Vocal Cord Paralysis, Unilateral

Unilateral vocal cord paralysis is the neurogenic inability of one vocal cord to move. It is associated with weak voice of a degree that can vary between individuals.

See also: Vocal cord paralysis, bilateral, Vocal cord paresis.

What Causes Vocal Cord Paralysis?

If the recurrent laryngeal nerve gets damaged anywhere along the way from brainstem to larynx, then some or all of the vocal cord muscles might be weakened (paretic) or completely immobilized (paralyzed), thereby affecting the person’s voice or breathing.

Can the Nerve Recover on Its Own?

If the damaged nerve is still intact, then it may recover on its own, either completely or at least enough to meet the person’s vocal needs. This recovery can take up to a year because neural tissue heals much more slowly than skin or even bone.

Sometimes, though, the nerve does not recover, or not enough to meet the person’s vocal needs. There is no need to wait for a potential recovery if a tumor has invaded the nerve or if the nerve is known to be severed.

Vocal Cord Paralysis Defined by 3 Individual Muscles Denervated rather than as Recurrent Nerve Non-Function

Vocal cord paralysis is ordinarily defined as an immobile cord and thoughts go directly to recurrent nerve injury. The visual “definition” most universally used is loss of abduction (though there is also loss of medial compression). Said another way, we tend to think of the recurrent nerve being “out” but not so much of the three individual muscles that are denervated as a consequence. By contrast, paresis is defined by which one (or two) of the following muscles is/are denervated:

- Posterior cricoarytenoid (PCA)

- Lateral cricoarytenoid (LCA)

- Thyroarytenoid (TA)

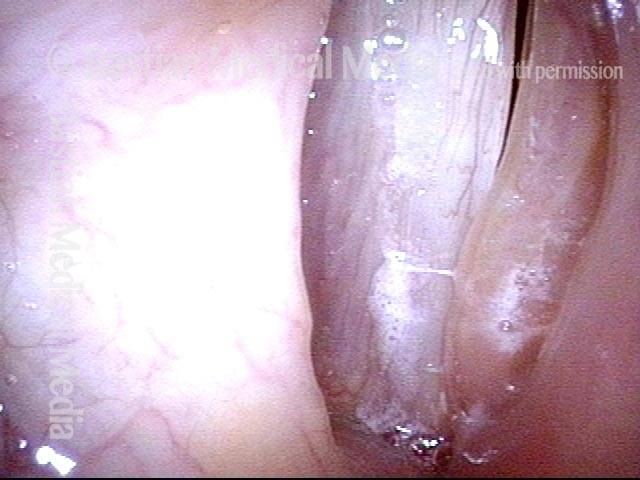

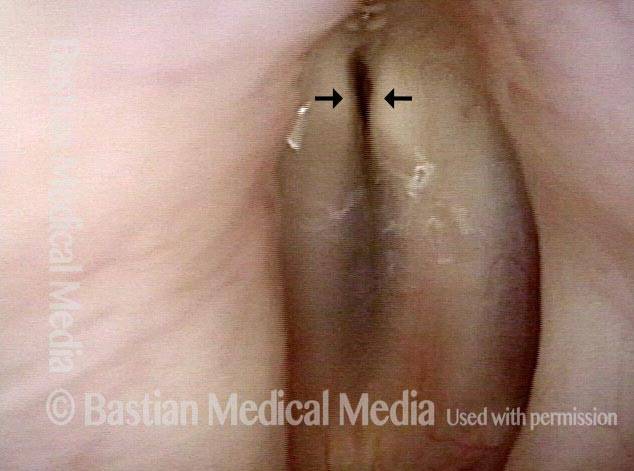

But returning to the term “paralysis,” it could be defined as denervation of all three muscles: PCA, LCA, and TA. This is shown clearly in the following set of images. Note that we typically leave out the interarytenoid (IA) muscle because it is bilaterally innervated and doesn’t often seem to figure in vocal cord paralysis.

