LCA-Only Paresis

LCA-only paresis refers to weakness or paralysis of the vocal cord’s lateral cricoarytenoid (LCA) muscle, but with normal function of the vocal cord’s other muscles. The LCA muscle helps to bring the vocal cord to the midline for voice production and, more specifically, to bring the “toe” of the arytenoid cartilage to the midline.

The following are indicators of LCA-only paresis:

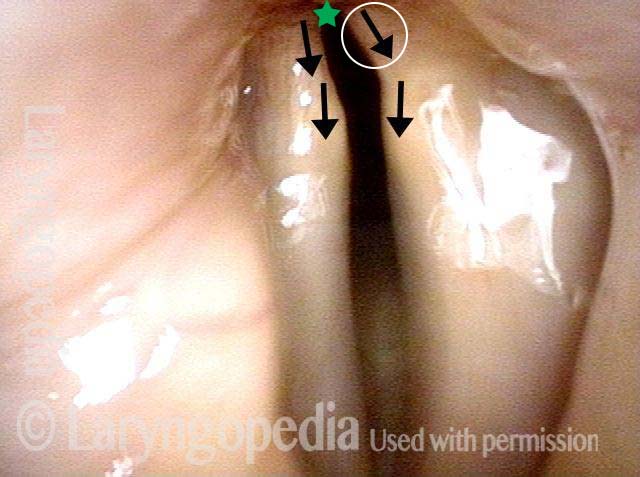

- Movement: The vocal cord opens normally for breathing. From a distance, it can appear to close normally for voicing, but more acute and up-close inspection often shows a faint lag or reduction of crispness of approach to the midline, and inspection of the posterior commissure at close range shows that in fact it does not fully adduct.

- Position and appearance: Position is normal during breathing, but again, the vocal cord does not come fully to the midline for voicing. A tell-tale indicator of LCA-only paresis is lateral turning of the vocal process. This lateral turning is seen best in low voice, and is a little less apparent with very high voice (as illustrated by a pair of photos below).

- Appearance during voicing (under strobe lighting): Persistent slight gap between the vocal cords posteriorly, with the laterally turned vocal process, but no flaccidity of the cord with vibration. Normal tone and bulk of the vocal cord itself.

- Voice quality: Weak and air-wasting, but without the luffing and diplophonia often apparent when the thyroartyenoid (TA) muscle is also paralyzed.

Evolution of Vocal Cord Paralysis To End as PCA-only Paresis

For some voice doctors, measurement is accorded more respect than observation. Both are legitimate, of course, yet, visual (observational) understanding of paralysis and paresis remains far more useful than EMG, acoustic, or aerodynamic measurements. This case strongly illustrates that point.

This older man underwent thoracic surgery but due to complications was also intubated for much of two days. Immediately upon awakening, his voice was altered. He said it was whisper only.

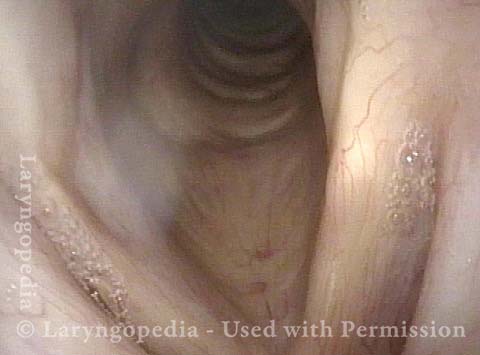

At his original office visit a month later, he thought his voice had improved to “10%” and examination showed left vocal cord paralysis (TA, LCA, and PCA muscles all non-functional). Three months later, his voice was by his description to 40% and improving further week by week. By month 8 post-surgery, verified at 18 months, he felt his voice was “99%” recovered; examination showed recovery of TA and LCA, but not PCA muscle.

The final diagnosis: Left PCA-only paresis. Rather than being entirely “out,” the PCA seems only to be weak.

