Contact Granuloma

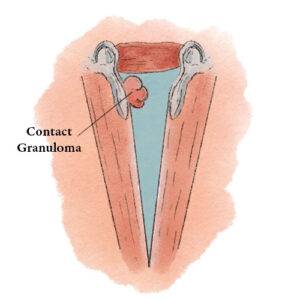

A contact granuloma is a benign tissue reaction or growth, typically on the posterior third of the vocal cord, that occurs in response to injury. They are also known as contact ulcers, intubation granulomas, or “proud flesh.” This kind of chronically irritated tissue may be viewed as an exuberant healing response that “didn’t know when to quit.”

Sources of Injury

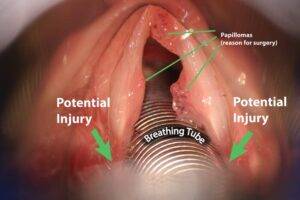

One type of injury that may lead to a contact granuloma is injury from an endotracheal tube, as the inserted tube presses and rubs against the posterior ends of the vocal cords.

Another potential source of injury is chronic, aggressive coughing or throat-clearing. Yet another potential source is undergoing surgical procedures such as laser excision of a cancer. Some also believe that irritation from acid reflux can lead to a contact granuloma. In many cases, there is no obvious cause for the original injury.

Typical Location

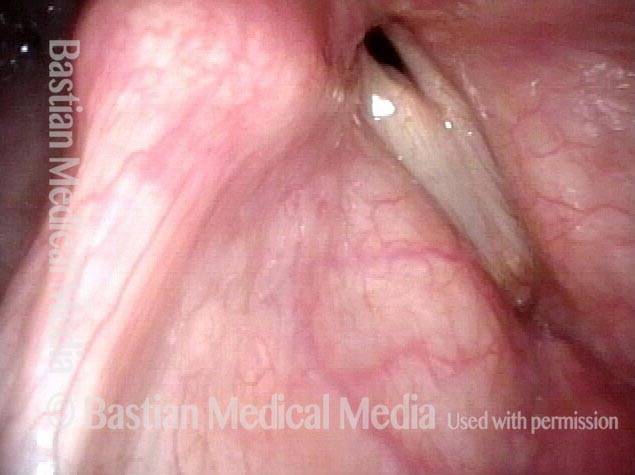

Contact granulomas typically occur on the posterior third of the vocal cord, also known as the cartilaginous glottis. Unlike the other two-thirds of the vocal cord, this segment is inhabited by cartilage (namely, the arytenoid cartilage), and that cartilage is covered only by a relatively thin layer of perichondrium and a layer of mucosa. This thinly cushioned cartilage or perichondrium interface is particularly prone to being irritated and then responding with the exaggerated healing that produces a contact granuloma. Hence, most granulomas occur in this location.

Contact granulomas typically occur on the posterior third of the vocal cord, also known as the cartilaginous glottis. Unlike the other two-thirds of the vocal cord, this segment is inhabited by cartilage (namely, the arytenoid cartilage), and that cartilage is covered only by a relatively thin layer of perichondrium and a layer of mucosa. This thinly cushioned cartilage or perichondrium interface is particularly prone to being irritated and then responding with the exaggerated healing that produces a contact granuloma. Hence, most granulomas occur in this location.

Symptoms

Some individuals with contact granulomas have no symptoms whatsoever and only discover they have a granuloma while being examined for some other reason. Others notice a sticking or pinprick sensation, or have some sense of vague discomfort in the area of the neck radiating upward towards the angle of the jaw.

Occasionally, a person may develop a “catch” in the voice, such that it takes a second to begin speaking clearly. Very occasionally, when a bit of the granuloma detaches (see below), a person may cough up blood or a tiny piece of tissue. In general, symptoms are mild.

Treatment

Some clinicians prefer to treat contact granulomas by removing them. However, the tiny injury or wound that results often produces a recurrent granuloma.

A better approach is simply to wait for the granuloma to detach of its own accord. This process of self-detachment, which may take several months, is like an apple maturing and then dropping from the tree: the granuloma continues to grow in size, and once it becomes big enough, the back-and-forth movement of air and the displacement caused by contact with the opposite arytenoid cartilage cause the granuloma to slowly pinch inward at its base and become more and more pedunculated. Eventually, the connecting stalk can no longer support the granuloma, and the granuloma breaks free. For an example, see the photos below.

If, however, a person’s symptoms are too troublesome to wait for months, then the granuloma can be surgically removed, but while still leaving part of the stalk or base projecting from the surface, so as to avoid re-injuring the cartilage and perichondrium, which would provoke the formation of another granuloma.

