox in the Head and Neck

Botox has many uses in the head and neck. In order of commonness in a laryngology practice:

The larynx, for laryngeal dystonia (causing spasmodic dysphonia)

That condition causes a strained/strangled, or whispery quality, “catches,” or “dropouts” of syllables or words. All of these vocal phenomena result from involuntary spasms in the tiny muscles of the larynx. Relaxation of the spasming muscles smooths out otherwise-unpredictable voice quality and reduces vocal effort.

The upper esophageal sphincter (cricopharyngeus muscle), for retrograde cricopharyngeus dysfunction (R-CPD), aka the no-burp syndrome

In the untreated condition, this muscle refuses to relax to allow burping. The result is gurgling, bloating, and flatulence. Patients often suffer additional symptoms like painful hiccups, a feeling of mechanical shortness of breath, nausea after eating, and hypersalivation.

In this condition, Botox serves relaxes the cricopharyngeus muscle, allowing burping to commence, and serving as “training wheels” for burping, and in turn resolving the condition permanently in about 80% of patients after a single injection.

Eye closure, neck, and jaw muscles for dystonia involving them

Ocular, cervical, oromandibular dystonias (blepharospasm, torticollis, jaw dystonia, respectively). In most medical systems, these are more often treated by neurologists than laryngologists.

Muscles inserting on the skull, for migraine headaches

Tension in these muscles can be the source of migraine pain. Relaxing them with Botox can help.

The upper esophageal sphincter for cricopharyngeal spasm (CPS)

This is an uncommon use, for a small subset of persons whose CPS is unusually severe, and non-responsive to lesser treatments. The idea is to “reset” the hypertonicity of the muscle causing the distressing choking sensation.

Salivary glands

In certain swallowing disorders where patients are having trouble swallowing their saliva, botox injected into salivary glands can reduce salivary flow.

The skin in front of the ear for Frey’s Syndrome

After parotidectomy (removal of the “spit gland” in front of the ear), tiny secretomotor nerve fibers that supplied the gland can reconnect to sweat glands in the skin. When the patient eats, saliva is no longer produced from the removed gland, and sweat can instead drip from the cheek. Botox can reduce this problem.

Facial muscles (cosmetic use)

By relaxing muscles of expression, creases, wrinkles and “action lines” in the skin overlying those muscles are smoothed.

Reframing the Word “Toxin”

The term toxin can understandably be off-putting. Occasionally, individuals who might benefit greatly from treatment decline it outright, saying, “That’s a poison—I’m not putting that in my body.”

What’s often missing is perspective. Scientifically, toxin is simply the term used for any biologically derived substance—produced by bacteria, plants, or animals—that can be harmful in its uncontrolled, natural form. However, many such substances can be purified, precisely measured, and safely administered for profound therapeutic benefit.

A striking example is insulin. One could argue that insulin itself, in the right context, behaves like a toxin—a molecule that can kill. Prior to the 1980s, insulin was harvested from pig or cow pancreases. But around 1980, scientists inserted the human insulin gene into E. coli, transforming these bacteria into insulin-producing “factories.” Since then, millions have relied on this genetically engineered bacterial product to survive. And yet, insulin—so vital and life-saving at appropriate doses—can become lethal at just five times the usual daily dose.

The case of botulinum toxin is similar in principle. In nature, and in uncontrolled exposures, it is indeed dangerous—even deadly in sufficient quantity. But when refined and used in microgram-level doses, it becomes a precision therapeutic tool. Consider: while the estimated lethal dose of botulinum toxin in humans is roughly 3,000 units, a typical laryngeal dose is about 1 unit. That’s a safety margin of 3,000 to 1.

To put that in perspective: very few medications—whether in pill, liquid, or injectable form—could be taken at 3,000 times their typical dose without serious harm, or worse. And yet, botulinum toxin has been used clinically for over 35 years (since FDA approval in 1989), with a track record of both safety and efficacy.

At this clinic, the author first began using botulinum toxin in 1987, and since that time has treated approximately 2,000 unique patients—for conditions such as spasmodic dysphonia and retrograde cricopharyngeus dysfunction (R-CPD). Side effects are acknowledged and managed carefully, but in this large cohort across more than three decades, there have been no toxin-related complications or unexpected adverse events.

