Voice Building

Voice building is the process of adding strength to the voice by using a variety of tasks that tax its strength capabilities. The idea is that over time the larynx will rise to the challenge and adapt to increased demands, much as might happen to the arms as a result of a weight-lifting regimen.

Sometimes the voice building regimen is very simple and “do-it-yourself”; other times it is more sophisticated and requires the assistance of a speech pathologist who is singing voice qualified.

Begin with 30 seconds of the following 3 exercises (90 sec. in total):

Voice of Authority

Read a magazine, count out loud, or recite something you have memorized in a loud, low-pitched, “angry” chest voice.

SHIP AHOY! Voice

Read or recite as though calling at a higher pitch across the street to warn a neighbor about to step in a hole. “Hey, neighbor!!! Look out!!!

The Siren

Go from lowest chest voice to highest falsetto and back down, on a loud “Ooooooooh!!!”

Voice Building Tips

- While “bellowing” the three tasks above, imagine that you are “the Incredible Hulk;” ask family or friend to evaluate your performance.

- You and others may note that the voice you produce is weak (due to the under- lying disorder), but it is the effort that must be high and “convincing.”

- Try to complete 4 to 6 sessions of 90 seconds to 2 minutes per day. Do this while showering, driving to and from work, in the basement, etc. If necessary, bury your face in a pillow to muffle the sound.

The grand total of the several sessions: ~10 minutes per day.

What to Expect?

Voice may seem weaker immediately after aggressive voice use. Your arms would be too, in the first hour after lifting heavy weights. But muscles adapt / strengthen over time to persistent challenge.

Evaluate initial response to voice building after two weeks (at least 56 of these 90-second sessions). If there is improvement, keep up this strategy at least twice a day.

You might discover that there is more voice to call upon, or that voice fatigues less—or it “fades” later in the day than before. If you achieve an insufficient response, ask your doctor if injected or surgically placed implants could help.

How does voice building work?

Muscles get stronger when challenged. The bulging muscles of bodybuilders illustrate this. Muscles that produce voice (vocal cords, abdomen, etc.) can also be built up.

Without conscious intent, persons with boisterous, sociable personalities develop strong vocal tract muscles in the course of expressing that type of personality. Even the person who is quiet by nature but required to talk in a noisy workplace might develop a strong voice, by competing with background noise. Not to mention one kind of vocal “bodybuilder”: the opera singer.

On the other hand, persons who use their voices gently, or very little, or both, may have weaker voices that are hard for others to hear. Maybe they are introverted, live alone, or their job requires little talking.

Also consider persons who have a medical status or condition that tends to weaken the voice: Advanced age, frailty, life-threatening illness, Parkinson’s Disease, etc.

Persons evaluated medically for a fuzzy or husky voice that fades with use may be found to havebowed, atrophic, or flaccid, vocal cords.

If so, voice building may be able to help. In a perfect world, this would be under the supervision of a speech pathologist or voice coach.

Still, there is a do-it-yourself strategy you can pursue, at least initially, without fear of injury, if work with a professional is not possible or if a first appointment is delayed.

Does voice building change pitch?

A stronger voice often also sounds richer and this translates to “deeper” without necessarily a change in pitch. Low voice tends to become stronger, though.

Does voice building work for vocal fold paralysis?

Of course a paralyzed cord cannot be strengthened. The functioning side could be, and that might help marginally. It can’t hurt to try these but if the improvement is other than very modest, it might be due to some recovery on the paralyzed side.

Is there a such a thing as too aggressive in voice building?

Technically, yes, but limiting voice building to a minute or two per session would make it EXTREMELY unlikely. Especially if you do what is described. You are calling vigorously across the street; speaking in a loud “arguing” voice, and doing a loud siren. You aren’t screaming …

Can voice building help with vocal nodules?

Nodules are usually the result of “spending too much vocal money.” Often associated with a hearty, talkative personality, or heavy voice demands of work. Nodules are treated initially with managing the amount, manner, and spacing of voice use, often with the help of a speech pathologist.

And if nodules refuse to go away (are otherwise irreversible), then vocal cord microsurgery. The issue for voice building is often the opposite. The person who uses the voice little, or always very gently…

I am shy and projecting my voice is difficult. What should I do?

You are not alone in being unfamiliar/uncomfortable with the “big” voice that is available to you. I think you would find it enjoyable to take some voice lessons where exploring your voice is “safe.” Or try the basement or in your car. And maybe read the book “Quiet” to better understand your introversion.

Knowing one’s self (introversion) and the expanded capabilities of one’s voice can be rewarding so consider stepping outside your comfort zone!

Vocal Cord Paresis (Thyroarytenoid Muscle) Accentuated by Disuse

This woman illustrates that vocal cords are inhabited by muscle (thyroarytenoid muscle, to be precise). If that muscle atrophies due to paresis (partial loss of nerve supply), this alone can weaken the voice.