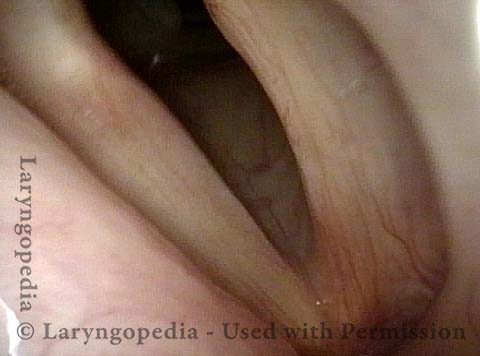

Left Cord Margin Bowing (TA weakness) (1 of 11)

Left Cord Margin Bowing (TA weakness) (1 of 11)

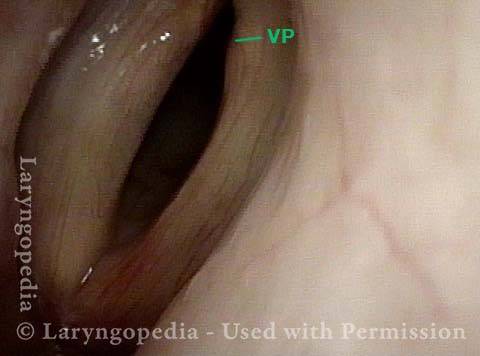

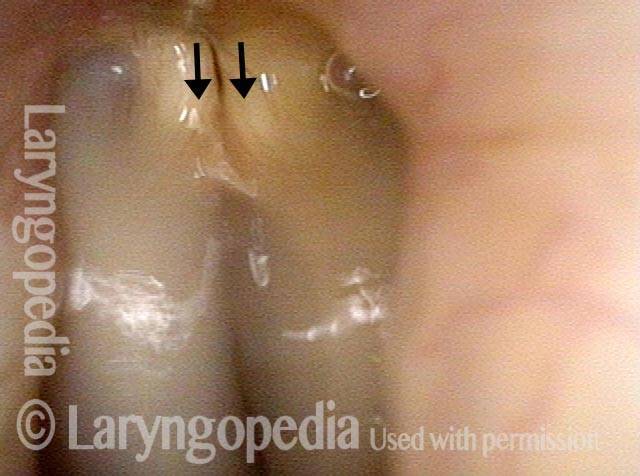

LCA Paresis Identified (2 of 11)

LCA Paresis Identified (2 of 11)

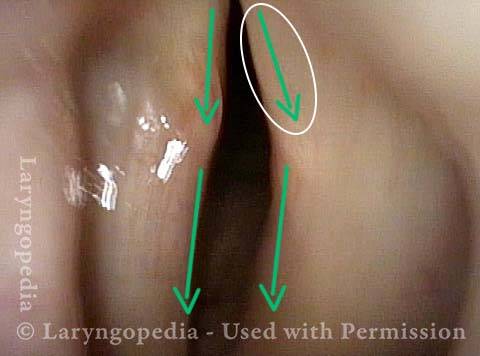

Voice is Breathy! (3 of 11)

Voice is Breathy! (3 of 11)

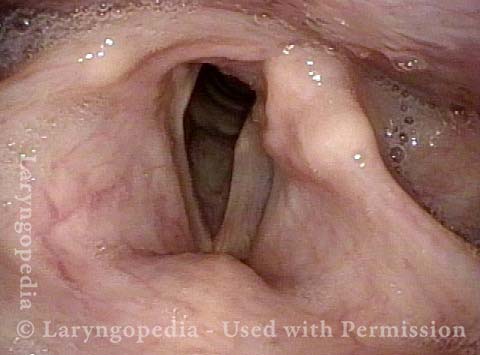

LCA Paresis Best View (4 of 11)

LCA Paresis Best View (4 of 11)

