Spasmodic Dysphonia (SD, Laryngeal Dystonia)

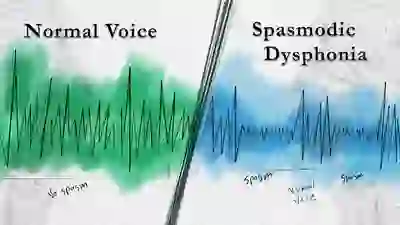

Spasmodic Dysphonia is a non-life-threatening neurological disorder in which the muscles of the larynx involuntarily spasm and interfere with the voice.

Spasmodic dysphonia (SD) is a focal dystonia, in this case involving the larynx—i.e., laryngeal dystonia. Laryngeal dystonia typically affects the voice, but can occasionally also affect breathing (respiratory dystonia). The term spasmodic dysphonia refers specifically to voice-affecting laryngeal dystonia.

Adductor vs. Abductor SD

There are two main variants of SD. In the first variant, adductor SD (AD-SD), the vocal cords are pressed together excessively, intermittently cutting off words or giving the voice a constant strangled quality; this variant comprises 90% of the cases of SD.

In the second variant, abductor SD (AB-SD), the vocal cords are abruptly and momentarily pulled apart while talking, causing the voice to drop out completely or down to a whispery, breathy sound. There are some cases in which a person has both of these variants: this is called mixed AB-AD SD.

Classic vs. Tonic SD

Another distinction that can be made within adductor and abductor, is between classic variant and tonic variant cases of SD. In classic variant SD, the spasms cause phonatory arrests—that is, while the person is speaking, intermittent words or syllables are choked off (with AD-SD) or drop out (with AB-SD).

In tonic variant SD, the spasms are more continuously sustained, so that the voice continuously sounds either strained (with AD-SD) or breathy (with AB-SD), but without any actual phonatory arrests. Because the presence of phonatory arrests is the symptom most often associated with SD, tonic variant SD goes undiagnosed or misdiagnosed far more frequently than does classic variant SD.

See also: Dystonic Tremor

Treatments for Spasmodic Dysphonia

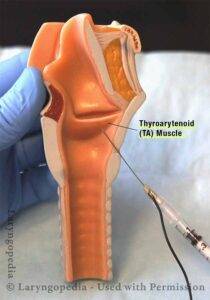

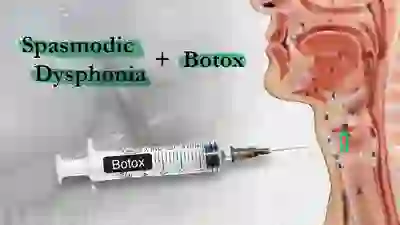

Botox Injections

There is no definitive “cure” for SD, but for most patients, periodic injections of Botox™ into the muscles of the larynx help a great deal, if there is optimal dosage and placement. These injections relax the malfunctioning muscles of the larynx, thereby minimizing the spasms and their impact on the voice.

The effect of an injection typically lasts a few months, and then another injection is needed. For those having difficulty getting good results with Botox™ therapy, see our video below “Spasmodic Dysphonia: When Botox Disappoints.”

What can I expect from Botox injections?

- The initial two or three injections may be needed to establish optimal dose, since there is no way to predict the best dose; instead, these initial injections provide that understanding.

- After each injection, it takes between one and five days, typically, for the Botox effect to be complete.

- If you have AD-SD, we expect transient initial weakness to be a side effect, but your voice should still be functional other than in noisy environments during these initial days. If you have AB-SD, the initial side effect might be mild breathing noises when you exert yourself.

- The golden period of voice quality should last between 8 and 16 weeks on average before another injection is needed. Most people, therefore, receive between 3 and 5 injections per year, and the interval is determined not only by dose, but by individual “biology.”

SLAD-R Surgery

The leading surgical treatment currently offered for SD, Selective Laryngeal Adductor Denervation-Reinnervation (SLAD-R), can be an option for individuals with the AD-SD variant. However, no treatment for SD works satisfactorily for all. The history of each of the several surgical treatments for SD always includes some failures.

Speech Therapy

Speech therapy is another treatment sometimes suggested for SD. While there are strong and even passionate individual proponents of speech therapy, the consensus view is that speech therapy is not expected to substantially improve the voice’s capabilities or reduce spasms other than perhaps in the therapy room1.

