Asymmetrical Vocal Cord Movement

There is a group of people whose vocal cords both move through a full range of motion, but they do not move in tandem. Think, by analogy, of a person whose eyelids both open and close fully, but just not at precisely the same time. You wouldn’t be able to say either eyelid was paralyzed or paretic (weak). You would just say they don’t move in tandem.

Vocal cords should also move as mirror images, at the same moment and with the same displacement from lateral to medial or medial to lateral.

What is the Cause of Asymmetrical Movement?

Obviously, vocal cord paresis or paralysis will produce asymmetrical movement. But asymmetrical movement is not the only finding: there will also be a difference of range of motion, vocal cord morphology (ventricle, margin, or conus fullness), or difference of vibratory amplitude.

There are additional circumstances where asymmetrical vocal cord movement as an isolated finding, in circumstances where morphology, range of motion, and vibratory amplitude (viewed under strobe light), are all equivalent. Note that one must be very good at seeing TA-only, TA + LCA, PCA-only, LCA-only, and IA-only paresis before one can say definitively, “the issue here is only asymmetry of movement.

Is There A Diagnosis for Asymmetrical Movement?

How do we best see asymmetrical vocal cord movement? Usually during quiet breathing. (Movements during gagging, irritative coughing, or laryngospasm can be asymmetrical and “don’t count.”) In the (typically) small movements of the vocal cords during quiet respiration, we note that one vocal cord lags the other consistently. Or it may lag during one inspiratory/expiratory cycle, and lead in the next. Or one or the other might “jump” or “twitch.”

Where is Asymmetrical Movement most Often Seen?

Several disorders come to mind, though there may be others:

1) Vocal cord paresis or paralysis, and in this case asymmetry of movement is less important than morphological, range of motion, or vibratory amplitude differences between the two cords.

2) Laryngeal dystonia (most often expressed as spasmodic dysphonia). In this case, the vocal phenomenology often carries the main diagnostic importance, and asymmetrical vocal cord movement is an unsurprising finding without a lot of diagnostic import.

3) Sensory neuropathic cough (SNC) – as a possible motor manifestation of the (otherwise) primarily sensory neuropathy. Here, the history leads the way in making the diagnosis; asymmetrical vocal cord movement is seen in maybe a third of cases of SNC, and is an intriguing supportive, but non-diagnostic finding.

4) Other neurological disorders such as neuromuscular disorder.

Conclusion

Although mostly answered above, does asymmetrical vocal cord movement support any diagnosis of its own? Not often in our experience. Usually after applying the integrative diagnostic model, the diagnosis of paresis or paralysis, laryngeal dystonia, sensory neuropathic cough, or a global neurological disorder such as ALS will be obvious.

Arytenoid Mismatch makes for Gravelly Voice Quality is Hard to fix in Some Cases of Vocal Cord Paralysis

Arytenoids do not align (1 of 5)

Arytenoids do not align (1 of 5)

Vocal processes (2 of 5)

Vocal processes (2 of 5)

Vocal processes do not match when touching (3 of 5)

Vocal processes do not match when touching (3 of 5)

Vocal cords out of alignment (4 of 5)

Vocal cords out of alignment (4 of 5)

Asymmetrical vibration (5 of 5)

Asymmetrical vibration (5 of 5)

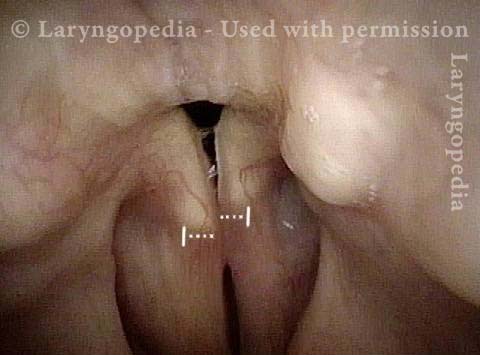

Asymmetrical Vocal Cord Movement

This person manifests noticeably asymmetrical vocal cord movement. Her diagnosis happens to be sensory neuropathic cough (SNC).