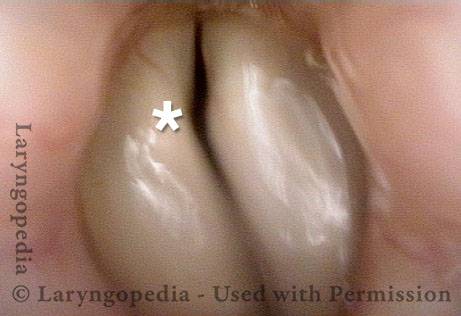

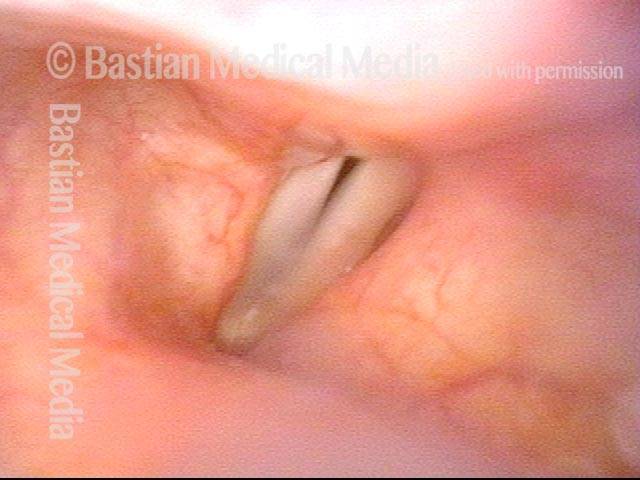

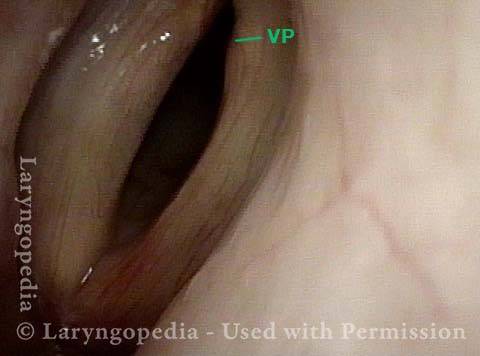

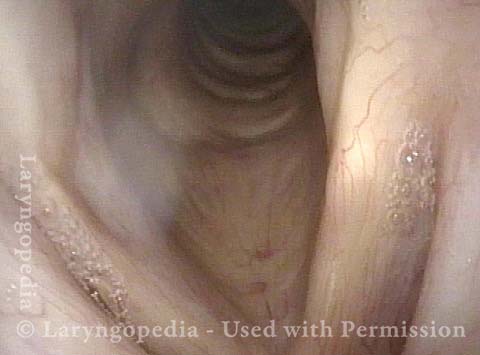

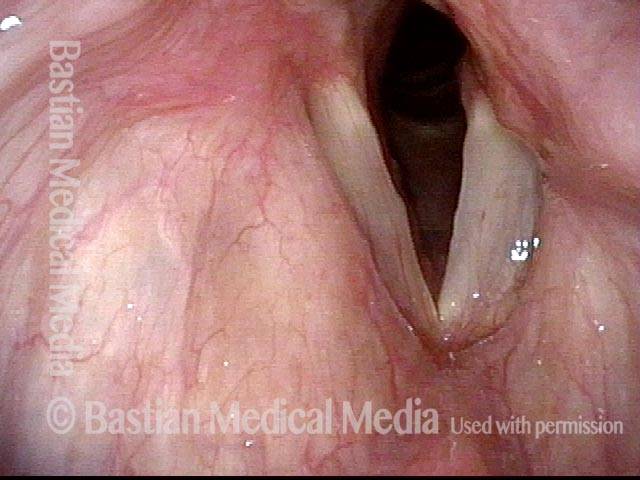

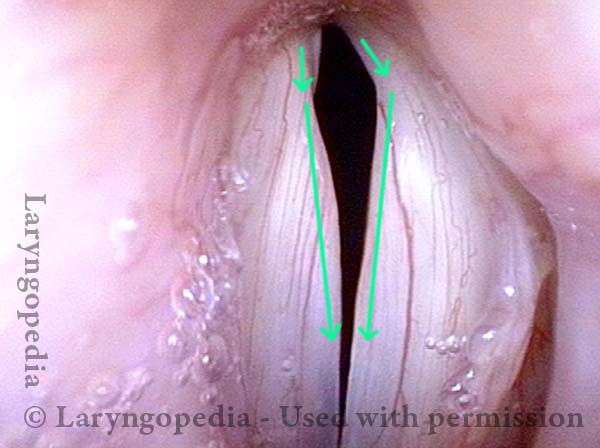

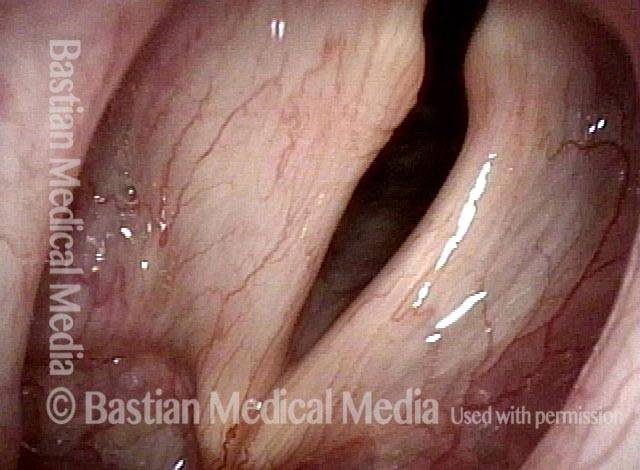

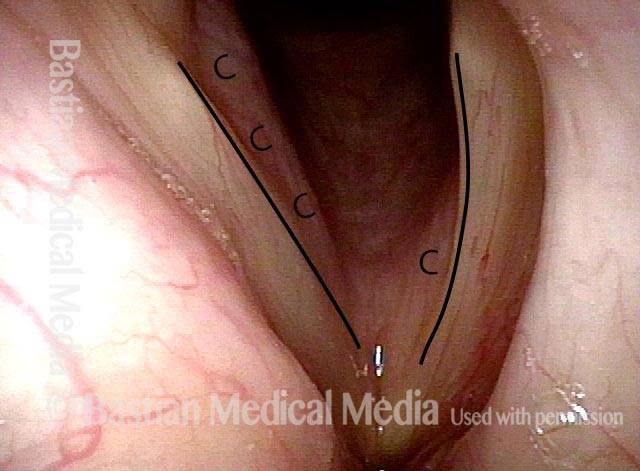

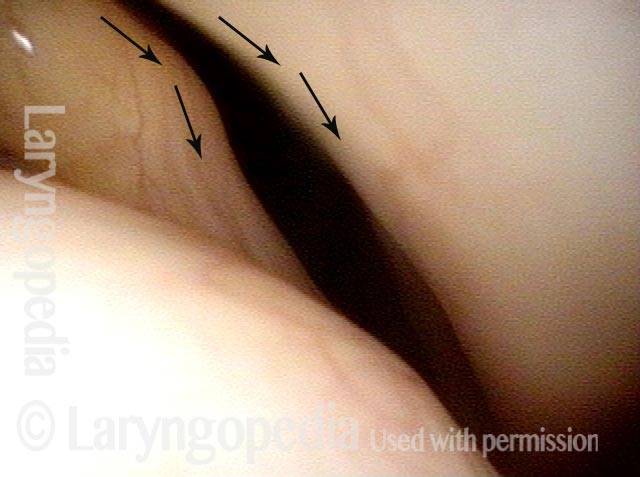

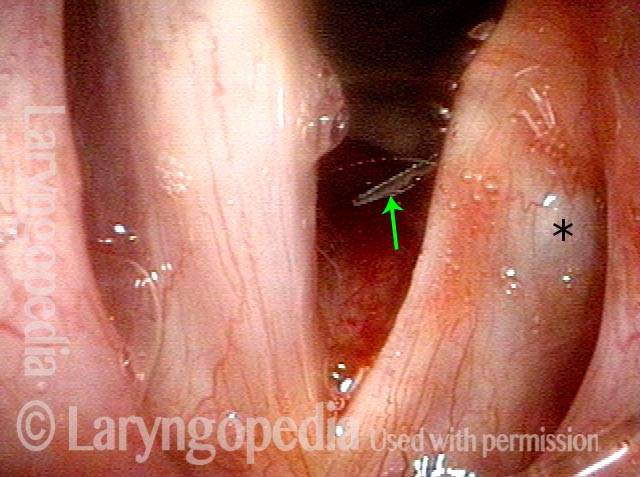

PCA muscle not lateralizing (1 of 3)

PCA muscle not lateralizing (1 of 3)