A brief course of speech therapy can be very helpful for patient education and perhaps a search for sensory tricks. Much confusion surrounds this subject, because individuals who have a nonorganic voice disorder can be mistakenly diagnosed with SD, and nonorganic voice disorders are routinely “cured” with speech therapy alone.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can Botox Injections Be Used for Singers with SD?

Question:

I have been diagnosed with Spasmodic Dysphonia. I am a professional singer. While SD really bothered my speaking voice, I continued to be able to sing fairly well. I had my first Botox injection 8 weeks ago. So far, I have not returned to a normal speaking voice, and I have lost my ability to sing — it sounds like I have laryngitis.

For the first 3 weeks after the injection, I had no voice at all — I couldn’t even laugh, cough, or clear my throat. My doctor said he gave a very small amount of Botox, since it was my first injection. I just need to know if something is wrong? I’d appreciate anything you can tell me.

Answer:

I’m truly sorry to hear about your difficulty. Since I do not know you personally, my comments should be considered general information based on experience with other singers who have faced similar circumstances.

First, it’s important to understand that Spasmodic Dysphonia (SD) can affect both the speaking and singing voice. However, in some fortunate individuals, spasms occur mainly in the speaking voice, while the singing voice — especially above the chest/head voice transition (the primo passaggio) — remains relatively unaffected. You may have been one of those fortunate few, because SD can otherwise be tragically career-ending for singers.

It’s also important to know that Botox typically rehabilitates the speaking voice more reliably than it restores the singing voice. If a singer continues to sing well despite untreated SD, extreme caution must be used with Botox dosing. Based on your description, even though your doctor reportedly used a low dose, it may still have been too high for your individual sensitivity.

Prolonged, profound breathiness — such as inability to laugh, cough, or clear the throat — strongly suggests that the dose overwhelmed vocal cord function. The good news is that Botox always eventually wears off.

For perspective:

When treating singers, I typically begin with a very small dose — about one-third of a unit, divided equally between the two vocal cords. Even this tiny amount can sometimes be too much, depending on the individual’s sensitivity.

The reaction to an initial injection serves two purposes:

- It provides some initial treatment of the voice, hopefully carefully.

- It reveals how sensitive the individual is to Botox, which helps guide future dosing.

After a few trial doses, some singers find that the best balance they can achieve looks something like this:

- In the first few weeks after an injection, singing is impaired (while speaking improves).

- Then, a “window” of several weeks opens when singing is again possible to some degree.

- Eventually, spasms gradually return, making performance uncertain again.

In your situation, it sounds like the initial dose was too high for your particular sensitivity. Over time, with careful downward adjustment of dosing, it may be possible to find a better balance between speaking and singing — but this can be challenging. The “window” for singing can also vary unpredictably from cycle to cycle, even at the same dose (for example, weeks 3–6 one time, and weeks 5–7 another).

Please stay in close communication with your treating doctor. Know that rehabilitating a singing voice is far more difficult than restoring basic speaking capability, and that achieving a useful “window” for singing will require very individualized and precise dosing strategies.

Do Medications Work in Treating SD?

Medications are not typically highly useful in persons with focal dystonia. We think that all three of these options—speech therapy, surgery, and medication—are on the table.

Yet we continue to see a fourth option as the standard of care for now: periodic Botox injections into the tiny muscles of the larynx (voice box).

You've Used the Word “Neurological." Can it be Psychological Instead?

Not when the diagnosis is clearly SD. Even when the voice problem is clearly established to be SD—that is, neurological—it is understandable that some patients continue to believe their problem is psychological, because the voice change came after a major stressful life event.

Others notice that symptoms are worse when they are stressed or fatigued. They may also note some reduction of symptoms when under the influence of alcohol or a tranquilizer such as valium. Despite these legitimate observations, it is important to remember that the disorder is neurological and not psychological.

Why, then, do the “psychological” effects just mentioned occur? Because though the disorder is neurological, symptoms may be made worse by stress, in the same way that high blood pressure or other disorders may be made worse by stress, too.

Can SD Occur at any Age?

Peak incidence is probably in 50’s and 60’s but can begin in twenties, and I have a few patients under twenty. Gravelly voice of being older is different from this disorder, which includes squeezing, strained quality along with “catches” or lost syllables—or drop-outs to a brief moments of whispering.

