Glottic Stenosis or Scarring

Glottic stenosis refers to scarring in the larynx at the level of the vocal cords (glottis). It usually narrows the space available between the cords for inflow of air to the lungs while breathing. Or it can cause divots in the posterior vocal cords.

What Causes Glottic Stenosis?

Congenital Web

A baby can be born with vocal cords fused together due to a developmental defect.

Endotracheal (Breathing) Tube Injury

Breathing tubes go through the mouth, down into the larynx, between the vocal cords and into the upper trachea. If a person requires ventilation due to critical illness and the breathing tube sits between the vocal cords for several weeks, then raw surfaces can be created. A scar between the raw surfaces on opposite cords can bind the vocal cords together with insufficient remaining space for easy breathing. Or there can be scarring (ankylosis) of the cricoarytenoid joints.

Radiation for Larynx Cancer

When larynx cancer is radiated for cure, occasionally the radiation burns are deep enough to create scarring between the cords, or to progressively fibrose (stiffen) the cricoarytenoid joints. Other causes are gunshot wounds, or swallowed plumber’s lye injury (usually young children).

Symptoms

Persons with glottic stenosis describe exercise intolerance and/ or noisy inspiratory breathing (causing involuntary inspiratory phonation or stridor) if the scarring is only the posterior vocal cords (cartilaginous glottis). Or if there is scarring of the anterior 2/3 of the cords (membranous glottis), voice will also be affected.

Treatment

Treatment options include microsurgical release of scar tissue, with or without steroid injection and topical anti-scarring agents, and occasionally an open reconstruction with grafting.

Breathing Tube Injury, not Vocal Cord Paralysis

This middle-aged woman was injured severely in an auto accident as a teenager. Recovery involved a long stay in ICU, and ventilation via a breathing (endotracheal) tube for a few weeks prior to tracheotomy. Fifteen years earlier, a posterior commissuroplasty was done by me on the left side.

Severely short of breath before that procedure, she said the improvement was such that she was able to do most activities of daily living remarkably well for many years.

While still much better than prior to the posterior commissuroplasty, she has felt a little more limited in the past few years and wants now another similar airway-widening procedure. Speaking voice can easily pass for normal, though she thinks it is occasionally a little rough.

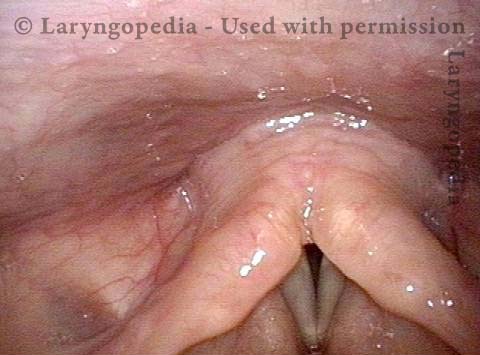

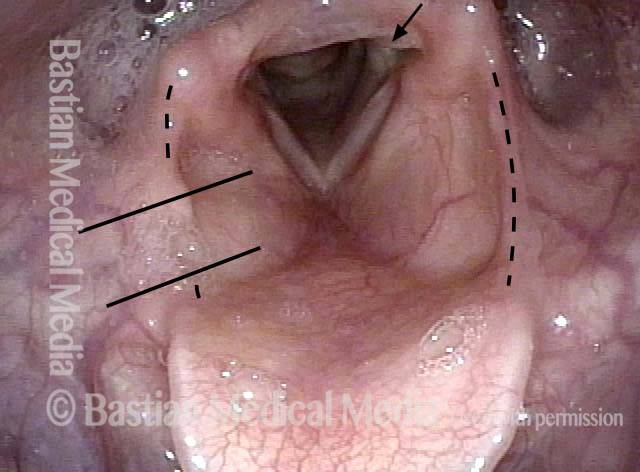

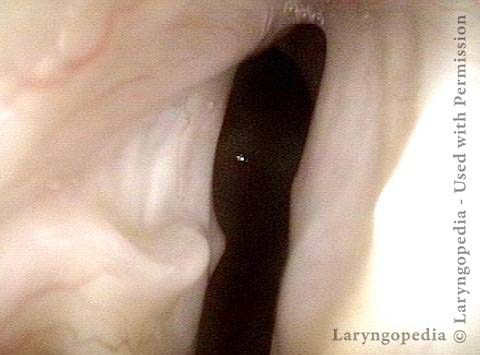

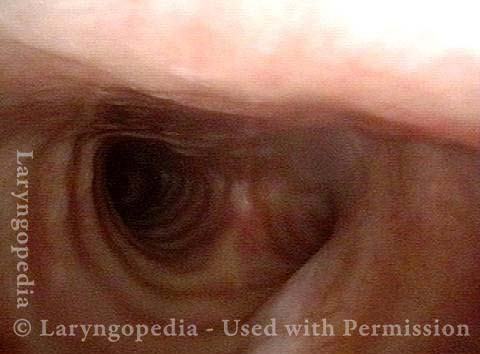

Aperture is very narrow (1 of 6)