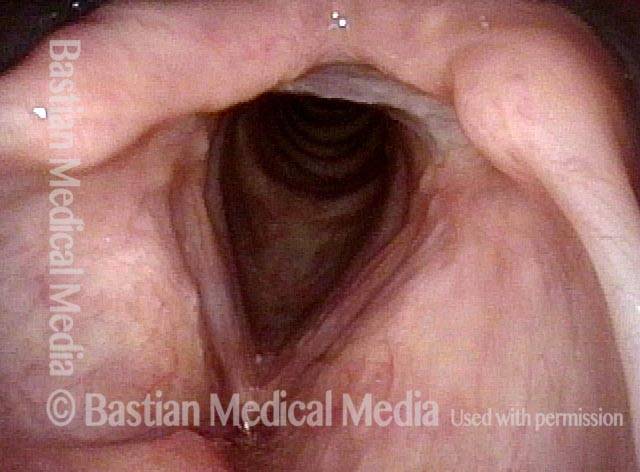

4 Months Later, Glottis Open For Breathing (5 of 11)

4 Months Later, Glottis Open For Breathing (5 of 11)

Gap during phonation less (6 of 11)

Gap during phonation less (6 of 11)

PCA Weakness Is All That remains (7 of 11)

PCA Weakness Is All That remains (7 of 11)

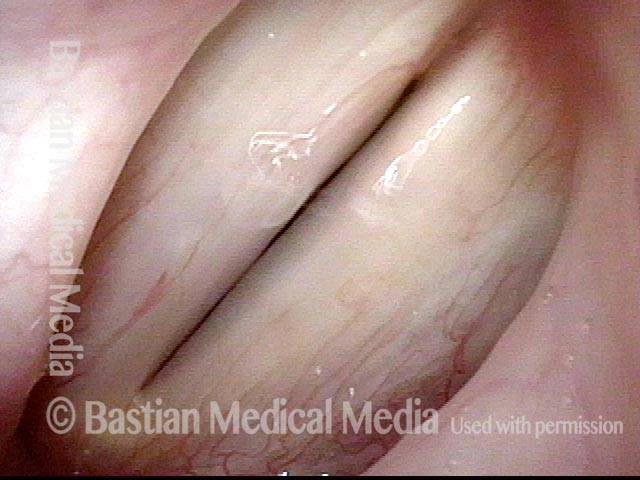

LCA Recovered: The Vocal Process Now Turns Medially (8 of 11)

LCA Recovered: The Vocal Process Now Turns Medially (8 of 11)

At 18M, Left Cord Does Not Abduct Due To Continuing PCA Weakness (9 of 11)

At 18M, Left Cord Does Not Abduct Due To Continuing PCA Weakness (9 of 11)

Left PCA Can Muster Some Lateralization (10 of 11)

Left PCA Can Muster Some Lateralization (10 of 11)

Full Recovery for Voicing, Despite PCA-Only Paresis (11 of 11)

Full Recovery for Voicing, Despite PCA-Only Paresis (11 of 11)