Some public persons (who have acknowledged their SD) include Diane Rehm of NPR, Robert Kennedy, Jr, and Scott Adams of Dilbert fame.

Will my SD “Spread" to Affect Other Body Parts?

Once SD is established and obvious, it is not common to develop highly noticeable dystonia in other than laryngeal muscles. Occasionally, however, it does happen. Handwriting might manifest limb dystonia, for example.

Are There Common Experiences Among Persons with SD?

- There may be a long unsuccessful search for diagnosis. The range in our practice is a few weeks to 30 years. The reason for delay is the relative rarity of the disorder, explaining physician unfamiliarity with the diagnosis.

- Patients may have been told (erroneously) that the disorder is psychological.

- Symptoms often vary inexplicably. Persons with SD may notice “good” days and “bad” days, or even “good” moments and “bad” moments. Some experience a lot of variability; others relatively less. Some with a lot of variability attempt to find a dietary, stress-related, or other cause of this variability. To their detriment, patients may have been encouraged to “take responsibility” for this variability when it is much better to understand that variability is simply a known component of the neurological disorder itself.

- Patients may notice that certain words or sounds are especially difficult to say. For example, words beginning with “h” or with a vowel sound are often mentioned. Some persons find their names or phone numbers are hard to say.

- The telephone, drive-up windows, automated phone attendants pose special difficulty. Virtually everyone with SD says, “I hate the telephone!”

What Is the Difference Between SD & Muscle Tension Dysphonia (MTD)?

Keep in mind that MTD and SD are not the same thing. There is a variant of SD that causes strain only (tonic variant SD). In this variant, there are no phonatory arrests (stoppages, catches).

MTD is instead a functional problem that can be treated with very expert therapy. There aren’t many true “experts” on addressing this. Tonic variant SD is a neurological disorder for which Botox is highly effective. Sadly, while Botox can dramatically lessen the symptoms especially in the speaking voice, it cannot return a premier singing voice.

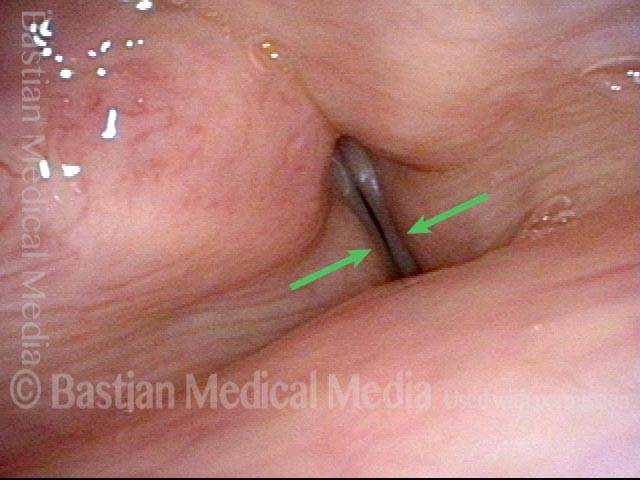

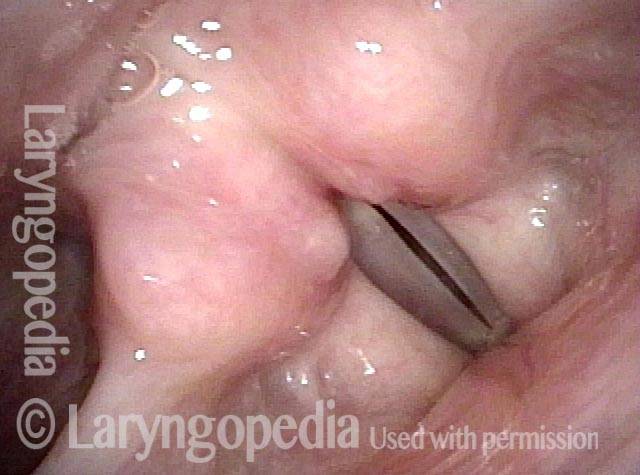

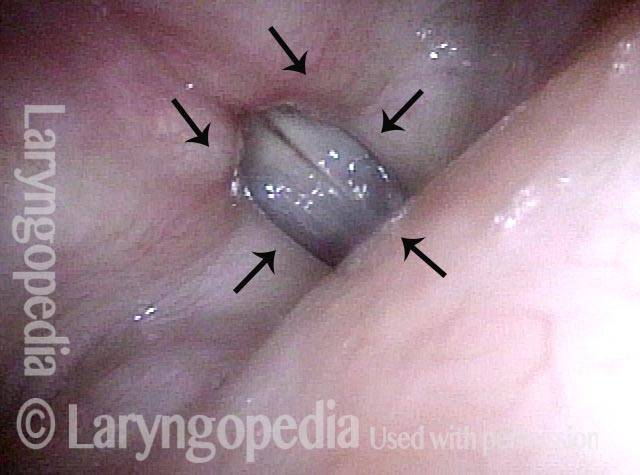

Photo Example of AD-SD

AD-SD (1 of 2)

