Vocal Cord Microsurgery (Microlaryngoscopy)

Vocal cord microsurgery (microlaryngoscopy) is an endoscopic procedure focused upon the larynx, performed under general anesthesia. A hollow lighted tube rests on the upper teeth and the base of the tongue and allows the physician to see the vocal cords. An operating microscope is used to brightly illuminate and highly magnify the vocal cords. Then, tiny instruments and/or a laser are used to remove the abnormality from the vocal cord or cords.

Who Needs Microlaryngoscopy?

The commonest reason is that there is a visible lesion such as nodules, polyps, capillary ectasia (dilated capillaries), epidermoid or mucus retention cyst, glottic sulcus, papilloma, or a known vocal fold cancer. The point is to remove the lesion to improve the sound or capabilities of the voice.

Of course, if a tumor is involved, voice takes second place to removal of the lesion. Removed tissue is always examined by the pathologist, but for most individuals, the need for biopsy is much less than the need for a better voice.

How Is the Procedure Accomplished?

The procedure, aka Microlaryngoscopy, is typically performed in an outpatient operating room during relatively brief general anesthesia. After you are completely asleep, a hollow, lighted “tube”—called a laryngoscope—is placed on the back of the tongue and against the sidewall of the throat, where it rests during the procedure. A microscope is brought into position, aligned with the laryngoscope, and the vocal cords are highly magnified and brightly illuminated.

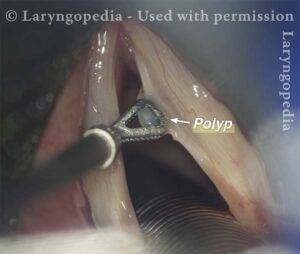

Then, the surgeon uses tiny instruments and / or the carbon dioxide laser, to remove or ablate the problem. Both laser and non-laser tools / methodologies are available for every case, but which tools are used depend upon the nature of the problem. There is nothing innately superior about either method; it is the surgeon and not the tools that matter most. Nevertheless, one tends to use instruments for nodules, polyps, cysts, while the laser is more likely to be used for vascular abnormalities or removal of a vocal fold carcinoma.

Then, the surgeon uses tiny instruments and / or the carbon dioxide laser, to remove or ablate the problem. Both laser and non-laser tools / methodologies are available for every case, but which tools are used depend upon the nature of the problem. There is nothing innately superior about either method; it is the surgeon and not the tools that matter most. Nevertheless, one tends to use instruments for nodules, polyps, cysts, while the laser is more likely to be used for vascular abnormalities or removal of a vocal fold carcinoma.

Time required for the procedure is usually short—10 to 45 minutes of operating time.

Potential Risks

Unless you have significant health issues, risks added together are very small indeed. The three main risks include:

- A truly remote possibility of drug reaction, heart problem, etc., during general anesthesia.

- A very small chance of dental trauma—e.g., chipped, scratched, broken, or dislodged tooth. We have a few instances per year of roughened enamel that doesn’t need a dentist’s attention, but only to be smoothed off in the O.R. Beyond this, about once every 3 years something more significant, such as a broken or dislodged crown or tooth happens.

- We cannot guarantee the precise degree of improvement—whether the result will be “good,” “very good,” or “spectacular.” That depends to large degree on the difficulty of the original problem. And when a known tumor is being removed, we may expect possible worsening of voice quality, as compared to “normal.”

Common Questions about Microlaryngoscopy

What is the chance my voice will be worse after surgery?

The very point of most microlaryngoscopy surgeries is to improve the voice. When we do this kind of surgery in singers—the most discriminating judges of the results of this kind of surgery—both singer/patient and surgeon, not to mention voice teachers, are routinelypleased with the result of surgery. Our expectations do vary a bit, however, with the kind of lesion we are removing.

For example, we expect extremely good results within days with capillary ectasia, nodules, and polyps; good results after cyst or sulcus surgery, though with a much longer and more gradual recovery of voice over months’ time, and so forth. Your surgeon should be able to provide you with an estimate of what kind of voice result is realistic to expect after your surgery.

What about voice use?

Specific advice may vary with the individual. That said, here are the usual voice use restrictions:

Nodules, polyps, capillary ectasia

- No talking for 4 days—usually this means from the day of surgery (Wednesday, for example) to Sunday. During those days, we usually suggest gentle sighing sounds for 10 seconds or so every few hours.