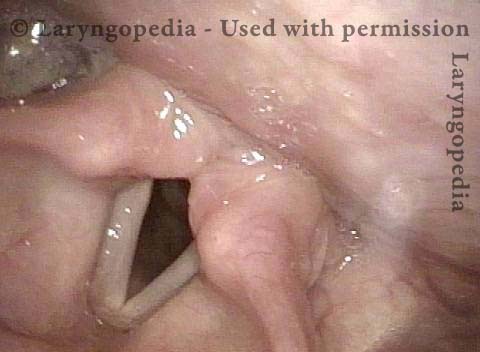

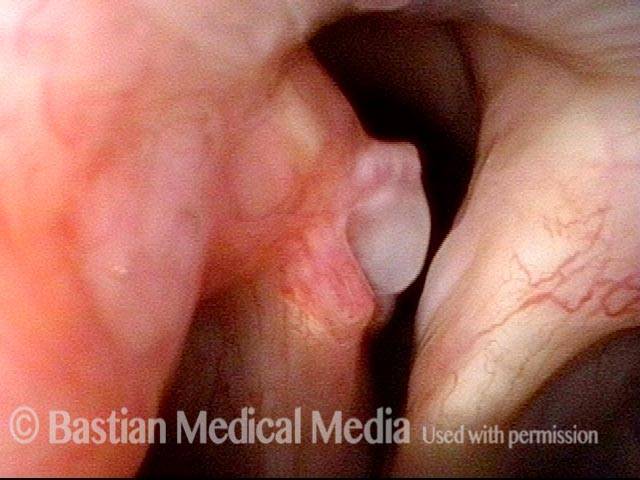

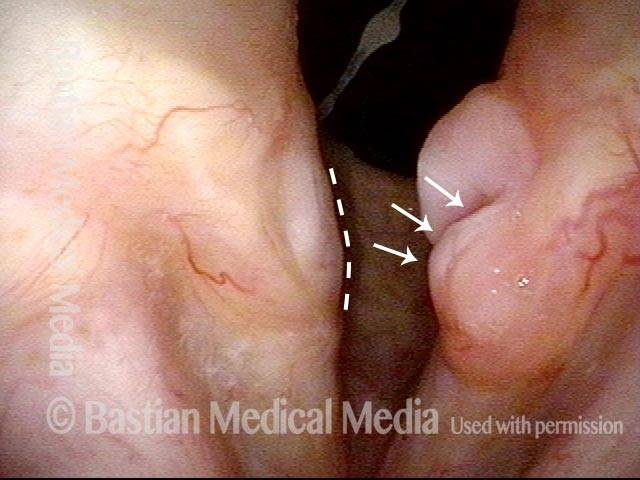

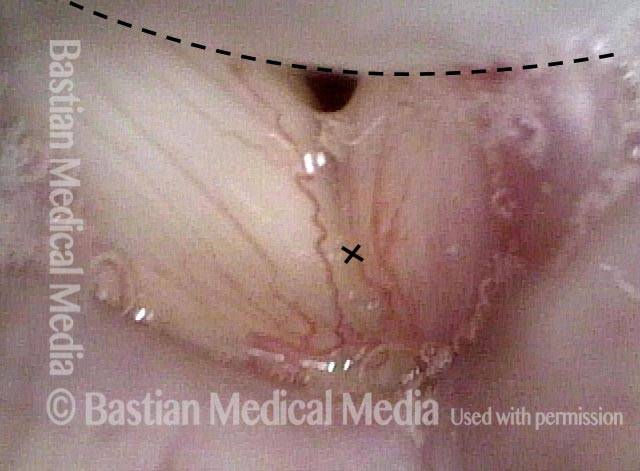

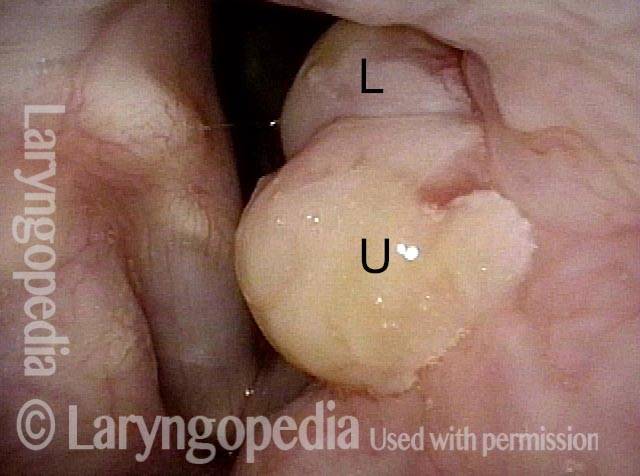

“Tongue and groove” Fit of a Bi-lobed Contact Granuloma

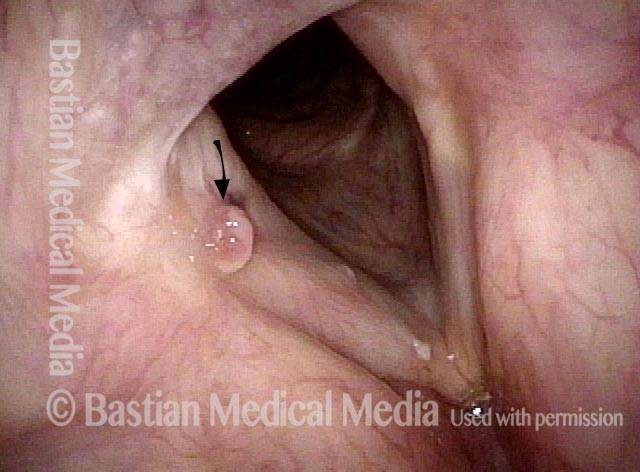

This man experiences momentary sharp pain when he first talks after an interval of silence. He has had a biopsy elsewhere but the lesion (a contact granuloma) has returned, as would be expected, due to re-injury of the arytenoid perichondrium.

As explained elsewhere, contact granulomas can be diagnosed by “certain” visual criteria, and be allowed to mature and detach spontaneously, with no need for removal except in unusual circumstances.