AD-SD (1 of 2)

AD-SD (2 of 2)

AD-SD (2 of 2)

Example 2

Adductory spasm (1 of 2)

Adductory spasm (1 of 2)

Adductory spasm (2 of 2)

Adductory spasm (2 of 2)

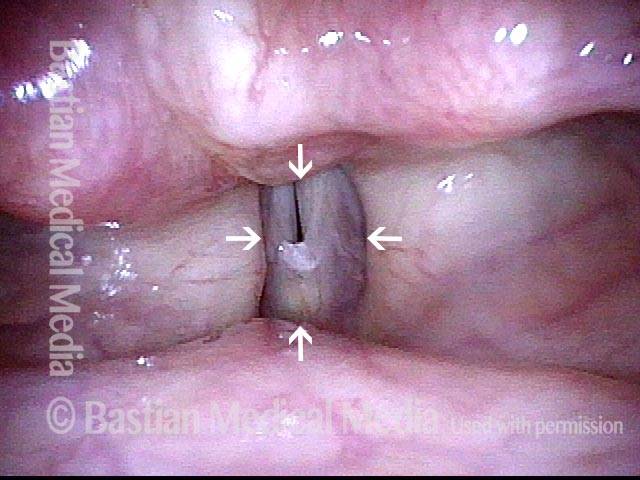

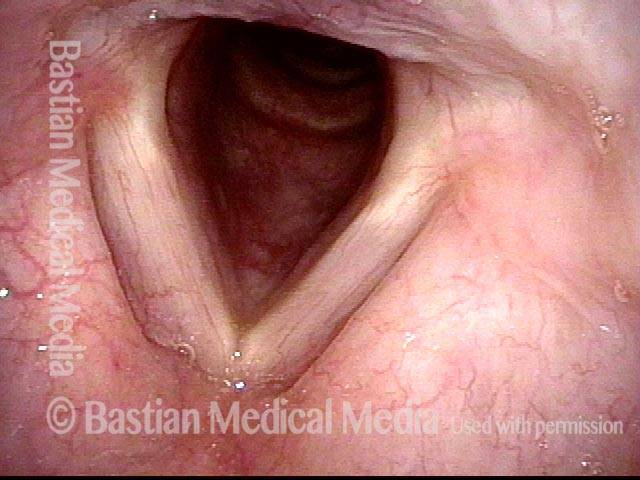

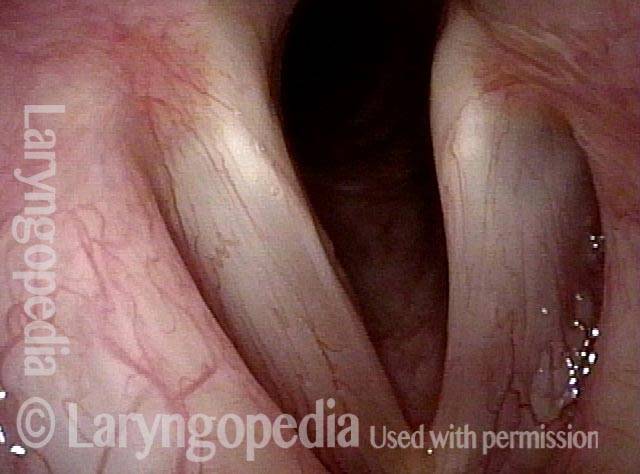