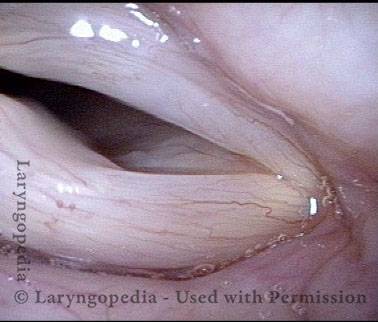

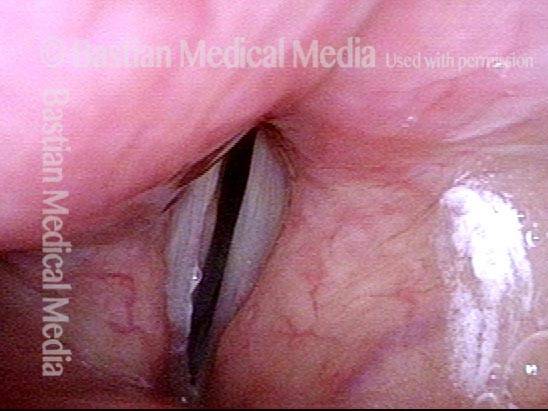

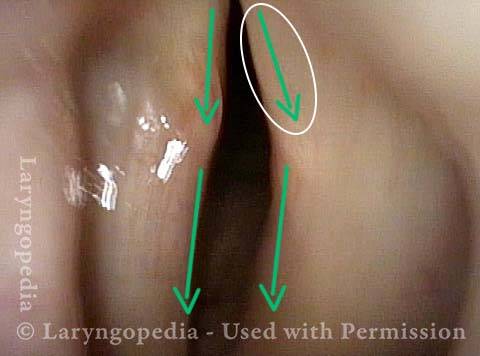

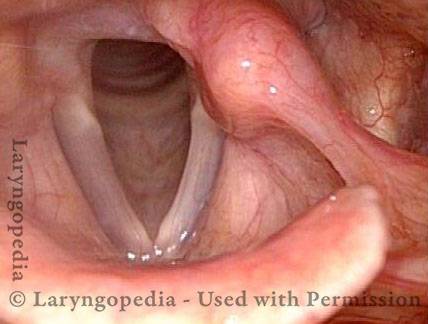

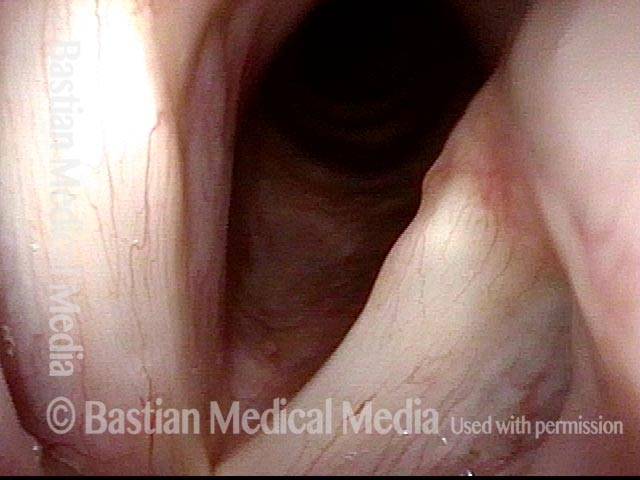

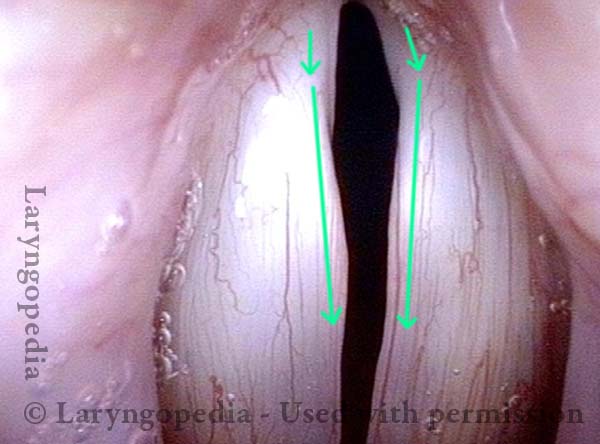

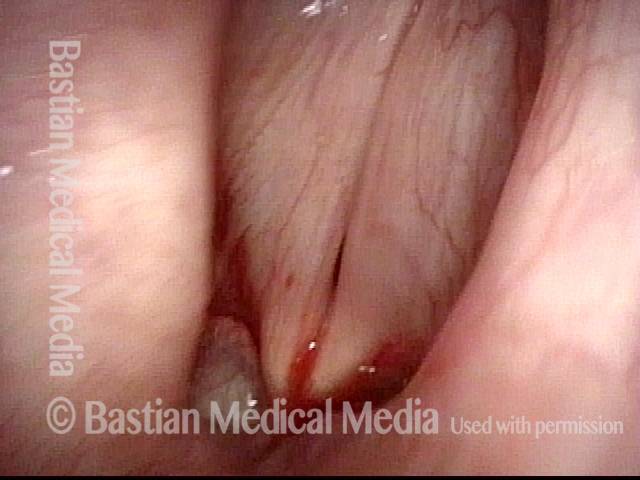

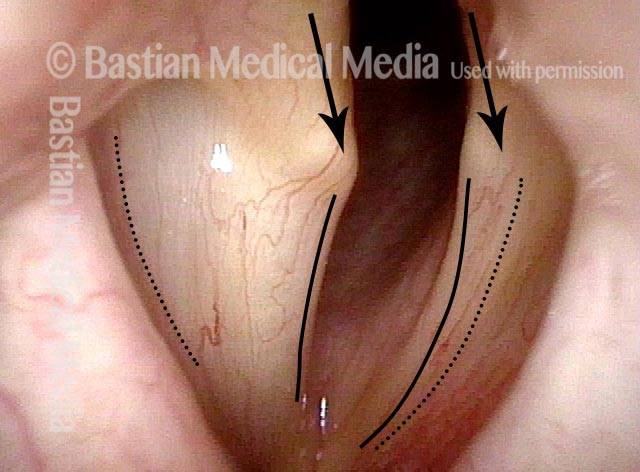

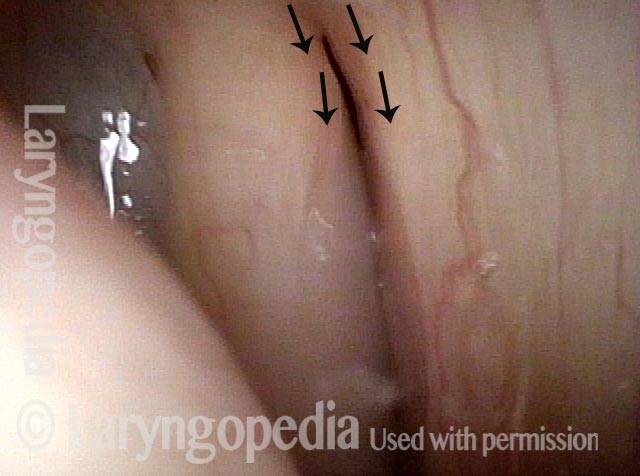

Loss of LCA function (2 of 3)