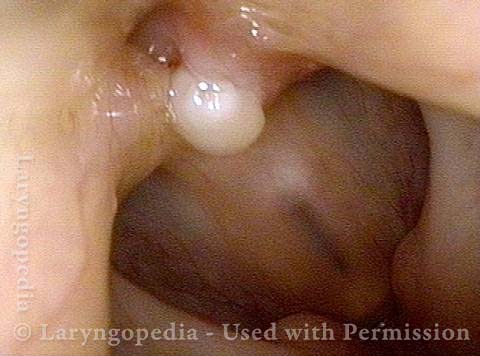

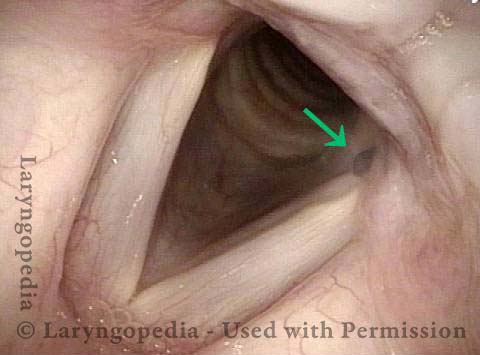

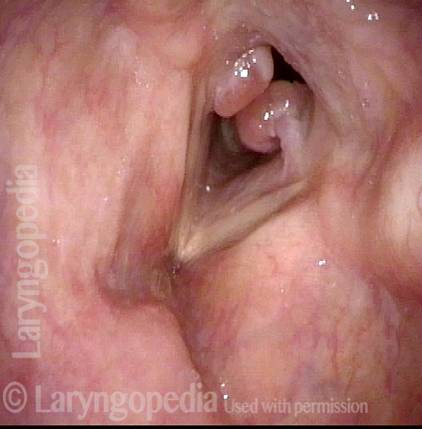

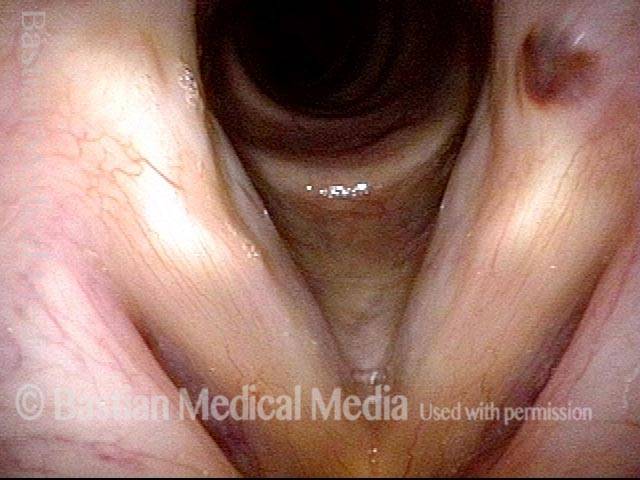

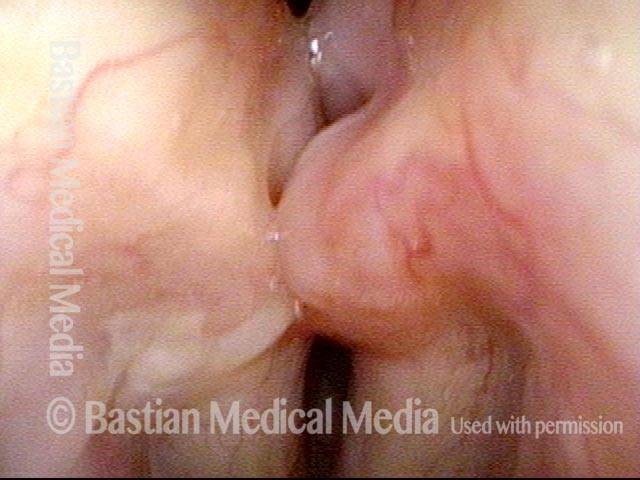

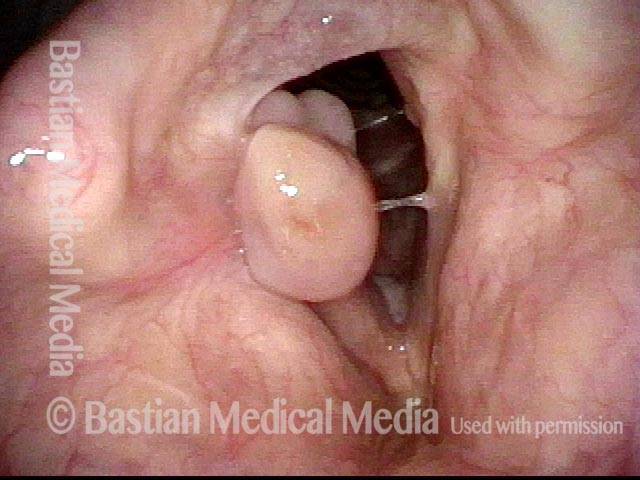

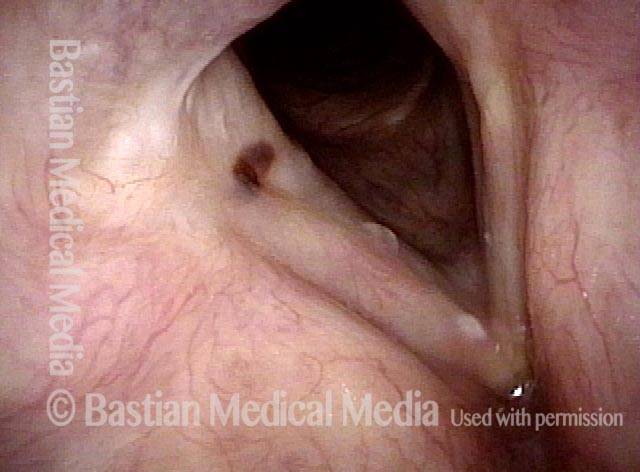

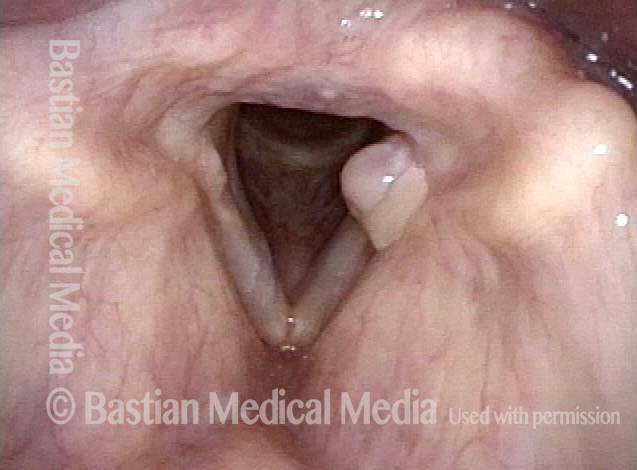

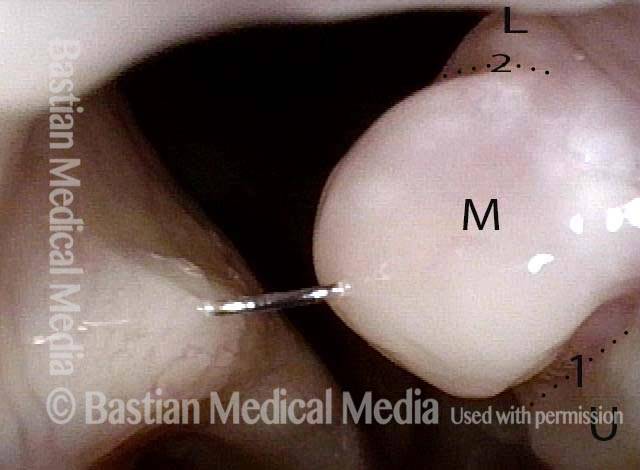

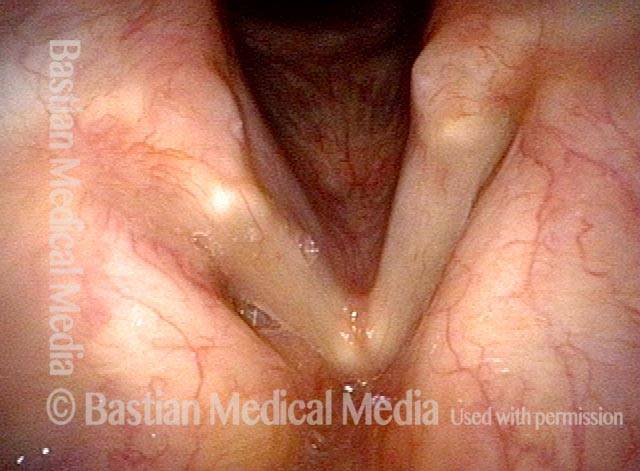

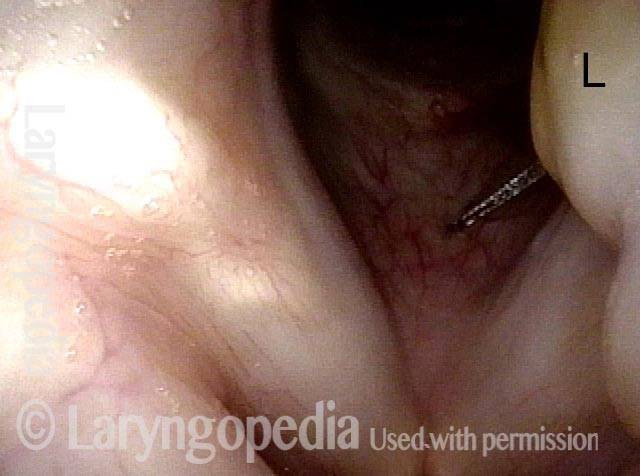

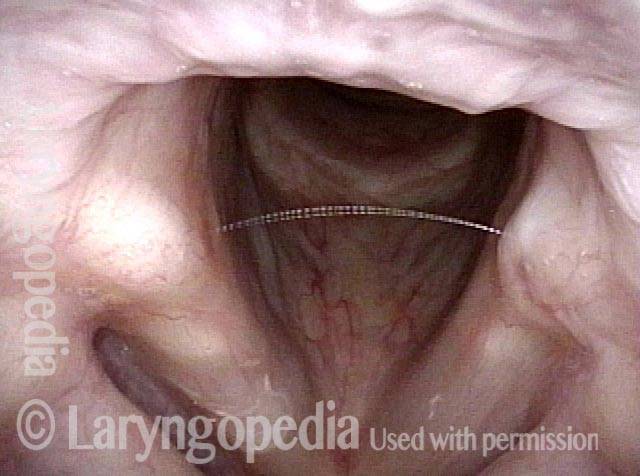

Tongue and groove (1 of 4)

Tongue and groove (1 of 4)