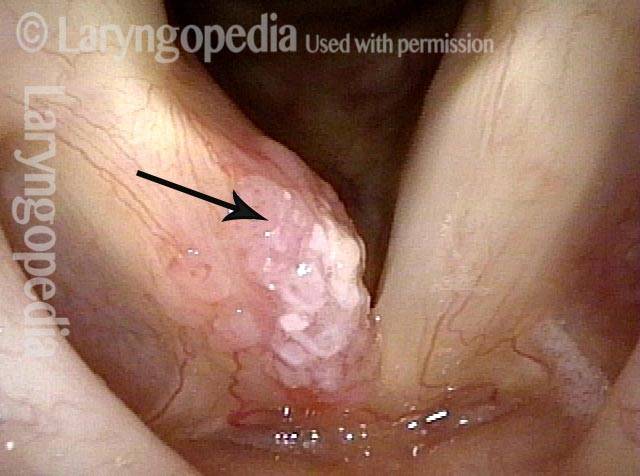

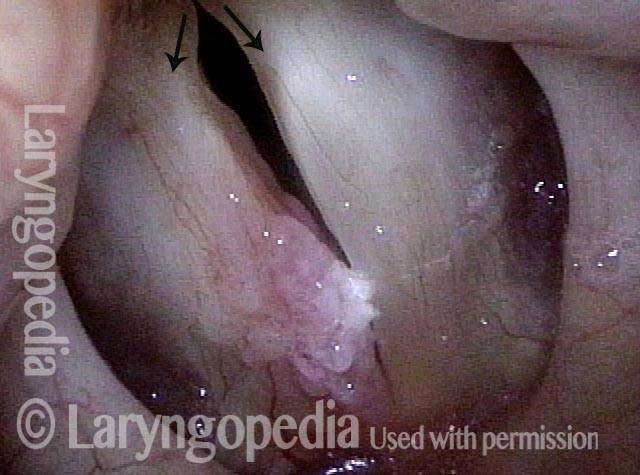

LCA Weakness

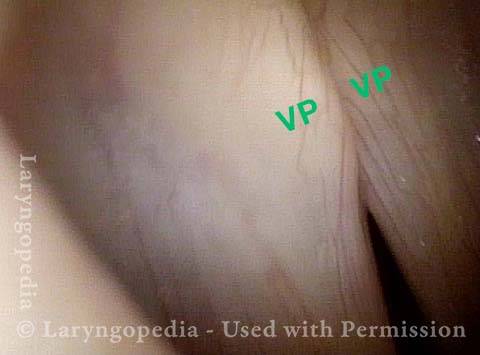

Lateral cricoarytenoid (LCA) weakness is best seen during phonation. Lateral turning of the vocal process during voicing is the “key” finding, though there are others. We say the “toe” (tip of vocal process) is turned laterally. The “heel” of the arytenoid is together, signifying normal function of the interarytenoid (IA) muscle.