Loss of LCA function (2 of 3)

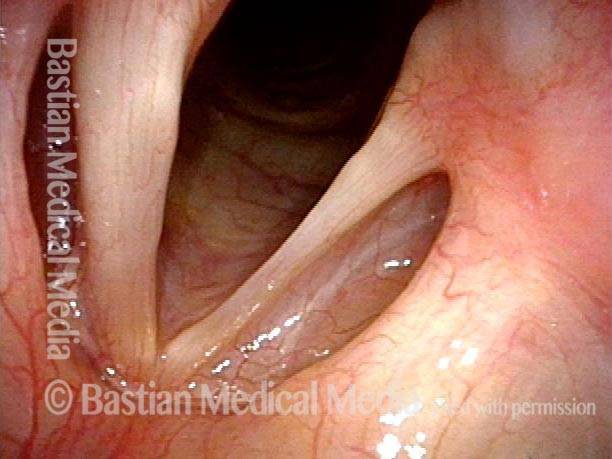

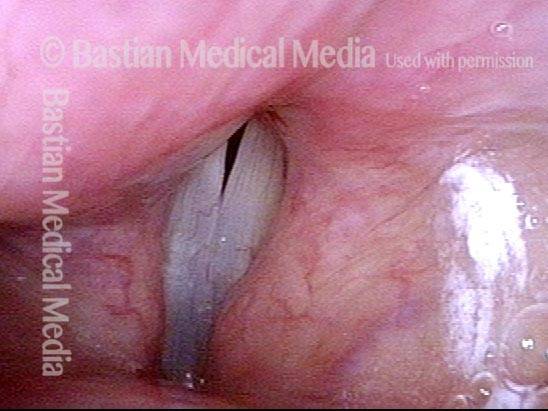

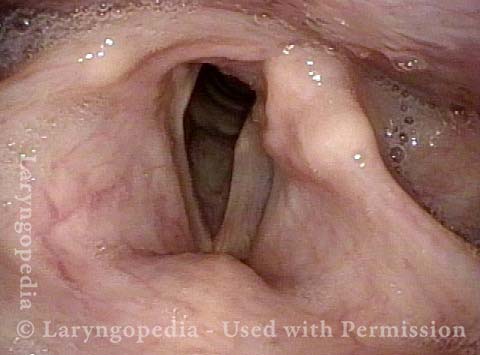

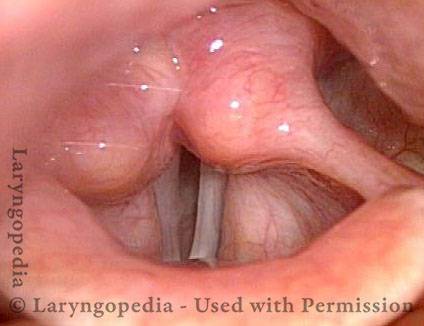

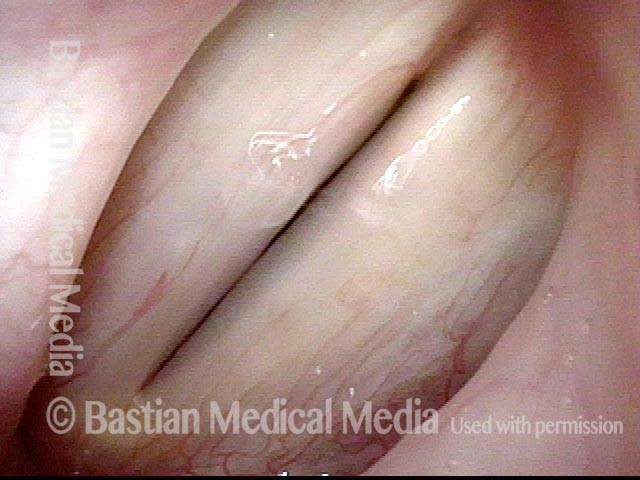

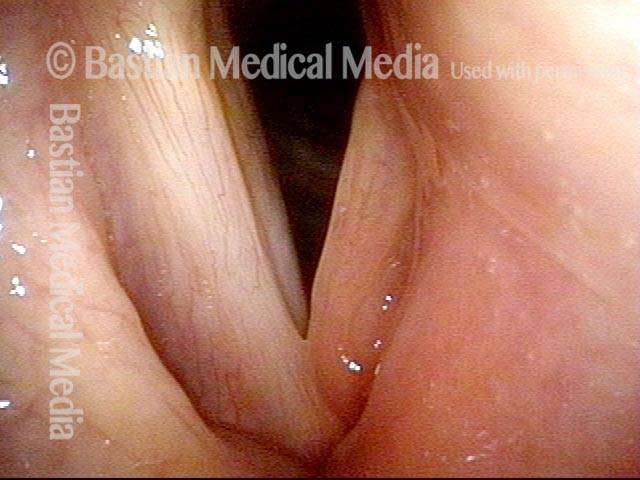

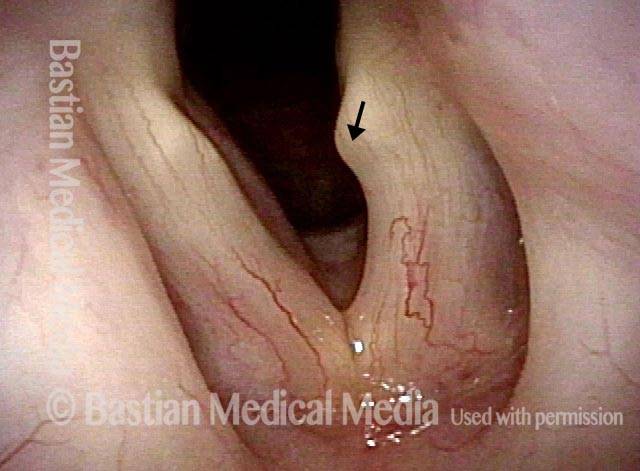

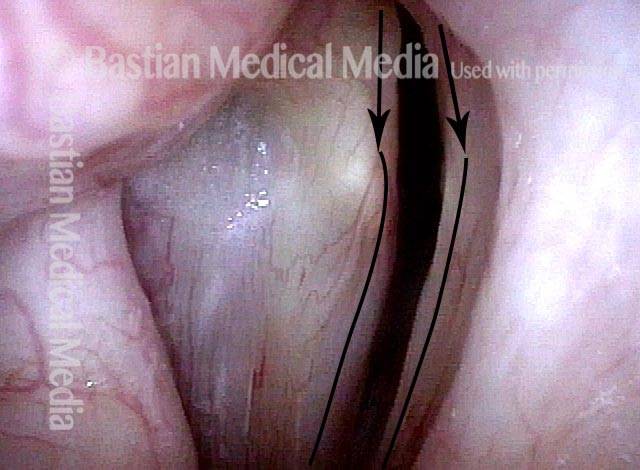

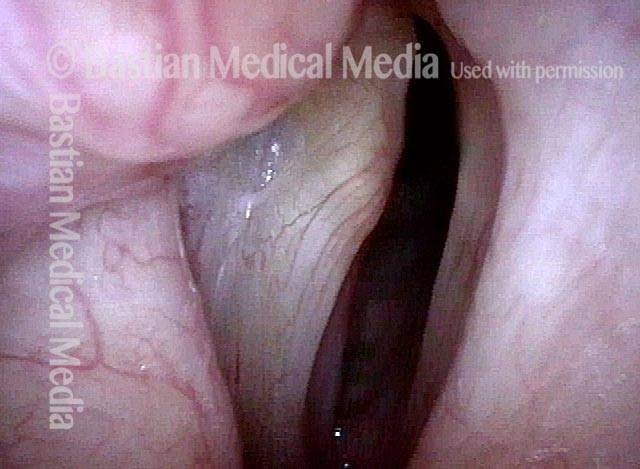

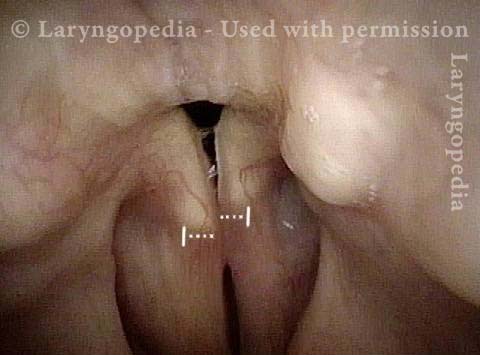

TA denervation (3 of 3)

TA denervation (3 of 3)

Symptoms

One of the most common scenarios is that after investigation the cause is unknown—we call these cases idiopathic. In these cases, a virus is suspected to have played a role.

Two other causes of paresis or paralysis are tumors and trauma. Tumors in these cases could be in the thyroid, lung, esophagus, etc. Trauma is often from surgery that is performed along the path of the vagus nerve, such as for thyroid, spine, lung, or heart problems.

Other symptoms may include:

- Weak, air-wasting dysphonia – The voice may be breathy, weak, double-pitched, or manifest luffing. The person may only be able to say a few words on a breath or be unable to project the voice in noisy places.

- Inability to be heard in noisy locations.

- A tendency of the voice to be somewhat stronger in the morning but to “fade” with use.

- A tendency to cough when drinking thin liquids.

Testing That May Be Done

Laryngeal videostroboscopy

When performed at close range, this examination helps to determine which muscles are affected.

CT scan

This test helps to rule out mass lesions along the course of the nerve. A CT scan is not necessary if the cause is already known (e.g., thyroid surgery).

EMG

This is optional/controversial, and not needed in clinics where a close-range laryngeal videostroboscopy is performed.

Treatment Options

Do nothing

Just accept the symptoms while waiting, especially if recovery is thought to be possible (such as after thyroid surgery with an intact nerve, or after a presumed viral injury).

Vocal exercise with a speech pathologist

Usually helpful if the patient is taciturn. Some patients are mistakenly advised (by well-intentioned family or friends) to rest their voices. Voice rest is in fact counterproductive, except when the general fatigue caused by use of an air-wasting voice makes brief voice rest appropriate.

Voice gel (Injection Laryngoplasty) – an injected implant that is slowly absorbed and therefore temporary

This is not for definitive voice restoration, but can offer a boost while awaiting possible recovery. The aim is for modest or better benefit.