- Talking resumes on Sunday (5th day), but at a restricted amount—you may be a “3” on our 7-point talkativeness scale for one week. If a singer, you may begin vocalizing for 5 minutes twice a day, also beginning Sunday.

- Additional details of postoperative voice use will be explained at your first post-operative visit—typically, you are a “4” for a week; a “5” for a week, and so forth. Vocalizing increases by 5 minutes each practice session, week by week. For singers, we suggest a first (short) voice lesson in the second or third week after surgery.

Cyst, sulcus, papilloma, stenosis, early vocal fold cancer

No voice rest at all, other than one week of what we term “vocal prudence.” This means to talk when you need to, to get the business of life done, but limit “pleasure” talking, and certainly don’t join any street demonstrations!”

When do I see my doctor after surgery?

Typically, we will see you for the first postoperative visit at about a week after surgery (7th day). You will have been talking a couple of days by this time.

If flying home, you may depart the morning after the surgery. It is preferred to see you at some point in the future, but we understand that logistical and cost issues may mean that we never get to see you again! In that case, we do telemedicine follow-ups, and suggest follow-up visits with a laryngologist nearer your home—usually the one who sent you to us in the first place.

What other issues should I expect after surgery?

- You will go home the day of surgery, with rare exception. Of course, you will have to be driven by family member or friend. Most have minimal after-effects from the anesthesia medication. Nausea, for example, has become relatively uncommon.

- You may choose to take medication for a sore throat consisting of either Tylenol or Tylenol with Codeine, barring allergy or sensitivity.

- You may eat whatever your appetite and throat discomfort allow. We do suggest that your first post-operative food be relatively bland, and a small amount, to be sure your stomach is “settled.” Occasionally, salty or acidic food / liquids will burn the sore area caused by pressure from the laryngoscope. Most commonly, that pain will be on the left side.

- Occasionally the teeth feel a little sore and loose, especially your upper central incisors.

What if I forget and talk, or talk in my sleep?

No harm done, just don’t talk knowingly during the initial post-surgery days.

The potential for harm to my teeth really bothers me.

Actually, though dental injury happens so infrequently, this possibility bothers us too! That’s why we use not only a tooth guard, but also all the care and gentleness we can muster while doing your surgery. That said, please keep in mind that you must NOT do this surgery if you cannot personally accept the very small chance of a dental problem. The only way for you to avoid this small risk, and its potential expense to you, is to not have the surgery.

What if my teeth do feel loose?

We suggest that you refrain from wiggling them, or from biting into tough foods until they tighten back up on their own. Most often this takes a week or so.

Suppose I develop a cough after surgery. Will that ruin my voice result?

No—so far the worst outcome I’ve seen in the few times this has occurred is that the person is hoarse a little longer after surgery—it takes somewhat longer for the very early “surgical laryngitis” to resolve. If you do experience a lot of coughing, over-the-counter Robitussin DM suffices for most people. If that is not effective, you can call your physician for a stronger prescription.

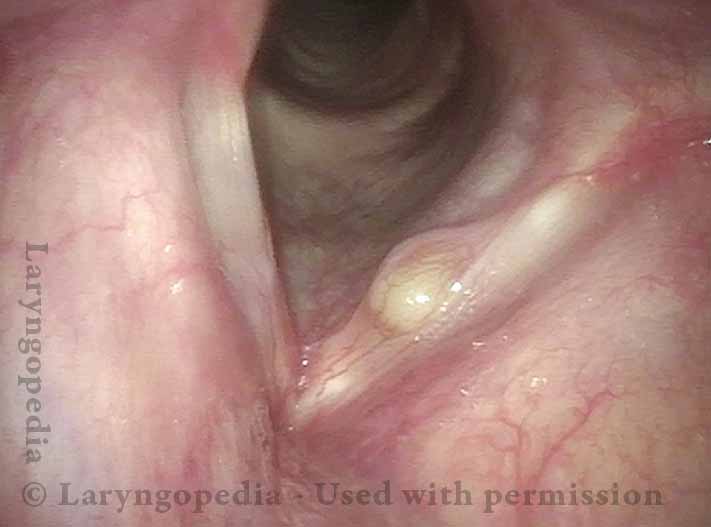

Surgical Removal of a Mucus Retention Cyst

A mucus retention cyst occurs when a small mucus gland becomes plugged and its secretions accumulate, progressively swelling into a cyst. It isn’t known why this happens. There does not seem to be a correlation with vocal overuse, in contrast to vocal nodules, polyps and even epidermoid cysts. Instead, inflammation (viral, or acid reflux-related, for example) seems to be the culprit that plugs the duct of the mucus gland.

