Home » Treatment » Treatment: Voice & Other Larynx Disorders » Tracheotomy (Tracheostomy)

Tracheotomy (Tracheostomy)

A tracheotomy is a surgically created passage through the midline of the lower part of the neck into the trachea. That surgical opening is held open by a tracheotomy tube.

The tracheotomy provides a “back door” into the airway, allowing air directly into the trachea and down into the lungs. It may be performed because of a blockage of the upper airway by tumor or other swelling. Or it may be installed in patients who require long-term mechanical ventilation.

If the tracheotomy is no longer needed, the passage / opening usually closes completely after removal of the tracheotomy tube, leaving a scar where it entered the skin.

Tracheotomy vs. Tracheostomy

A similar term—tracheostomy—is used interchangeably with tracheotomy, though technically a tracheostomy should refer to a surgical opening created in a way that makes the opening permanent, and often not requiring a tube to keep the passageway open.

Tracheotomy Care: Mucus Plugs

Why do they occur?

Usually because of:

- Insufficient fluid intake/ Dehydration, causing thick or crusted mucus

- Insufficient use of saline “squirts.”

- Insufficient cleaning of the inner cannula often enough.

- Very low humidity, such as in Winter, in desert climes, or during long airline flights.

How do we respond in general if mucus plugs are tending to occur?

- Hydrate copiously (at least 8 glasses of liquid per day).

- Use the saline squirts regularly and frequently. I usually say “not more than 50 times a day” to make the point that one can use many of these.

- Use a bedside humidifier in the Winter, when it is very cold outside, IF the saline squirts are not worlking well enough.

- Remove and clean the inner cannula more frequently to “stay ahead” of the mucus.

How do we respond if there is a sudden (unexpected) mucus plug that is partial-just causing noisy breathing but no anxiety?

- Cough a series of times.

- Squirt some saline, and cough again (20 seconds or so).

- Squirt again, and cough again (20 seconds or so).

- Repeat 2 and 3 as many times as desired.

- If you don ‘t produce the mucus and the noisy breathing continues, remove the inner cannula, run tap water through it and if that dislodged the plug, then replace the inner cannula.

- If you can’t simply dislodge with running water, proceed to hydrogen peroxide and brush, rinse, and replace.

What if there is a sudden, nearly complete blockage of the trach tube?

- Remove the inner cannula.

- If that resolves the problem, run tap water through it and if that dislodged the plug, replace the inner cannula.

- If you can’t simply dislodge with running water, proceed to hydrogen peroxide and brush, rinse, and replace.

Hands-Free Tracheoesophageal Voice

After laryngectomy, most people prefer to glue a small voice button over the stoma that they push when they wish to speak. When not pushed, the button springs up and allows air into the trachea.

This person is instead using a hands-free valve. He can initiate voice by beginning each sentence with a little “kick” of exhaled air that closes a flexible diaphragm and diverts pulmonary air through the TEP device and into the pharyngoesophageal segment.

Tracheal Deformity After Tracheotomy

This man had a grave and life-threatening illness that required mechanical ventilation in an ICU for about 3 months. The initial weeks were through an oro-tracheal tube (a tube placed through the mouth, between the vocal cords, and into the trachea); the remaining 2 ½ months were via a tracheotomy (breathing tube inserted through the base of the neck directly into the trachea).

Now out of hospital for many months, he has a barking cough, and occasionally mild harsh inspiratory noise.

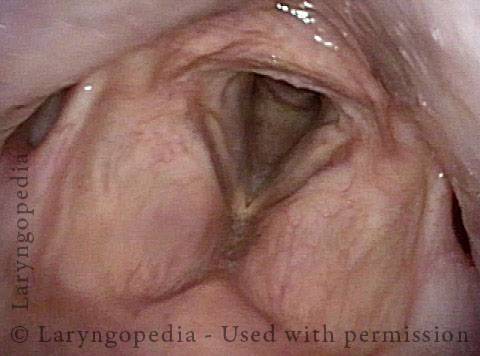

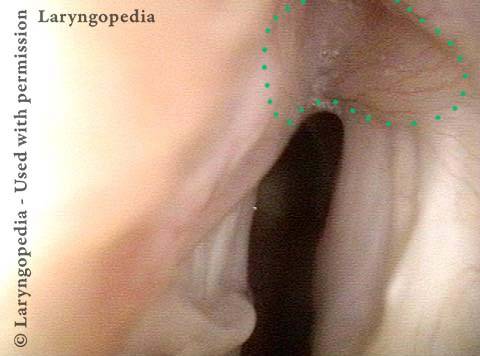

No breathing tube damage on the vocal cords (1 of 5)