Voice gel implants are often done in-office with topical anesthesia and, occasionally, mild sedation. The gel material—hyaluronic acid—infiltrates the tissue to plump and firm so that the other vocal cord has something to push against.

Duration of benefit is typically four to twelve weeks as the gel slowly absorbs. The hope is that nerve recovery occurs during this time, but injection can be repeated if its benefit fades before it is appropriate to place a permanent implant.

Voice gel + hydroxyapatite — A semi-permanent injected implant

This option is used mostly if the patient does not want a medialization laryngoplasty (option #5 below). If placement of the filler is not ideal, a surgical adjustment might be necessary.

Medialization laryngoplasty with a silastic implant

This is performed in an outpatient operating room under local anesthesia with deep sedation (“twilight”). Surgery requires a horizontal one-inch incision on the front of the neck, and involves placement of a wedge or “shim” to permanently medialize and firm up the paralyzed vocal cord.

There are small risks of bruising and infection. Approximately one out of ten patients needs a second trip to the operating room to adjust the implant.

What to Expect after Medialization?

- Do I need to rest my voice? No. Just use it “prudently” for a few days.

- How long till my voice recovers? The voice will be hoarse for a few days to weeks before it “settles.” In light of this, most patients take a few days to a week off of work.

- How much improvement can I expect? A good result is going from 20% to 70-80%, of normal voice, but this is not guaranteed.

- What if I’m unhappy with my result? Sometimes we wait for further evolution; sometimes we try a few sessions of speech therapy; sometimes we do a revision surgical procedure. This is all according to the patient’s needs and other details.

Do I Need Surgery for Vocal Cord Paralysis?

There is unfortunately not a lot one can do to speed healing. In the photo essay Vocal Cord Paresis Accentuated by Disuse, the patient had sufficient spontaneous recovery to give her an “adequate” voice. The main thing is NOT to rest the voice as this woman did, as all that does is to atrophy any muscle that remains functional. And one can try “voice building” to see if it adds any strength.

If those things don’t work and it is 9 months or more since the onset of the paralysis, the only options are to accept the “new” voice or to proceed to medialization.

Keep in mind that one type of medialization is a simple injection (options #3 & #4), and the other is surgery through a one-inch incision (option #5).