In this long series, an older male public speaker presents with severe hoarseness of many months’ duration. Elsewhere, the swelling of his right cord was described as a polyp, rather than a mucus retention cyst. The only solution is microlaryngoscopy; voice therapy is ineffective for this lesion.

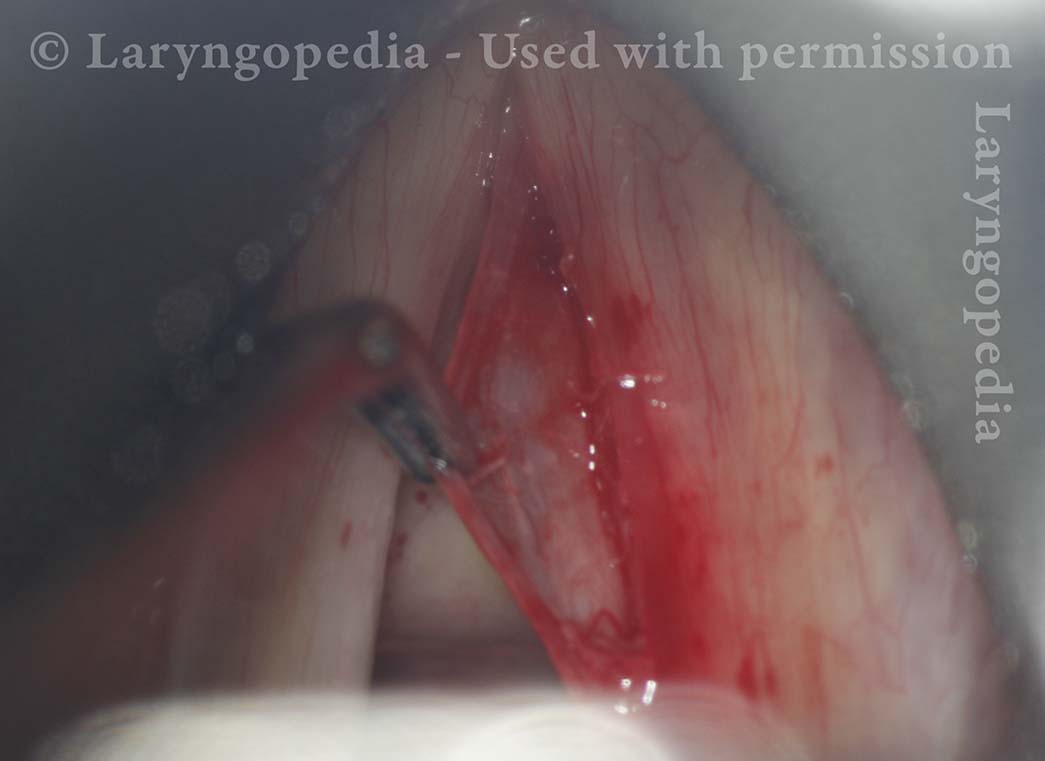

Working with long instruments down a laryngoscope, a very superficial incision is made, the “dragonfly wing” mucosa overlying the cyst is peeled back to expose the cyst. The wall of the cyst itself is also “dragonfly wing” in thickness, making the cyst subject to rupture during removal. Usually if rupture occurs, it is nearing the completion of removal, when most of the dissection has been accomplished and making it possible to remove the entire cyst. In this case, the cyst is delivered intact. Vocal recovery is virtually to normal.