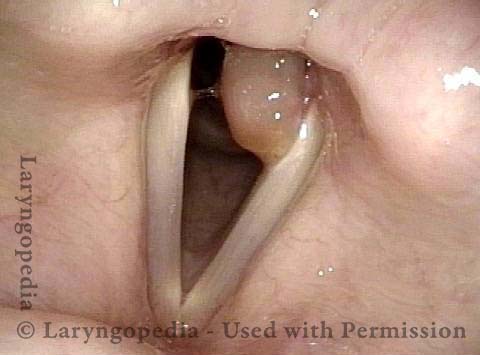

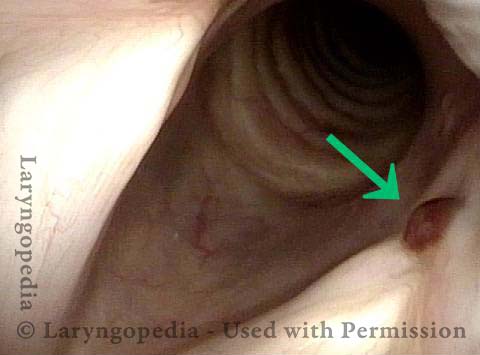

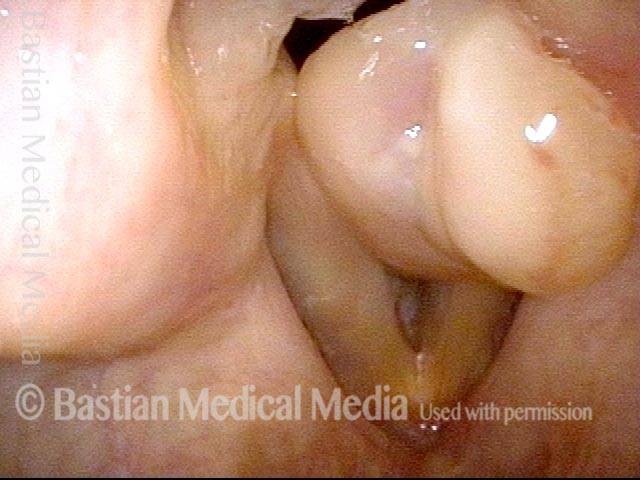

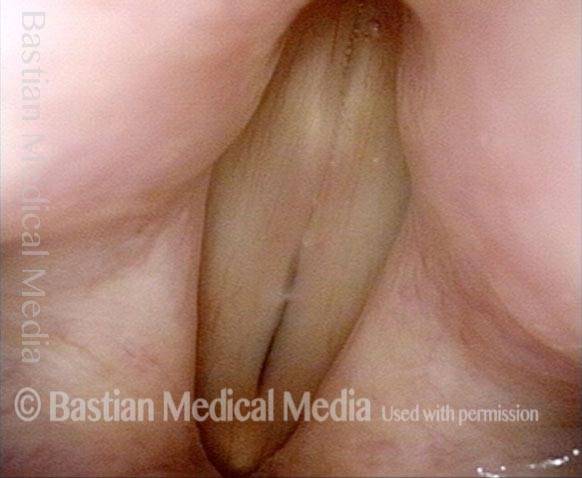

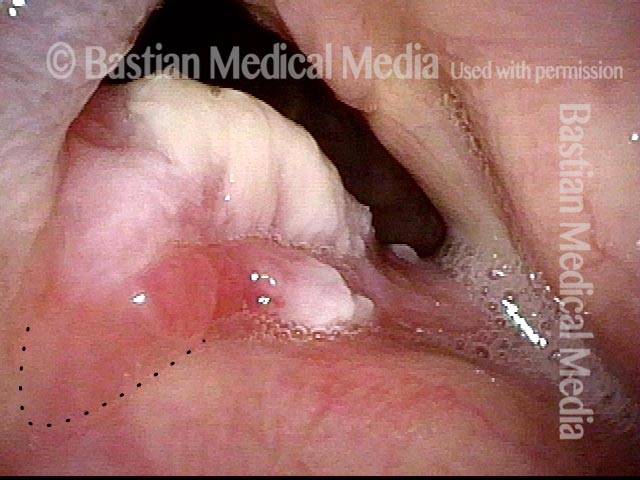

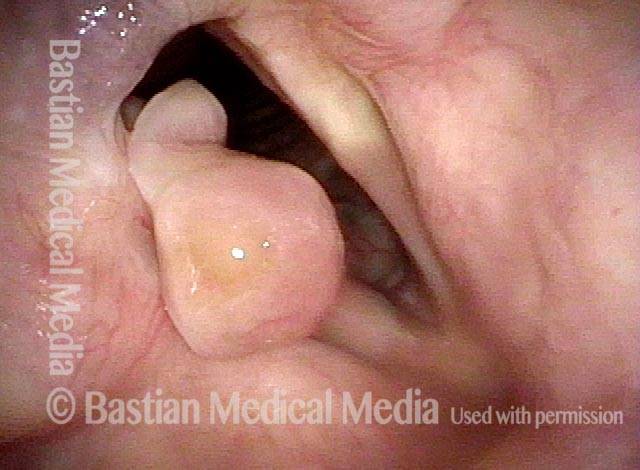

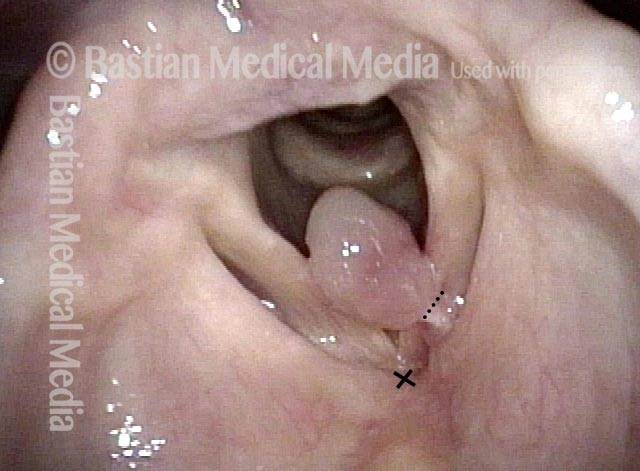

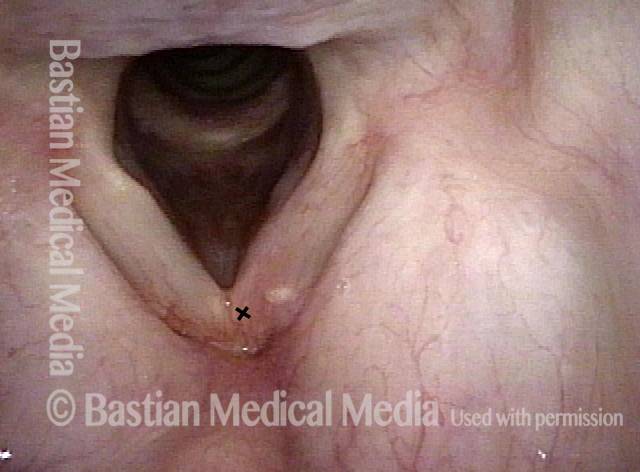

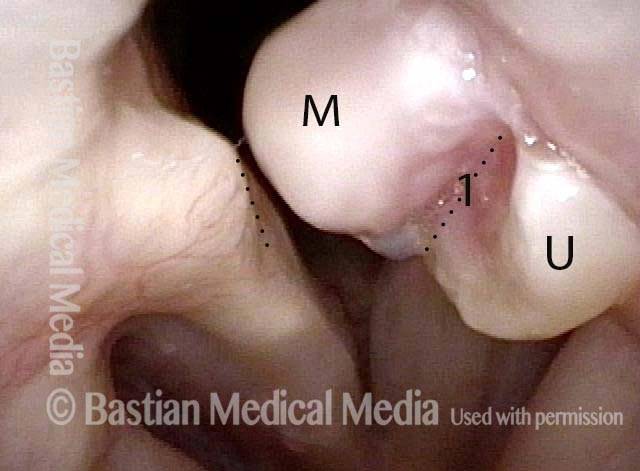

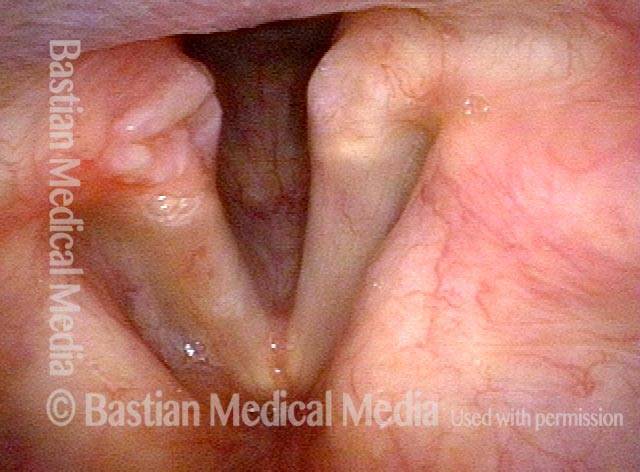

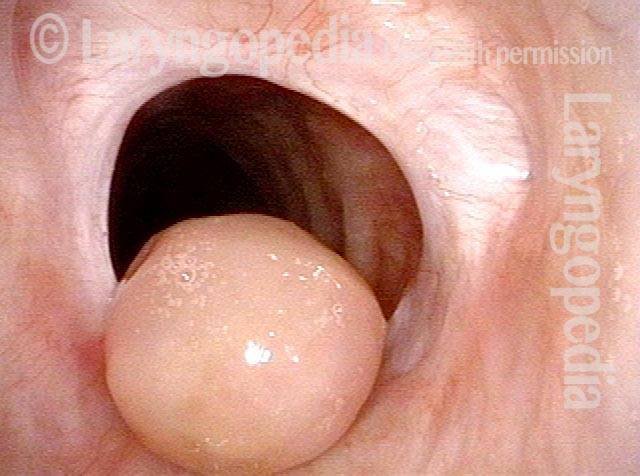

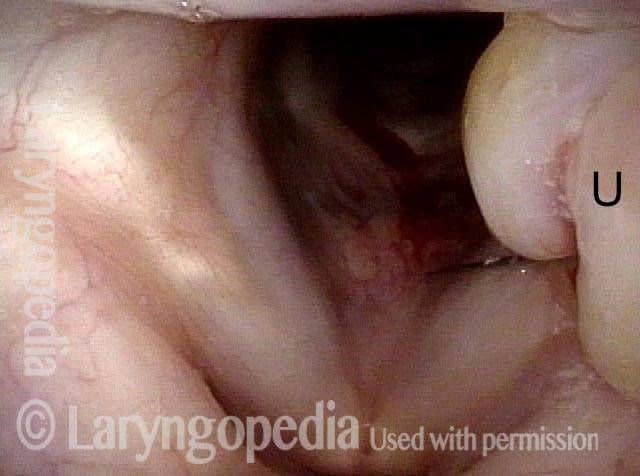

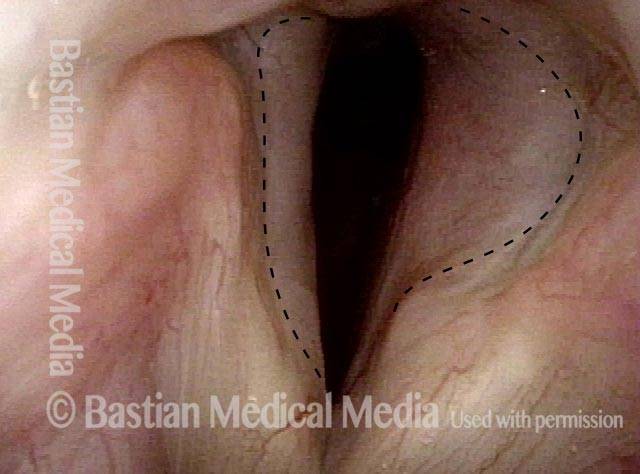

Bi-lobed lesion (2 of 4)

Bi-lobed lesion (2 of 4)