In short, “toxin” refers to origin, not danger.

Just as insulin, digitalis, and even radiation can harm—or heal—depending on dose and context, so too can botulinum toxin serve as a safe and transformative medication when used judiciously.

TA-only Paresis after Botox Injection for Spasmodic Dysphonia

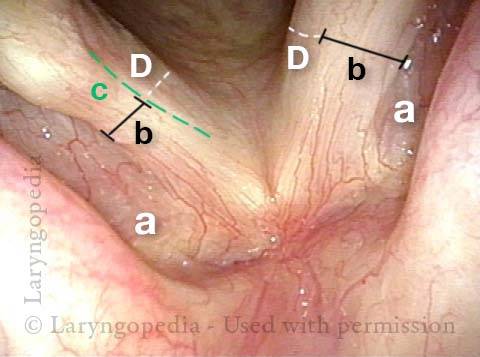

This man with adductory spasmodic dysphonia (AD-SD), has had consistent results during 15 years of botulinum toxin injections, administered several times per year. After his most recent (routine, and unremarkable) injection with his longstanding dose, his initial weakness was exaggerated and is only beginning to subside after six weeks. This dramatic “outlier” result that cannot be attributed to botox targeting. As seen in the photos below, the explanation is instead a right TA-only paresis.

The only reasonable interpretation is that the needle tip has “sheared” the branch of the recurrent laryngeal nerve supplying the thyroarytenoid muscle (leaving branches to the posterior cricoarytenoid and lateral cricoarytenoid muscles (PCA + LCA) undisturbed.

In a practice that supplies treatment to approximately 100 patients per month and ~1200 injections per year, this phenomenon occurs perhaps twice per year. The voice “always” recovers back to baseline SD symptomatology, but excessive breathiness starts to resolve only 6 weeks after the injection.

Right Thyroarytenoid Atrophy (1 of 3)

Right Thyroarytenoid Atrophy (1 of 3)

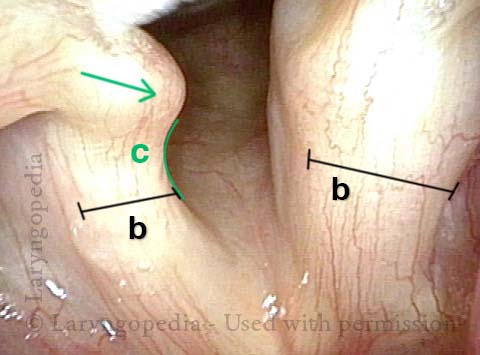

Sharp medial turning (2 of 3)

Sharp medial turning (2 of 3)

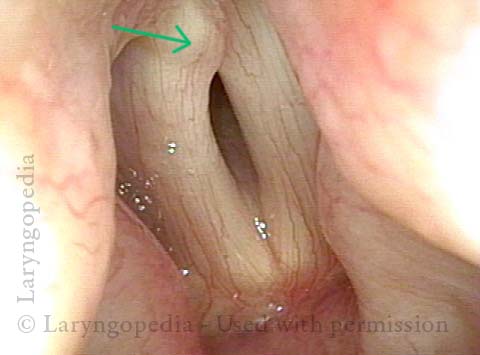

Right vocal process overlaps left vocal process (3 of 3)

Right vocal process overlaps left vocal process (3 of 3)

Lifting the CPM for a R-CPD Injection

These are intra-operative photos of one of nearly 1500 persons treated for R-CPD as of September 2023. This sequence shows several things: The dilated, “always open” esophagus distal (below) the muscle; how to identify the cricopharyngeus muscle; and one way of injecting it.Above the CPM (1 of 5)

Above the CPM (1 of 5)

Ridge of the CPM (2 of 5)

Ridge of the CPM (2 of 5)

Exposed CPM ( 3 of 5)

Exposed CPM ( 3 of 5)

CPM Palpated ( 4 of 5)

CPM Palpated ( 4 of 5)

Botox injection ( 5 of 5)

Botox injection ( 5 of 5)

Uses of Botox in Otolaryngology (Head and Neck)

There are several uses for botox in a laryngology practice. Commonest is for voice (spasmodic dysphonia) and no-burp syndrome (R-CPD), but there are other conditions that may qualify.