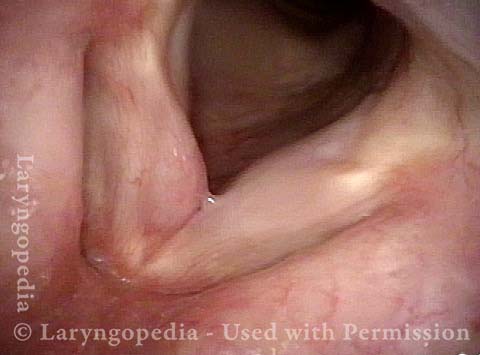

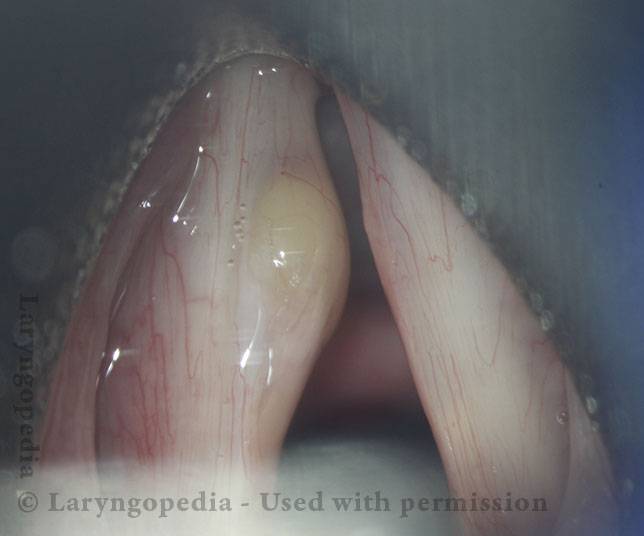

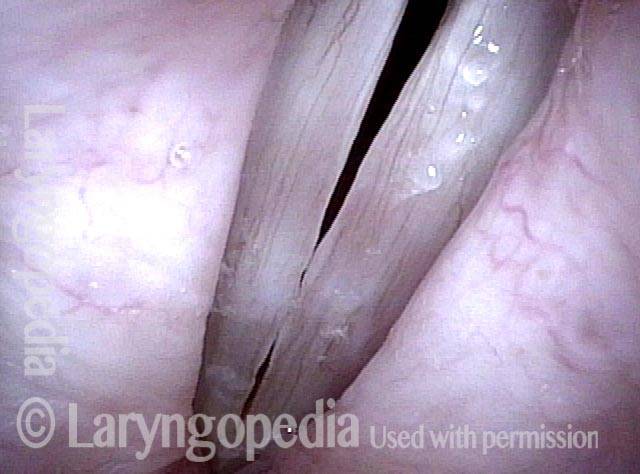

Right vocal cord cyst (1 of 20)

Right vocal cord cyst (1 of 20)

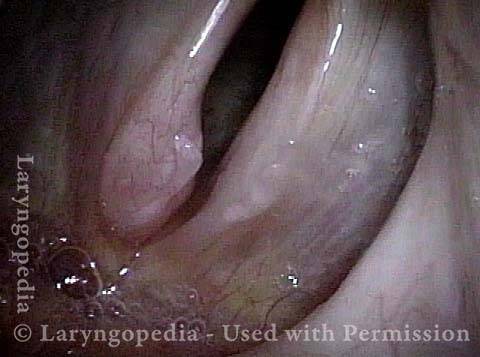

Cyst under strobe illumination (2 of 20)

Cyst under strobe illumination (2 of 20)

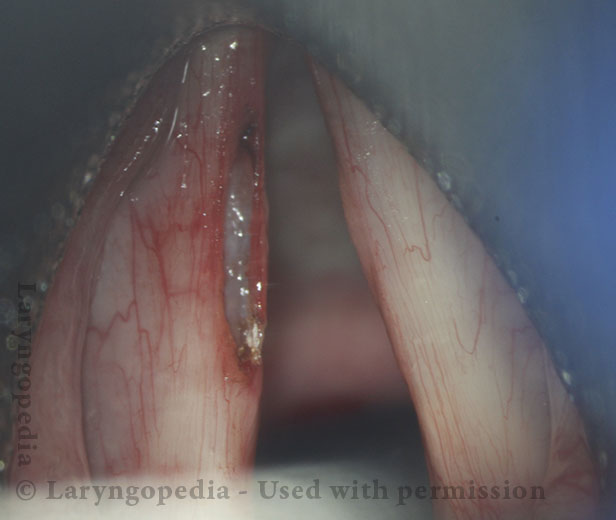

Cyst margin projection (3 of 20)