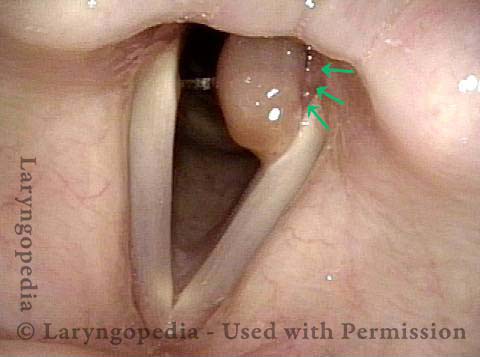

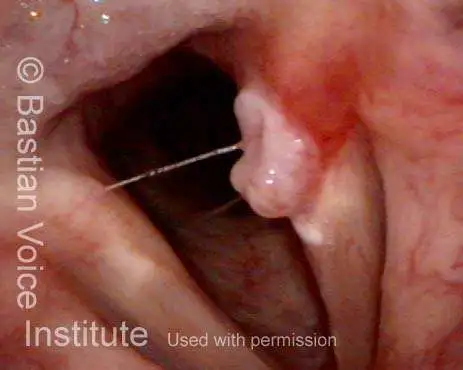

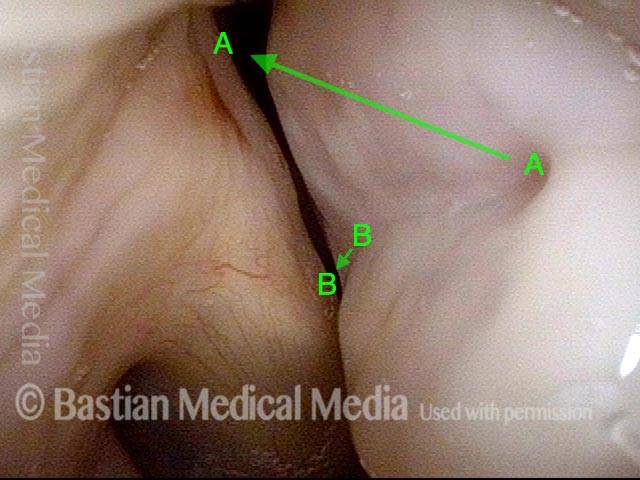

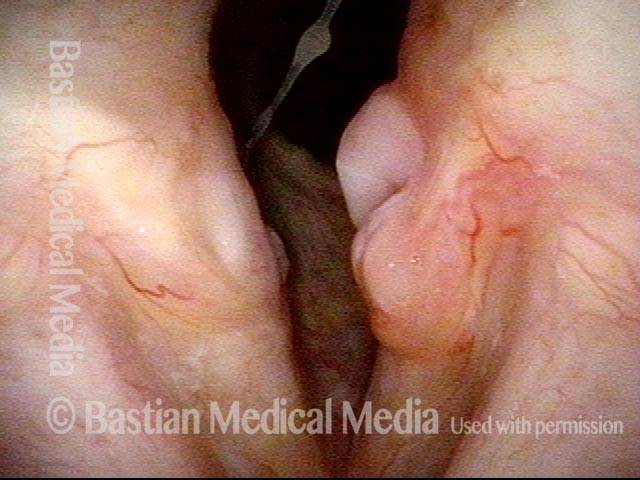

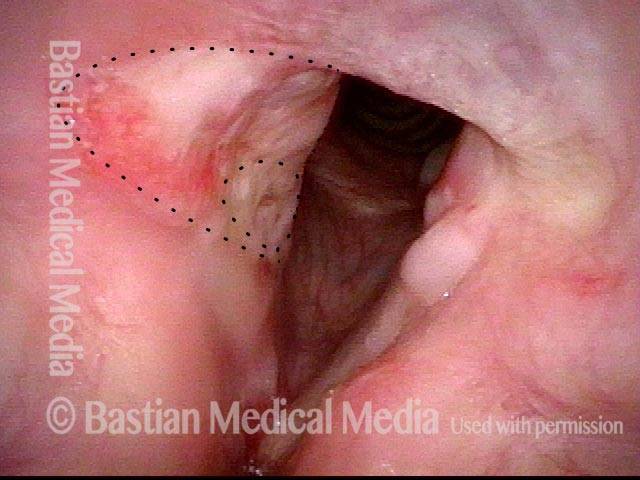

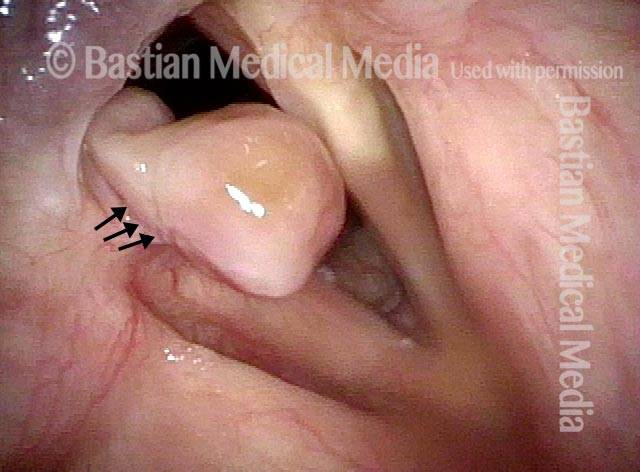

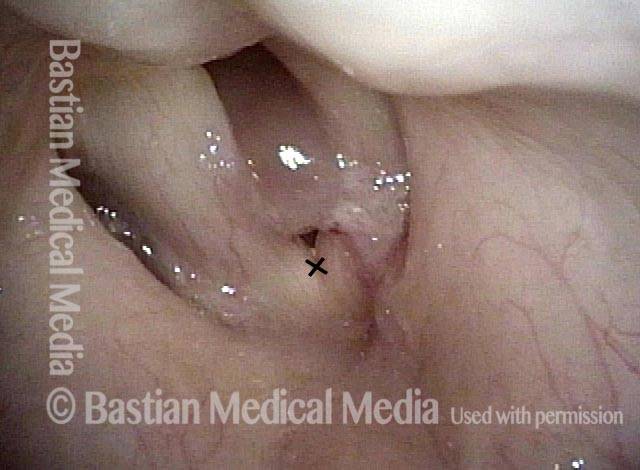