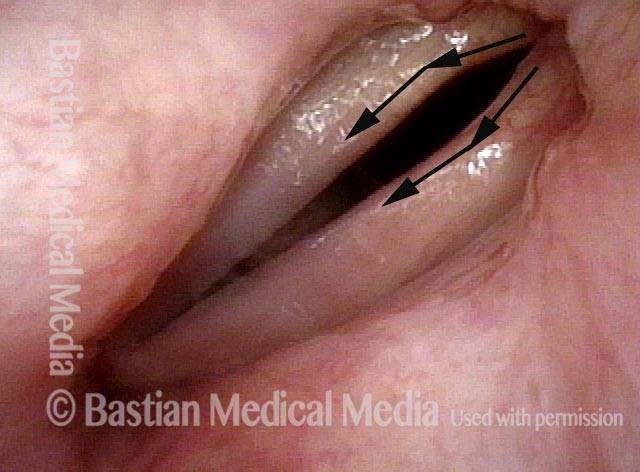

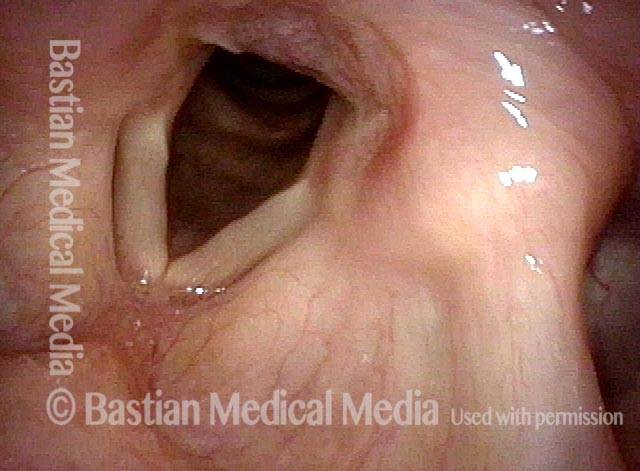

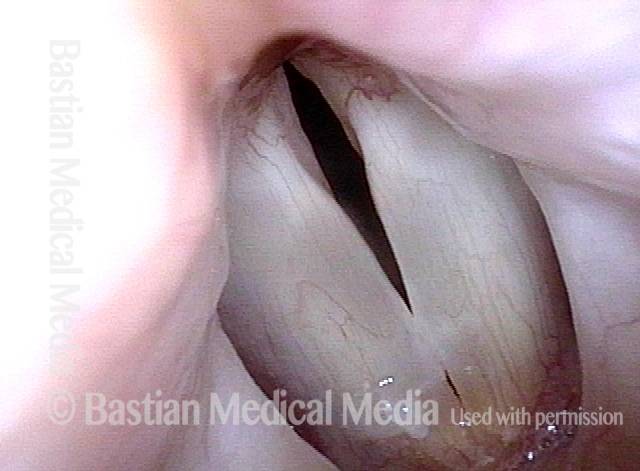

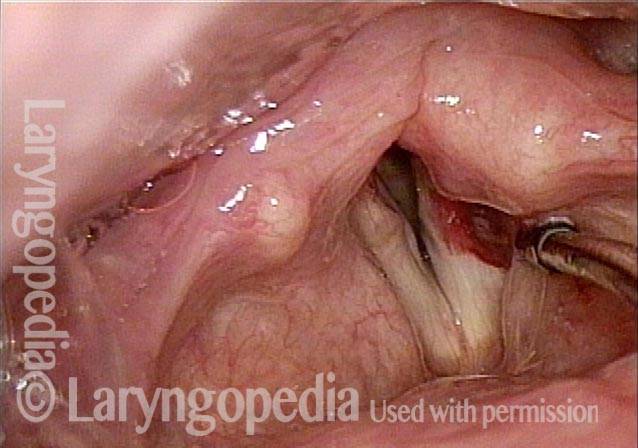

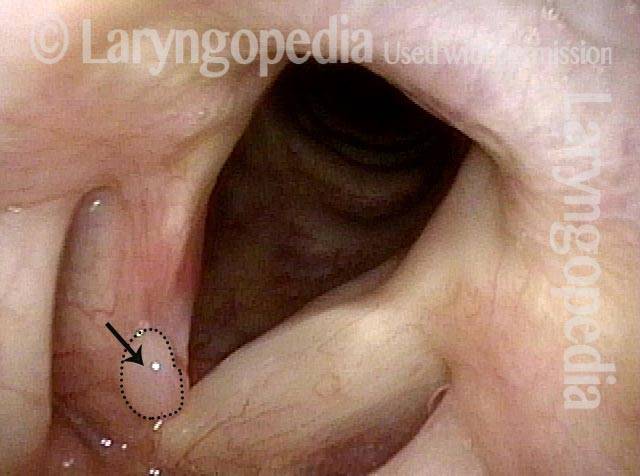

LCA weakness, in a patient with vocal cord paralysis (1 of 4)

LCA weakness, in a patient with vocal cord paralysis (1 of 4)