No breathing tube damage on the vocal cords (1 of 5)

Airway is narrowed below vocal cords (2 of 5)

Airway is narrowed below vocal cords (2 of 5)

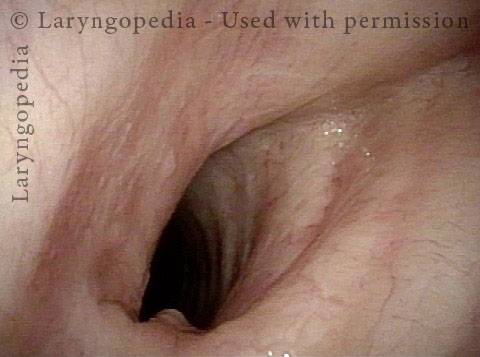

Deformed airway (3 of 5)

Deformed airway (3 of 5)

distinctly narrowed but not marginal airway (4 of 5)

distinctly narrowed but not marginal airway (4 of 5)

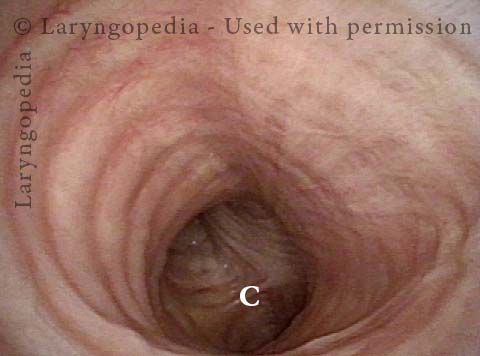

Carina is normal (5 of 5)

Carina is normal (5 of 5)

Nuances of Endotracheal Tube Injury

This woman with high-risk comorbidities of diabetes and obesity, was in ventilated in ICU more than a month for pulmonary complications of Covid-19 infection. She had an orotracheal tube in place for 3.5 weeks, and then a tracheotomy tube was placed.

Now at her first visit a year later, she remains tracheotomy-dependent, and is told she has bilateral vocal cord paralysis (disproven in the following photo series).

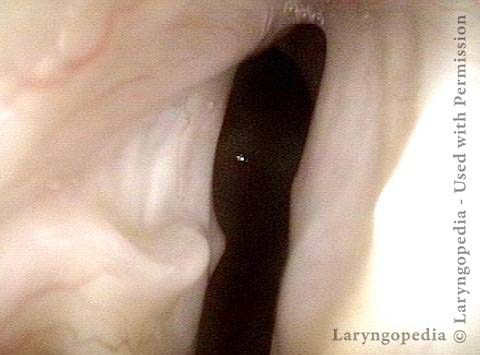

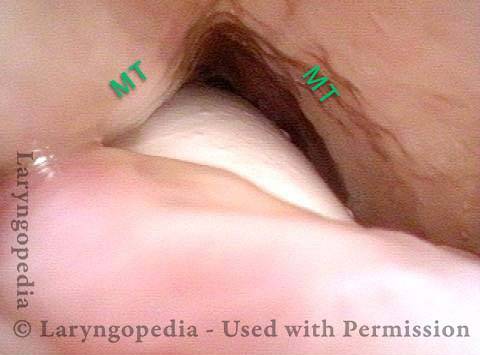

Maximum glottic opening (1 of 8)

Maximum glottic opening (1 of 8)

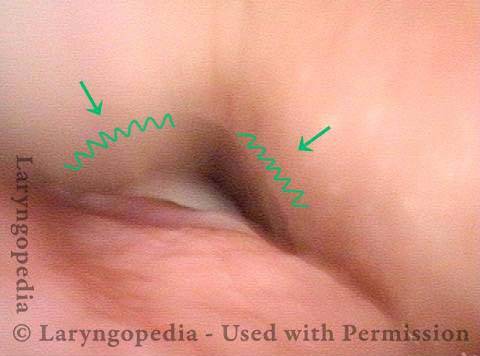

Undersurface mucosa indraws (2 of 8)

Undersurface mucosa indraws (2 of 8)

Phonation (3 of 8)

Phonation (3 of 8)

Posterior commissure divot (4 of 8)

Posterior commissure divot (4 of 8)

Further evidence of scarring (5 of 8)

Further evidence of scarring (5 of 8)

View into trachea (6 of 8)

View into trachea (6 of 8)

Vibration of trachea (7 of 8)

Vibration of trachea (7 of 8)