Cyst margin projection (3 of 20)

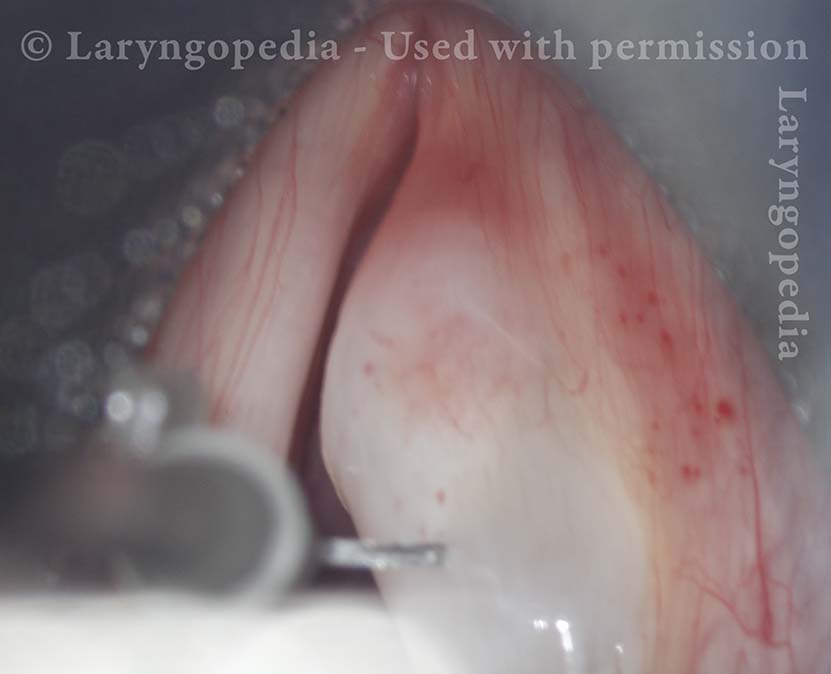

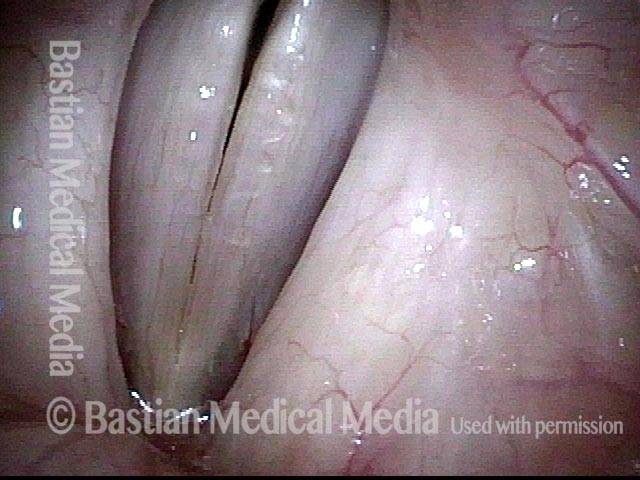

Operating view of cyst (4 of 20)

Operating view of cyst (4 of 20)

Injecting Lidocaine (5 of 20)

Injecting Lidocaine (5 of 20)

Preparing for Microlaryngoscopy (6 of 20)

Preparing for Microlaryngoscopy (6 of 20)

Incision of mucosa (7 of 20)

Incision of mucosa (7 of 20)

Incision in process (8 of 20)

Incision in process (8 of 20)

Dissection of cyst (9 of 20)

Dissection of cyst (9 of 20)

Dissection near complete (10 of 20)

Dissection near complete (10 of 20)

Un-ruptured cyst removal! (11 of 20)

Un-ruptured cyst removal! (11 of 20)

7mm intact cyst (12 of 20)

7mm intact cyst (12 of 20)

Mucosa flap (13 of 20)

Mucosa flap (13 of 20)

Is the voice affected? (14 of 20)

Is the voice affected? (14 of 20)

Voice is much improved! (15 of 20)

Voice is much improved! (15 of 20)

Vocal cord vibrates (16 of 20)

Vocal cord vibrates (16 of 20)

Slight bowing (17 of 20)

Slight bowing (17 of 20)