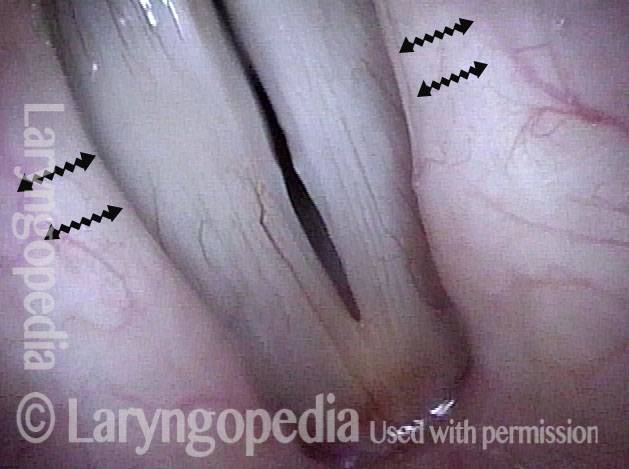

Photo Example of AB-SD

AB-SD (1 of 4)

AB-SD (1 of 4)

AB-SD (2 of 4)

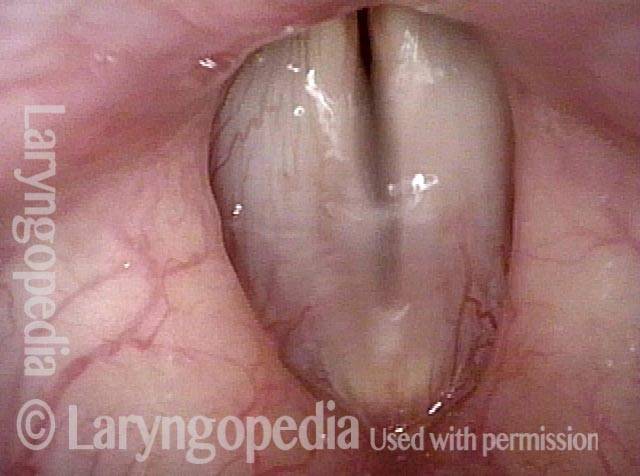

AB-SD (2 of 4)

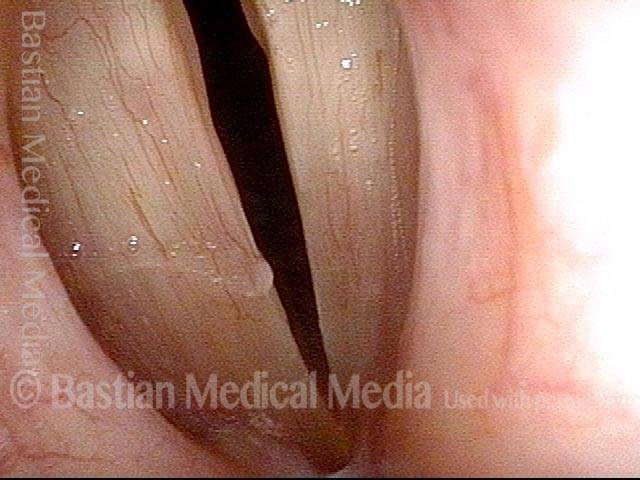

AB-SD (3 of 4)

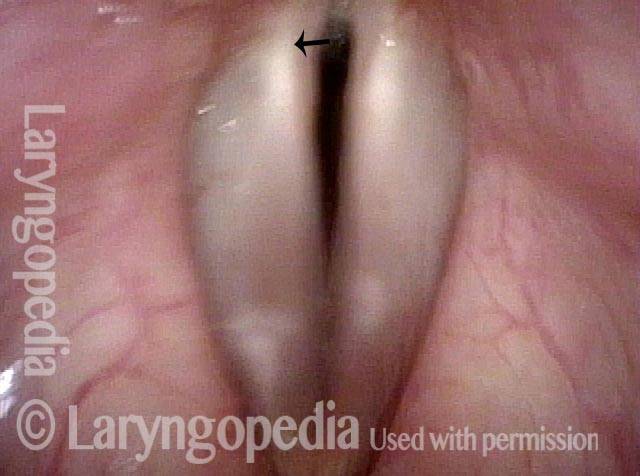

AB-SD (3 of 4)