Aperture is very narrow (1 of 6)

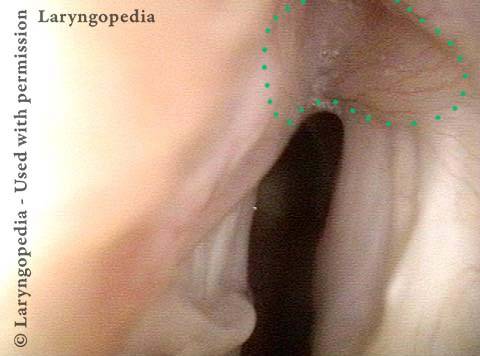

Involuntary inspiratory phonation (2 of 6)

Involuntary inspiratory phonation (2 of 6)

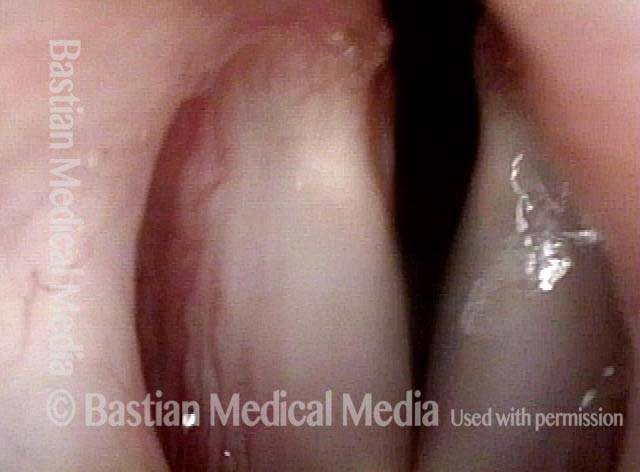

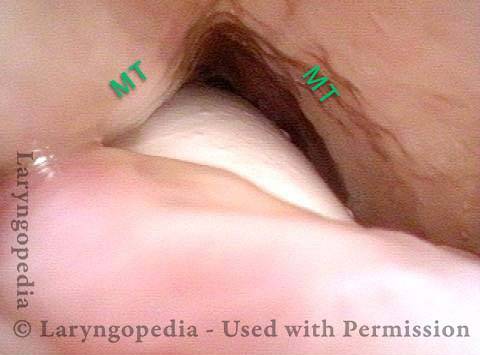

Divot on left vocal cord (3 of 6)

Divot on left vocal cord (3 of 6)

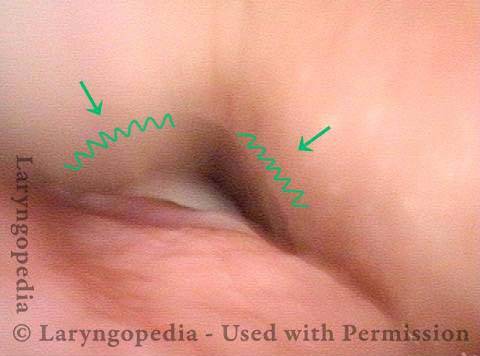

Endotracheal tube injury (4 of 6)

Endotracheal tube injury (4 of 6)

Laser cookie bite (5 of 6)

Laser cookie bite (5 of 6)

Surface scarring in the tracheotomy (6 of 6)

Surface scarring in the tracheotomy (6 of 6)

Supraglottic, Glottic, and Subglottic Endotracheal Tube Injury

Breathing tube injury (1 of 4)

Breathing tube injury (1 of 4)

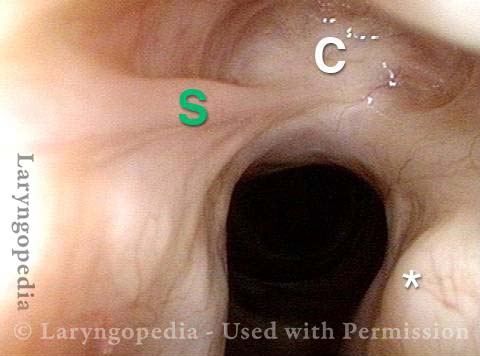

Aryepiglottic cord defect (2 of 4)

Aryepiglottic cord defect (2 of 4)

Phonation (3 of 4)

Phonation (3 of 4)

Posterior subglottic thickening (4 of 4)

Posterior subglottic thickening (4 of 4)

Nuances of Endotracheal Tube Injury

This woman with high-risk comorbidities of diabetes and obesity, was in ventilated in ICU more than a month for pulmonary complications of Covid-19 infection. She had an orotracheal tube in place for 3.5 weeks, and then a tracheotomy tube was placed. Now at her first visit a year later, she remains tracheotomy-dependent, and is told she has bilateral vocal cord paralysis (disproven in the following photo series).