Vocal Cord Paralysis, Before and After Medialization

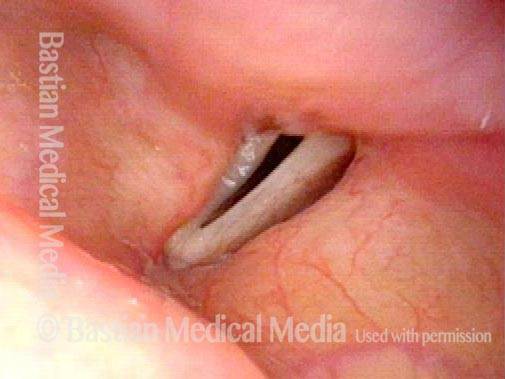

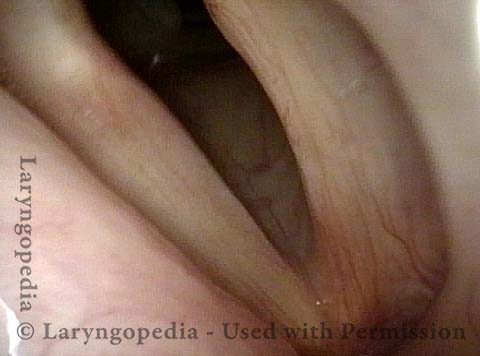

Vocal cord paralysis: before medialization (1 of 12)

Vocal cord paralysis: before medialization (1 of 12)

Vocal cord paralysis: before medialization (2 of 12)

Vocal cord paralysis: before medialization (2 of 12)

Increased amplitude + bowing (3 of 12)

Increased amplitude + bowing (3 of 12)

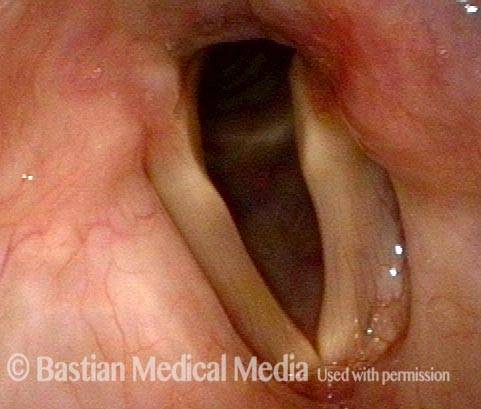

Paralyzed cord cannot close (4 of 12)

Paralyzed cord cannot close (4 of 12)

Visual symptoms are diminished (5 of 12)

Visual symptoms are diminished (5 of 12)

Gap is gone (6 of 12)

Gap is gone (6 of 12)

Similar lateral excursion (7 of 12)

Similar lateral excursion (7 of 12)

Closed phase is improved (8 of 12)

Closed phase is improved (8 of 12)

5 months after medialization (9 of 12)

5 months after medialization (9 of 12)

5 months after medialization (10 of 12)

5 months after medialization (10 of 12)

5 months after medialization (11 of 12)

5 months after medialization (11 of 12)

5 months after medialization (12 of 12)

5 months after medialization (12 of 12)

Evolution of Vocal Cord Paralysis To End as PCA-only Paresis

For some voice doctors, measurement is accorded more respect than observation. Both are legitimate, of course, yet, visual (observational) understanding of paralysis and paresis remains far more useful than EMG, acoustic, or aerodynamic measurements. This case strongly illustrates that point.

This older man underwent thoracic surgery but due to complications was also intubated for much of two days. Immediately upon awakening, his voice was altered. He said it was whisper only.

At his original office visit a month later, he thought his voice had improved to “10%” and examination showed left vocal cord paralysis (TA, LCA, and PCA muscles all non-functional). Three months later, his voice was by his description to 40% and improving further week by week. By month 8 post-surgery, verified at 18 months, he felt his voice was “99%” recovered; examination showed recovery of TA and LCA, but not PCA muscle.

The final diagnosis: Left PCA-only paresis. Rather than being entirely “out,” the PCA seems only to be weak.

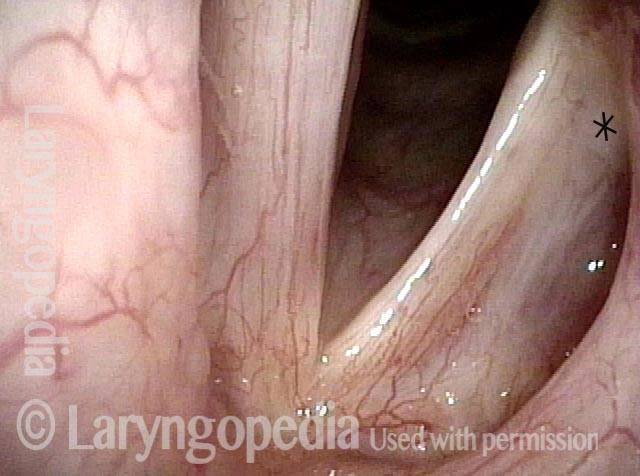

Left Cord Margin Bowing (TA weakness) (1 of 11)

Left Cord Margin Bowing (TA weakness) (1 of 11)

LCA Paresis Identified (2 of 11)

LCA Paresis Identified (2 of 11)

Voice is Breathy! (3 of 11)

Voice is Breathy! (3 of 11)

LCA Paresis Best View (4 of 11)

LCA Paresis Best View (4 of 11)

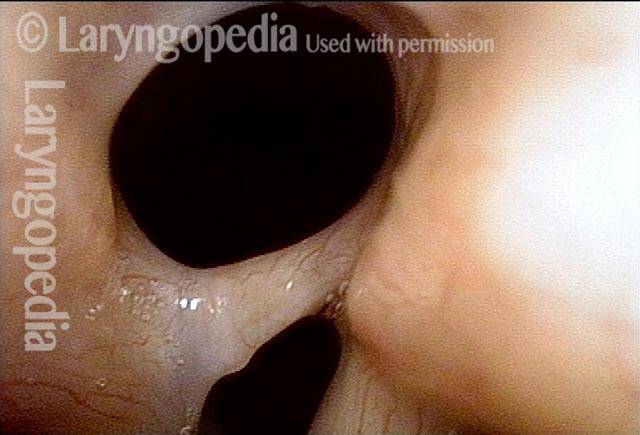

4 Months Later, Glottis Open For Breathing (5 of 11)

4 Months Later, Glottis Open For Breathing (5 of 11)

Gap during phonation less (6 of 11)

Gap during phonation less (6 of 11)

PCA Weakness Is All That remains (7 of 11)

PCA Weakness Is All That remains (7 of 11)

LCA Recovered: The Vocal Process Now Turns Medially (8 of 11)