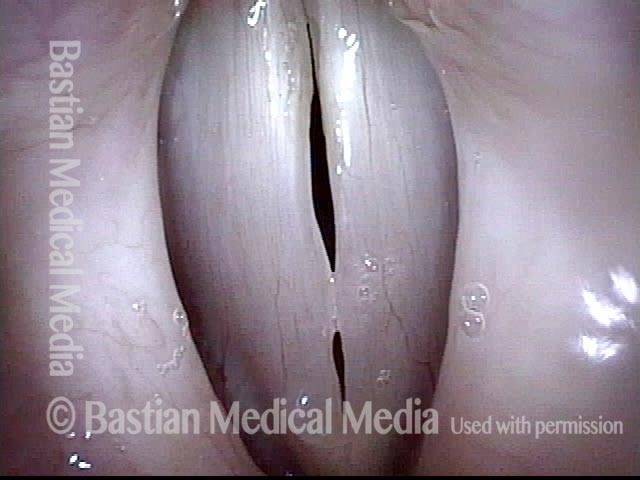

Equal vibratory blur (18 of 20)

Equal vibratory blur (18 of 20)

Reasonable closure (19 of 20)

Reasonable closure (19 of 20)

Voice returns to baseline (20 of 20)

Voice returns to baseline (20 of 20)

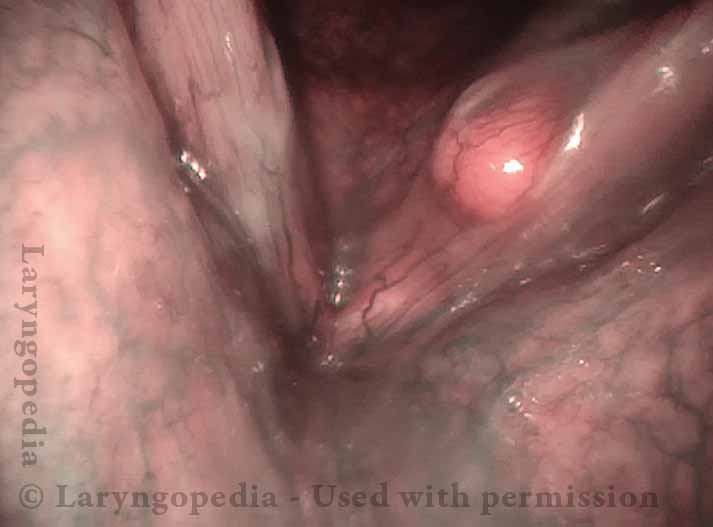

Excision of a Mucus Retention Cyst that Decompresses during Dissection

This man has had slight hoarseness for many years, possibly related to his self-described highly talkative and loud-spoken nature. His voice took a significant turn for the worse soon after a bout of mild laryngitis, and had remained extremely hoarse for many months.

An ENT doctor diagnosed a polyp of his left vocal cord. Instead, this represents a mucus retention cyst. Removal provided dramatic return of clear speaking voice. Seen below is preop, intra-operative sequence, and then the result at 3 months after surgery.

Mucus retention cyst (1 of 17)

Mucus retention cyst (1 of 17)

Closer look (2 of 17)

Closer look (2 of 17)

Cyst under narrow band light (3 of 17)

Cyst under narrow band light (3 of 17)

Cyst interferes with phonation (4 of 17)

Cyst interferes with phonation (4 of 17)

Surgical view (5 of 17)

Surgical view (5 of 17)

After infiltration (6 of 17)

After infiltration (6 of 17)

Lifting the mucosa (7 of 17)

Lifting the mucosa (7 of 17)

Dissecting cyst from deep attachments (8 of 17)

Dissecting cyst from deep attachments (8 of 17)

Cyst has ruptured and emptied (9 of 17)

Cyst has ruptured and emptied (9 of 17)

Dissection of empty sac (10 of 17)

Dissection of empty sac (10 of 17)

Flaps retract (11 of 17)

Flaps retract (11 of 17)

Voice is virtually normal at 3 months (12 of 17)

Voice is virtually normal at 3 months (12 of 17)