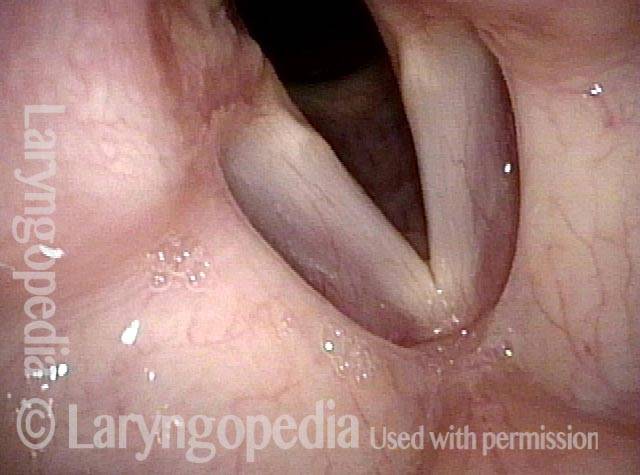

AB-SD (4 of 4)

AB-SD (4 of 4)

Abductor Spasms, Worsened by Cognitive Loading

Abductor spasmodic dysphonia patient (1 of 4)

Abductor spasmodic dysphonia patient (1 of 4)

Limited abductor spasms (2 of 4)

Limited abductor spasms (2 of 4)

Increased abductor spasms (3 of 4)

Increased abductor spasms (3 of 4)

Even greater abductor spasms (4 of 4)

Even greater abductor spasms (4 of 4)

Laryngology 401: PCA-only Paresis, but the Actual Voice Problem Is Spasmodic Dysphonia

Sense of instability (1 of 3)

Sense of instability (1 of 3)

Vibratory amplitude (2 of 3)

Vibratory amplitude (2 of 3)

Spasm (3 of 3)

Spasm (3 of 3)

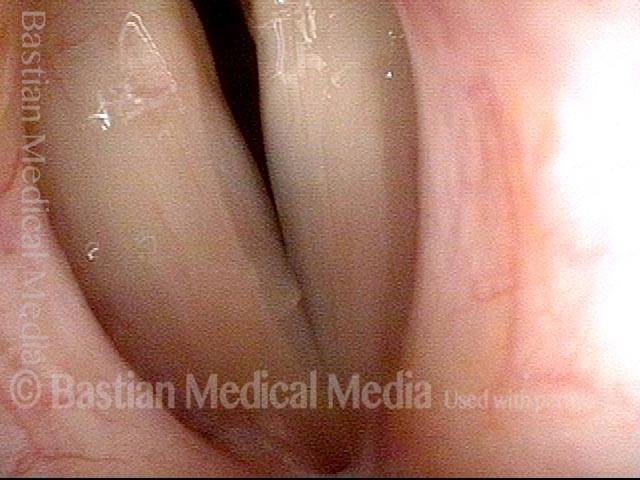

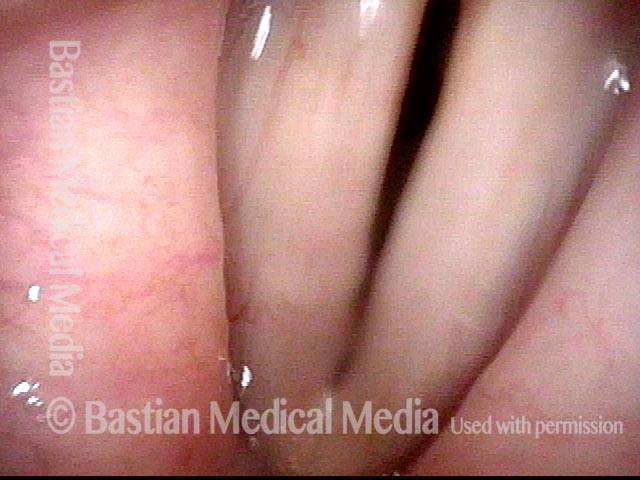

Remarkable Task-Specificity of Spasmodic Dysphonia

Young singer (1 of 4)

Young singer (1 of 4)

Phonation (2 of 4)

Phonation (2 of 4)

Closed phase (3 of 4)

Closed phase (3 of 4)

Sudden spasm (4 of 4)

Sudden spasm (4 of 4)