LCA Recovered: The Vocal Process Now Turns Medially (8 of 11)

At 18M, Left Cord Does Not Abduct Due To Continuing PCA Weakness (9 of 11)

At 18M, Left Cord Does Not Abduct Due To Continuing PCA Weakness (9 of 11)

Left PCA Can Muster Some Lateralization (10 of 11)

Left PCA Can Muster Some Lateralization (10 of 11)

Full Recovery for Voicing, Despite PCA-Only Paresis (11 of 11)

Full Recovery for Voicing, Despite PCA-Only Paresis (11 of 11)

Injection Laryngoplasty with Temporary Gel

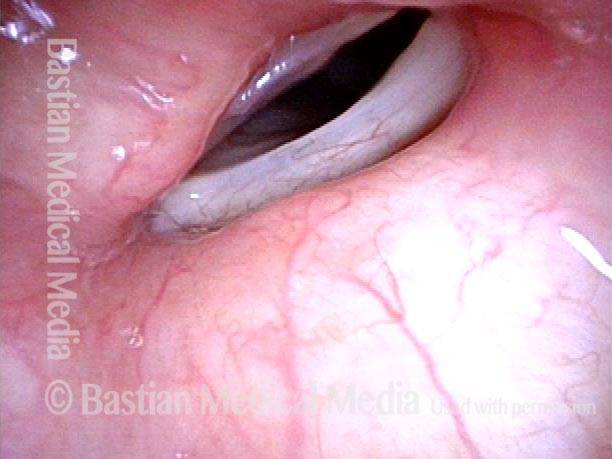

Laryngoplasty (1 of 4)

Laryngoplasty (1 of 4)

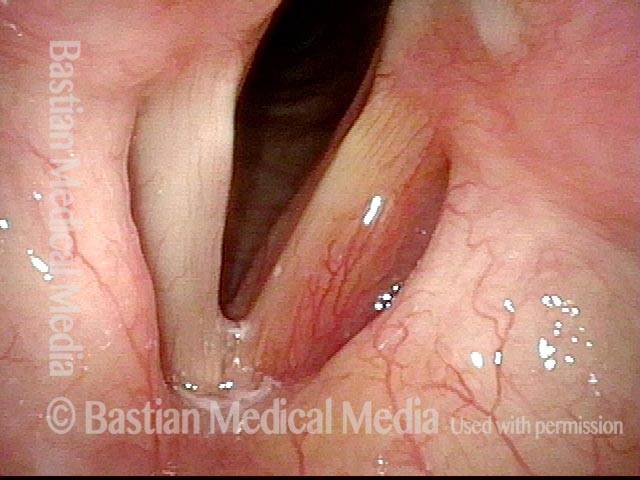

Reason for air-wasting (2 of 4)

Reason for air-wasting (2 of 4)

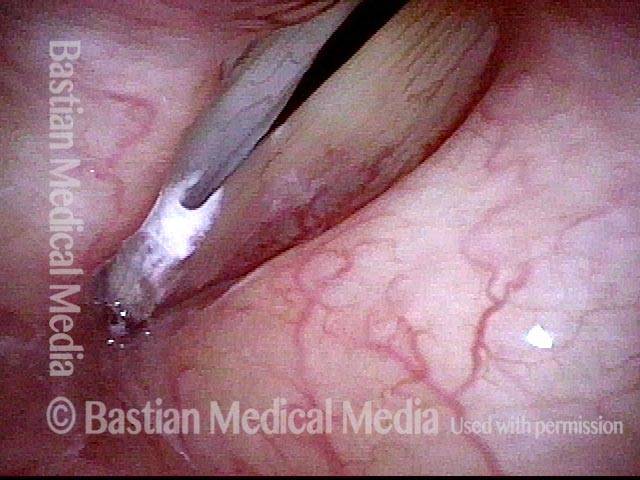

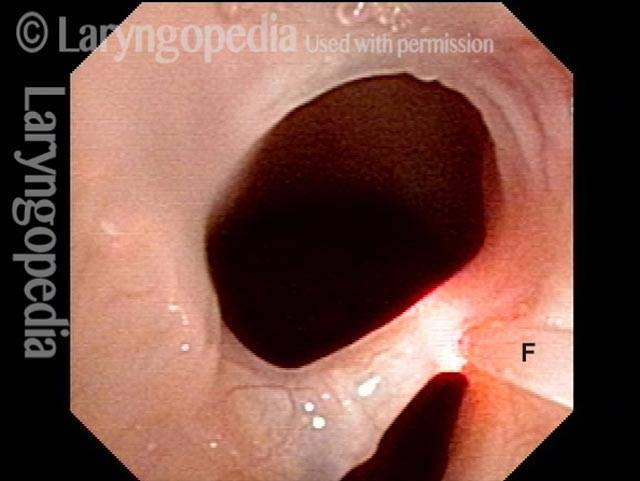

Voice gel injected into vocal cord (3 of 4)

Voice gel injected into vocal cord (3 of 4)

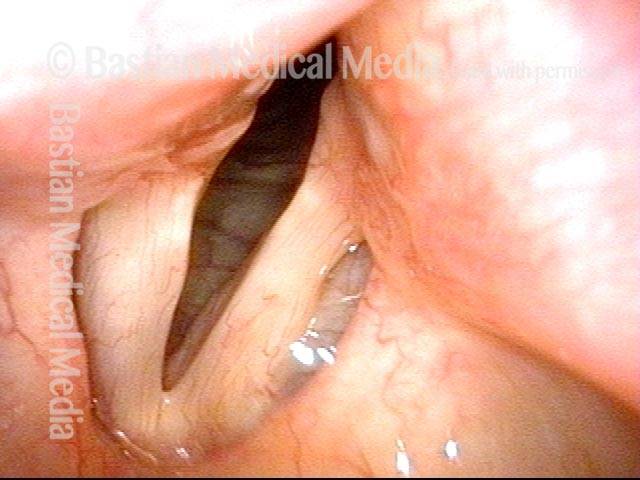

Vocal cords close completely (4 of 4)

Vocal cords close completely (4 of 4)

Vocal Cord Paralysis

Vocal cord paralysis (1 of 2)

Vocal cord paralysis (1 of 2)

Vocal cord paralysis (2 of 2)

Vocal cord paralysis (2 of 2)

Example 2

Vocal cord paralysis (1 of 5)

Vocal cord paralysis (1 of 5)

Phonation (2 of 5)

Phonation (2 of 5)

Closer view (3 of 5)

Closer view (3 of 5)

Evidence of LCA weakness (4 of 5)