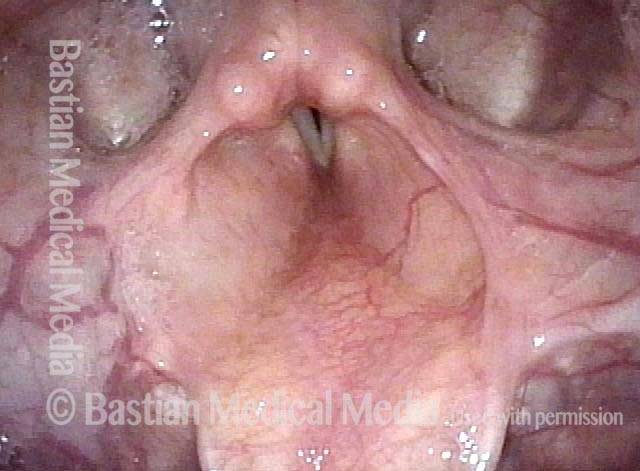

Maximum glottic opening (1 of 8)

Maximum glottic opening (1 of 8)

Undersurface mucosa indraws (2 of 8)

Undersurface mucosa indraws (2 of 8)

Phonation (3 of 8)

Phonation (3 of 8)

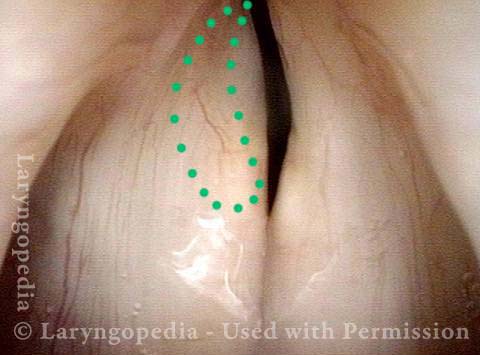

Posterior commissure divot (4 of 8)

Posterior commissure divot (4 of 8)

Further evidence of scarring (5 of 8)

Further evidence of scarring (5 of 8)

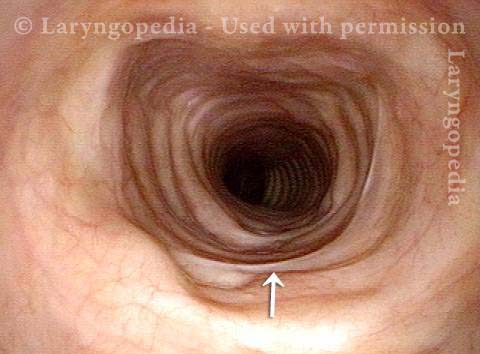

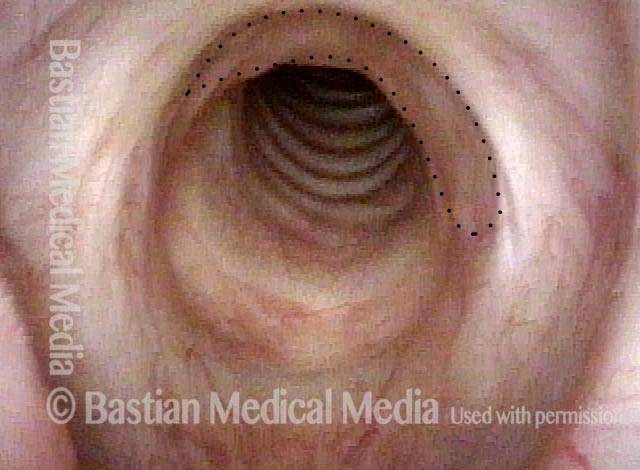

View into trachea (6 of 8)

View into trachea (6 of 8)

Vibration of trachea (7 of 8)

Vibration of trachea (7 of 8)

Open trachea beyond the tube (8 of 8)

Open trachea beyond the tube (8 of 8)

The plan here is posterior commissuroplasty, followed by placement of a smaller trach tube and a trial of plugging. If plugging is tolerated during the day, she will need a sleep study with it plugged at night, given the tracheomalacia and her obesity.

Share this article