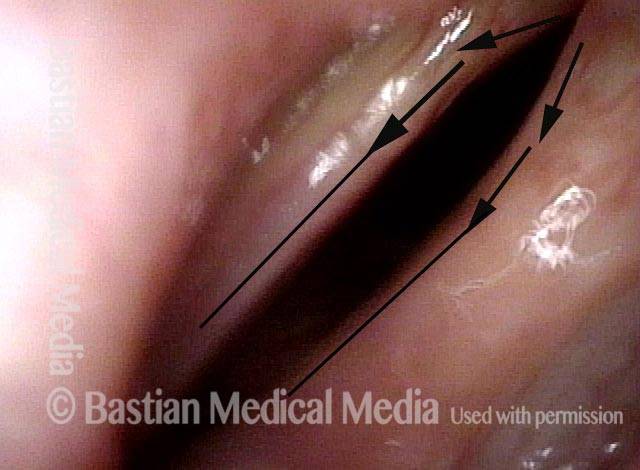

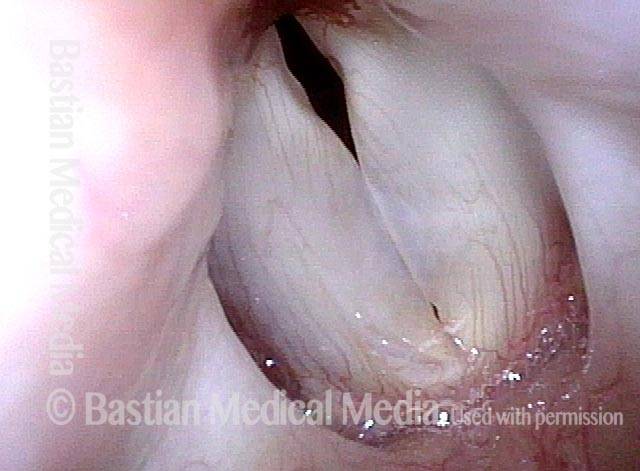

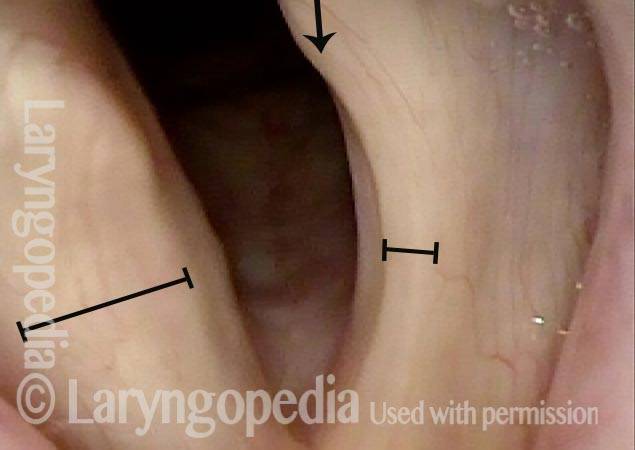

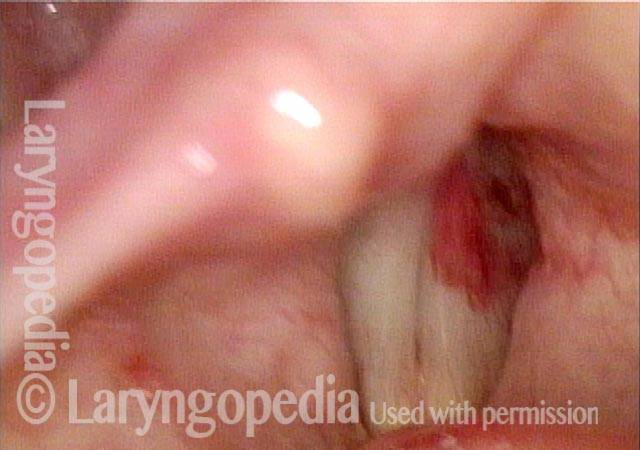

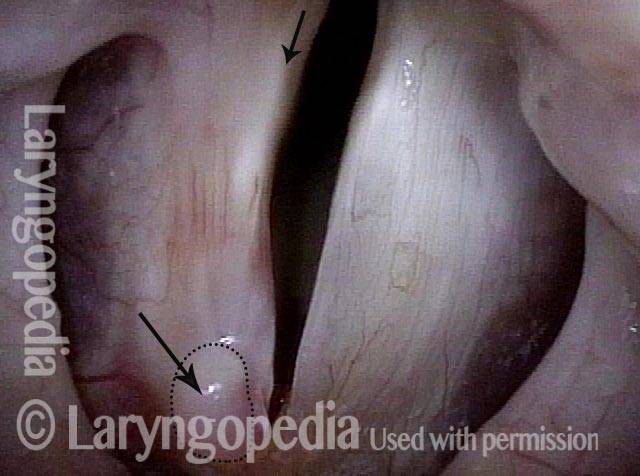

LCA weakness, masked by high pitch (2 of 4)