Evidence of LCA weakness (4 of 5)

Phonation at very high pitch (5 of 5)

Phonation at very high pitch (5 of 5)

Paralysis, Anterior Branch Recurrent Nerve

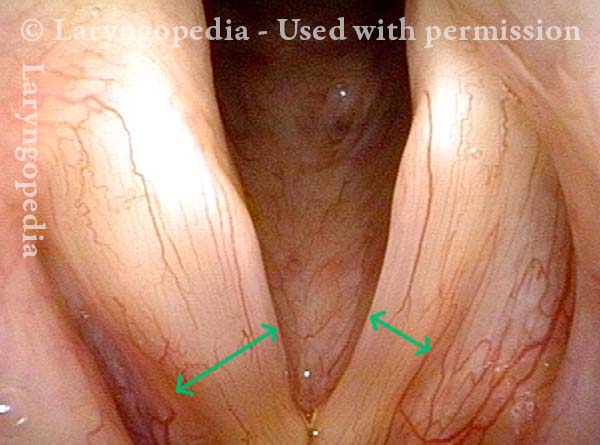

Spaghetti vs linguini folds (1 of 3)

Spaghetti vs linguini folds (1 of 3)

Denervation of TA + LCA (2 of 3)

Denervation of TA + LCA (2 of 3)

Anterior stretch (3 of 3)

Anterior stretch (3 of 3)

Extrusion of Vocal Cord Implant

Inflamed left cord (1 of 3)

Inflamed left cord (1 of 3)

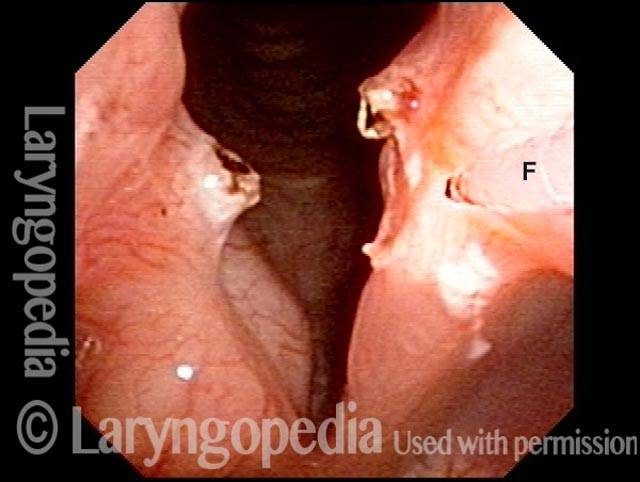

Extrusion of vocal cord implant (2 of 3)

Extrusion of vocal cord implant (2 of 3)

Exposed Implant (3 of 3)

Exposed Implant (3 of 3)

Voice Gel for Immediate Help

Paralysis of left vocal cord (1 of 4)

Paralysis of left vocal cord (1 of 4)

Vocal gel injection (2 of 4)

Vocal gel injection (2 of 4)

Cord closer to midline (3 of 4)

Cord closer to midline (3 of 4)

Complete adduction of cords (4 of 4)

Complete adduction of cords (4 of 4)

TA + PCA-only Paresis

Breathing position (1 of 5)

Breathing position (1 of 5)

Phonatory position (2 of 5)

Phonatory position (2 of 5)

Voice gel injection (3 of 5)

Voice gel injection (3 of 5)

Plumped vocal cord (4 of 5)

Plumped vocal cord (4 of 5)

After voice gel injection (5 of 5)

After voice gel injection (5 of 5)

55 Years of Paralysis with Every Classic Finding

Breathing position, bowed left cord (1 of 4)

Breathing position, bowed left cord (1 of 4)

Approaching voicing position (2 of 4)

Approaching voicing position (2 of 4)

Vocal cord closure, large gap (3 of 4)

Vocal cord closure, large gap (3 of 4)

Open phase of vibration, flaccidity of right cord (4 of 4)

Open phase of vibration, flaccidity of right cord (4 of 4)

Medialization Laryngoplasty Typically Doesn’t Fix the LCA “Finding.”

Left vocal cord paralysis (1 of 4)

Left vocal cord paralysis (1 of 4)

Bowing during phonation (2 of 4)

Bowing during phonation (2 of 4)

After medialization (3 of 4)

After medialization (3 of 4)

Lateral turning remains unchanged (4 of 4)

Lateral turning remains unchanged (4 of 4)

Arytenoid Mismatch Causing Gravelly Voice Quality Is Hard to Fix in Some Cases of Vocal Cord Paralysis

Arytenoids do not align (1 of 5)

Arytenoids do not align (1 of 5)

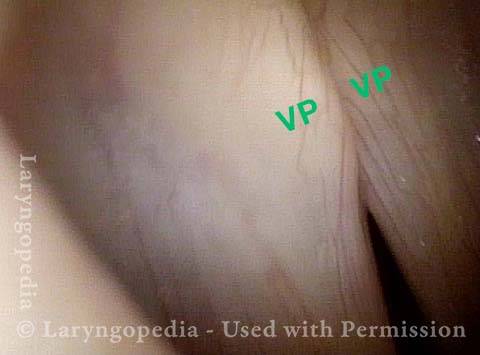

Vocal processes (2 of 5)

Vocal processes (2 of 5)

Vocal processes do not match when touching (3 of 5)

Vocal processes do not match when touching (3 of 5)

Vocal cords out of alignment (4 of 5)

Vocal cords out of alignment (4 of 5)

Asymmetrical vibration (5 of 5)

Asymmetrical vibration (5 of 5)

What is the Solution?

One could medialize more aggressively posteriorly on the left, hoping to raise the level of the cord, but often attempts to compensate for arytenoid mismatch such as that seen here are only modestly successful. Arytenoid superstructure is not useful for assessment of match; instead, the examiner should judge match at the vocal processes.

Voice Gel Injection for Vocal Cord Paralysis

Left vocal cord paralysis (1 of 4)

Left vocal cord paralysis (1 of 4)

Voice-making position (2 of 4)

Voice-making position (2 of 4)

Voice gel injection (3 of 4)

Voice gel injection (3 of 4)

After voice gel injection (4 of 4)

After voice gel injection (4 of 4)

Posterior Commissure Synechiae

Tethered vocal cords (1 of 5)

Tethered vocal cords (1 of 5)

Before laser removal (3 of 5)

Before laser removal (3 of 5)

Immediately after laser (4 of 5)

Immediately after laser (4 of 5)

One month post-op (5 of 5)

One month post-op (5 of 5)

Share this article