That is what happened to her 10 years ago, in her fifties, after thyroid surgery. Initially the left cord did not move (paralysis). Then movement returned and along with it, her voice gradually gained in strength.

When recovery was maximal, the vocal cord abducted (opened) and adducted (closed) normally. She also regained “90%” of her voice; while the muscle within the vocal cord did not recover fully, there was sufficient strength and tone to mostly “keep up” with the demands of her moderate voice use.

Technically, she began with paralysis (of TA, LCA, and PCA) but after recovery, had a TA-only paresis as shown in photos 1-3 below. All was well for 10 years as she had a perfectly functional voice.

Ten years later, now in her sixties, she developed a bad URI (not Covid-19) and voice deteriorated in the midst of hard bouts of coughing. At the same time, due to retirement, and self-quarantine, she was using voice very little.

Two months later, still using voice very little and even intentionally “resting it,” her voice is extremely weak. The explanation is that by figuratively putting her voice in bed, she has added disuse atrophy to the longstanding paresis. How do we know this? The answer is in photos 4-5 below. And the appropriate initial treatment? Voice building exercises.

Conus bulge in the larynx (1 of 5)

Conus bulge in the larynx (1 of 5)

Left vocal cord adducts normally (2 of 5)

Left vocal cord adducts normally (2 of 5)

Voice remains strong despite atrophy (3 of 5)

Voice remains strong despite atrophy (3 of 5)

Smaller conus bulge (4 of 5)

Smaller conus bulge (4 of 5)

Atrophy + Flaccidity (5 of 5)

Atrophy + Flaccidity (5 of 5)

Share this article

3 Simple Exercises to Strengthen A Weak Voice

A weak voice that can’t be heard in noisy places, or that “fades” in quality and strength across a day can be frustrating!

There is a long list of potential explanations. A common one is weak, atrophied, flaccid vocal cord—and other vocal tract—muscles. When this is the cause for a weak voice determined by medical evaluation, voice building is the first place to start.

In this video, Dr. Bastian provides background information about muscle building in general, and why vocal muscles can weaken in some people.

Voice Building Exercises

Voice Building Exercises

6 Voice Mufflers to Assist with Voice Building Exercises

Can you train your voice loudly without scaring the neighbors? In my last video, I shared a simple (and loud) way to build a weak voice. But what if someone’s in the next room?

This time, I test five “voice mufflers” marketed for quiet vocal practice—plus the original pillow method. No endorsements here—just a fun comparison with decibel readings. Watch and see which one keeps the peace!

7 Communication Tips for Those with A Weak Voice

(Especially If the Listener Is Hearing Impaired)

The combination of a weak voice in one person and weak “ears” in another can annoy, frustrate, and seriously hamper communication. Hearing aids and “voice building” can be a partial answer. And here are additional tips and pointers that may help two people struggling to communicate:

- Get listener’s attention

- Provide context—a “headline”

- Consider word choice with fewer fricatives/sibilants

- Use duplicate words

- Be aware of loudness setpoint

- O-Ver-ar-Ti-Cu-LaTe!

- Lip read

Loss of Upper Voice Caused by Lowered Muscular Ceiling (MTD)

Every voice has a natural range (from its “floor” to its “ceiling”), often 2 ½ octaves or more. Over time, some singers notice upper range loss or effortfulness (the ceiling descends). Yet there are no nodules or polyps.

When the “muscular ceiling” descends, it feels and sounds like the voice has to be pushed up to its upper range and the throat may almost ache with the effort. And pitch may sag. A common association in women is menopause, but it can be seen in either sex at any age.

Vocal Money – Recovering from Vocal Cord Injury

Individuals who develop chronic vibratory injuries of the vocal cords, such as nodules and polyps, can be thought of as having been vocal overspenders.

And so, conceptualizing voice use as spending vocal money can provide a helpful analogy for those rehabilitating from their injuries. The idea is to think of having vocal money to spend every day, and to manage the amount, manner, and spacing of expenditure, in order to get out of the vocal debt of vibratory injury.

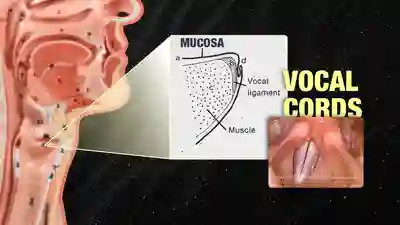

5 Symptoms of Vocal Cord Mucosal Injury

Singers or others who have injured the mucosa—surface layer—of their vocal cords may have normal-sounding speaking voices and at the same time, singing voice frustrations.

This video explains the 5 most common symptoms of injury. In addition, Dr. Bastian’s prior video on vocal cord swelling checks can help the singer know when to begin thinking “my problem may be injury, and not acid reflux or a technical deficit.”