LCA weakness, masked by high pitch (2 of 4)

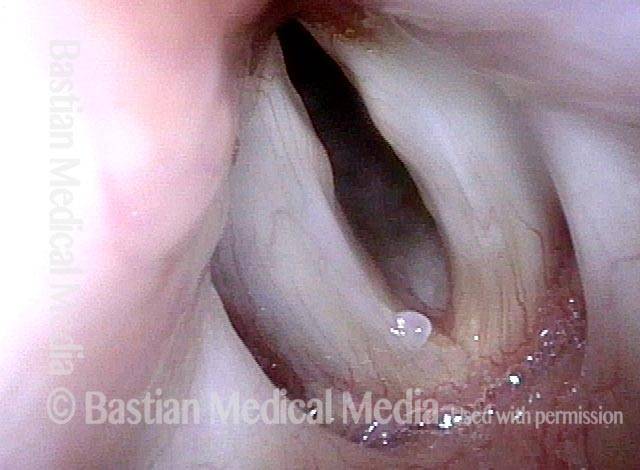

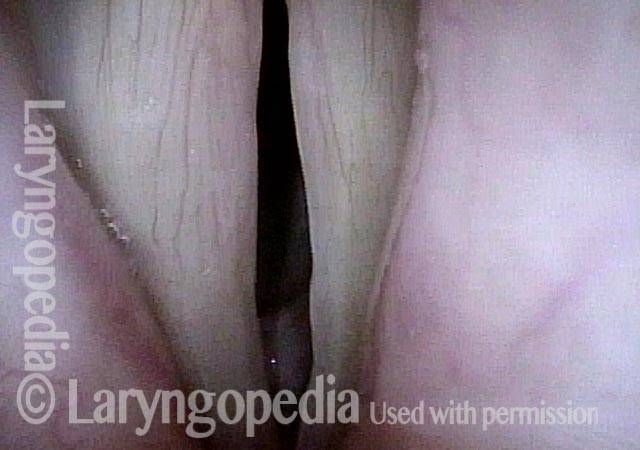

Imposed breathy voice (3 of 4)

Imposed breathy voice (3 of 4)