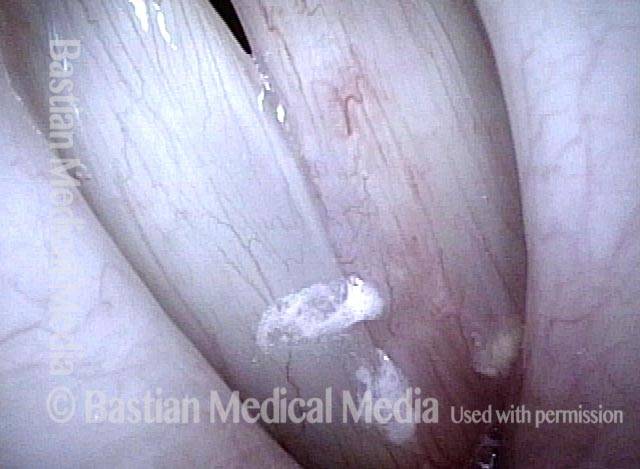

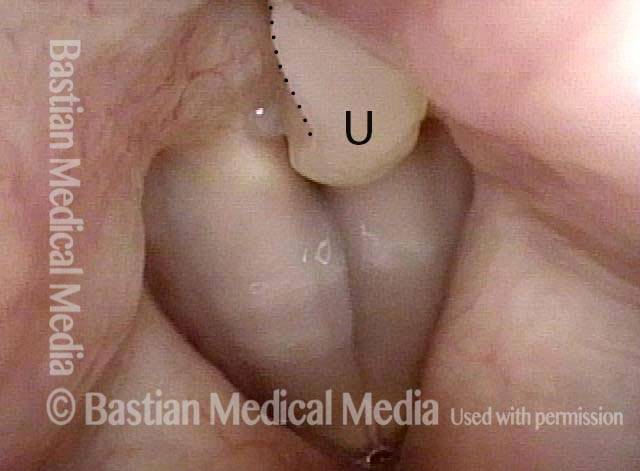

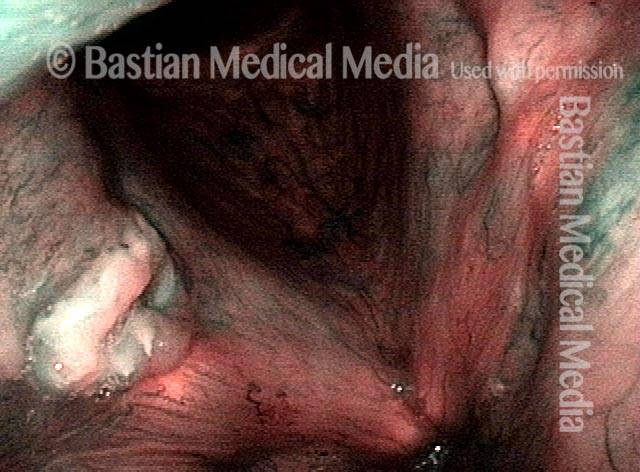

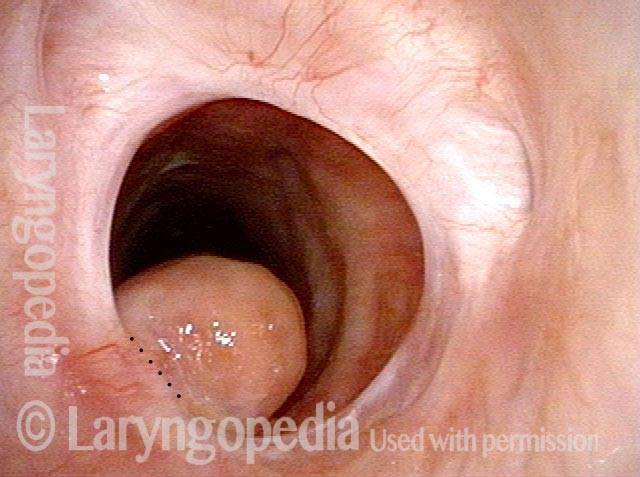

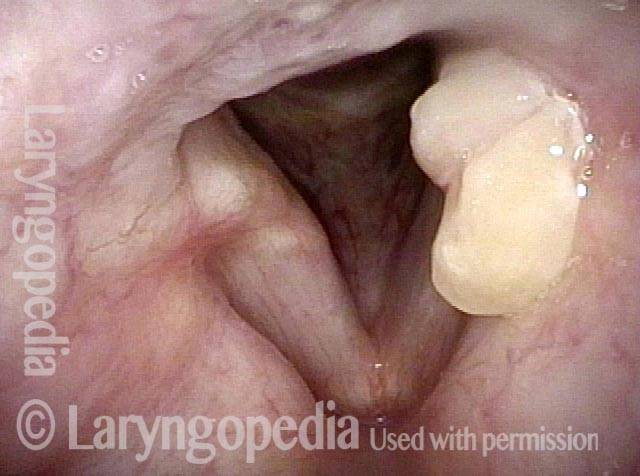

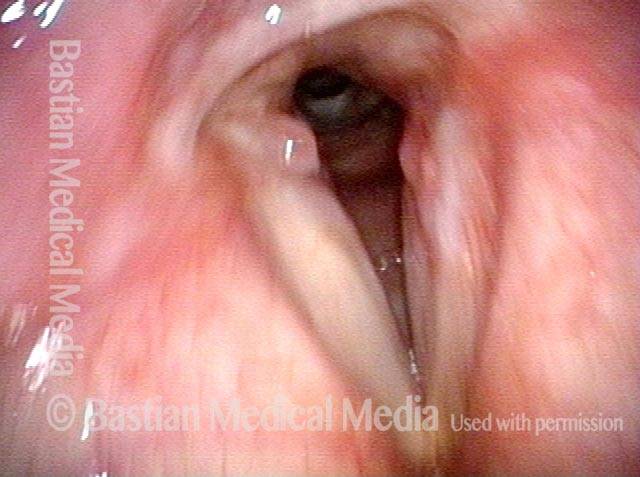

Bi-lobed morphology of granuloma (3 of 4)