Assessment of Vocal Phenomenology Protects from Visual Red Herrings

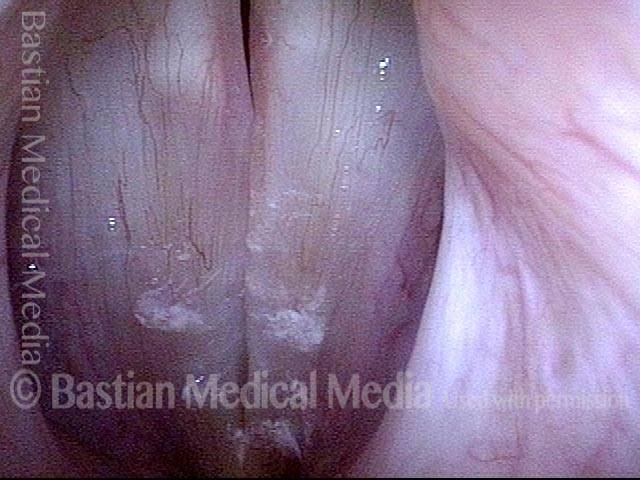

Swelling? (1 of 2)

Swelling? (1 of 2)

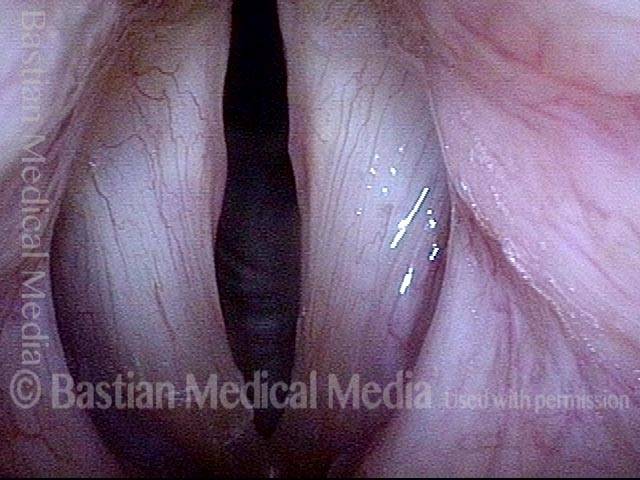

Spasmodic dysphonia (2 of 2)

Spasmodic dysphonia (2 of 2)

Share this article

Table of Contents

Tags

Botox · Disorders · Laryngeal Dystonia · Neurological voice disorders · Photos · Spasmodic Dysphonia (SD) · Videos · Vocal Phenomenology · Vocal Spasm · Vocal Weakness · Voice & other larynx disorders

Video Overview

Dr. Robert Bastian reviews the various types and subtypes of spasmodic dysphonia (SD). Numerous voice examples are included, along with video of the vocal folds.

SD is a rare neurological disorder caused by laryngeal dystonia, and it interferes with the smooth functioning of the voice. Tiny spasms of the vocal folds may cause the voice to catch or cut out, strain or squeeze away, and sometimes to drop momentarily to a whisper.

Spasmodic Dysphonia: When Botox Disappoints

In this video, Dr. Bastian discusses common problems with Botox treatment for spasmodic dysphonia (SD) and offers clear, practical advice to increase the effectiveness of these treatments.

Is my Vocal Weakness from Spasmodic Dysphonia Spasms, or a Botox Side Effect?

Persons with Spasmodic Dysphonia (SD) may describe the one of the effects of that disorder as vocal “weakness.” After treatment with Botox, they may use the same word—“weakness”—to describe one of the early side effects of treatment with Botox. Especially after the initial several injections, before they have become treatment “veterans,” some patients struggle to distinguish between these two kinds of vocal “weakness.”

As a result they may have difficulty communicating whether the next Botox injection should be a higher or lower dose. In an attempt to address this problem, this video compares and contrasts the vocal weakness of SD with the (initial) post-injection Botox-related vocal weakness.

2014 NSDA 25th Anniversary Symposium

In this video, Dr. Bastian leads a panel discussion on Spasmodic Dysphonia.

Why Does Robert Kennedy Jr. Have a Hoarse Voice? The Answer Is SD…

Why Botox Injections for SD Should Be Individualized

Should Botox injection dosage and interval for your Spasmodic Dysphonia be decided by you and your doctor? Or should a "checklist," created by someone who doesn't know you, determine what you and your doctor may and may not do?

Here's a discussion, and patient examples, that explain the crucial importance of the former approach of freedom of choice and individualization!

A Tour of Voice Disorders with a Focus on SD

In this webinar, Dr. Robert W. Bastian provides an overview of the anatomy of the voice and then touches on different types of voice disorders with a focus on spasmodic dysphonia (laryngeal dysphonia).

- Ludlow CL. Treatment for spasmodic dysphonia: limitations of current approaches. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009; 17(3): 160–165. [↩]