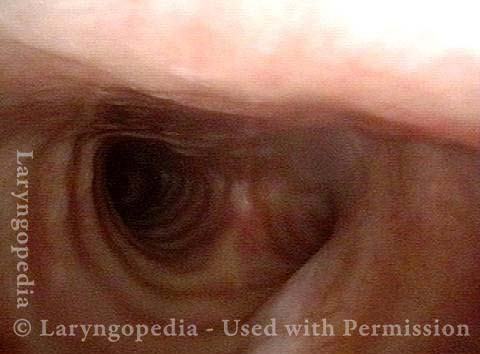

Open trachea beyond the tube (8 of 8)

Open trachea beyond the tube (8 of 8)

The plan here is posterior commissuroplasty, followed by placement of a smaller trach tube and a trial of plugging. If plugging is tolerated during the day, she will need a sleep study with it plugged at night, given the tracheomalacia and her obesity.

A Fenestrated Tracheotomy Tube allows Voicing when there Is Stenosis

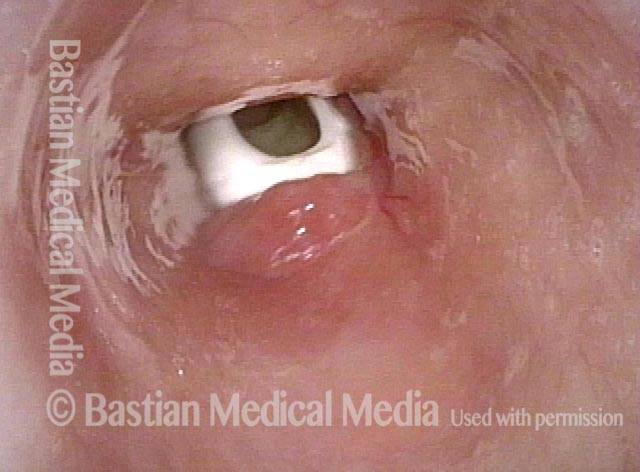

Tracheotomy (1 of 4)

Tracheotomy (1 of 4)

View below vocal cords (2 of 4)

View below vocal cords (2 of 4)

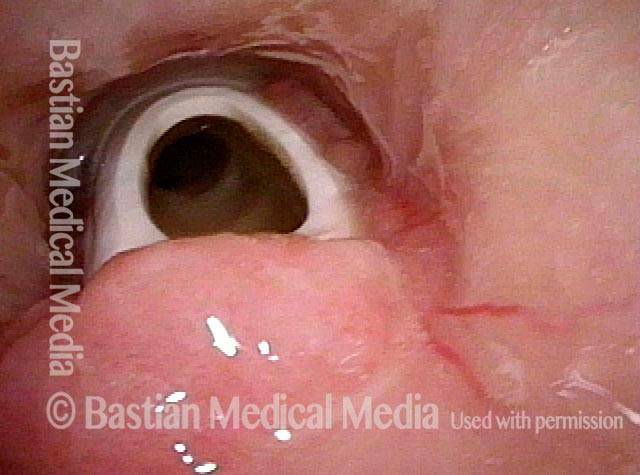

Fenestra (3 of 4)

Fenestra (3 of 4)

Patient post-trach (4 of 4)

Patient post-trach (4 of 4)

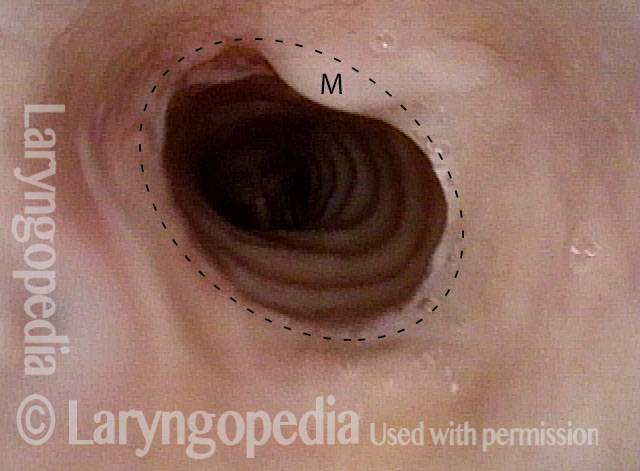

Trachea, with Tracheotomy Tube

Trachea, with tracheotomy tube (1 of 2)

Trachea, with tracheotomy tube (1 of 2)

Trachea, with tracheotomy tube (2 of 2)

Trachea, with tracheotomy tube (2 of 2)

Share this article