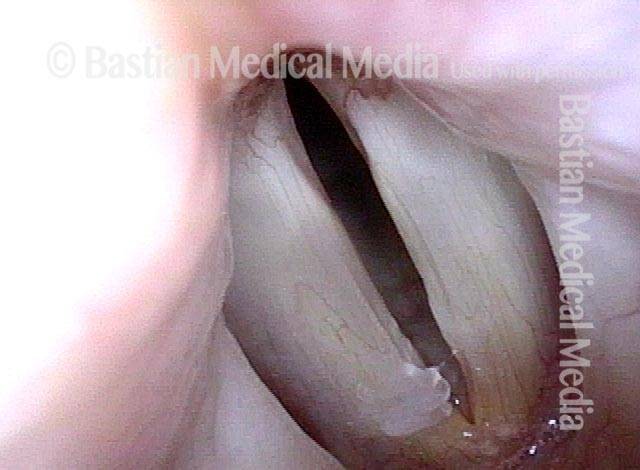

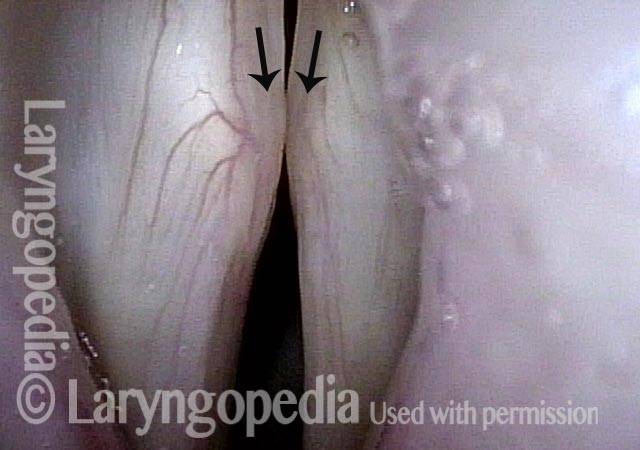

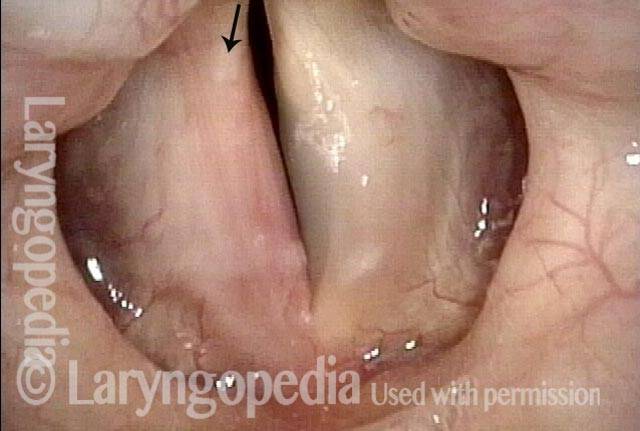

LCA paresis has recovered (4 of 4)

LCA paresis has recovered (4 of 4)

Bilateral LCA Weakness?

Weak, air-wasting voice (1 of 4)

Weak, air-wasting voice (1 of 4)

Pre-phonatory instant (2 of 4)

Pre-phonatory instant (2 of 4)

Phonatory blurring (3 of 4)

Phonatory blurring (3 of 4)

Bilateral LCA weakness (4 of 4)

Bilateral LCA weakness (4 of 4)

Severe MTD or Bilateral LCA Weakness?

Breathiness (1 of 6)

Breathiness (1 of 6)

Phonation (2 of 6)

Phonation (2 of 6)

Closed phase (3 of 6)

Closed phase (3 of 6)

Large gap (5 of 6)

Large gap (5 of 6)

Open phase (6 of 6)

Open phase (6 of 6)

Paresis Visual Taxonomy Can Be Trusted, But Is This Taking the LCA Cue Too Far?

Post carotid endarterectomy (1 of 7)

Post carotid endarterectomy (1 of 7)

PCA muscle (2 of 7)

PCA muscle (2 of 7)

Maximum closure (3 of 7)

Maximum closure (3 of 7)

Open phase (4 of 7)

Open phase (4 of 7)

LCA muscle (5 of 7)

LCA muscle (5 of 7)

Voice gel injection (6 of 7)

Voice gel injection (6 of 7)

Phonation (7 of 7)

Phonation (7 of 7)

Evolution of the Wound After Laser Removal of a Vocal Cord Cancer: Not Pretty at First, but Voice Result Can Be Very Good

Vocal cord cancer (1 of 8)

Vocal cord cancer (1 of 8)

Voice-making with tumor (2 of 8)

Voice-making with tumor (2 of 8)

One week post-removal (3 of 8)

One week post-removal (3 of 8)

Voice-making, post-removal (4 of 8)

Voice-making, post-removal (4 of 8)

Six weeks post-op (5 of 8)

Six weeks post-op (5 of 8)

Voice-making, post-op (6 of 8)

Voice-making, post-op (6 of 8)

Four months post-op (7 of 8)

Four months post-op (7 of 8)

Voice-making, four months post-op (8 of 8)

Voice-making, four months post-op (8 of 8)

Other variants of

vocal cord paresis:

TA-only (thyroarytenoid muscle)

PCA-only (posterior cricoarytenoid muscle)

IA-only (interaryteonid muscle)