Bi-lobed morphology of granuloma (3 of 4)

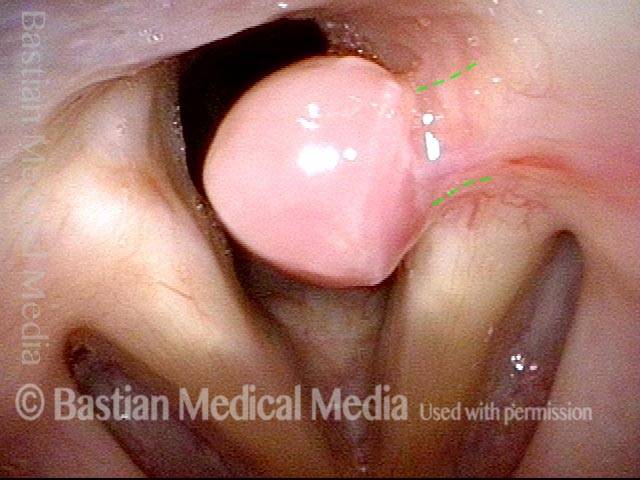

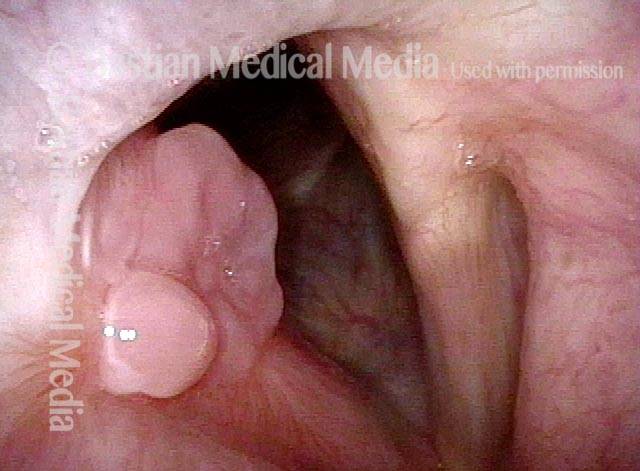

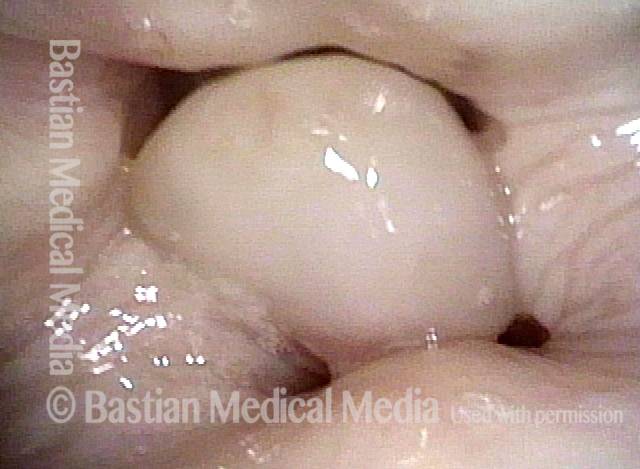

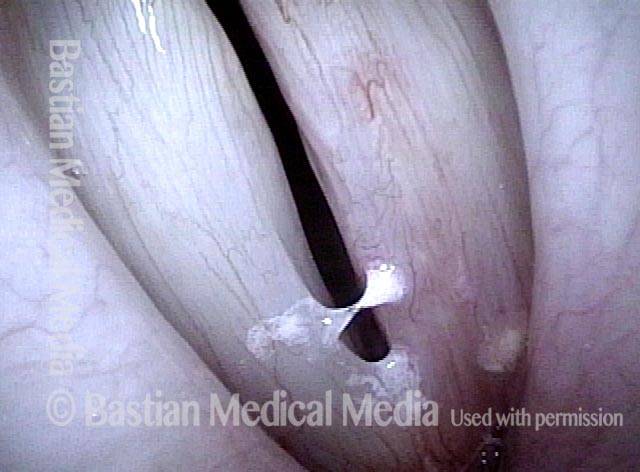

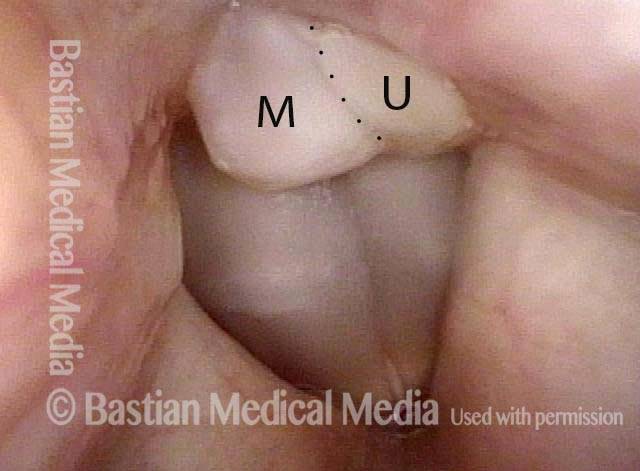

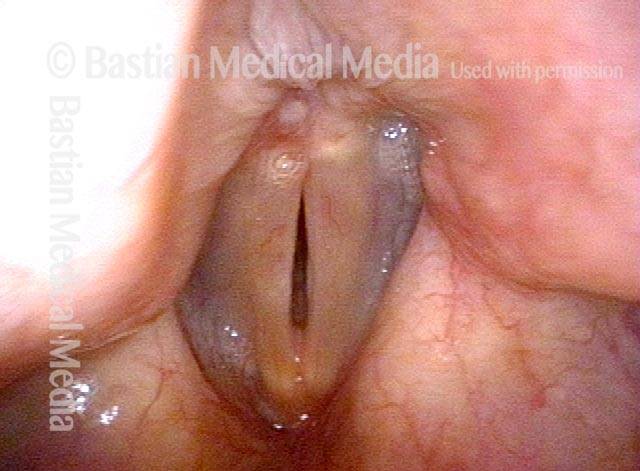

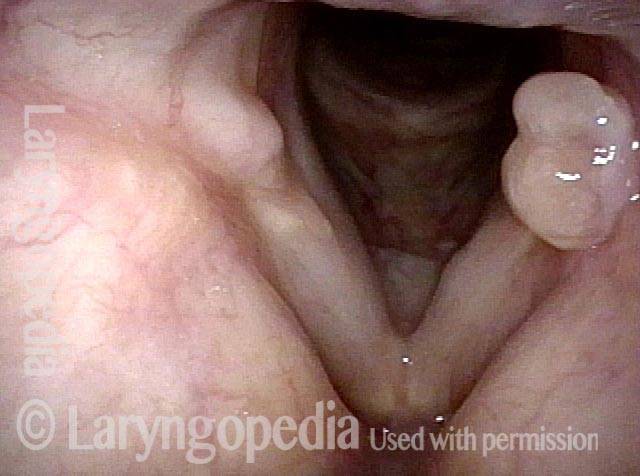

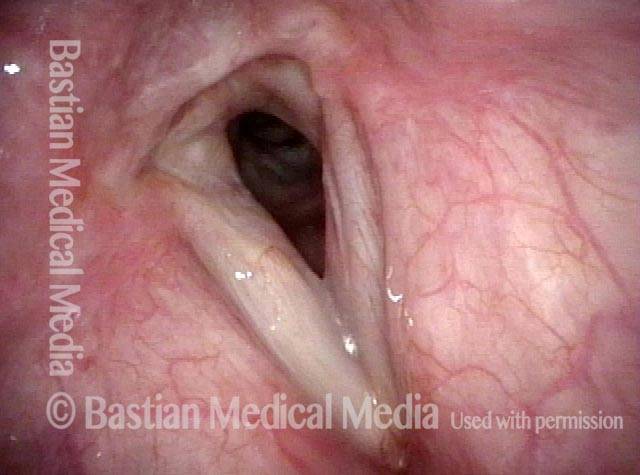

Tongue and groove fit between cords (4 of 4)