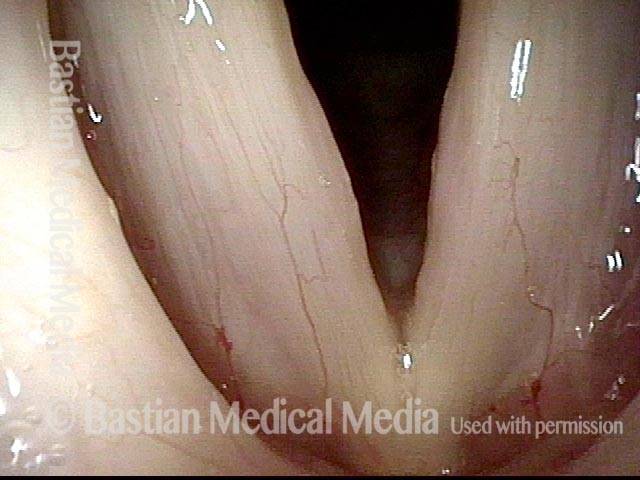

Evidence of vibration, standard light (13 of 17)

Evidence of vibration, standard light (13 of 17)

Open phase at E3 (14 of 17)

Open phase at E3 (14 of 17)

Closed phase at E3 (15 of 17)

Closed phase at E3 (15 of 17)

Open phase at A4 (16 of 17)

Open phase at A4 (16 of 17)

Closed phase at A4 (17 of 17)

Closed phase at A4 (17 of 17)

Amyloidosis of the Larynx as Seen Over Time, with Treatment

Primary laryngeal amyloidosis (1 of 7)

Primary laryngeal amyloidosis (1 of 7)

Bulky swelling (2 of 7)

Bulky swelling (2 of 7)

Amyloidosis (3 of 7)

Amyloidosis (3 of 7)

Amyloid deposits (4 of 7)

Amyloid deposits (4 of 7)

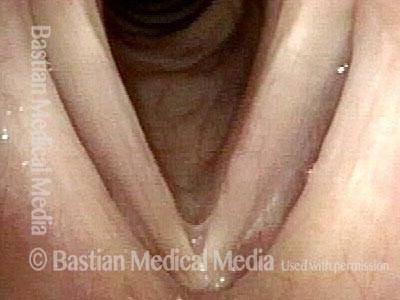

Vocal cords cannot close completely (5 of 7)

Vocal cords cannot close completely (5 of 7)

Amyloids Remain (6 of 7)

Amyloids Remain (6 of 7)

Voice remains clear (7 of 7)

Voice remains clear (7 of 7)

Surgery for Fibrosis, Polyp

Fibrosis + polyp (1 of 4)

Fibrosis + polyp (1 of 4)

Strobe light (2 of 4)

Strobe light (2 of 4)

Post microsurgery, open phase (3 of 4)

Post microsurgery, open phase (3 of 4)

Post microsurgery, open phase (4 of 4)

Post microsurgery, open phase (4 of 4)

Vocal Nodules, Before and After Surgery

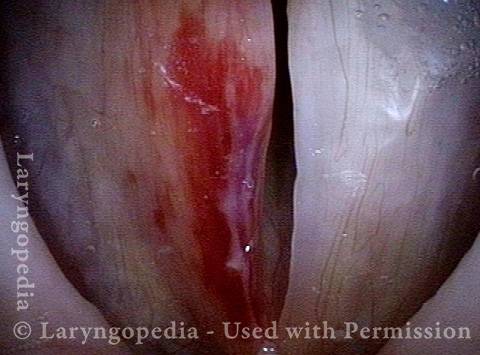

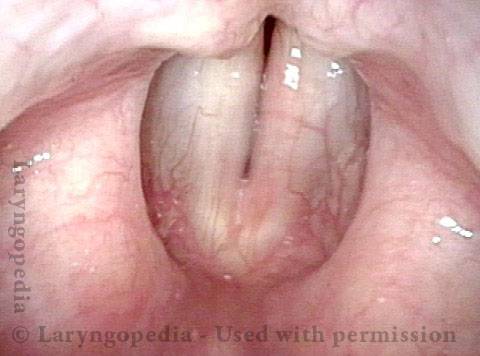

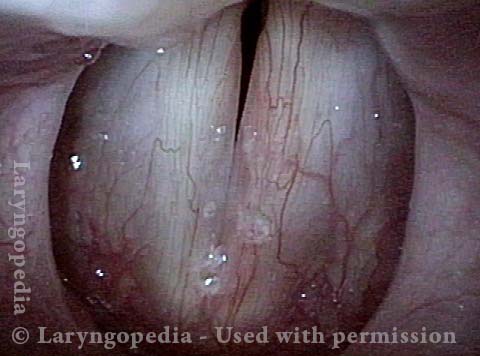

Vocal nodules, before surgery (1 of 4)

Vocal nodules, before surgery (1 of 4)

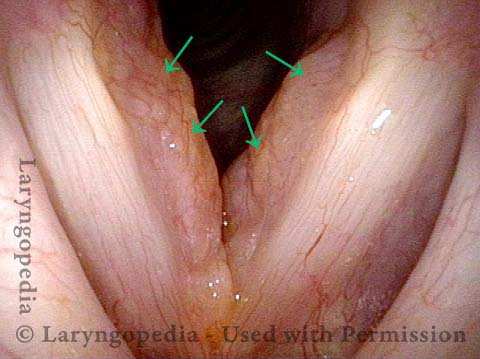

Before surgery (2 of 4)

Before surgery (2 of 4)

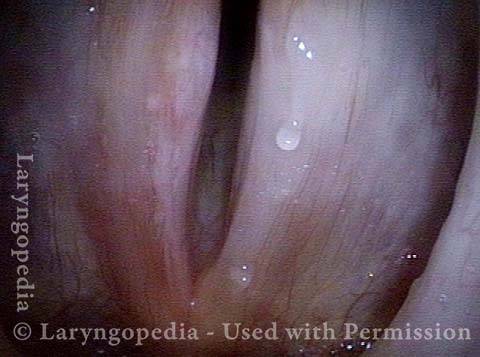

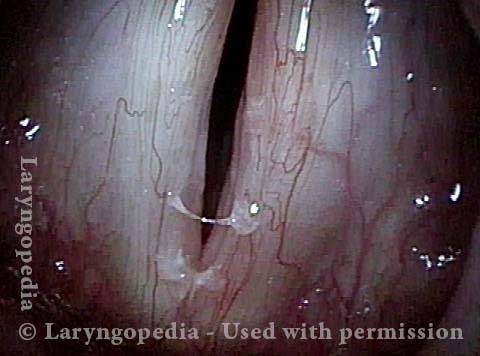

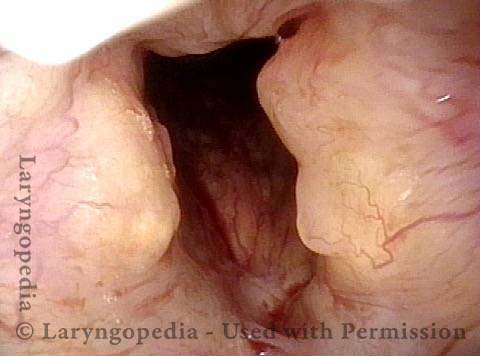

After surgery (3 of 4)

After surgery (3 of 4)

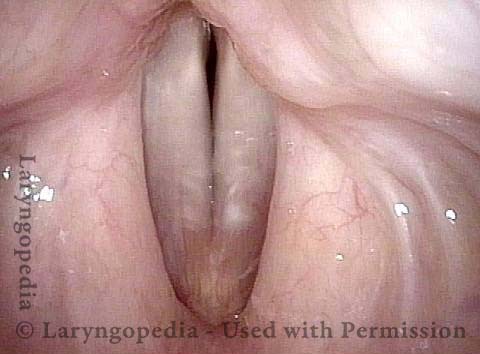

Vocal nodules, after surgery (4 of 4)

Vocal nodules, after surgery (4 of 4)

Share this article

Vocal Cord Microsurgery in Singers Should No Longer Be Controversial

Vocal cord surgery in singers with otherwise irreversible lesions (nodules and polyps for example) is no longer controversial today. But it was not always so…

Some who watch this video may just want to hear before and after examples (voice and vocal cord results). Others may be interested in this personal “trip down memory lane” by Dr. Bastian.

Voice Use after Vocal Cord Microsurgery

Vocal cord microsurgery is reserved for “otherwise irreversible” injury. The risk is low if done well, and the benefit to voice can be major. But what is the blueprint for resumption of voice use (speaking and, if one is a singer, singing) after vocal cord microsurgery? Listen for a recommended plan.