Tongue and groove fit between cords (4 of 4)

“Tattoo” of Blood after Detachment of Intubation Granuloma

Intubation granuloma (1 of 5)

Intubation granuloma (1 of 5)

Pedunculation in process (2 of 5)

Intubation granuloma (2 of 5)

Granuloma is gone (3 of 5)

Granuloma is gone (3 of 5)

Blood tattoo (4 of 5)

Blood tattoo (4 of 5)

Blood Tattoo (5 of 5)

Blood Tattoo (5 of 5)

Photo Essay of Contact Granuloma

Residual haziness (1 of 2)

Residual haziness (1 of 2)

Bi-lobed granuloma (2 of 2)

Bi-lobed granuloma (2 of 2)

Example 2

Bi-lobular Granuloma (1 of 2)

Bi-lobular Granuloma (1 of 2)

Arytenoid cartilage fits into cleft (2 of 2)

Arytenoid cartilage fits into cleft (2 of 2)

Intubation Granulomas Can Be Left Alone to Mature and Spontaneously Detach

Intubation Granuloma (1 of 3)

Intubation Granuloma (1 of 3)

Pedunculated Granuloma (2 of 3)

Pedunculated Granuloma (2 of 3)

Pedunculation in process (3 of 3)

Pedunculation in process (3 of 3)

Contact Granuloma, Gradually Pedunculating and then Detaching

Bi-lobed granuloma (1 of 11)

Bi-lobed granuloma (1 of 11)

Granuloma displaces upwards (2 of 11)

Granuloma displaces upwards (2 of 11)

Vocal process fits in granuloma cleft (3 of 11)

Vocal process fits in granuloma cleft (3 of 11)

Granuloma doesn’t affect voice (4 of 11)

Granuloma doesn’t affect voice (4 of 11)

2 months later (5 of 11)

2 months later (5 of 11)

Granuloma slowly penduculates (6 of 11)

Granuloma slowly penduculates (6 of 11)

2 months later (7 of 11)

2 months later (7 of 11)

Granuloma detached (8 of 11)

Granuloma detached (8 of 11)

One year later (10 of 11)

One year later (10 of 11)

Contact Granuloma, “Key-in-lock Fit”

Bi-lobed granuloma (1 of 3)

Bi-lobed granuloma (1 of 3)

Key-in-lock granuloma (2 of 3)

Key-in-lock granuloma (2 of 3)

Cleft and bi-lobularity (3 of 3)

Cleft and bi-lobularity (3 of 3)

The Healing Sequence of Granulation

Large tumor, before removal (1 of 8)

Large tumor, before removal (1 of 8)

After tumor removal (2 of 8)

After tumor removal (2 of 8)

2 months after surgery (3 of 8)

2 months after surgery (3 of 8)

5 Months after surgery, a granuloma is seen (4 of 8)

5 Months after surgery, a granuloma is seen (4 of 8)

7 months after surgery (5 of 8)

7 months after surgery (5 of 8)

Pedunculation (6 of 8)

Pedunculation (6 of 8)

One year after surgery (7 of 8)

One year after surgery (7 of 8)

15 months after surgery (8 of 8)

15 months after surgery (8 of 8)

Vocal Cord “Tear” and Granuloma

Intubation injury (1 of 8)

Intubation injury (1 of 8)

Granuloma drawn into glottis (2 of 8)

Granuloma drawn into glottis (2 of 8)

Phonation (3 of 8)

Phonation (3 of 8)

Anterior commissure (4 of 8)

Anterior commissure (4 of 8)

Granuloma detached (5 of 8)

Granuloma detached (5 of 8)

Vocal cord blurring (6 of 8)

Vocal cord blurring (6 of 8)

Closed phase (7 of 8)

Closed phase (7 of 8)

Open phase (8 of 8)

Open phase (8 of 8)

TRI-Lobed Contact Granuloma

Panoramic view (1 of 6)

Panoramic view (1 of 6)

Upper and middle lobule, cleft 1 (2 of 6)

Upper and middle lobule, cleft 1 (2 of 6)

Phonation (3 of 6)

Phonation (3 of 6)

Lower lobule (4 of 6)

Lower lobule (4 of 6)

Upper and middle lobule, Cleft 2 (5 of 6)

Upper and middle lobule, Cleft 2 (5 of 6)

Tri-lobed (6 of 6)

Tri-lobed (6 of 6)

Contact Granuloma—Ulcer Type With Rolled Border

Persistent granuloma (1 of 4)

Persistent granuloma (1 of 4)

Narrow band light (2 of 4)

Narrow band light (2 of 4)

Phonation (3 of 4)

Phonation (3 of 4)

One year later (4 of 4)

One year later (4 of 4)

Evolution of Circular Tracheal Scar Including Granuloma

Two weeks post-op (1 of 4)

Two weeks post-op (1 of 4)

Six weeks post-op (2 of 4)

Six weeks post-op (2 of 4)

Inhaling (3 of 4)

Inhaling (3 of 4)

Rapid inhalation (4 of 4)

Rapid inhalation (4 of 4)

Granulomas Mature and Fall Off by Themselves, But Steroid Injection Can Help…

“Third” granuloma (1 of 6)

“Third” granuloma (1 of 6)

Injection into lower lobe (2 of 6)

Injection into lower lobe (2 of 6)

Injection into upper lobe (3 of 6)

Injection into upper lobe (3 of 6)

Five weeks later (4 of 6)

Five weeks later (4 of 6)

Six months post-injection (5 of 6)

Six months post-injection (5 of 6)

One year post-injection (6 of 6)

One year post-injection (6 of 6)

Sometimes you DO Remove Granulation to Avoid Tracheotomy

Granulation (1 of 8)

Granulation (1 of 8)

Closer view (2 of 8)

Closer view (2 of 8)

Post microlaryngoscopies (3 of 8)

Post microlaryngoscopies (3 of 8)

Scarring (4 of 8)

Scarring (4 of 8)

Post posterior commissuroplasty (5 of 8)

Post posterior commissuroplasty (5 of 8)

Breathing improved (6 of 8)

Breathing improved (6 of 8)

Closer view (7 of 8)

Closer view (7 of 8)

Phonatory view (8 of 8)

Phonatory view (8 of 8)

Share this article

Audio Overview

Audio Overview

What are the common symptoms of granulomas?

- A sticking sensation and sometimes a vague awareness that radiates to the jaw and ear.

- Voice quality is not much affected because the back of the vocal fold does not vibrate for voice*.

* Occasionally voice is altered if the granuloma becomes very large and won’t let the front part come together fully to make voice.

What is does the recovery time for granulomas look like?

Normally the granuloma does have to heal over a long period of time—many months, and sometimes a year or more.

When a granuloma enlarges from one visit to the next in one of my patients, I usually say, somewhat counterintuitively, “way to go!” That’s because as the granuloma gets bigger it also typically pinches in at the base, a process we call pedunculation. When it flips back and forth and is quite mobile, it’s ready to fall off.

Occasionally the stalk is very fibrotic and once in a great while we remove the lesion. Most of the time, however, we just wait for it to mature as described above and then fall off.

I do not suggest voice rest, but only prudence, and refraining from loud, percussive voice and aggressive throat-clearing.